Repairing Melbourne through active citizenship

This article was written as a response to the events MTalks: ‘Repairing the City: Green Urban Interventions and Positive Futures’ (listen above), ‘MAL Syllabus Discussions: Liveability Through Design’ and ‘MAL Syllabus Discussions: Design Heritage and Violence,’ held at MPavilion 2022 (January–April 2022).

In Melbourne, we got through six lockdowns totalling 262 days between March 2020 and October 2021. The pandemic left us estranged from the city. After such a period of enforced stasis, how can we reconnect with one another? How can we connect with our city, where existing wounds were only further exposed by the pandemic? From a lack of housing affordability to a tenuous connection to place and the ubiquity of the climate crisis, the impetus to connect – to do more –has never felt more pertinent. As the pragmatics of navigating connection during a pandemic – when isolation became a civic duty – slowly drift from reality to memory, now is the time to ask ourselves what we can do to act as constructive and positive agents of the city.

The outcome of the 2022 Australian federal election speaks to an impetus for change. Toeing the line of an almost-hung parliament, the wave of ‘Teal’ independents and the success of the Greens signifies constituents’ disenfranchisement with the major parties. Australians have made a clear call for change, for genuine climate action, and for a more localised politics of inclusion. It’s an exciting time, and we can continue to make change beyond the ballot box, to hold our governments to account and enable a more complex and inclusive urban space.

This is where active citizenship is necessary. It is integral to a healthy system of engagement between constituents and government that citizens are able to organise themselves, mobilise collective resources, and both protect and implement the common good. Organising and mobilising are effective ways for citizens to become power-holders within the system, and act as agents in creating place.

The past can inform our present

Urban activism operates at differing scales and towards differing ends, though it can be hard to identify a starting point for engagement. When addressing the dizzying immensity of material extractivism associated with the built environment industries, landscape architect Jane Hutton describes the importance of centring solidarity and reciprocity. Cities are intricate spaces with deep, multifaceted histories; citizen action to improve the city requires solidarity through connections and learnings between disciplines and movements. Efforts to shape the city across these complexities have a large pool of precedents in urban active citizenship globally, but also locally in Melbourne. It is through these examples that the myth of Australian political apathy is exposed, and that the validity and success of doing can be felt.

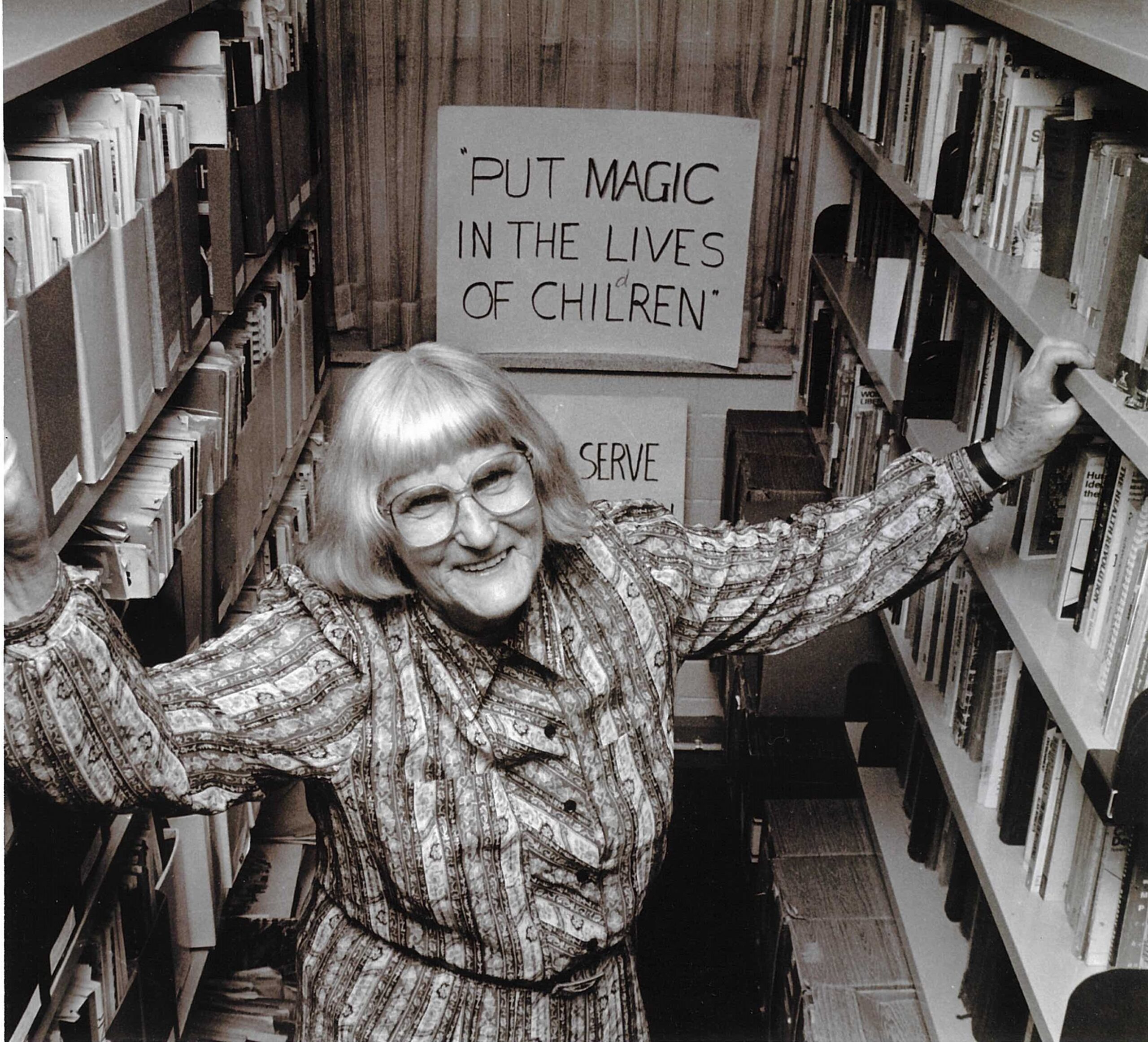

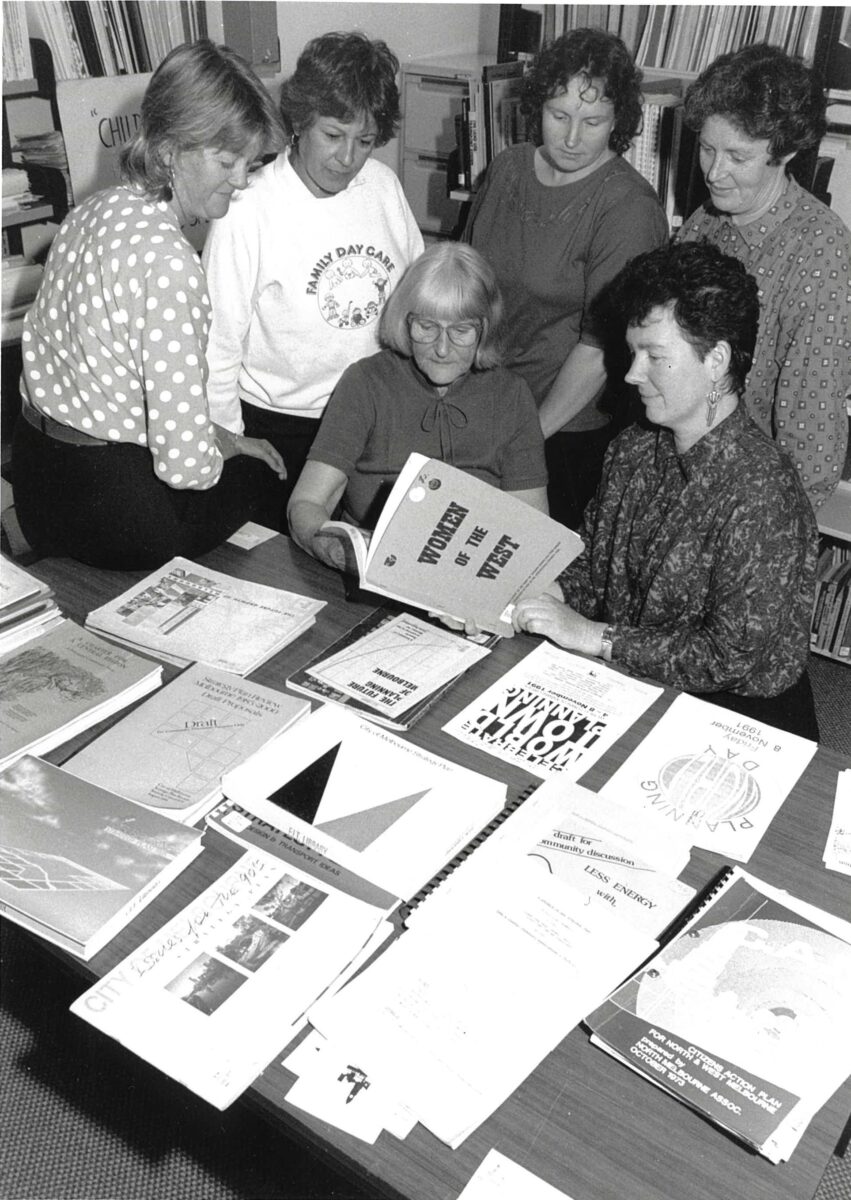

From the 20th century, we have the example of Ruth and Maurie Crow. The Crows were activists operating in the intersecting spheres of politics and the built environment from the 1930s to the 1990s. Their engagement with Melbourne’s urban communities was nothing short of prolific: they were involved in protests against Nazism, the establishment of mothers’ groups and childcare initiatives (in the 1940s!), campaigns for communal public amenities, progressive planning schemes for the city, and publishing hundreds of articles in the speculative planning journal Irregular (later Ecoso Exchange), which discussed issues facing urban populations. Ruth Crow was a particularly key figure in developing Melbourne’s tradition of localised activism, and centring women as participatory figures in that development. In the true spirit of capacity building through shared knowledge, Ruth donated her and Maurie’s collection of personal papers to Victoria University, establishing a resource for future movements in active citizenship.

Cyclist advocacy has been an element of Melbourne’s urban history since at least the 1970s, with the founding of the Bicycle Institute of Victoria (now the Bicycle Network), and later the Bicycle User Groups (BUGs) that formed in the 1990s. Such groups are responsible for safe bike lanes in the city today, and they continue to push for the expansion of bike lanes in the urban landscape. They also promote greater bike safety through the reporting of unsafe drivers and those who park in bike lanes, despite councils stalling on promises to take action on these issues.

In 2018, Federation Square was saved from a corporate takeover by the efforts of Citizens for Melbourne and the ‘Our City, Our Square’ campaign. Arguing against the privatisation of the civic heart of Melbourne through the partial demolition of the square for a flagship Apple store, the campaign successfully led to the redesign and, later, scrapping of the plan due to a review from the heritage council.

Understanding and acknowledging this history enables future efforts in citizen action. Mobilising, rallying and organising can be highly effective; it has worked in the past, and we should consider how we can use this practice to shape the city into the future.

What’s more, we must work towards undoing the colony’s deliberate obfuscation of First Nations histories within urban spaces. Everyday commemorations can help to remind and centre the existence of Indigenous Australia within the city’s physical and cultural landscape. As a public, engaging with these commemorations and seeking to understand our city as Country is a shared responsibility. In Places of Reconciliation: Commemorating Indigenous History in the Heart of Melbourne, historian Sarah Pinto discusses the importance of ‘commemorations’ in helping a wider audience to see the city as Country, and disrupting the dominance of colonial narratives written into the landscape. However, as argued by senior Wurundjeri elder Aunty Joy Murphy Wandin AO, we need to continue to build the capacity of Indigenous peoples to be involved in the decision-making processes that govern and construct our built environments.

Shifting sensibilities

It is uplifting to see the success of past efforts in urban transformation, though there is still much to be done. We must reach beyond the isolating pit of cynicism and helplessness that can prevent us from harnessing the collective impetus for change to form tangible action. Reach out to people, ask questions, have discussions, and find a way of being an active citizen. Play to your strengths and invest in your interests.

For me, it has been engaging with organisations such as Melbourne Art Library and the Centre for Multicultural Youth, as well as participating in programs such as MPavilion’s M_Curators, which has allowed me to connect with others and change the way I see the city and the world. As I navigate an early career in the inherently extractive field of architecture, I take heart from a quote by London-based architect and academic Jeremy Till: “To live in the Anthropocene… needs a shift in sensibility from humans as distanced beings in the pursuit of freedom and progress to humans embedded in, and responsible for, a non-human world of interconnected systems.” This idea of civic responsibility transcends any single discipline; it foregrounds the imperative to exist in reciprocity with environment – and to connect with others.

Lily Di Sciascio was part of the annual M_Curators program, an initiative for 16–25-year-olds interested in design and arts programming developed by MPavilion, an architecture and design commission built in the Queen Victoria Gardens in Melbourne each summer. This initiative was made possible by MPavilion’s presenting partner Bloomberg Philanthropies.

Woody Shmith, who co-curated the ‘Repairing the City’ event, was essential in helping Lily Di Sciascio to develop this article.