Repairing Australia’s affordable housing crisis

Over the past four decades, Australian public policy has shifted its focus from one kind of housing support to another. The transition from social housing to rent assistance raises profound questions about the role of government in the economy, about conceptions of fairness and efficiency, and about the relative weight placed on the value of personal choice and personal security. In the face of different policy approaches by both state and federal governments, Peter Mares looks at how we’ve made the housing crisis much worse – and how we could make it better.

State and federal governments have two main ways to help vulnerable Australians to find a home. The first approach is to supply subsidised rental accommodation through what is called social housing, which includes both public housing provided by state governments and community housing provided by not-for-profits. The second approach supplements tenants’ incomes to help them afford to pay rent in the private market through Commonwealth Rent Assistance.

There are arguments for and against both approaches, but in shifting from one to the other since the 1980s, we’ve ended up doing both badly, therefore, worsening housing insecurity for Australians on the lowest rungs of the income ladder and pushing them deeper into poverty.

Immediately after World War Two, Australia invested heavily in social housing – or public housing, as it was known then – with state authorities such as the Victorian Housing Commission and the South Australian Housing Trust constructing and managing subsidised homes, with funding provided by the Commonwealth. This was formalised through the first 10-year Commonwealth–State Housing Agreement (CSHA) enacted by the Labor government of Ben Chifley (1945–49) and renewed in subsequent decades by Liberal prime ministers. Economist Saul Eslake calculates that Canberra funded the states to build more than 15,000 new dwellings annually from the mid-1950s to the mid-1970s, and more than 12,000 new dwellings annually from the mid-1970s to the early 1990s.

Over time, though, with the shift from a pro-government-intervention Keynesian approach to market-based economics, the dominant view of government’s role in housing changed and the federal government has shied away from directly funding social housing. Since the 1990s, the construction of new dwellings has flatlined, with the exception of a blip when the Rudd government built 20,000 new homes under its brief but successful social housing initiative in response to the global financial crisis.

Now, the vast bulk of federal government spending on housing goes to boosting household incomes to help people rent in the private market. Today, the amount the Commonwealth spends on rent assistance is more than triple the sum it commits to the states under the latest version of the CSHA, the National Housing and Homelessness Agreement.

From social housing to rent assistance: a prediction from the past

In 1998, a prescient research paper by the Parliamentary Library warned that a shift from building social housing to paying rent assistance could lead to our current situation: hundreds of thousands of poorer households falling between the two stools of inadequate supply of social housing on the one hand, and insufficient levels of rent assistance on the other. The paper raised four major concerns, all of which have come to pass.

How should the federal government best respond to this slow-moving crisis? Should it revert to the postwar practice of funding states and territories to build social housing, or should it boost rent assistance so vulnerable tenants can afford to rent in the private market?

First, it warned that Australia might suffer severe shortages of affordable rental housing for low-income tenants – not just those reliant on government payments, such as pensions, but also low-paid workers. It noted that proponents of switching funding from public housing to rent assistance assumed that there was sufficient housing in the private market to meet demand, and that if demand increased, the market would respond by increasing supply. Drawing on developments in the UK, the US and Germany, the author warned that this was a flawed assumption: “The overseas experience suggests that increased rent assistance payments and reductions in the provision of public or social housing have not, by themselves, triggered sufficient increased provision by the private sector.”

Almost a quarter of a century later, the experience is clear in Australia too – the switch from social housing to rent assistance has not been matched by an increase in the supply of affordable private rentals for low-income households, as is evident from annual surveys such as Anglicare’s Rental Affordability Snapshot – a review of about 75,000 rental listings around the nation – and the Rental Affordability Index compiled by SGS Economics and Planning.

This marks a fundamental difference between the two approaches to housing support: postwar-style direct government investment automatically increases the supply of affordable homes for low-income tenants, while rent assistance does not.

The Parliamentary Library’s second fear was that rent assistance, which is indexed to the consumer price index, would not keep pace with rising rents, and that low-income renters would end up under ever greater financial strain as they struggled to keep a roof over their heads – exactly what has happened. The Treasury’s Retirement Income Review concluded that the “value of Commonwealth Rent Assistance has not kept pace with market rents, especially for low-income renters.” It calculated that while the maximum rent assistance payment rose by about 55 percent between 2001 and 2019, rents for low-income earners more than doubled over the same period.

Third, the research paper noted that people earning low wages (without dependent children) are not eligible for Commonwealth Rent Assistance, even if they are forced to pay high rents. While this was less of an issue in the 1990s, the author foresaw that “a marked change in the relationship between the level of wages and rents in Australia” could land them in difficulties. Again, the author was farsighted: rents have gone up while wages have stagnated, generating rental stress not only for people who receive government benefits, but also for ineligible low-paid workers in sectors such as aged care, childcare, hospitality, cleaning and retail.

A fourth concern was that the shift away from building dwellings to supporting rents would lead to a blowout in waiting times for social housing as the allocation of places was triaged to ensure that they went to those in greatest need. The report warned that this would in turn concentrate disadvantage in social housing, with negative social consequences. This has fostered the (often unwarranted) stigmatisation of social housing, unfairly undermining its reputation as a public good and fuelling neighbourhood objections that make it harder to get new social housing projects off the ground.

One thing the Parliamentary library did not explicitly foresee was that escalating real estate prices would compound the problem by thwarting aspirations for home ownership. As higher-income earners are pushed into renting, they muscle out poorer tenants in the competition for cheap housing. Tenants with less money are forced to accept the lowest quality dwellings or relocate to suburbs with the cheapest rent, which are often the most remote from jobs and services.

The data doesn’t lie

According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, on 30 June 2020 there were 166,000 households on social housing waiting lists around Australia, with almost four in ten of those households classified as being in ‘greatest need’. This category includes people who are already homeless or at risk of homelessness, including women and children fleeing family violence, as well as people living in housing that is making them sick, or that no longer meets their needs.

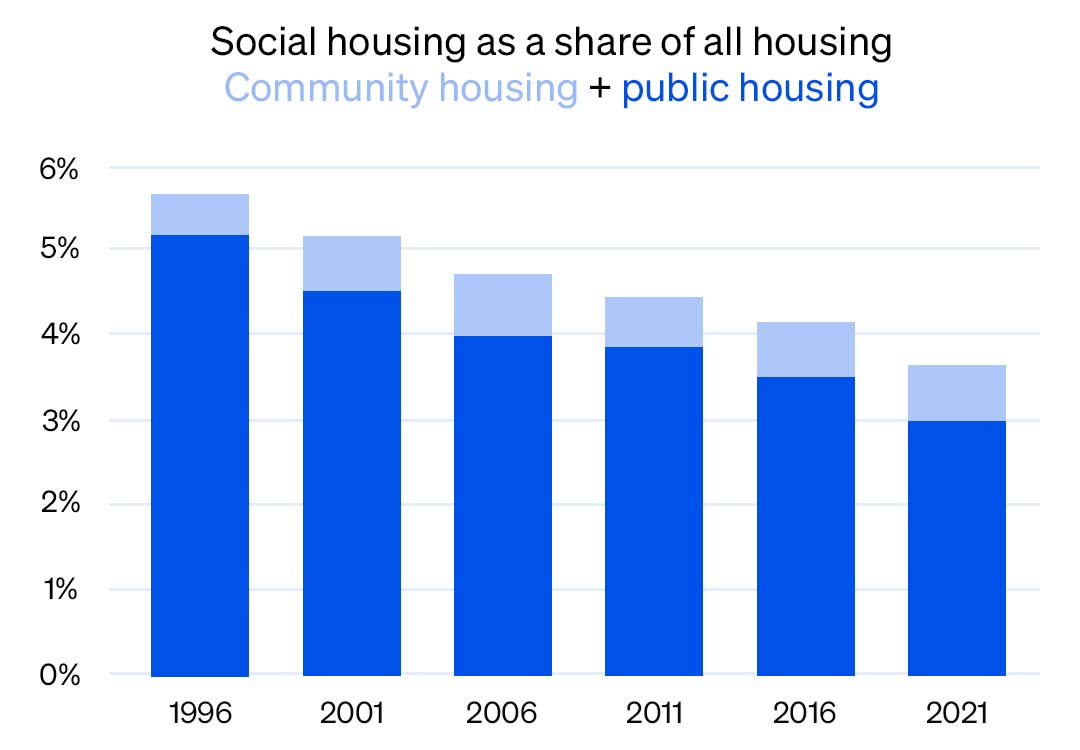

As the chart below shows, in 1996 social housing (comprising both state-run public housing and not-for-profit community housing) accounted for more than six percent of all housing in Australia. By 2016 that share has fallen to less than four percent – and when data from the most recent census is released in June 2022, it may well be closer to three percent.

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-08-12/fact-check-social-housing-lowest-level/11403298

Accompanying table: https://public.tableau.com/views/socialhousing/censusdash

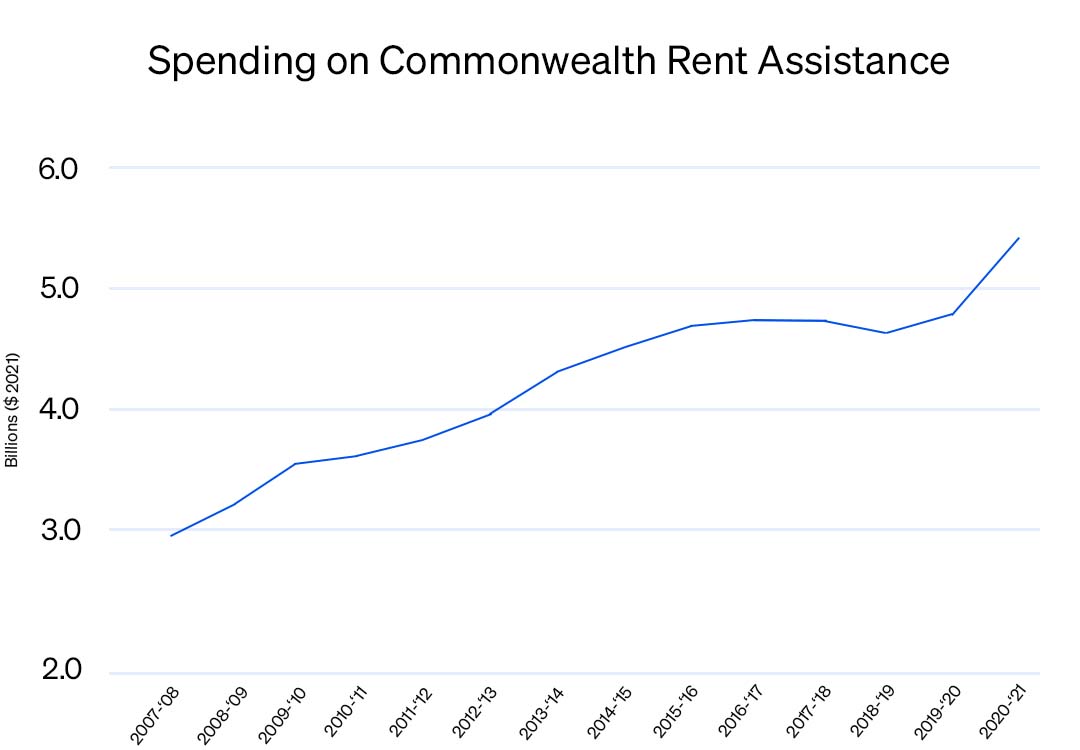

On the flip side, spending on Commonwealth Rent Assistance has risen sharply, from just under $3 billion in 2007–08 to more than $5.3 billion in 2020–21 – an increase of around 80 percent in real terms. This reflects the growing tide of tenants struggling to pay their rent in the private market. The number of ‘income units’ (a rough proxy for households) receiving rent assistance has grown from around fewer than one million to more than 1.6 million.

Yet rent assistance is tightly capped – the maximum weekly payment is just $73 – and inadequate indexing means that the support paid to tenants has not kept pace with rising rents. So, despite the growing cost of Commonwealth Rent Assistance to the public purse, rental stress is on the rise, too.

Rental stress occurs when rent eats up more than 30 percent of a household’s already low income, pushing tenants into poverty and forcing them to scrimp on other essentials such as food, heating and medical care. Twenty years ago, about one third of households remained in stress after qualifying for Commonwealth Rent Assistance; last year, the share was closer to half (46 percent). Even with federal government support, almost 750,000 tenants are paying more rent than they can afford and around 280,000 households are still shelling out more than half of their income in rent.

Admittedly, without rent assistance, far more households would be in stress, but clearly both support systems – social housing and Commonwealth Rent Assistance – are failing vulnerable households.

What is more, the interaction of these two inadequately funded systems results in serious inequities, with some people receiving far greater housing support than others, regardless of their level of need and vulnerability.

A hypothetical case study

A hypothetical example illustrates the problem. Let’s compare the situation of two ‘Lauras’ — Laura A and Laura B — who both receive the age pension and both live alone in an equivalent one-bedroom unit. The difference between them is that Laura A rents in the private market, and Laura B lives in social housing.

Laura A qualifies for the maximum level of rent assistance, which tops up her pension to a total weekly total of $567. After paying $300 a week in rent – more than half of her income – Laura A is left in severe rental stress with just $38 per day to cover all her other essentials.

Because Laura B lives in social housing, her rent is capped at 30 percent of her income to prevent her from falling into rental stress. So, although her unit would cost $300 in the private market, Laura B only pays $148 per week in rent and has $49 a day left for other expenses.1

As well as having extra money to spend, Laura B will enjoy much greater security of tenure. She has no cause to fear, like Laura A, that she may be forced to search for a new home at any time because the landlord decides to end her lease or jack up her rent.

As the comparison between the two Lauras makes clear, from a tenant’s point of view, social housing looks far preferable to rent assistance.

But this depends on there being enough social housing for people who need it to live in. Since there is not, we end up with a serious injustice. Laura A, who gets rent assistance, receives a housing subsidy of $73 a week, while Laura B, who lives in social housing, receives a subsidy of $152 a week (the gap between the $148 she pays in rent and her unit’s market price).

Postwar-style direct government investment automatically increases the supply of affordable homes for low-income tenants, while rent assistance does not.

As the Productivity Commission comments: “The system is fundamentally inequitable – the financial assistance a household receives depends on the sector from which they rent their home, rather than their circumstances.” Benefits flow disproportionately – and arbitrarily – to the incumbents of social housing, even if tenants struggling in the private market require more urgent help.

Freedom to choose, security to stay

This situation poses a question: how should the federal government best respond to this slow-moving crisis? Should it revert to the postwar practice of funding states and territories to build social housing, or should it boost rent assistance so vulnerable tenants can afford to rent in the private market?

In a 2016 report on Reforming Human Services, the Productivity Commission argued for the latter with its central rationale being increased personal choice: rent assistance gives tenants the freedom to select their preferred housing type and location, whereas social housing is more likely to be allocated according to availability. Yet as things stand, for tenants on the lowest incomes, this ‘choice’ is largely illusory. According to Anglicare’s 2021 Rental Affordability Snapshot, people who rely on the pension can afford just 0.5 percent of available properties. For those who receive JobSeeker or Youth Allowance, the share of affordable rental homes is zero. What is more, ‘choice’ in the private rental market can be undermined by other factors such as discrimination in letting practices.

If Commonwealth Rental Assistance was to provide meaningful choice to low-income tenants in the private market, it would need to be dramatically increased, perhaps even to a level comparable to the implicit subsidy in social housing (which may inadvertently inflate private rents). In addition, we would need national reform to rental laws, going further than those implemented in Victoria, and perhaps taking inspiration from the German system, to give tenants much greater rights, particularly around security of tenure.

Housing in the too-hard basket

The Coalition government’s general approach to housing is to push the problem back onto the states and territories. The messaging from Michael Sukkar, Minister for Housing, Homelessness and Social and Community Housing, is that “primary responsibility” for housing lies with the states and territories. Yet, apart from planning and zoning, the federal government controls most of the levers that impact the demand for housing and its affordability, including immigration levels, tax settings and the rate of government payments such as the age pension, JobSeeker and rent assistance.

This leaves the states to go it alone on social housing. The Victorian Government’s $5.3 billion Big Housing Build aims to complete 12,000 dwellings in four years and boost Victoria’s stock of social housing by 10 percent. Other states have announced smaller programs, but it’s nowhere near enough to address the national shortfall of more than 430,000 rental homes for Australians on very low incomes.

If we are serious about housing justice in Australia, the debate should not be about building more social housing or increasing rent assistance – we need to do both, and history shows that we can. Housing was a central plank of Australia’s reconstruction program after World War Two; it can play an equivalent role in helping us to recover from COVID-19.

- These calculations assume that both Laura A and Laura B receive the full pension and all supplements which is $987.60 per fortnight. It assumes that Laura B lives in public housing and is therefore ineligible for rent assistance. The equation would be the same if Laura B lived in community housing, since in that case the entire value of her rent assistance would go to the housing provider, leaving her situation unchanged.