The Nicholas Building makes the case for artist spaces

It is fair to say that Melbourne is the Australian city most associated with the arts – a Berlin of the southern hemisphere, replete with DJs, printmakers, dance troupes and street artists. Historically overlooked, the draw of ‘creative industries’ is now well known to elected officials. There are numerous government organisations and well-funded not-for-profits whose mission is to support the arts in Victoria; their activities run the gamut from promoting haute culture, such as the opera and ballet, to presenting work by First Nations artists and even facilitating legal street art in laneways. But there are also blind spots. Lots of money is set aside for venues that exhibit new works while comparatively little is doled out to help subsidise the spaces where these works are created.

Some factors that help make an art scene successful are intangible. It is a ‘feeling in the air’, according to the cliché used to describe everything from St Kilda in the 1980s to fin-de-siècle Paris. One concrete factor is the need for cheap ‘raw’ space. In Melbourne, studios are available at some highly coveted locations run by local councils and arts organisations, but most are supplied by the private market, often in light industrial and formerly industrial areas. These are also the urban-fringe spaces that are now being redeveloped for apartment complexes and transportation infrastructure, leading to a squeeze for space.

It is not just studio space that artists need to make work but a whole constellation of associated goods and services: lighting rentals, welders, fabricators and sound studios. These small businesses thrive in proximity to artists and makers but are often under-considered by the policymakers who help steward the capital-A ‘Arts’ sector in cities.

While there are new spaces being developed with creatives in mind, such as Collingwood Yards, many new builds can be prohibitively expensive for emerging artists, with annual rates that exceed $400 per square metre. These spaces are not always built with slop sinks and industrial ventilation, meaning that tenants are more likely to be graphic designers, architects and animators than painters and sculptors. Larger and messier creative practices are often pushed from one peripheral zone to another. It is not uncommon for artists of a certain age to have started their careers in the very centre of Melbourne, when it was still undergoing a process of deindustrialisation and urban renewal, only to shift half a dozen times to locations further out on metropolitan lines as their rent leapt up. In recent years, some have left the city altogether in search of cheap barns and former factories in rural Victoria.

A space that caters only to a narrow range of makers won’t produce the interesting collaborations that might happen when a calligrapher and milliner share space, or when an installation artist works above a neon sign studio.

One well-known holdout in the very centre of Melbourne’s CBD is the Nicholas Building, an 11-storey Greek Revival stone fortress a block from Flinders Street Station. Owned by the same four families for the last 49 years, it is currently on the market, and the ‘vertical village’ of artists and craftspeople fear that a sale could bring in new owners eager to convert the structure into a hotel or luxury housing.

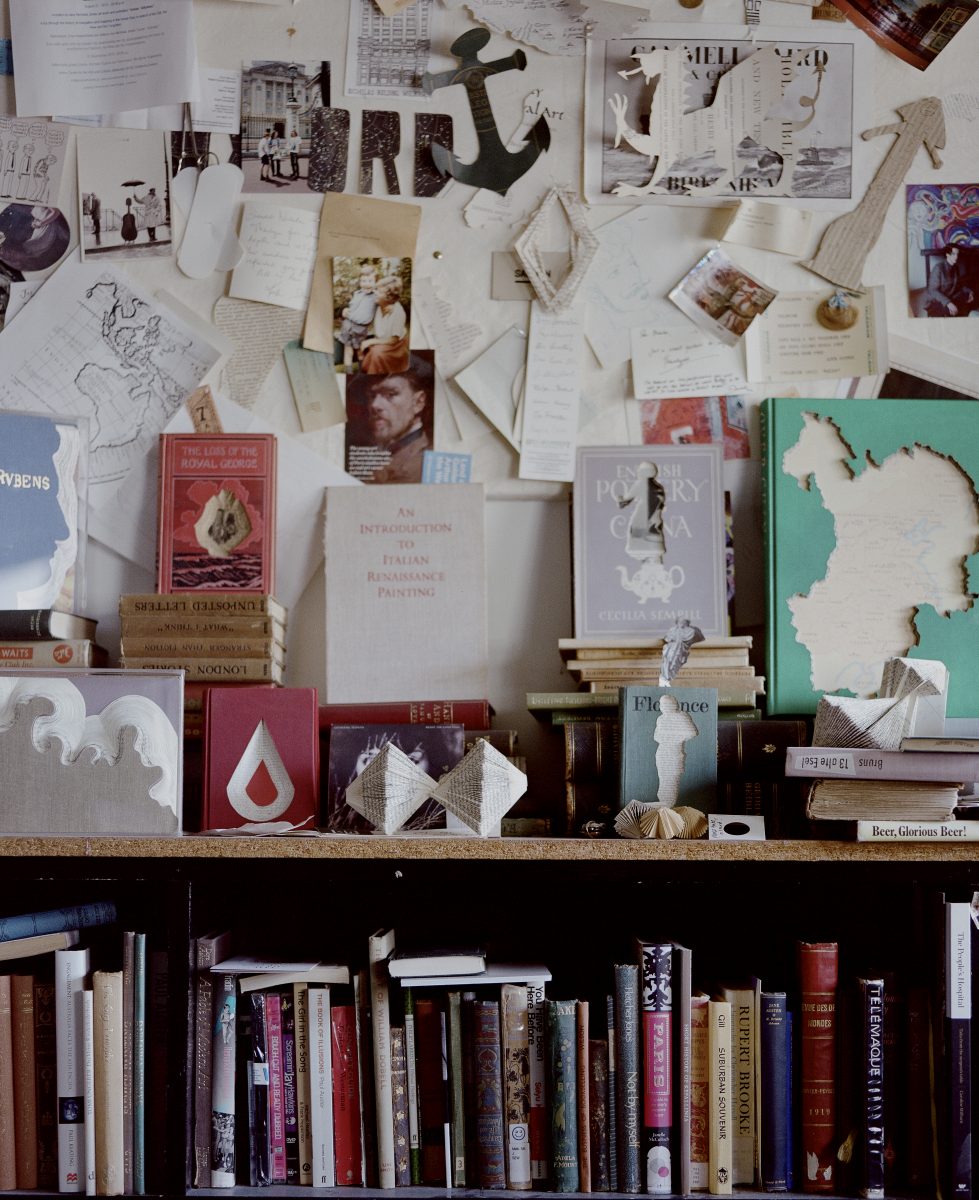

Critical to the Nicholas Building’s longevity as a creative space is that it mixes art studios, galleries and artisanal ateliers with small-scale entrepreneurs. Its hallways are lined with snug spaces that are affordable for fibre artists, milliners and more. There is no slick reception area, and the building’s stairwells and old-timey elevators open directly onto the city. The interiors are old and a bit worn but character-filled – the leadlight-glass arcades and tiled wainscotting evoke a bygone Melbourne, and there are signs of the many notable Melburnians who have passed through these spaces: a 1997 photograph shows artist Vali Myers squatting on the carpeted floor of her seventh-floor studio, her works leaned against the walls, with the striped-brick facades of Flinders Lane visible through the windows. It is a place that, according to Dario Vacirca, the co-director of the tenant-driven Nicholas Building Association that formed in the building in 2017, allows for creators to be “autonomous with the option of collectivity… It’s a self-started creative ecology that’s evolved over decades.” What’s clear from even a short conversation with those advocating for the preservation of the building as an artist space is that the environment of places such as the Nicholas Building is achieved through a long process of fermentation; it’s not something that can be picked up and moved or reproduced elsewhere.

When looking to artist spaces, it is difficult to avoid biological and environmental illusions. These are communities that take root, grow and blossom, but they can also stagnate and wither as funding dries up, or when the surrounding climate becomes inhospitable. Diversity within these ecosystems is also crucial – not just in terms of the cultural background of artists, but also their age and practice. A space that caters only to a narrow range of makers won’t produce the interesting collaborations that might happen when a calligrapher and milliner share space, or when an installation artist works above a neon sign studio.

Innovation lore morphed into one of the most popular strains of folk history during the 20th century. Management studies and business programs often make reference to the innovation-fostering properties of certain postwar scientific research spaces, notably Bell Labs – the massive New Jersey compound whose arterial hallway made for serendipitous encounters – and Xerox PARC – a campus in Palo Alto, California where, free from the prying gaze of higher-ups (across the country in Rochester, New York), employees flirted with Bay Area countercultural currents and thought up novel inventions such as the mouse, bitmap graphics and the laser printer. Yet, there has been too little attention paid to the ways that structures and sites have helped to catalyse creative processes, with ‘arts’ seen as something that can be added towards the end of a development process, almost as an overlay.

For years, a ‘just add art’ ethos has reigned, manifesting itself in public art (see, for example, the ‘plop art’ sculptures installed in many newly developed areas) and the radical pruning of more holistic arts funding schemes. Many critics see this as an instrumentalisation of culture that came in with the Creative City movement. The movement’s origins lie in Melbourne where, in the late 1980s, David Yencken argued for “an emotionally satisfying city… that stimulates creativity among its citizens.” But, by the turn of the millennium, Yencken’s appeal for a city that is nuanced and stimulating had given way to Richard Florida’s The Rise of the Creative Class, a book that included a ‘creativity index’ (and guaranteed its author an income stream as he crisscrossed the world consulting mayors on how to move up in the rankings).

Cultural workers have taken issue with Florida’s brand of place marketing, advocating instead for the retention and shoring up of local arts districts, the neighbourhood-level clusters that are, in many ways, the polar opposite of the capital intensive, architecture-driven arts precincts promoted as ‘job creators’ and ‘tourism drivers’. In New York City, some advocates have taken to calling these ground-up arts areas Naturally Occurring Cultural Districts (NOCDs). The name is inspired by the equally clunky acronym NORC (Naturally Occurring Retirement Community), locales where seniors have chosen to ‘age in place’, and often acting as magnets for geriatric services, a move that inverts the logic of the purpose-built retirement village. Like NORCs, NOCDs are equally rooted in their locality, with many of the earliest examples forming around public housing and new immigrant communities. They built on years of arts organising, often formalising ad hoc structures. Cataloguing cultural assets that emerged organically over years can be tricky; a 2010 report from a New York working group notes that “to begin to identify the characteristics and benefits of NOCDs” means “recognizing the challenges of defining something that by its very nature is diverse, fluid, and dynamic.” Labelling arts districts as such can help them find funding, but some worry that this may also sap some of their vitality.

Artist organisations have a long history of informality, often skirting the edge of legality. Some of the most celebrated groups in contemporary art have emerged from the New York loft scene, the squats of Amsterdam, the unregulated sprawl of Mexico City, and the post-socialist housing blocks of East Berlin. In fact, there have been numerous examples of the connection between urban renewal and artistic rebirth. The shuttering of factories and the exodus of capital was essential in creating the conditions that helped incubate art movements after World War Two. A number of today’s subsidised art spaces and cultural centres started out as neighbourhood stabilisation programs. Born out of the worst years of disinvestment that followed the flight of professional classes to new suburbs, these centres were often meant as a community-initiated bulwark against abandonment.

While Australian cities never quite suffered the indignities of Detroit or Birmingham, many of the 19th-century structures built during the ‘Marvellous Melbourne’ boom period were on the chopping block. Artists went to these places out of necessity, but when they became cool with the ‘rediscovery’ of urban life by late-80s young professionals, artists had to leapfrog from one former-industrial space to another as rising rents and redevelopment chased them out. While artists are often blamed for the gentrification of working-class neighbourhoods, it is fairer to see them as indicators, canaries in the coalmine. The areas they move to, with a surfeit of cheap but transport-accessible space, are also the ones most likely to be redeveloped – helped along by the cultural cache (both real and cooked up) that is often bestowed on artsy locales and used as a selling point for new development. In Sydney’s rapidly gentrifying Inner West, developers still a few years off building on newly acquired sites have been known to offer artists enticingly low rents to attract said cultural cache. This practice has raised the hackles of those concerned, as artists are simply used as placeholders while ‘condofication’ plans are consolidated.

Artists have tried to push back on development to avoid displacement, sometimes by instigating their own renewal and redevelopment plans with the help of friendly funders and not-for-profit property developers. The Old American Can Factory, a complex of six brick buildings in Brooklyn, New York, has sought to build a 20-storey tower on their site to cross-subsidise the artists and makers who rent space there and to take advantage of rising property prices in the Gowanus neighbourhood in which it’s located. I worked there from 2011 to 2014 and watched as the vacant lot across the street was transformed into an upscale Whole Foods store, and as tyre shops along a polluted industrial canal transformed into speakeasy bars, climbing gyms and craft ice cream shops. Now, a full rezoning of the area is planned. It mixes environmental clean-up, public housing repairs, and subsidies for artist studios and light industrial space.

The plan is not without its critics: Martin Bisi, a recording engineer who has kept a studio in the Can Factory since the 1980s, organised a community group in opposition to the Gowanus rezoning, arguing that it brings in “luxury apartment towers” while doing too little to clean up “deeply toxic land.” However, the rezoning also provides the context for the factory’s expansion plan, which, its proponents argue, will ensure its continued viability as an art space. To ensure developers and local governments hold up their part of these deals, some have sought to enshrine them in complex community development frameworks. But hammering out these agreements can take years – a glacial pace at odds with the fast tempo of nearby residential development.

In Melbourne, the question of what will become of the Nicholas Building has also dragged on as the building’s association has put out feelers to find a ‘friendly partner’ who will underwrite their vertical community with the $84 million required to buy the building. Other potential solutions include selling the structure’s air rights or finding money through illuminated advertising (there is a precedent to this, as the building used to welcome Flinders Street commuters with a giant illuminated Coca-Cola sign on its south side). To date, the City of Melbourne has been keen to support the tenant community, but the Victorian Government has declined to intervene in any way. Yet, the building’s location – just 400 metres north of the Melbourne Arts Precinct – could make it a northern outpost along an arts trail that extends up through the CBD (or so the optimists among us might imagine). The continuation of the building’s hundred-plus creative spaces isn’t just about preserving cultural heritage; it ensures that the city remains a place not just for the enjoyment of art, but an environment where artists and makers can live and work, too.