How commercial co-living aims to redesign renting

The sharing economy increasingly means that we subscribe to a service (transport, music, even clothes and cars) instead of buying the thing. But how does this work with housing?

In mid-January, co-working giant WeWork announced a $2.8 billion cash infusion, doubling its valuation in a little over twelve months. Nine years after launching with a single site in lower Manhattan, WeWork is the largest real estate tenant in both New York and London, and operates a network of 425 locations spanning 27 countries. Today, it is believed to be one of the most valuable privately held venture-backed companies in the world – part of a rarefied club that includes Uber and its Chinese ride-hailing rival DiDi. All three are major players in the rise of the ‘access economy’: selling the convenience of frictionless access to services, versus the burden of owning and maintaining tangible property.

Salesforce first popularised the ‘software-as-a-service’ model at the tail end of the 1990s dot-com boom, offering enterprise clients on-demand access to applications running on remote cloud-based infrastructure, rather than individual licenses. The ‘as-a-service’ terminology has since evolved into generalised shorthand for moves away from simply selling products to providing bundled services (and locking in recurring revenue). Increasingly, this means combining physical and digital systems, developing integrated platforms to support two-way engagement, and leveraging data to understand how products and services are consumed, in order to continually improve and personalise customer experience. We see this shift in everything from music (Spotify), to high-end clothing (Rent the Runway), printers (Xerox), lighting (Philips), and even jet engines (Rolls-Royce).

At its core, WeWork’s business model is pure arbitrage: lease space in bulk from building owners and carve it up into smaller pieces to sublet at a premium.

At its core, WeWork’s business model is pure arbitrage: lease space in bulk from building owners and carve it up into smaller pieces to sublet at a premium. But the company is also engaged in the first large-scale experiment in ‘space-as-a-service’: applying the principles of flexibility and user experience to a growing network of fixed real estate assets. A suite of memberships caters to the fluid requirements of freelancers, start-ups and large corporations alike, while tricked-out common areas, free-flowing craft beer, and in-person and online community management are meant to foster social interaction. WeWork claims the insights gleaned from observing user behaviour en masse allows it to further optimise and customise space.

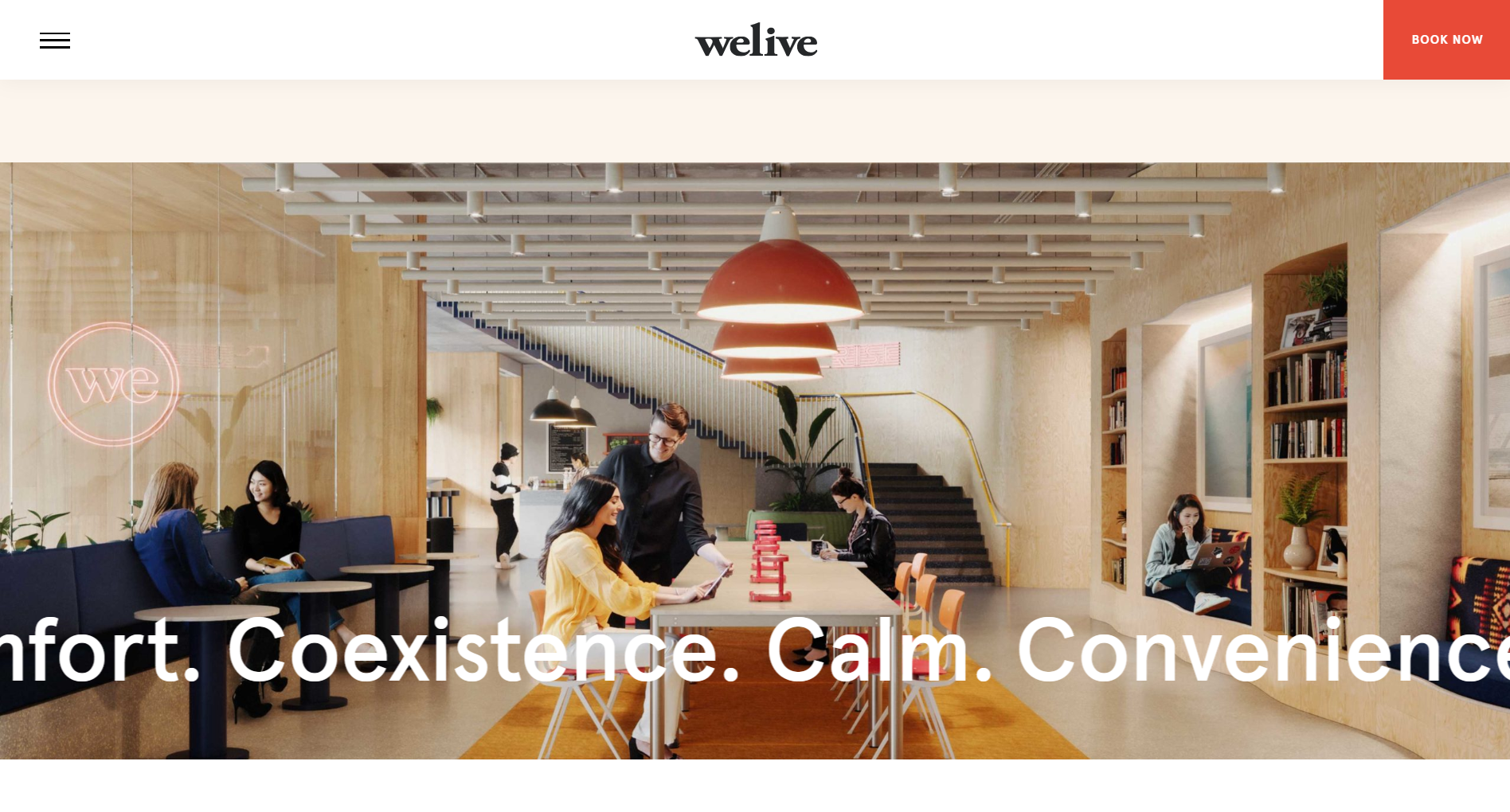

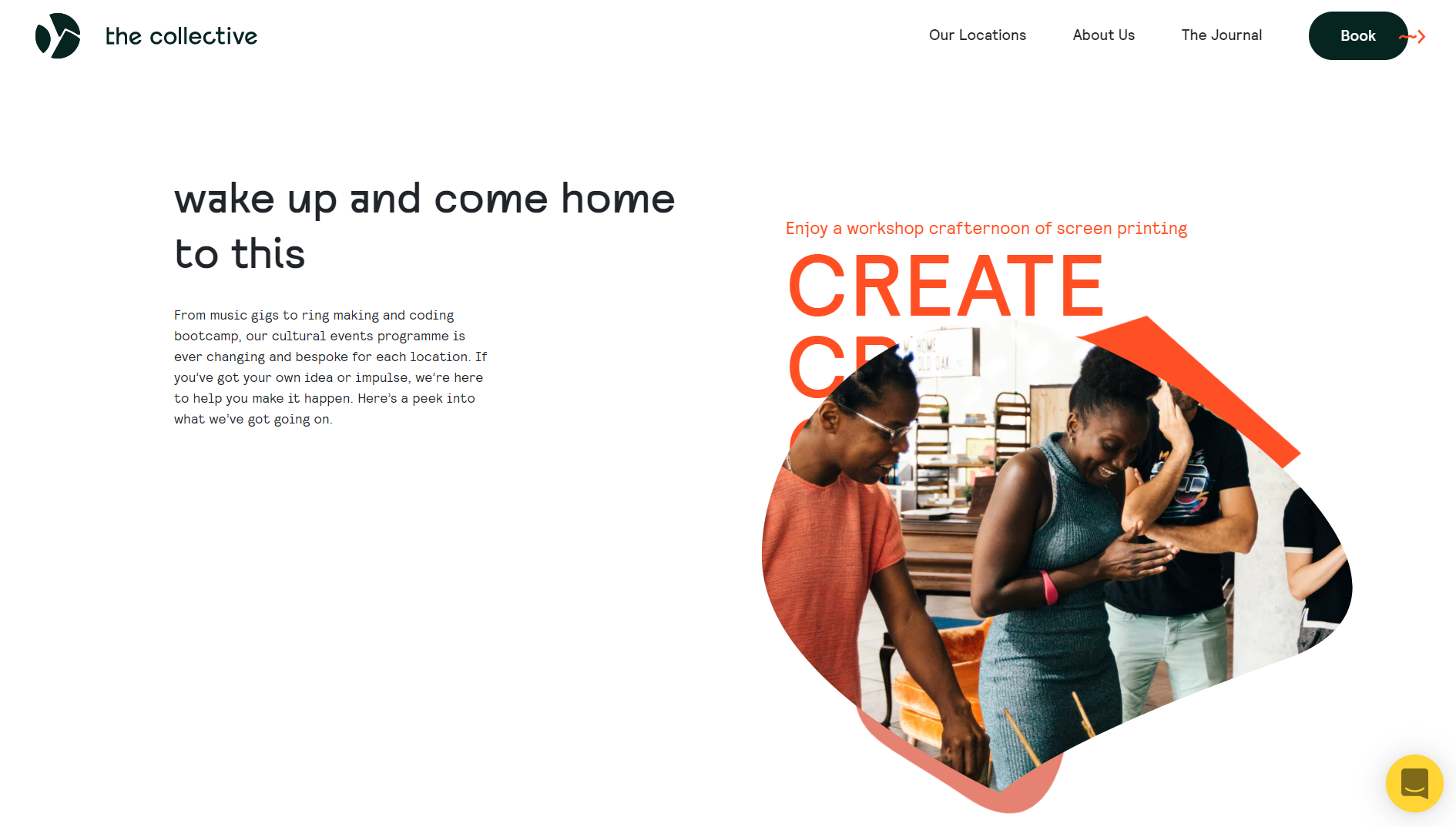

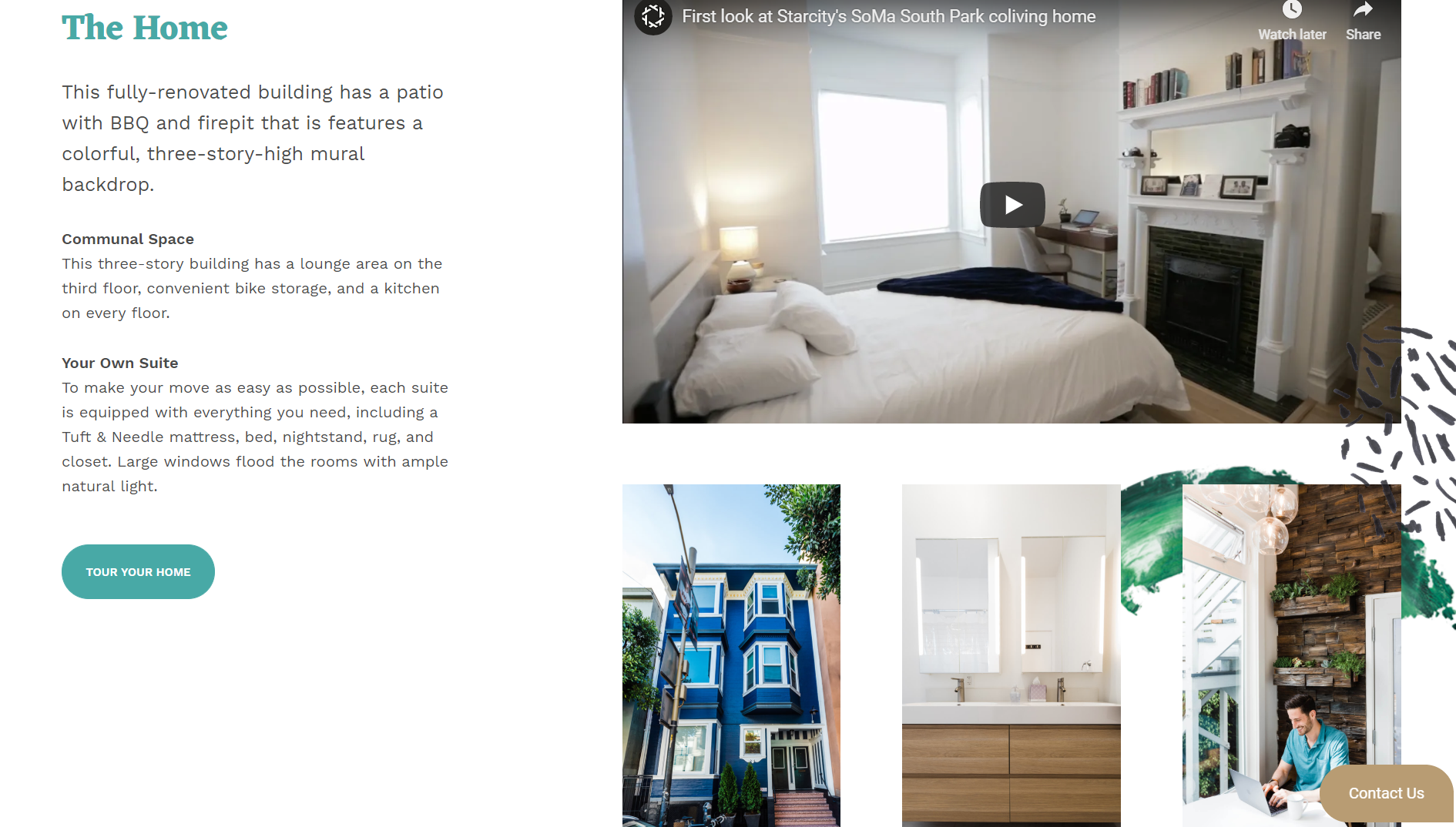

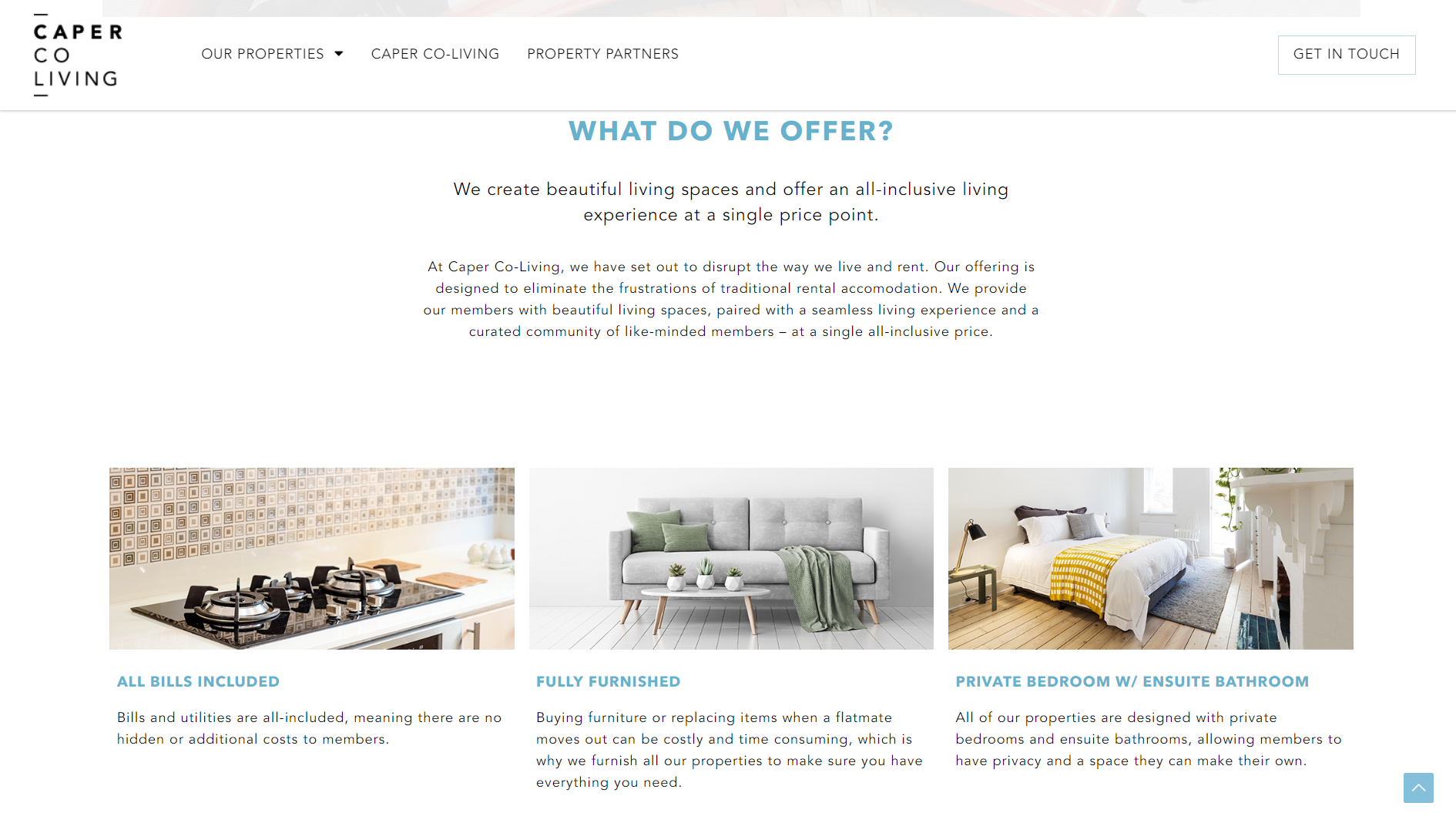

In April 2016, WeWork unveiled “another layer of [its] platform”: a handful of upper floors at its 100 Wall Street location had been converted into 200 residential units. WeLive is part of a rapidly expanding group of ventures offering ‘co-living’ in various forms. Many of these developments are an incongruous mash-up of Bay Area ‘hacker houses’, decades-old Nordic co-housing ideas, traditional serviced apartments, rooming houses, and Airbnb-style short-stay accommodation, designed to cater to the plug-and-play lifestyles of a new generation of itinerant professionals. Marketing tag lines invariably invoke a blend of convenience, comfort and community. This largely entails flexible leases, furnished spaces, event programming, dedicated digital portals, and flat-rate pricing that bundles utilities, high-speed internet, cleaning and rent in all-inclusive plans.

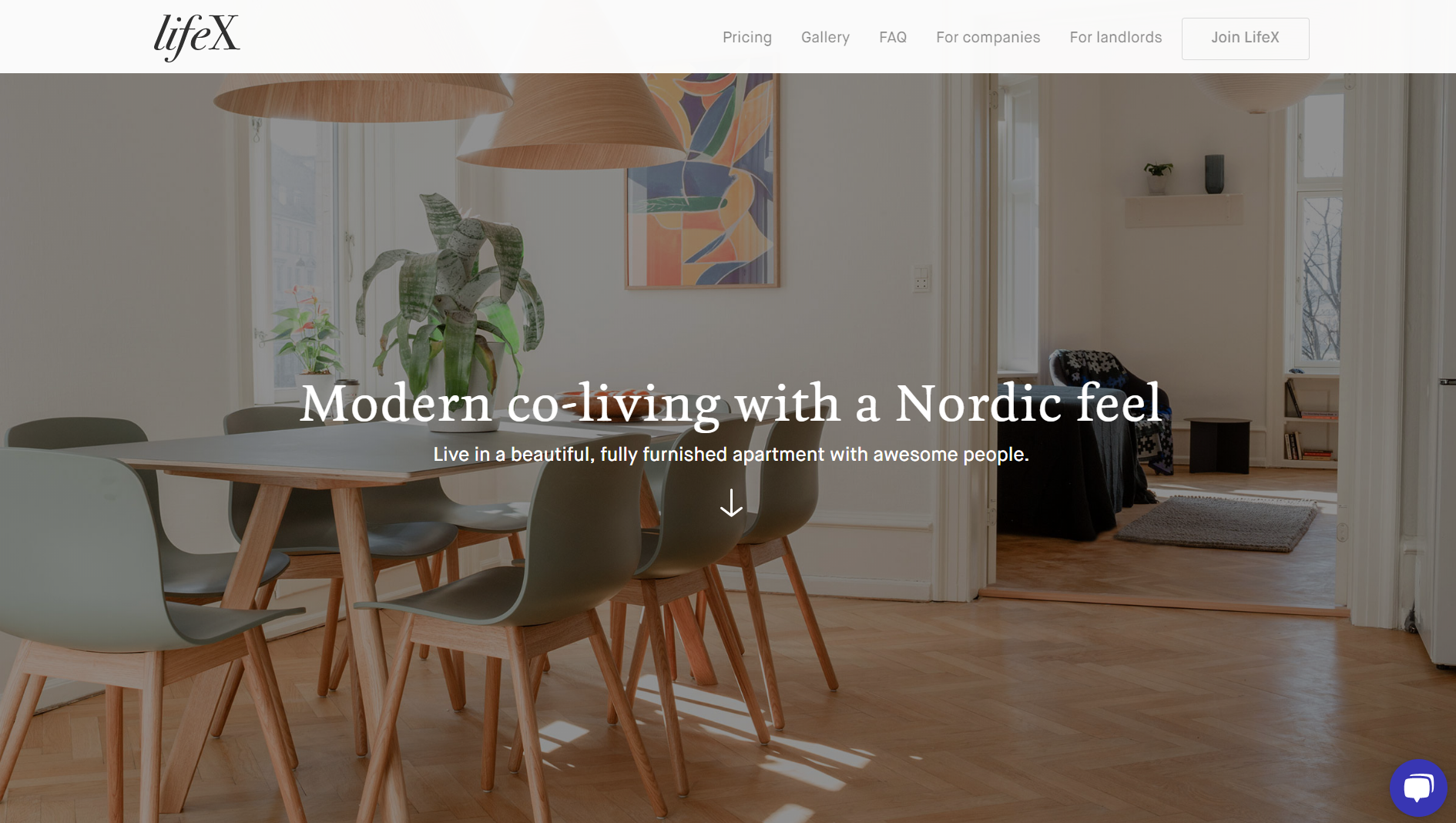

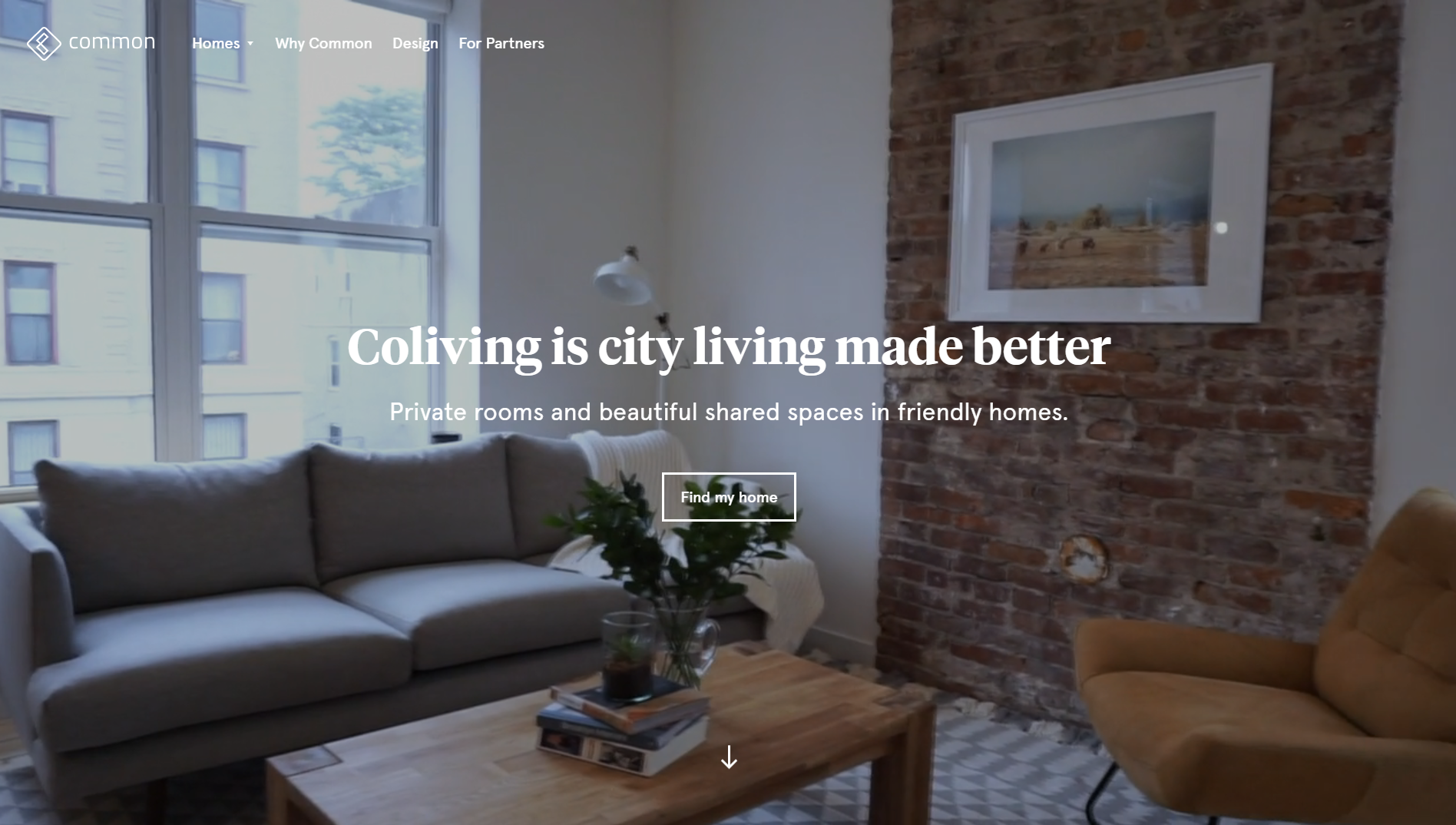

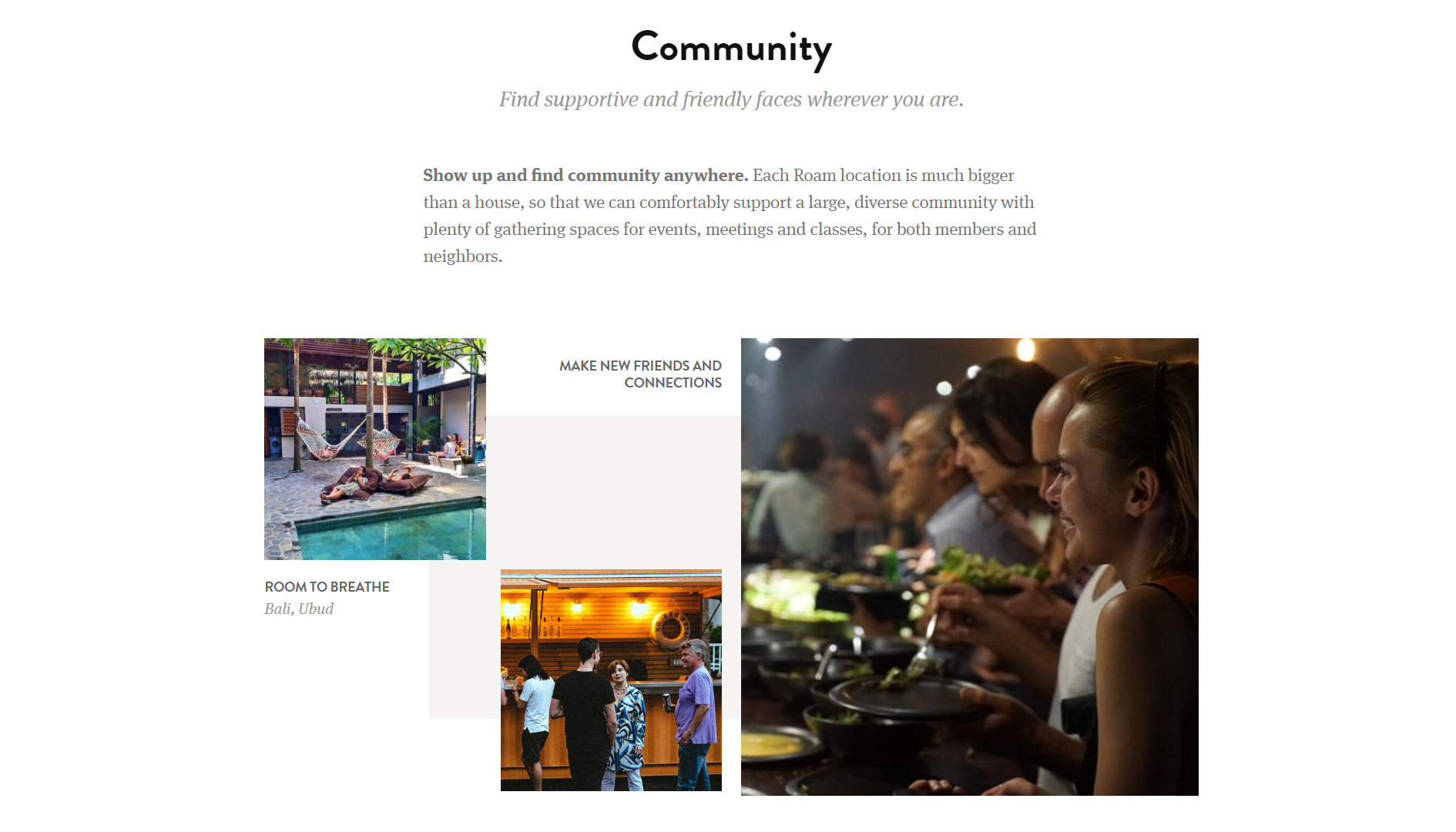

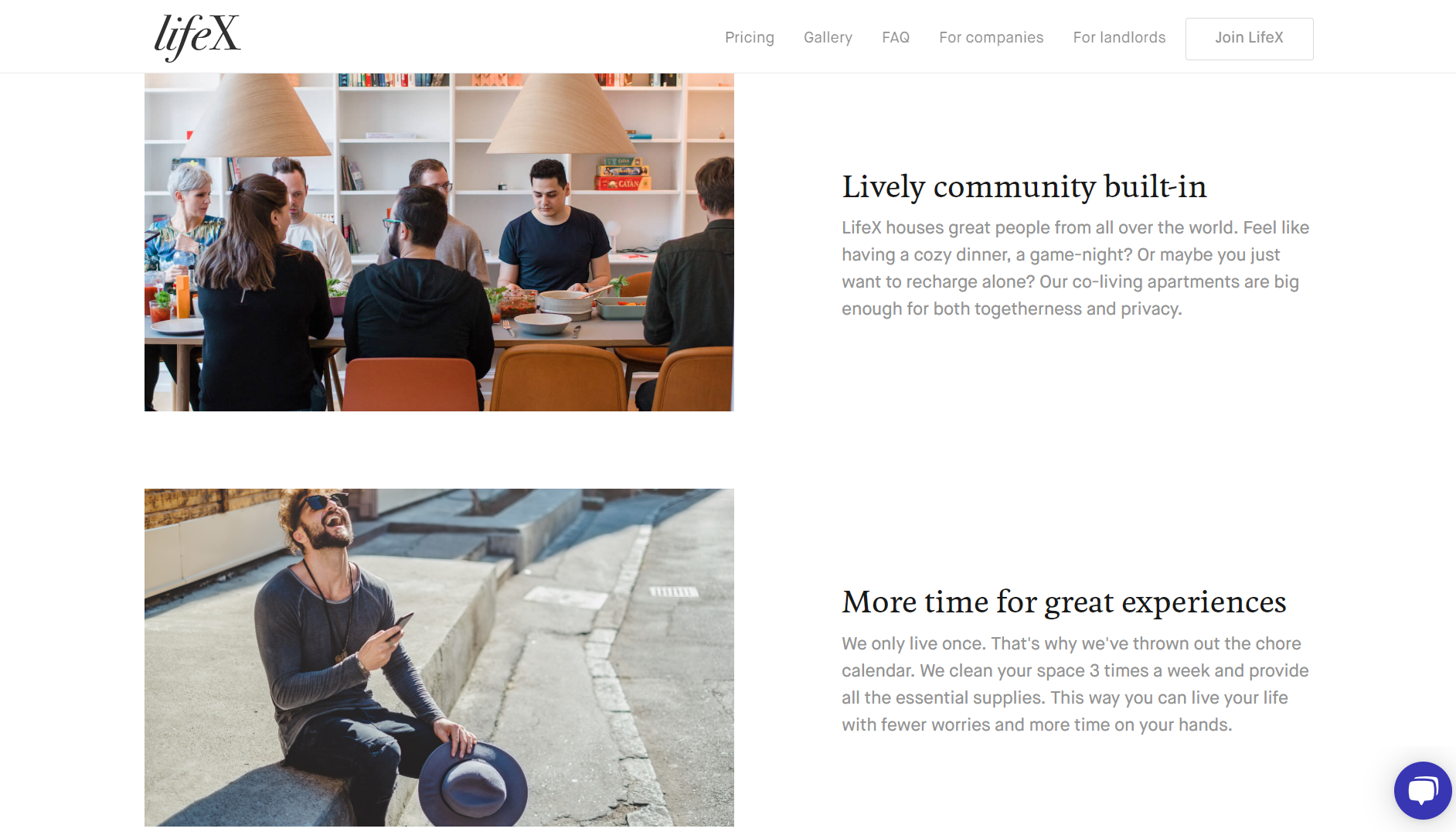

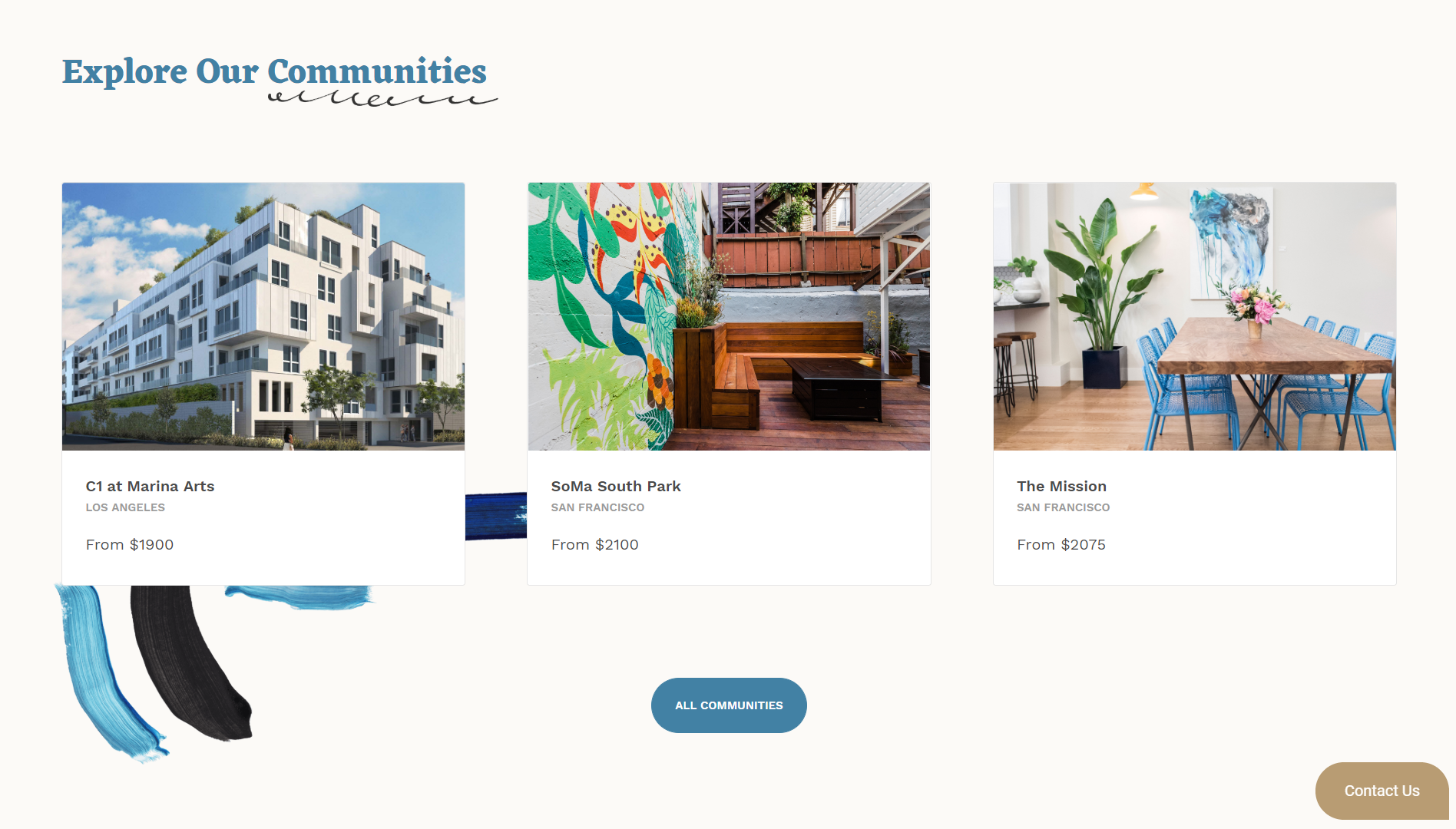

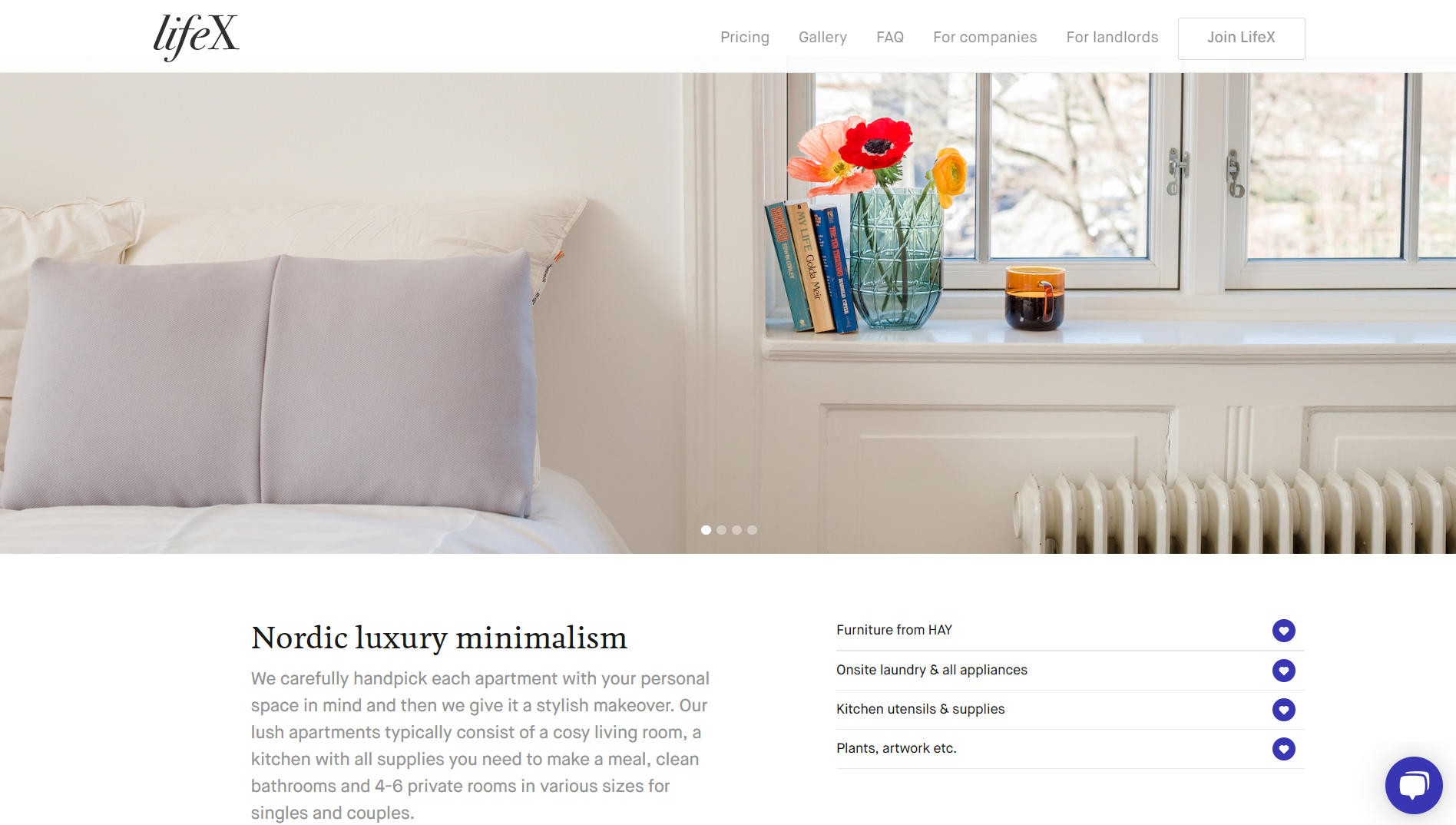

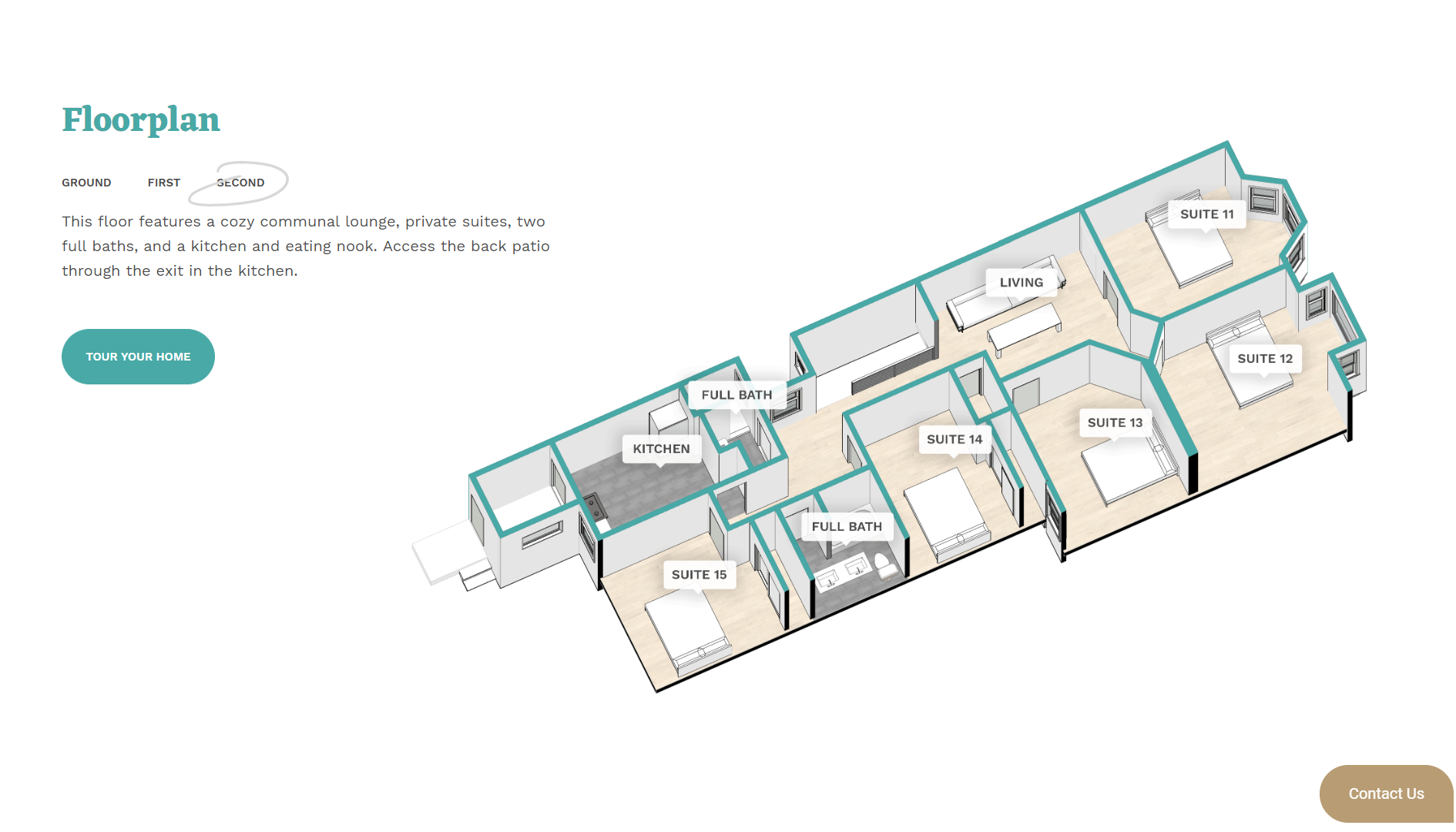

So far, three versions of commercial co-living have emerged. The first is pitched at ‘digital nomads’. Roam operates properties (often converted hotels) in places like Bali and Miami, which combine communal living with co-working facilities in a 21st-century spin on the ‘live/work’ formula coined to market artist lofts in 1970s Soho. The second is closer to an institutionalised version of the share house. LifeX, for instance, manages a network of large apartments (300–350m2) in European capitals like Berlin and Copenhagen. What were once luxury homes for couples or families are converted into curated flat shares for four to eight approved members. Common and Starcity scale this approach to an entire branded mid- or high-rise building, either purpose-built or retrofitted.

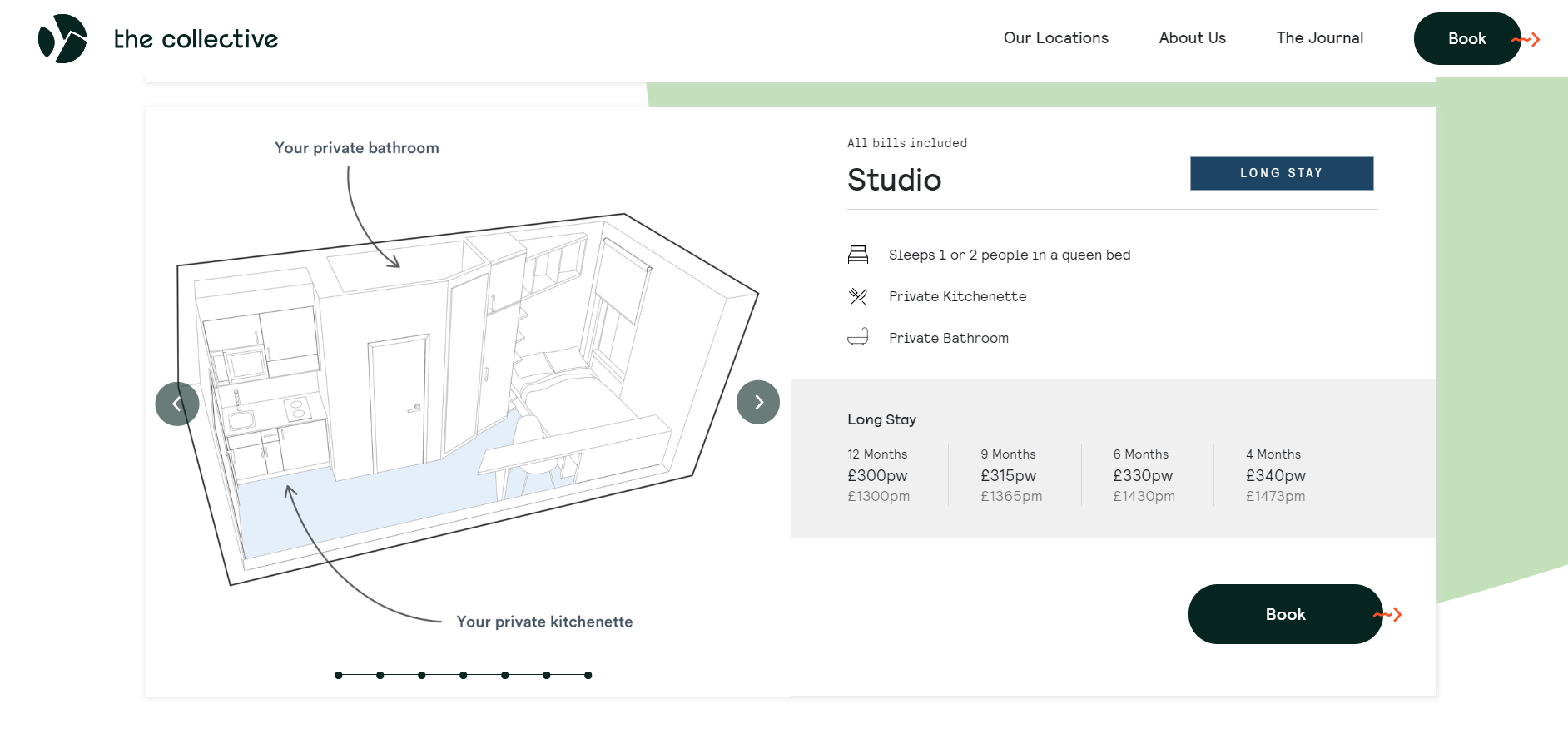

Operators like WeLive and The Collective split the difference. Both offer access to co-working facilities and a range of hotel-style amenities – spas, gyms, a 24/7 concierge, chef’s kitchens, bars and restaurants – but also target longer-term residents. WeLive provides only a limited short-stay option (up to 30 days), while standard leases at The Collective generally run 9 or 12 months. Almost all forms of co-living involve an explicit trade-off: reduce your private footprint in exchange for higher-quality shared spaces. The Collective Old Oak was billed as the largest project of its type when it opened in northwest London in May 2016. Repurposing an office block into a hulking complex of 546 micro-units, a 10m2 room currently sets you back an eye-watering $500 per week.

It’s no coincidence that co-living start-ups have gravitated to cities like Berlin, San Francisco, London and New York. Ostensibly ‘winning’ the battle for capital and talent, they are urban testing-grounds, where rootless and cashed-up tech workers, heated real estate markets, and rising housing pressures add up to a recipe for experimentation. Co-living has attracted legitimate criticism. In particular, the pretext of ‘community’ is often invoked to shrink private space and boost yields, commodifying shared lifestyles for an exclusive market. But, in another sense, these models – and the new generation of build-to-rent projects they have inspired – are also questioning the landlord–tenant relationship, rethinking development approaches for the private rental sector, and adapting existing buildings to respond to changes in how we live.

“In any street… it’s always easy to tell the rented houses. They’re the ones where the lawn isn’t mowed, the plants aren’t watered and the fences aren’t fixed.”

In Australia, the superiority of homeownership has long been elevated to an article of faith. Speaking to building industry representatives in Sydney in 1992, John Hewson, then the federal leader of the opposition, claimed notoriously, “In any street… it’s always easy to tell the rented houses. They’re the ones where the lawn isn’t mowed, the plants aren’t watered and the fences aren’t fixed.” Kick-started by Robert Menzies during the post-war boom, governments on both sides of the aisle have continued to support a range of policies that overtly, and tacitly, promote homeownership over other forms of housing tenure. Three-quarters of respondents in a 2017 ANU housing affordability poll strongly agreed that owning your own home is part of the Australian way of life.

The first legislation governing residential tenancies was only introduced in Victoria in 1980. Until then, aside from a brief window of rent and eviction controls imposed as a national security measure during World War II, the relationship between landlords and tenants had been shaped by archaic common law principles with roots in feudal England. The onus was on renters to ensure that legal protections were specified in the terms of their lease, including in relation to repairs, cleaning, rights of entry, and security deposits. As two reports from the ground-breaking 1975 Commission of Inquiry into Poverty observed, this assumed equal bargaining power and the possibility of negotiation. In reality, landlords offered lease agreements on a ‘take it or leave it’ basis.

Years later, Adrian Bradbrook – a lead author of both reports – likened renters to consumers, as they “consume space and services”. But almost four decades into the consumer-oriented regulatory era he helped bring about, and amid the rollout of Victoria’s latest ‘Rent Fair’ reform package, we’re only just beginning to rebalance the system to better protect and serve tenants, rather than reduce a large swathe of the population to sources of yield for a cottage industry of two million ‘mum and dad’ investors. Meanwhile, the private rental sector is the fastest expanding segment of the housing market. Between 2006 and 2016, it increased at twice the rate of overall household growth, and is now home to more couples, more children, a greater mix of incomes, and a widening pool of long-term renters.

New models will need to strike the right balance between mobility and agency, between quality and affordability, and between community and autonomy.

The Canadian urbanist Richard Florida has argued that similar shifts in the United States point to a “great housing reset”, part of the transition from an industrial to highly clustered knowledge economy. Co-living start-ups certainly believe long-run trend lines are moving in their favour, with some harbouring totalising visions. The former chief operating officer of The Collective mused publicly about eventually offering free housing by monetising its residents (that is, selling data and privileged access to third parties), while Miguel McKelvey, co-founder of WeWork, says the company aspires to be nothing less than “a holistic support system or lifestyle solution”. (Although it has diversified further into gyms [Rise By We] and primary schools [WeGrow], WeLive has fallen far short of initial projections outlined in a leaked 2014 investor deck.)

Demand notwithstanding, if co-living is the most fully realised version of a ‘housing-as-a-service’ approach to date, it’s only one of many possible futures for a reimagined rental experience. New models will need to strike the right balance between mobility and agency, between quality and affordability, and between community and autonomy. And they will need to apply creative strategies to realise the latent potential in the rental stock that already exists. This means engaging simultaneously in spatial design, service design and strategic design. It also means thinking in terms of the ‘extended home’ – not just what can be shared or networked within a single house or building, but also the kinds of collective resources that could be activated on a neighbourhood level.

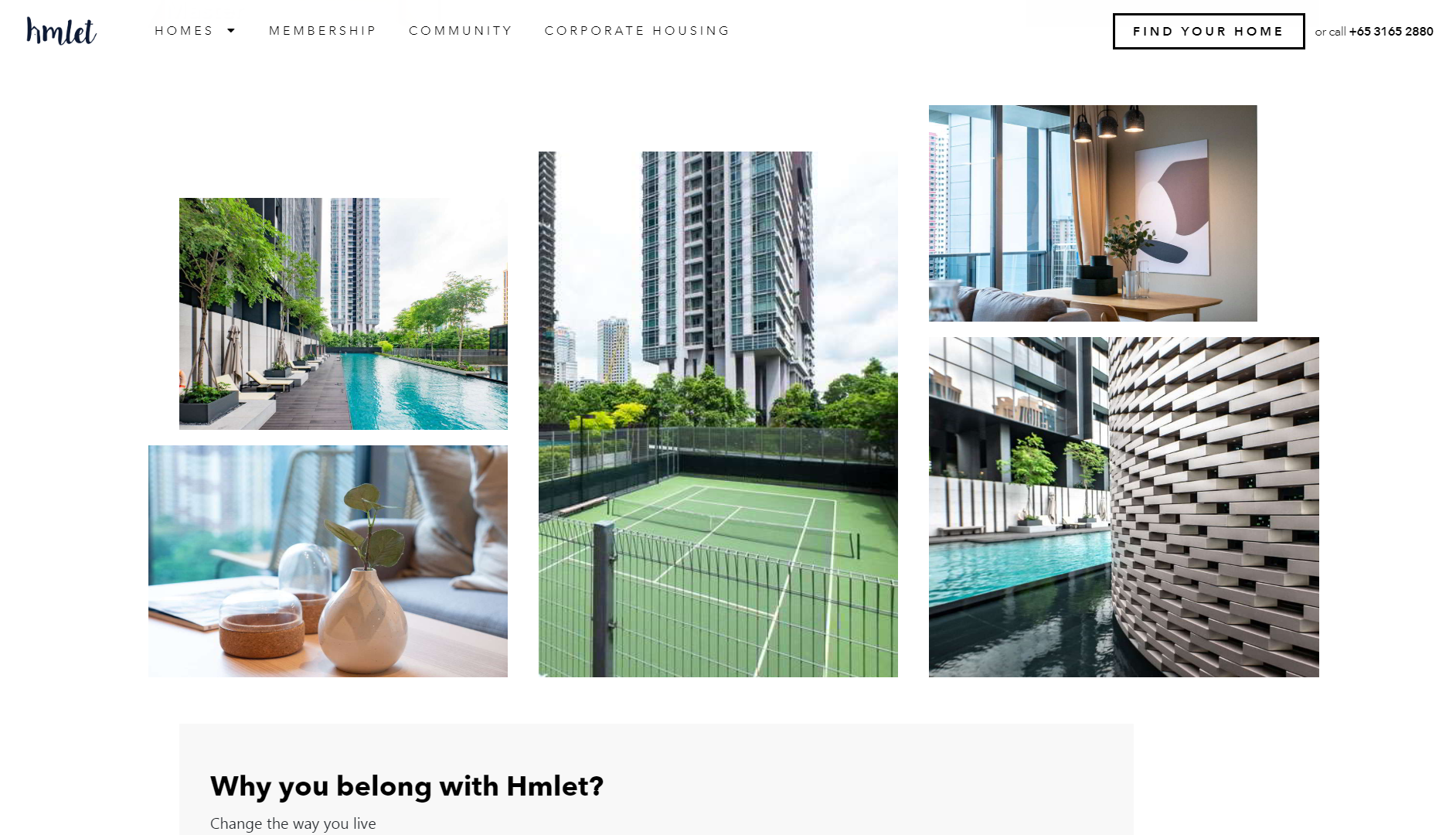

The real question is whether this is possible without a transition to more institutional involvement in the sector. Australia has become a nation of landlords, with tax concessions encouraging a narrow focus on capital gains over long-term returns. Incipient forms of ‘housing-as-a-service’ already exist – witness the rapid growth of student accommodation – and others are on the way. In February, Singapore-based Hmlet entered the Sydney market after acquiring Caper Co-Living, while a flurry of developer-led build-to-rent projects are in the pipeline. But one need only look to cities like Zürich, where 90 percent of residents are tenants and the largest non-profit housing cooperatives manage portfolios of more than 5000 apartments, to see a professionalised, socially-oriented vision at scale. Tweaking the user experience of this model through community-driven digital innovations could offer an alternative path.

Crucially, the social dimension here encompasses more than approaches to financing and affordability. Like co-living developments, the new generation of Zürich cooperatives are experimenting with how to provide a range of shared amenities in a rental context: from yoga rooms, to roof terraces, restaurants and crèches. But instead of looking inward, embracing the ‘hotelisation’ of housing and a vertical form of gated community, recent projects have aspired to an openness and permeability in their design and mix of uses that recreates the diversity and dynamism of urban life in microcosm. As the rental sector emerges as the site where labour market, demographic and technological shifts converge, it may also offer the best hope for our housing stock to catch up with social reality.

We thank Alexis for an in-depth look into co-living, and its potential to deliver true community. This article draws on research Alexis conducted as part of Harvard GSD’s Richard Rogers Fellowship program. It also appears in the new Assemble Papers print issue #11: Transitions – come join us for the launch on 23 May!