Looking at the unseen labour behind deathcare

The origins of this photo series lie in a desire to explore the hidden-in-plain-sight spaces of death and memorialisation that exist in every city as well as to celebrate the labour of Melbourne’s deathcare workers.

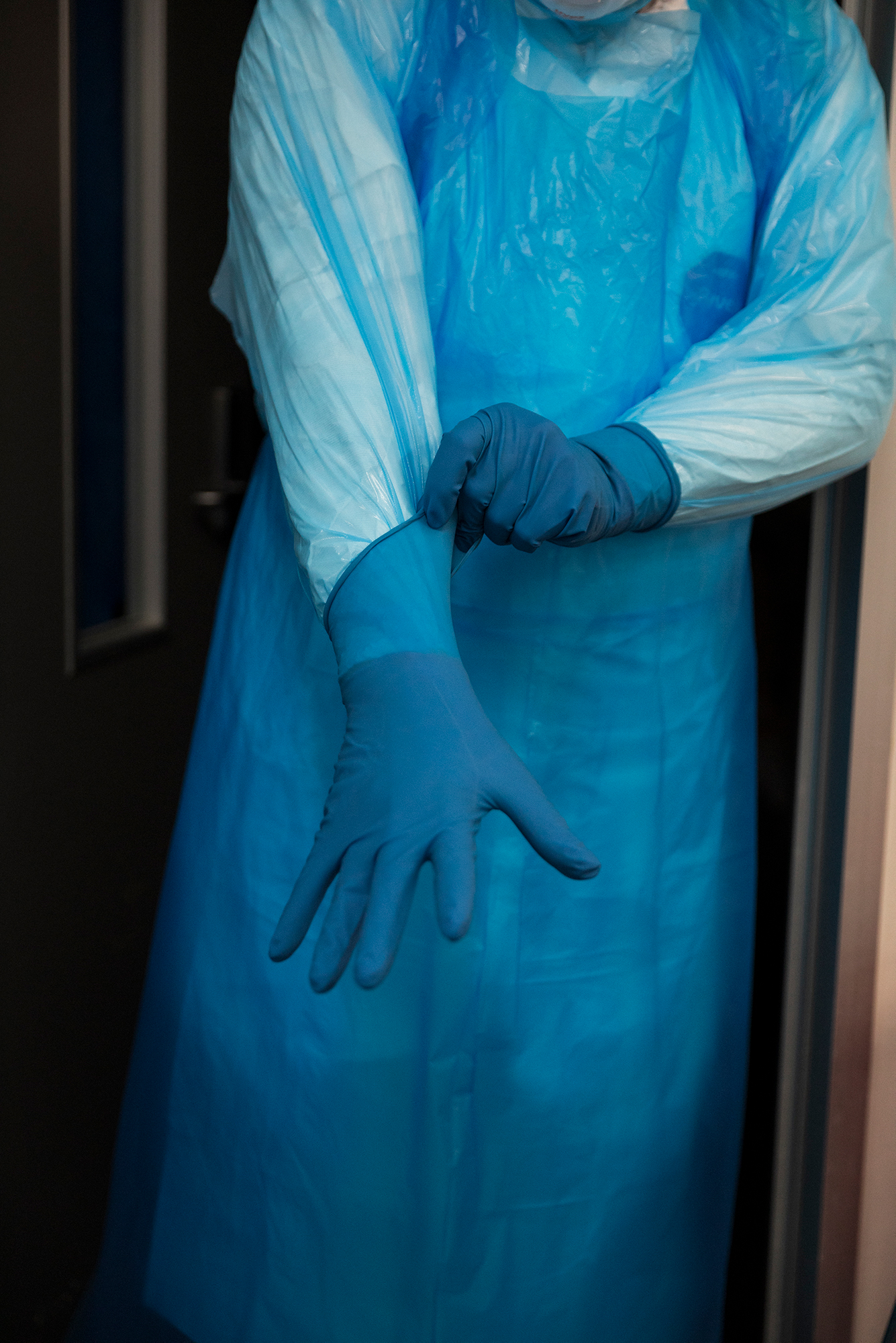

It started as a collaboration between scholars from the DeathTech Research Team at The University of Melbourne and Bri Hammond, a documentary photographer. DeathTech has been studying death, technology, and social change for close to a decade, and much of our research focuses on how death is mediated. During Melbourne’s ‘second wave’, we noticed that ‘frontline’ medical staff were publicly celebrated but death care workers have remained largely unacknowledged. Hammond’s portraits show the people who work not on the frontline, but on the ‘endline.’ In the small details of working environments, the images reveal deathwork to be an essential service and a practice of care, not only for the dying and dead, but also for the bereaved and the wider community.

While Australia has weathered the COVID-19 pandemic relatively unscathed compared to the rest of the world, last year’s ‘second wave’ in Melbourne left the city paralysed for months. Thousands grew seriously ill and over 800 people died. For some, it may have been the first time that thoughts of mortality became front of mind. Images of mass graves and overflowing funeral homes overseas began to be featured on the nightly news. Estate planning services and websites focused on alternative funerals reported higher-than-average traffic. Some even became flippant with a touch of dark humour; comments such as “I reckon you can toss me in the rosebed” proliferated. Beneath such attempts at levity real questions emerged, as people began to consider the materiality of their bodies.

In an era of dramatically extended lifespans in wealthy countries, like Australia – where seniors are becoming the main demographic group – many middle-aged people were suddenly forced to think about what would happen when they died. How did they want their remains treated? A burial? Cremation? Natural burial? Who would be part of the ceremony and what rites would they evoke? Lockdowns and 5km movement restrictions led some to head to local cemeteries to take socially-distanced walks, and to wonder about the provision of space for the dead and the different qualities of memorialis. In sum, the pandemic has helped to illuminate the presence of death in our lives.

Behind the scenes, processes of death and dying command substantial natural resources, including tons of timber for traditional coffins. Annually this takes the hardwood from over 100,000 mature trees in the United States; transportation networks for the repatriation of bodies abroad; and a workforce of thousands in what’s known as the ‘deathcare sector.’ Palliative care nurses, funeral directors, morticians, crematoria operators, and cemetery staff perform roles that are integral to society and their work shapes the built environment, but their labour goes largely unnoticed.

While the pandemic put a new focus on frontline workers in health and safety professions, those whose work involves tending to the dying, dead, and bereaved were not recognised in the same way. Historically stigmatised, the sector has gained in respectability in recent decades but is still marked as a bit odd, good fodder for dark comedy programs like The Casketeers, Buried by the Bernards, Six Feet Under, and Fun Home.

The spaces in our city where deathcare occurs are mostly hidden away from public view, but coexist with activities and spaces of everyday life. They form an invisible layer – a ‘deathscape’ that makes the presence of normal life possible. One of the largest mortuaries in Melbourne is tucked away in an unmarked building behind a Bunnings. While individual bodies do travel in hearses, they also move about the city in innocuous black SUVs or white vans. Signs of death and the final disposition of bodies have shaped infrastructure and land-use across Australia since the beginning of European settlement, but they have been obscured from the public.

Fawkner Memorial Park, founded in 1906 in what was then the very outskirts of Melbourne’s North, is unique amongst cemeteries in that it frankly acknowledges body transport and the infrastructural concerns of burial. Not far from the Upfield Line that serves it, an old train car is parked with an informative panel noting that this “mortuary hearse car” ran the rails from 1903 to 1939 taking Melburnians to their final resting place while hooked to the same engines, and passing the same stations, they commuted to the CBD with. Fawkner also contains an on-site crematorium behind a chapel. It is a squat, workaday, and utterly missable structure, unlike its monumental European counterparts, like the Feuerhalle Simmering, built by the Red Viennese government of the 1920’s to resemble a Silk Road fortress or Kyiv’s brutalist crematorium. The architecture of death and memorialisation in Australia tends to be more retiring, and, like the cement and brass war graves that dot nearly all cemeteries, more one-size-fits-all.

As cemeteries like Fawkner age, and the city grows around them, the once peripheral spaces of death and commemoration have been more tightly woven into the urban fabric. Dog walkers and strollers pass through them and small businesses pop up just outside their gates, but few stop to think too much about the labour or maintenance necessary to the upkeep of these sites, nor do they think about the people who prepare the bodies of the deceased.

This story was produced for our issue #14 Work. To grab a print copy (and pay only postage) head over to our shop.