Divining the future of car parks

Parking structures are everywhere, but seldom remarked on. The shift to automobile-based transport was accomplished so completely in the post-war period that the hulking facilities spread across our cities are taken as a given. Multi-storey car parks are the type of “non-places” that critics of modern built environments like to rail against: largely utilitarian nap zones where automobiles rest for hours on end while their owners go out to have fun, work, or see the dermatologist.

Even car parks of great geopolitical significance—such as the one where “Deep Throat”, the government informant, exposed the Watergate scandal in the U.S.—go largely unacknowledged. (That building was demolished recently, nearly 50 years after the secrets revealed on its oil-stained floors led to the resignation of U.S. President Richard Nixon.) Yet, parking structures do have fans, including those drawn to them because of their quotidian design. This makes sense given that Brutalism’s hard-to-love concrete giants are making a comeback as a new generation discovers them via Instagram. While the glass curtain walls and shiny cladding of new buildings reads as ethereal and untethered from the lives of hard-working city dwellers, honesty in materials gives mid-century garages an aura of grit and authenticity.

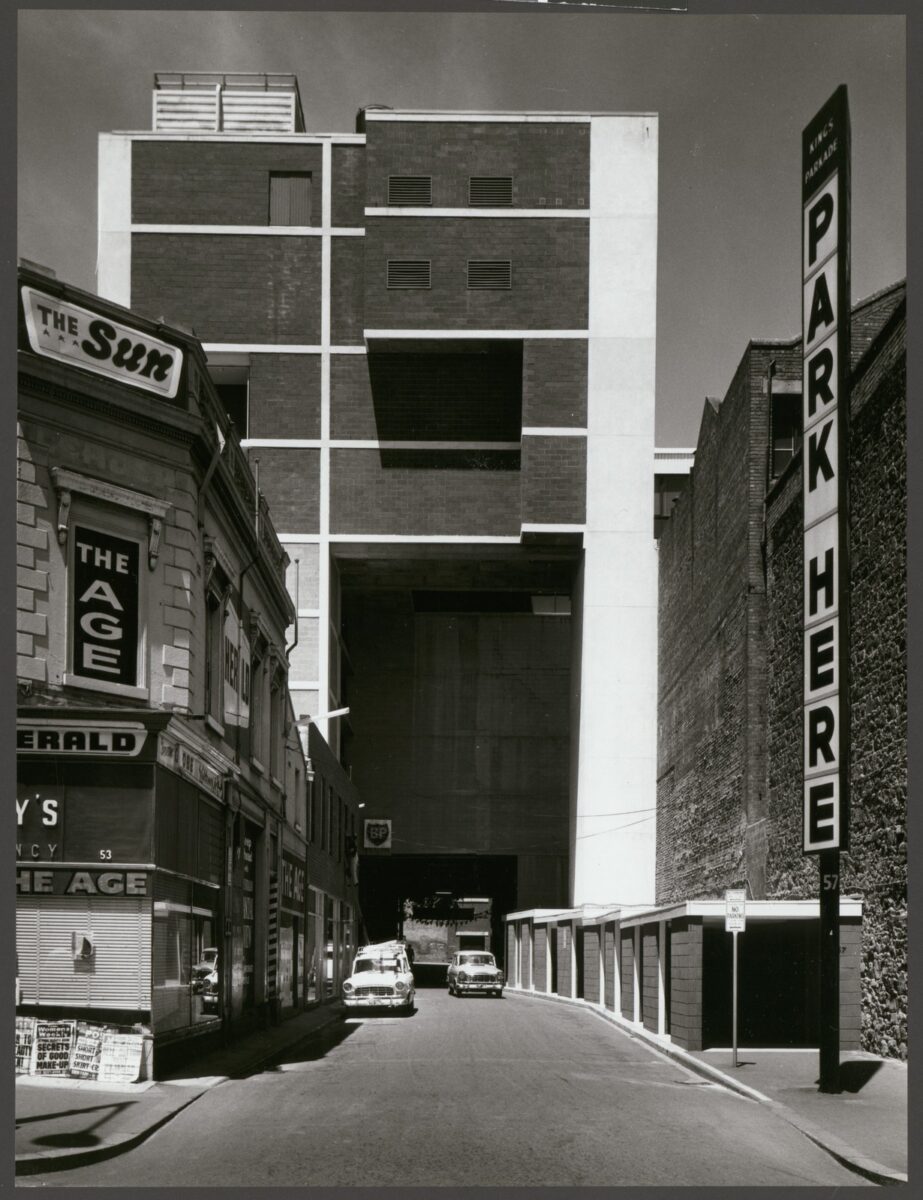

Since the 1990s, there has been a drive to protect significant car parks as exemplars of late-20th century Modernist and Brutalist styles. The garage below the South Lawn at the University of Melbourne has been on the state of Victoria’s Heritage Register since 1994. It’s notable for its innovative use of parabolic columns (their trumpet-shaped capitals accommodate the tree pits for the quad above), and for its cameo in the original Mad Max. Total House, a garage-cum-office on Russell Street was successfully listed in 2014.

More recently, at the end of 2021, the Cardigan Street Car Park that served the already-demolished Royal Women’s Hospital (which went under the wrecking ball in 2018) was recommended for inclusion in the Carlton Heritage Overlay. Preservationists cited the off-form concrete (that shows the grain of the wood formwork in which it was cast) of the building’s balustrades and its “robust and bold” form as worthy of retention. They also noted the building’s resemblance to Paul Rudolph’s Temple Street Parking Garage in New Haven, Connecticut—a Brutalist classic that was completed between 1959 and 1963 while Rudolph was the chair of Yale University’s School of Architecture. To those already quizzical of heritage rules, extending protected status to not one, but three, Melbourne parking structures is another example of how decision makers have “lost the plot.”

Some might ask: what if, instead of scrapping the whole typology, we simply build car parks better? A handful of thoughtfully-executed, even beautiful, ones have been constructed in recent years. One much-lauded riff on the form is the neo-Brutalist garage designed by the Swiss architects Herzog and de Meuron in Miami. The US$65 million project opened in 2010 with haute couture shops and an event space mixed in with parking on open, double-height decks. It was greeted with much fanfare by architecture critics, as a place where “cars are a centerpiece rather than a dirty secret… [sitting] like canapés on a stack of trays.” Some viewed it as a turning point, heralding a new age of mixed used car parks that could accommodate vehicles and people side-by-side. The issue is that only a handful of nice examples exist, and they are often in high-prestige areas. For every ‘canapé tray’ garage there are thousands of scuffed-up, workaday ones.

The parking structures that grab our attention are often those that incorporate striking details—like colourful supergraphics or a patterned facade— in service of ‘prettying up’ their drab exteriors. The Herzog and de Meuron structure is indeed exceptional, but it’s not at all indicative of the car park genre. It broke ground just a few years after —and a stone’s throw from the site—Art Basel set up their annual fair in Miami Beach. The garage is frequently used for fashion shows, LP launches, and weddings and is, tellingly, listed as an ‘event venue’ on Google Maps.

However, if we’re serious about pursuing decarbonisation as a society, we’ll need to dismantle car infrastructure in toto. Weaning ourselves from automobility—a dependency we’ve built up for nearly a century—will mean pushing people towards active transport, redesigning surfaces to stave off the ‘heat island’ effect that comes with too much pavement, and redefining urban parking as an amenity, not a right. This will likely entail the demolition or retrofitting of a lot of car parks; a process that will cause friction, not just with preservationists but with huge swaths of the driving public.

We may have “paved paradise and put up parking lots” but there’s nothing stopping us from turning those lots into spaces where people—not cars— can live, work, and play.

In the City of Melbourne, parking accounts for 12 percent of total floor space. Many of Melbourne’s inner-city car parks have found secondary uses, especially in the last two years as the pandemic emptied out the CBD. For their 2020-21 season, MPavilion left their traditional site in Kings Domain and set up shop on the top floor of Parkade, a 1960s structure already known to foodies because of Soi 38, the Thai eatery tucked away in its base. In December of 2021, ACCA held a screening in conjunction with their Who’s Afraid of Public Space? program at Cardigan House Car Park; and, this month, the Rising festival transformed the Golden Square Parking (between Lonsdale and Lt Bourke streets) into a night market with art installations. These creative activities point to the potential of car parks as multi use spaces. They often have great views, infrastructure in place for running events, and open decks that allow for increased venting and airflow. However, a return to ‘Covid normal’, blustery winter weather, and the dwindling novelty of pop-ups on parking decks might spell the end of these temporary activations. As a friend asked, “Who really wants to hang out in a parking garage?”

For car parks to serve as truly multifunctional spaces they might need extreme makeovers. Without deep cleaning, it’s unclear how safe they are to occupy for long periods of time. Studies suggest that garage attendants, and others chronically exposed to carbon monoxide and petrol, can develop health issues, meaning that using the parking structures in a way where cars and people “play together”, as in the Herzog and de Meuron example, isn’t really feasible for anything other than brief pop-up events. However, once cleaned and sealed, the concrete structures of garages are as good as any other.

Many companies are reclaiming the top floors of car parks to build office suites—a return to an older model—since 1960s car parks, like Parkade and Total House, started their lives with offices on top. Given the current lack of affordable housing in many cities, garage-to-condo conversions are increasingly common. In 2021, John Lewis, the UK retailer, announced that they would create over 10,000 rental units in converted parking spaces above their department stores and supermarkets. These shifts in use have led some developers to design new car parks anticipating future conversion, ditching the slightly-tilted decks of years past for horizontal floors, and providing wiring and lifts from the get-go.

Lastly, when one really immerses themselves in parking policy it becomes clear that car parks may not be the enemy. Parking minimums in new buildings and mega parking structures in city centres still run counter to the goals of mobility justice, but smaller, localised car parks —like those developed in Japan— or mobility hubs for carsharing or electric vehicles may actually free up neighbourhood streets for cycling infrastructure, plantings, and wider footpaths. We may have, in the words of Joni Mitchell, “paved paradise and put up parking lots” but there’s nothing stopping us from turning those lots into spaces where people—not cars— can live, work, and play.