How to radically rethink housing in favour of older people

Growing older tomorrow will be very different than today. As the retirement of Australians relies upon the asset of the family home (with superannuation) and as home ownership becomes increasingly impossible for a huge swathe of younger Australians, Sibling Architecture investigates possible models of dwelling through the lens of an ageing population in New Agency: The future of dwelling and ageing. In this outline of three years of research by Sibling Architecture, published in 2021, they look at current and future housing trends, qualitative research and design speculation on what a future model may look like in Australia.

Retirement, in Australia, has typically been made possible through the purchasing of property during one’s working life.

Baby boomers were assisted by a tool kit of schemes and levers (negative gearing, capital gains tax concessions, first-home owners grant, and record-low interest rates) to buy up big. These assets, with values skyrocketing over the last decade, were then sold or rented to fund the twilight years.

But there is an increasing trend of older people in Australian cities who cannot afford to age-in-place. This cohort will expand into the future when today’s young grow older and are no longer able to own their home prior to retirement.

There are many factors that exacerbate this condition:

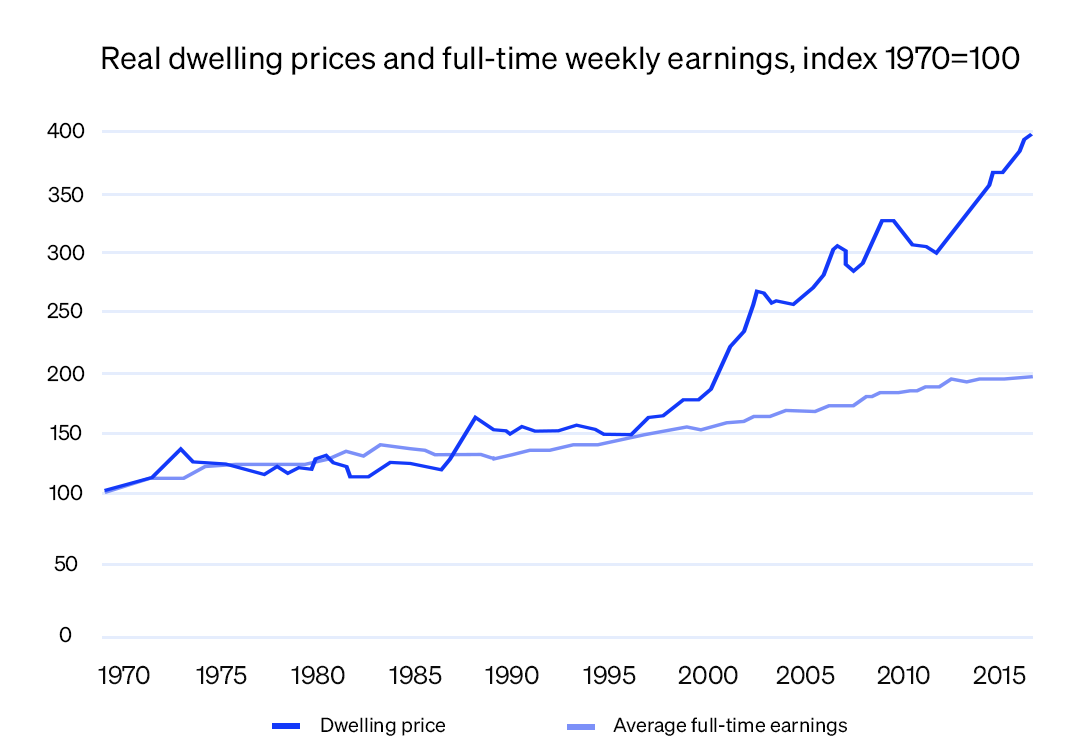

1. Home ownership tomorrow – wage growth has not kept up with the fast growth in property values. As such, home ownership has become even further out of reach for middle-income Australians, let alone people on below-average incomes.

2. Rental costs – average rental costs outweigh government pensions.

3. Superannuation/retirement – the average super balance at retirement is just $197,000 for men, and $105,000 for women. An average couple needs just over $500,000 to ensure a comfortable retirement, which also assumes ownership of a home.

4. Exiting Australian cities – typically younger professionals move to the suburbs in order to purchase a home. Others, particularly single women, move out due to unaffordability as they grow older. Some students cannot afford to rent in cities.

What models of housing can benefit our elders today and tomorrow? It depends upon what we are prepared to share.

An increasingly older population will put pressure on the wider community to assist its elders around issues of civic participation, medical care, pensions, public space, entertainment, accessibility, employment and housing. In Australia, supporting these issues often falls on the government, and issues can be compounded if a larger percentage of the population is not working and the tax-base shrinks, and when some wealthier cohorts derive benefits from taxation policy in their older age.

To partly mitigate the strain of an ageing population on state pensions, superannuation was introduced to support workers in their retirement. Approximately nine percent of an employee’s wage is paid into a super account to provide an income stream upon retirement. Since it is compulsory to participate, Australia’s superannuation system is often ranked as one of the largest in the world, being measured at 2.7 trillion dollars (2018). This also makes the retirement savings pool as one of Australia’s largest sources for investment funds.

With the average Australian salary at around $60,000, most Australians will not be able to retire at the age of 65 on the figures outlined above. Average superannuation balances at the time of retirement (assumed to be age 60 to 64) in 2015-16 were $270,710 for men and $157,050 for women, which fall far short of the figures suggested by the Australian Securities Investment Commission (ASIC) should we be seeing life expectancies into our 80s. This, along with the possibility of home ownership declining in Australia , shows that many will be working for longer into their later years.

What’s more, housing is increasingly becoming expensive in Australia. Increasingly, people are spending more of their income on housing, particularly as housing prices are rising much quicker than the average wage growth. (This is acute with low-income households.) This has contributed to a lack of affordable housing for people right now and as they age into the future, particularly for those who currently do not own a home.

It is clear that the future of ageing tomorrow will be very different than today if the current trend continues. People will not be able to afford retirement let alone a house. Something needs to shift dramatically in Australian society to ensure people age with dignity.

Adapting the model

There are many models that have emerged that provide an alternative to the typical market-driven housing market found in many Australian cities, suburbs and regions, outside of the home occupier detached house or investor apartment. What models of housing can benefit our elders today and tomorrow? It depends upon what we are prepared to share.

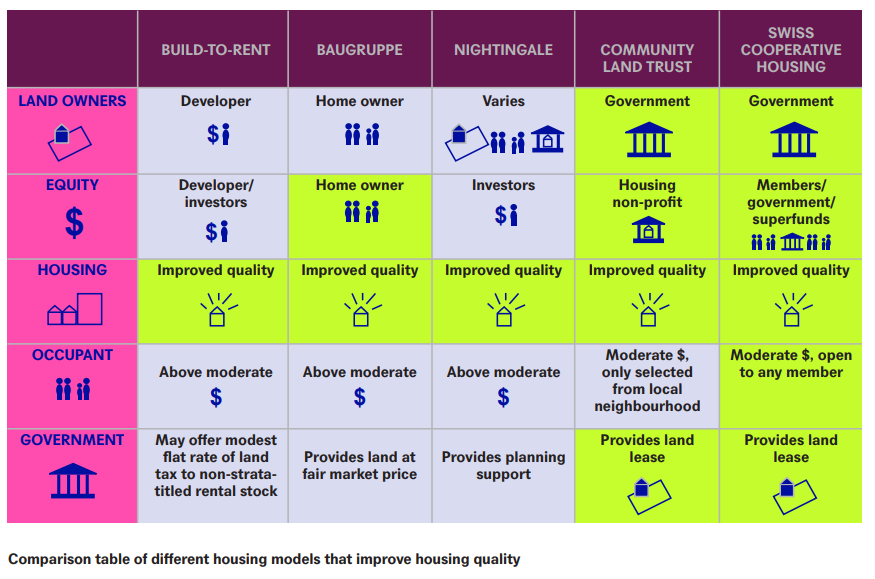

There is a spectrum of housing delivery models available. This research only identifies eight: build-to-rent, Nightingale, Swiss cooperative housing, Baugruppe, tiny homes, public housing, Airbnb and community land trusts. From comparing these examples, five scaleable models that demonstrate co-housing principles of shared space are privileged for further analysis (in the table above), which all can demonstrate improved quality in housing design.

Experiments are important to ignite systemic change through demonstration. They can unleash civic participation, political desires and policy-maker imaginations.

Collaborative housing models — where there is collaboration between housing providers and occupiers — is essential to improving housing quality as a deliberative process mobilises actors and recognises housing as a common good. This is achieved in four of the models in the table: Baugruppe, community land-trust, cooperative and Nightingale models. Collaborative models mobilise actors through a framework for occupants to be part of decision-making processes. This builds the capacity of participants to have knowledge about housing, and builds a community among occupiers.

This shifts citizens from a passive agent — or home purchaser — to being part of a radical living experiment. The extensive collaboration between architect and occupiers, along with removing market pressures to extract profits, can unleash sociotechnological innovation in housing delivery from spatial planning to construction methods. Collaborative models can recognise housing as a common good.

This is evident in CLT and cooperative models where membership to an organisation ensures not only democratic decision-making, but shared equity. In these models, surplus capital is directed back into the common good through the entity, which can be used to replicate more housing. These models also decouple land and property value with government retaining ownership of the land for the common good. (In Australia, and in other locations, there is the potential for this land to be given back, and leased off, its Traditional Owners.) The Swiss cooperative model extends past the CLT model in terms of delivering the largest common benefit by providing houses for rent rather than purchase, and more diverse individual and collective spaces, including mixed-use amenity. It also extends its membership base much more broadly beyond the local neighbourhood.

A New Agency model: extending the cooperative

The Swiss cooperative housing model can metamorphose in Australia to support affordable housing for young and old through rethinking finances, land ownership, and rental relationships. The model finds finance through a cooperative membership fee for the loan deposit, which is supported in its start-up phase with government funds and loan guarantees. There is also the potential to leverage superfunds in this process, which echoes the recent trend of Australian superannuation funds investing in affordable housing supply more broadly.

Land ownership is retained by a government that offers a long lease to the housing cooperative. The cooperative retains ownership of the building on this land. The separation of land and building ownership ensures that, one, land remains in public hands, and two, that the site is decoupled from market pressures to sell land.

Cooperative management ensures that the project supports the needs of its members, including in the planning and design phases. This can lead to innovation in housing design from considering designing for the whole-of-life, special needs, and introducing shared common spaces for the cooperative, and for the broader community.

There is no one panacea to solve the lack of affordable housing in Australian cities: it takes policy, political will, individual champions, non-profits, property developers and finance among many other factors to challenge the dominance of housing markets shaped by profit.

A cooperative housing model responds to changing demographics in Australian cities by targeting two groups — students and elders — who may struggle to find affordable housing in heated property markets. They can be supported with below-market rent, particularly as in the Zurich model, cooperative rents are twenty percent below market rate. This can be extended for cooperative residents by offering a ‘time contribution’ for (further) reduced rent. This sees residents, young and old, contribute a certain number of hours per month in building maintenance, basic care services or cooperative pursuits (co-op cafe, cultural programming) for the community. The time contribution may outweigh the financial costs associated with aged care.

The housing model is scaleable and replicable. This is achieved through a revolving fund where start-up capital, once-paid off at one location, is distributed to another cooperative. However, government land supply is an issue that requires more attention. And so is the need for more political will.

The future of ageing and dwelling

Australia’s housing market is dominated by three typical tenure models — private owner-occupied, private rental, and social rental housing — with private owner-occupied housing dominating. With the private owner-occupied housing market becoming out-of-reach for many, other solutions are needed to deliver quality and affordable housing, including for one’s retirement.

There is no one panacea to solve the lack of affordable housing in Australian cities: it takes policy, political will, individual champions, non-profits, property developers and finance among many other factors to challenge the dominance of housing markets shaped by profit.

Experiments are important to ignite systemic change through demonstration. They can unleash civic participation, political desires and policy-maker imaginations. Government authorities must promote and support cooperative housing experiments, such as inscribing cooperatives into land-use and planning frameworks. It is integral that any model integrates our elders so that they have the option to age-in-place.

Edited excerpt from New Agency: The future of dwelling and ageing.