How street vendors could improve Melbourne’s public spaces

Melbourne is (touch wood) finally exiting a dark winter of homebound isolation, hour-long walks and delivery food. As good weather arrives and rules are loosened, the government has outlined a pathogen-conscious plan for restaurant reopening that relies heavily on outdoor dining. This has already spurred debate about how we allot space on our streets and footpaths – for cafes, trading, mobility and parking – and how we might best encourage street life.

Outdoor spaces, once seen as secondary, are now front and centre of conversations on commerce and leisure as they are being retrofitted to accommodate new decks and street furniture for safe dining. Some of these interventions have put traditional street trading in the crosshairs, as well-funded establishments join their informal counterparts on the city’s footpaths.

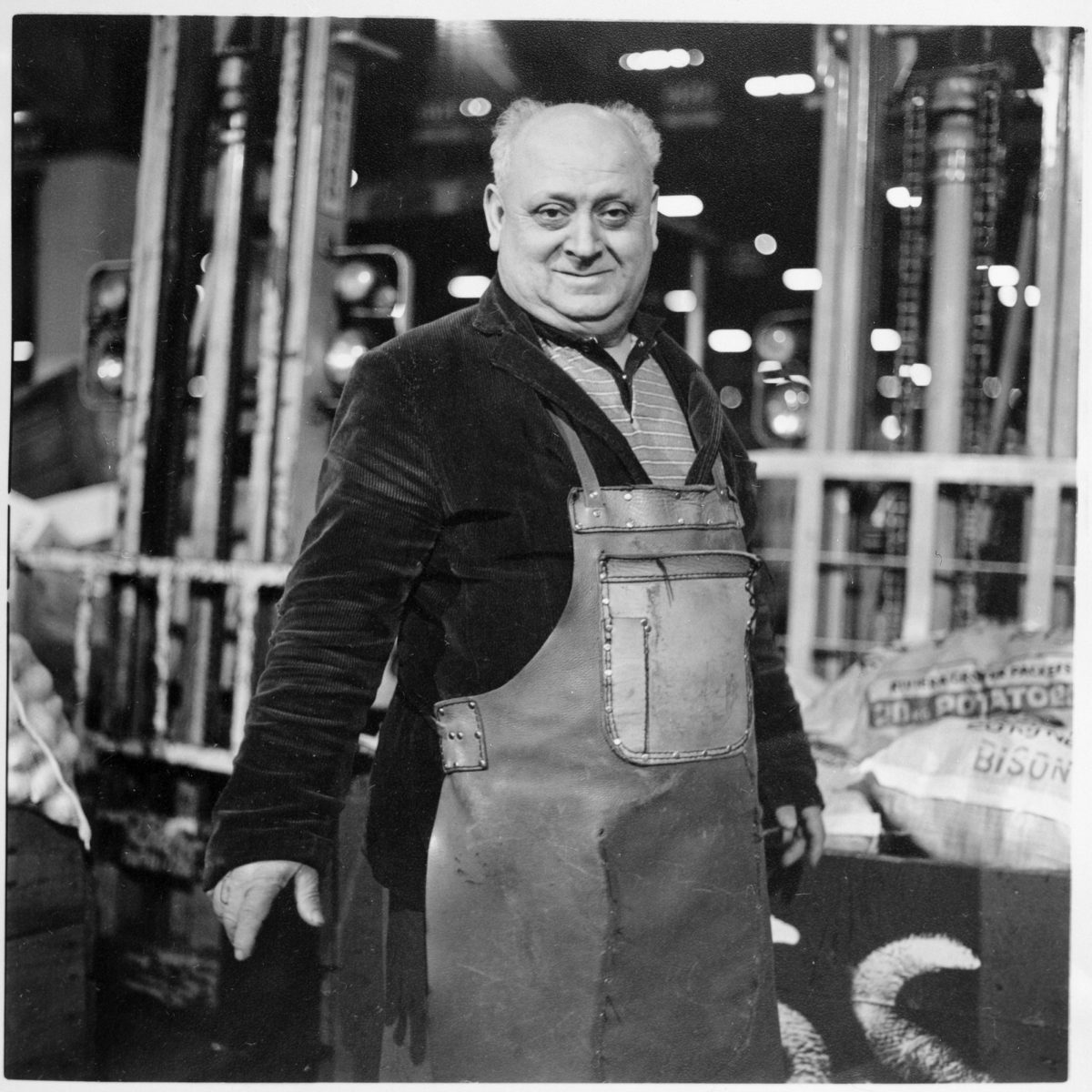

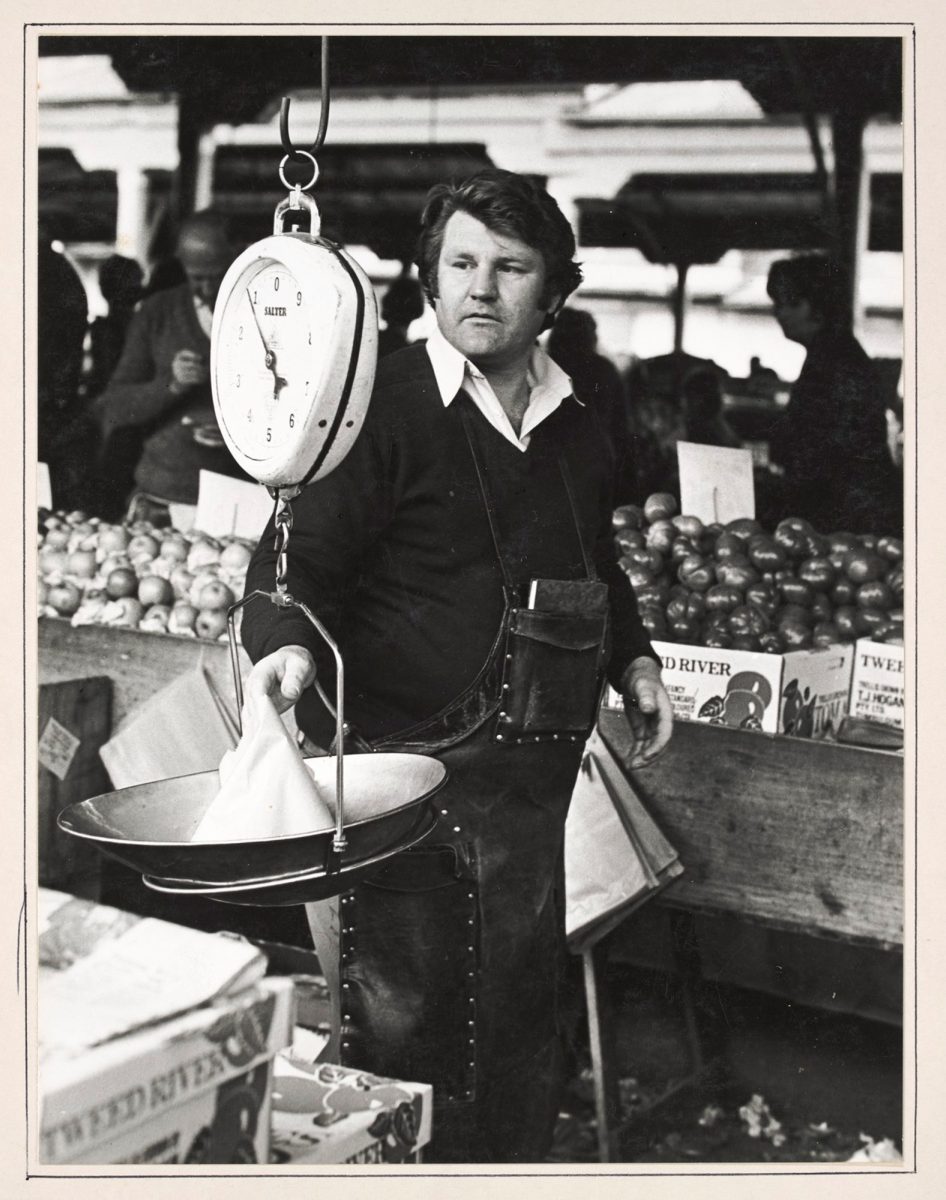

While streets have been the focal point of public life since ancient times, the broad 20th-century trend was away from the street and toward the arcade, the covered market and, later, the mall. Streets were spaces of impropriety. Being ‘of the streets’ became a slur. Eating outdoors, a practice introduced to many Anglo societies by Mediterranean migrants, was reluctantly deemed acceptable, but cafe spaces were often sited on slightly raised plazas or behind rails. Street trading was also curtailed as central business districts modernised and banished all but the most staid vendors (primarily grab-and-go kiosks to supply coffee and sandwiches to office workers rushing by). The clogged, buzzing streets of 19th-century cities slowly gave way to windswept plazas of ‘efficient’ thoroughfares paved for speed and lacking in places to congregate. Streets were to be rushed through – the very act of stopping to enjoy them as places was termed ‘loitering’, and strictly forbidden.

“Spatially, we should look at ways to learn from and adapt the bottom-up tactics of footpath traders and others who have activated and improved public spaces.”

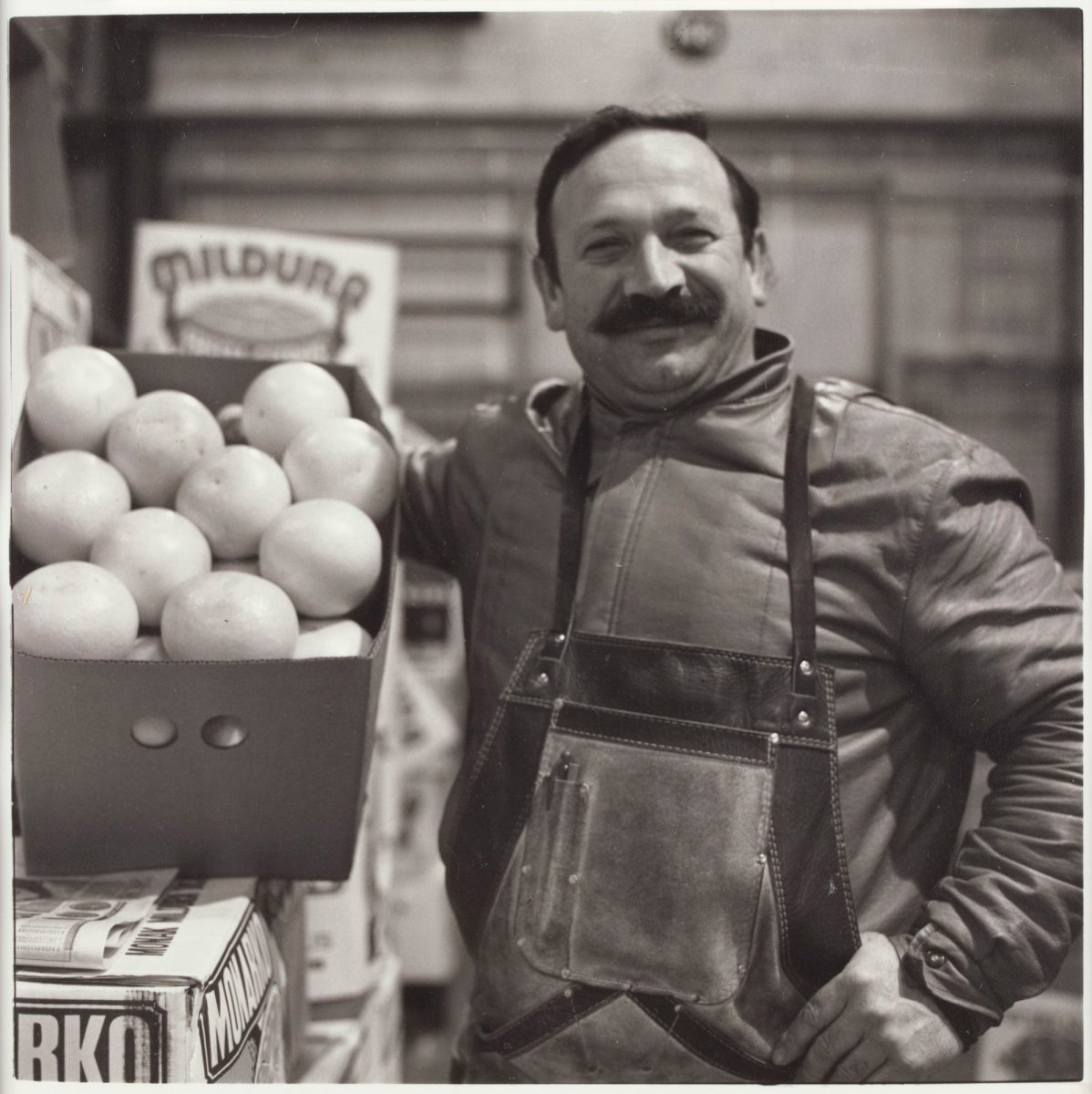

In Australia, like most other industrialised countries, trading has been so thoroughly removed from the street as to make its reintroduction novel, a marker of urban authenticity. Dissatisfied with atomisation and the soullessness of the postwar supermarket and shopping strip, Melburnians embraced local shopping. This started with the preservation and renewal of historic covered markets, such as Queen Victoria Market (upgraded in 1975), South Melbourne Market (with a number of periodic upgrades) and Footscray Market (made over in 1981); it continued with the pedestrianisation of laneways in the 1990s and the establishment of Melbourne Farmers Markets in 2002. These put forward new forms of street sociability and trading, but did not change the basic principles of commerce, licensing or street design. It’s only in the last decade, with the social-media-friendly food truck craze, that food sales have become untethered from brick-and-mortar storefronts. With little more than a panel van, a generator and an Instagram account, traders have been able to attract considerable attention, even while moving from location to location. In fact, this mobility has helped them to introduce an element of novelty into the humdrum practice of feeding people. High-end snacks appeal to millennials, in particular, by virtue of their obsession with food trends and precarious finances; such people want to go out without committing to a sit-down dinner.

A history of street eats

In different eras, various foods have served as a quick snack. In early 19th-century New York, oysters were the street food of choice (they were harvested close by in a still relatively clean harbour); in Amsterdam, it was raw herring with onions; and across the Indian subcontinent, it was (and is) chaat, a mixture of fried dough and spices. These were humble staples of the working classes, but all have gained recognition as culturally important foods; some, like eating oysters, have shot up the social ladder and become markers of luxury status. These foods change with shifts in demographics, availability and concerns over hygiene. Increased oversight and expanded palettes have led middle-class consumers to seek out ‘ethnic’ food stands in search of culinary adventure; roast chestnuts have given way to bánh mì and onigiri. Social media and the ‘foodie revolution’ of the last 20 years have transformed some sidewalk chefs into culinary stars, but most still go uncelebrated.

“With time, we may be able to loosen some of the rigidity imposed on the city’s streets, making it a more equal – and more interesting – place to live.”

Many of the ‘new wave’ of food trucks popularised in the United States riff off of the romantic past of hawkers and pushcarts. But the primary inspiration comes from informal vendors in ethnic enclaves. ‘Mom and pop’ taco, torta and pierogi trucks are widely credited with reinvigorating urban space in cities such as Los Angeles and Chicago; in turn, these initiatives have helped spur high-end food trucks. While there are some remarkable examples of migrant-owned food trucks spinning off into prosperous restaurants, the trope of food-stand-turned-global-franchise is more of an ideal than an actuality. In truth, it’s very easy for small-scale enterprises to run afoul of permitting laws. When periodically cracking down on food trucks, it’s usually the more deep-pocketed ‘concept carts’ that can hire lawyers to navigate their way out of trouble.

Informal street vending has been met with consternation by some. Historically, leaseholders paying high-dollar CBD rents have been antagonistic to traders who have set up carts or tables with goods for sale. Public policy is not on the side of these traders, either. In the City of Melbourne, there are only a handful of permits available for street sales, and most are tied to long-term kiosks or seasonal markets. There is also a marked contrast between the public’s love of food vendors (both high- and low-brow) and their relative antipathy towards traders selling inedible goods (for several years, Victorian food vendors have also been able to make use of the Department of Health and Human Services’ special website for fast-tracked permitting). At the behest of store owners, many cities have tightened laws and ramped up enforcement of people selling mobile phone cases, scarves and pot plants. Efforts to make these traders ‘play by the rules’ often do not acknowledge how difficult it can be to raise capital for a fully-outfitted store. Selling on the street is, in many places, a good stepping stone to store ownership. Thus, it’s somewhat ironic that qualities celebrated in the abstract – entrepreneurialism and gumption – are often dealt with rather harshly in real life, particularly when those displaying these qualities are people of colour.

Criminalisation and crackdowns

On New York’s Staten Island in 2014, Eric Garner was approached by officers when they suspected him of selling loose cigarettes; minutes later, he lay dead, asphyxiated. His death – captured in a viral video – galvanised the Black Lives Matter movement. The city has a long and troubling history of draconian enforcement meant to keep hawkers away. In 1988, citing an increase in ‘street impediments’ in areas with high foot traffic, Mayor Ed Koch swept hundreds of vendors from Manhattan’s footpaths which, he declared, “were not supposed to look like a souk”. This helped kick off the city’s war on ‘quality of life’ infractions, most notably graffiti and panhandling, but also previously banal aspects of the streetscape, such as vendors.

Bringing order to New York’s messiness was seen as critical to making it palatable to international investment. David Dinkins, Koch’s successor and the city’s first black mayor, often mentioned that he hawked shopping totes on the streets of Harlem as a kid – his way of illustrating his childhood moxie. Yet, at the behest of bricks-and-mortar businesses, the Dinkins administration passed legislation that cracked down on unlicensed peddling. During this time, the informal economy was largely perceived as a hindrance to ‘liveability’. Street vendors were seen as marginal and insalubrious; often lumped together with Three-card Monte players and the much-vilified squeegee men.

It was during this time that artist David Hammons staged his famous Bliz-aard Ball Sale (1983), setting rows of carefully organised snowballs on a blanket in Astor Place, then a space for the informal sale of books and knick-knacks. The performance turned a common – and ephemeral – material into an objet-d’art. In the years since it has become a legend; while skewering the art market, it also called attention to the position of African American artists working outside of white box galleries. Hammons’ snowball sale anticipated the embrace of informality – in both the art world and the culture at large – as some started to re-evaluate the role of unsanctioned civic life.

A new normal?

As Melbourne sets out on an open-air dining scheme based on New York’s, it would do well to examine the broader history of street use in that city. The six outdoor eating precincts identified by council are promising and will hopefully stick around after Covid-19 is conquered. However, the six areas – located in North Melbourne, Carlton, Kensington, South Yarra and the CBD – are all within the city’s affluent core. One can easily imagine a future scenario where the spillover of eating and drinking onto footpaths is permitted, even encouraged, in the centre, while it’s prohibited in outer suburban areas. This is in keeping with an ongoing trend toward the ‘festivalisation’ of urban spaces, where spaces for cafes and entertainment are often located at refurbished harbourfronts, river walks and squares. These venues are frequently semi-privatised and are patrolled by private security to keep ‘the rabble’ away from diners and pleasure-seekers.

More than nearly any other practice, street vending illuminates the double-morality by which the city’s spaces are allocated and policed. Laneway shops and food halls encourage patrons to wander about with IPAs and roasted corn in hand; while outside, the immigrant entrepreneurs who inspired these spaces are met with harsh enforcement. Criminalising informality is rarely successful, and though laws are needed to protect public health and safety, there should be some amount of flexibility built in.

The opening of footpath cafes may help to reorient shops out of enclosed spaces and onto streets. Spatially, we should look at ways to learn from and adapt the bottom-up tactics of footpath traders and others who have activated and improved public spaces. With time, we may be able to loosen some of the rigidity imposed on the city’s streets, making it a more equal – and more interesting – place to live.