Dreaming up the future of Melbourne’s queer nightlife

It’s not difficult to imagine why those most often at society’s fringe would dream of spaces immune from everyday living. Utopias crop into focus in many queer theories and texts… a paradise, a promised place absent from malice or complication. For many queers, like myself, an extended Melbourne lockdown has us dreaming of sweat and bass; spaces completely antithetical to the shared and collective health of our time. These spaces now feel not only more distant but also more dangerous; vectors for disease and state-sanctioned surveillance. Can you imagine rubbing up against stranger skin? Can you imagine a room steamed with dance? I can barely imagine being outside past eight, or maybe nine.

For many, the queer party is our Utopia. Perhaps this is true now more than ever before.

In 1967 French philosopher Michel Foucault presented a lecture to a group of architects. He invited them to consider ordinary places as something a little more distinctive: “…there are also, probably in every culture, in every civilisation, real places… which are something like counter-sites.” Foucault explained commonplace sites – bars, brothels, Turkish baths, Scandinavian saunas, prisons, cemeteries, museums and even libraries – as “a kind of effectively enacted utopia in which the real sites, all the other real sites that can be found within the culture, are simultaneously represented, contested, and inverted”. He identified these as ‘heterotopias’; spaces within spaces, worlds within worlds, each with their own set of norms, behaviours and expectations.

“A heterotopia emerges from the alternate vision from somewhere else,” says Regan Lynch, “any place where the organisation of things is different from day-to-day life. Social values might be different, the way people behave might be temporarily different.” This way of thinking about space brought Lynch, now completing his PhD at the University of Melbourne, to consider how queer parties participated in world-making by structuring their own set of principles and values. From choosing a venue to booking artists, set design and lighting to marketing and promotions, even the door staff (are they friendly or stern?)… all these deliberations work to shape and govern the queer heterotopias we temporarily wade through each night, which, in turn, creates a relationship with the space.

“I’m looking at how promoters are attempting to create alternative realities and analysing what those alternative visions are,” mentions Lynch, “but also the way those alternative visions are compromised by the material reality of the world… When you have police raiding a place, or surveillance, or someone performing some kind of white supremacist routine incidentally. It’s not like these places are havens from the outside world.”

Some of these compromises or violations are managed internally; promoters are forced to think more critically about their safe space policies, patrons and performers are vetted more scrupulously. But often the real world bleeds into and disrupts our queer heterotopias in ways that can’t be cleaned up neatly.

“How can we radically reimagine our scene and our spaces to better support our communities?”

The rapid creep of gentrification in the inner city has certainly worked to quieten Melbourne’s club scene. Inclining rent prices paired with an over-investment in residential development has positioned partying as less of a cultural oasis and more of an obstacle, a reckless beast blocking a path to greyer, more profitable pastures. In result, queer spaces have seen a pandemic of closures in the last decade. In 2017 Sydney waved goodbye to one of its brightest, Midnight Shift, while a few months earlier Melbourne closed its doors to its biggest, the Greyhound Hotel – a 163-year-old venue demolished in order to be replaced by ‘boutique apartments’.

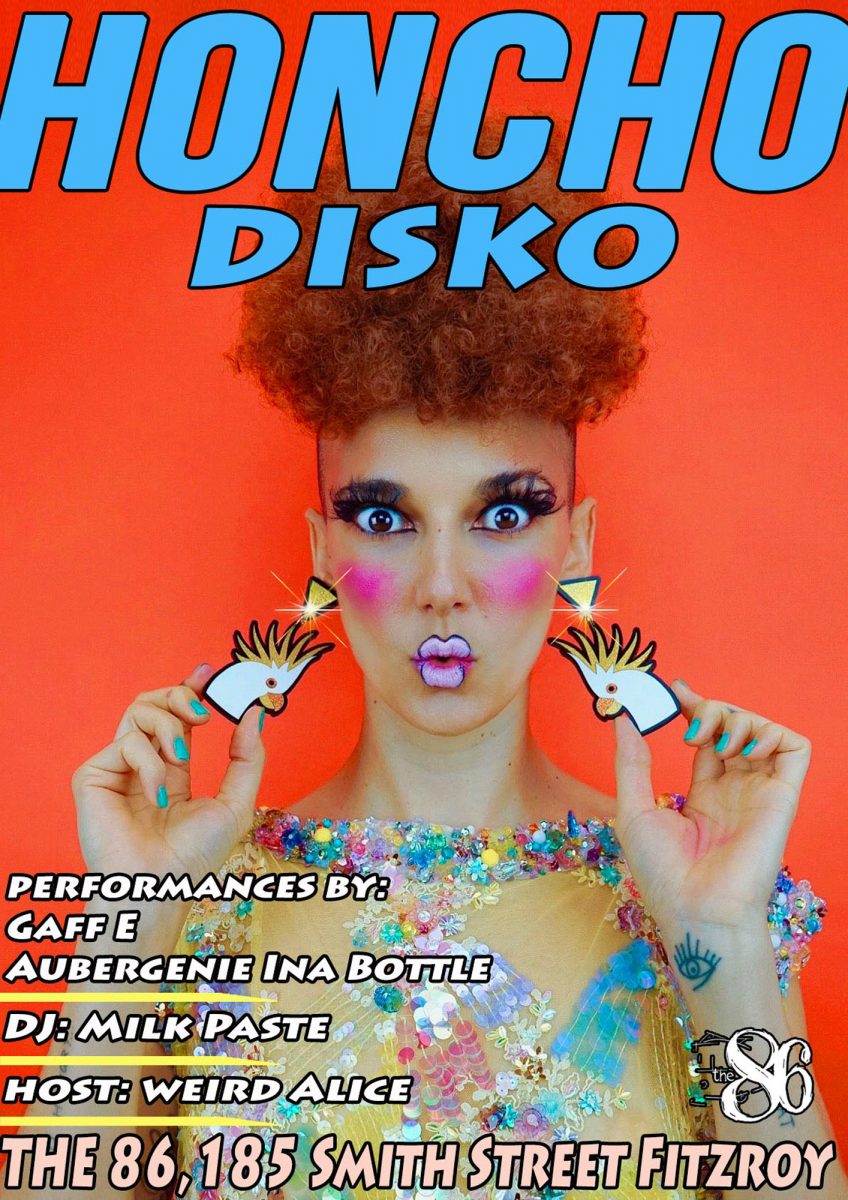

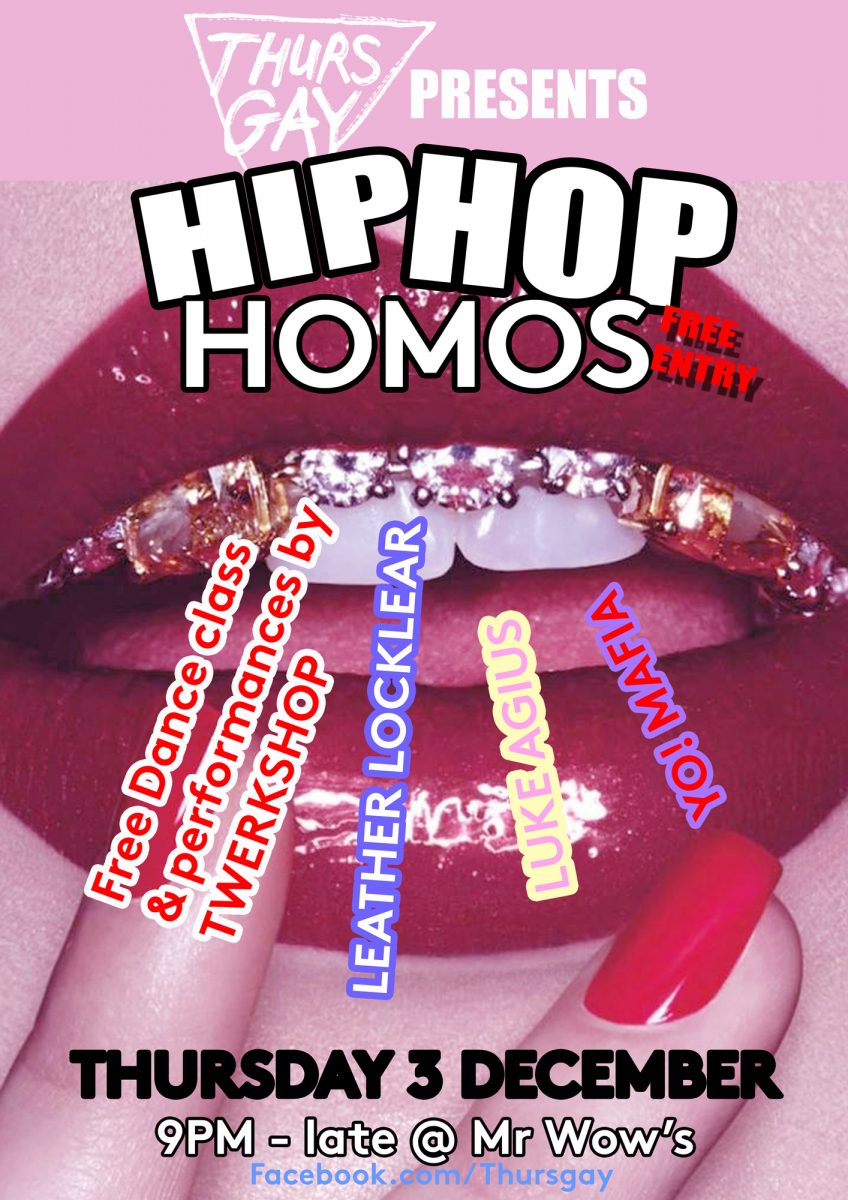

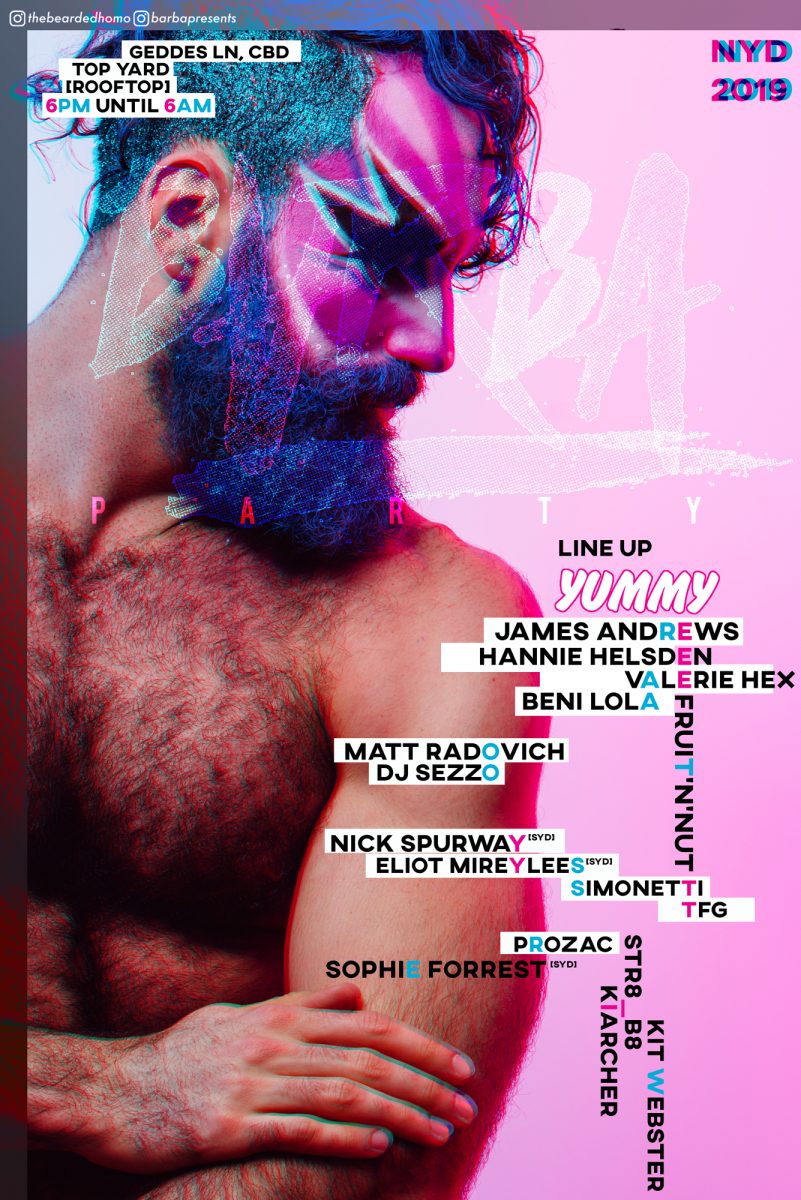

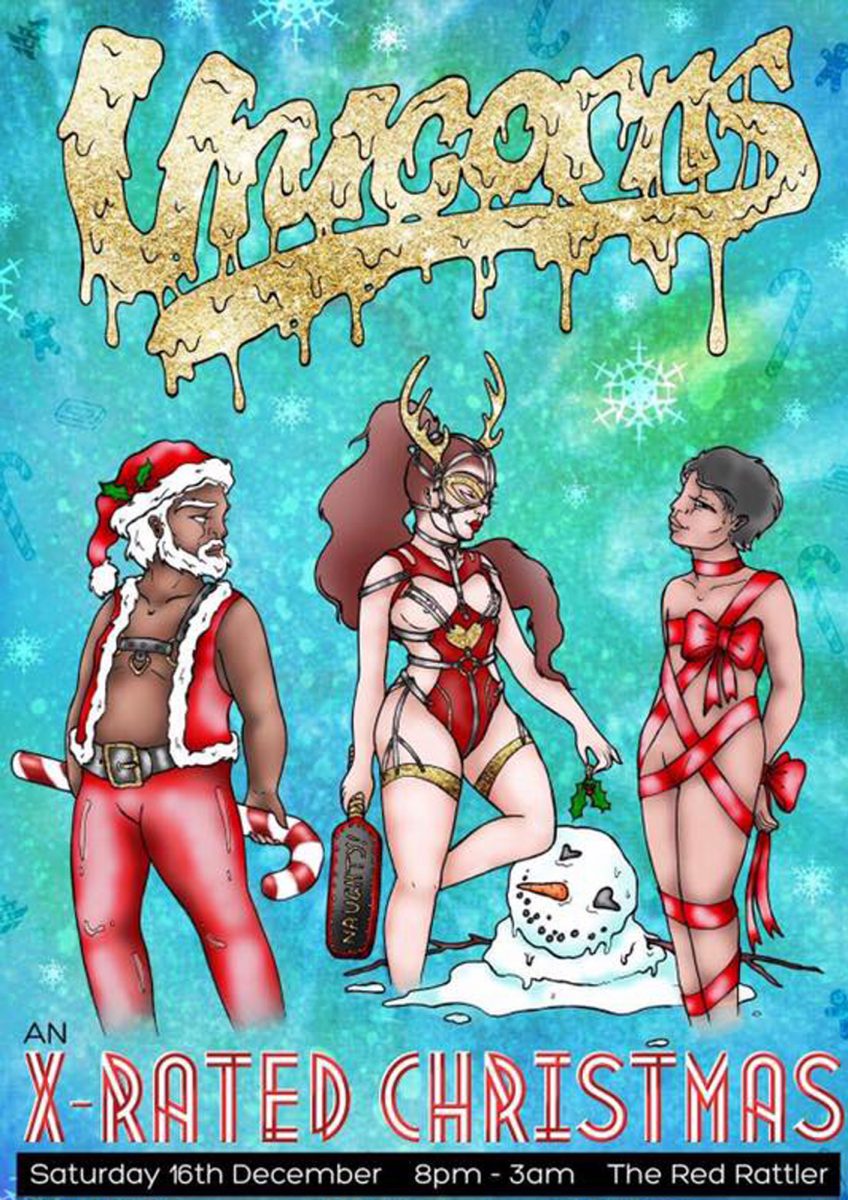

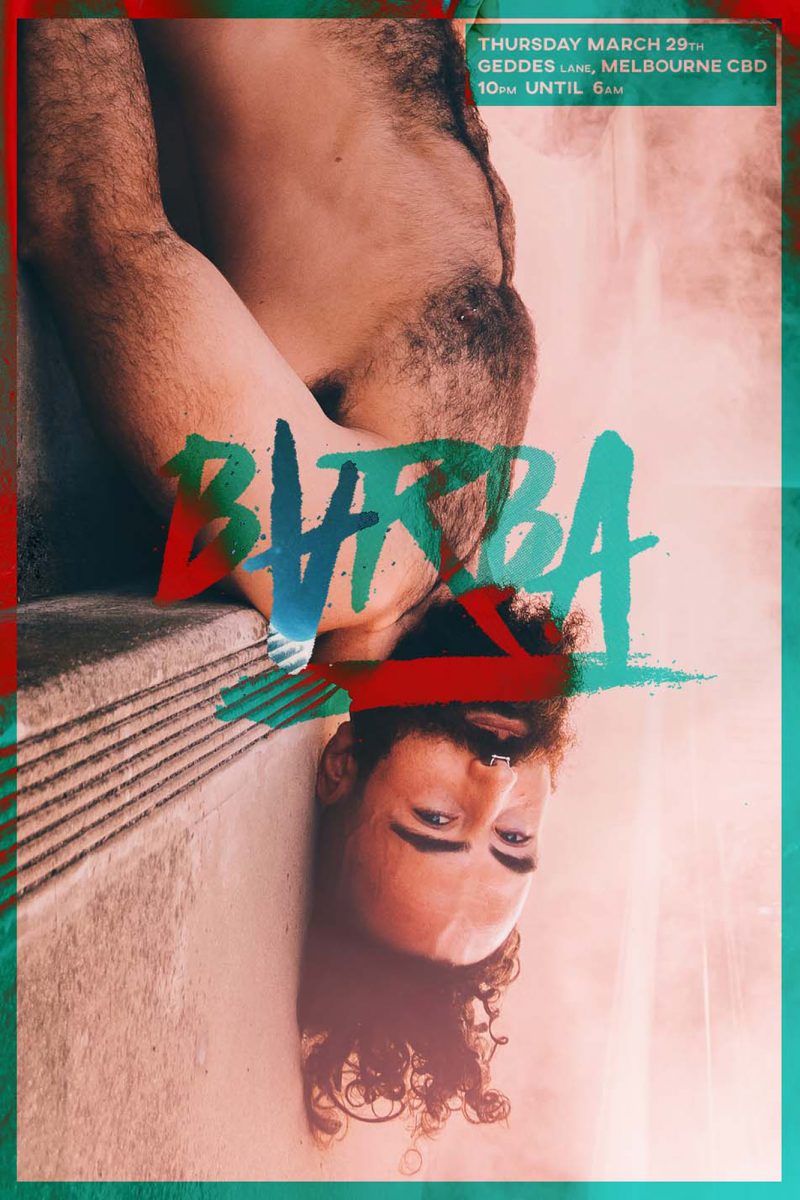

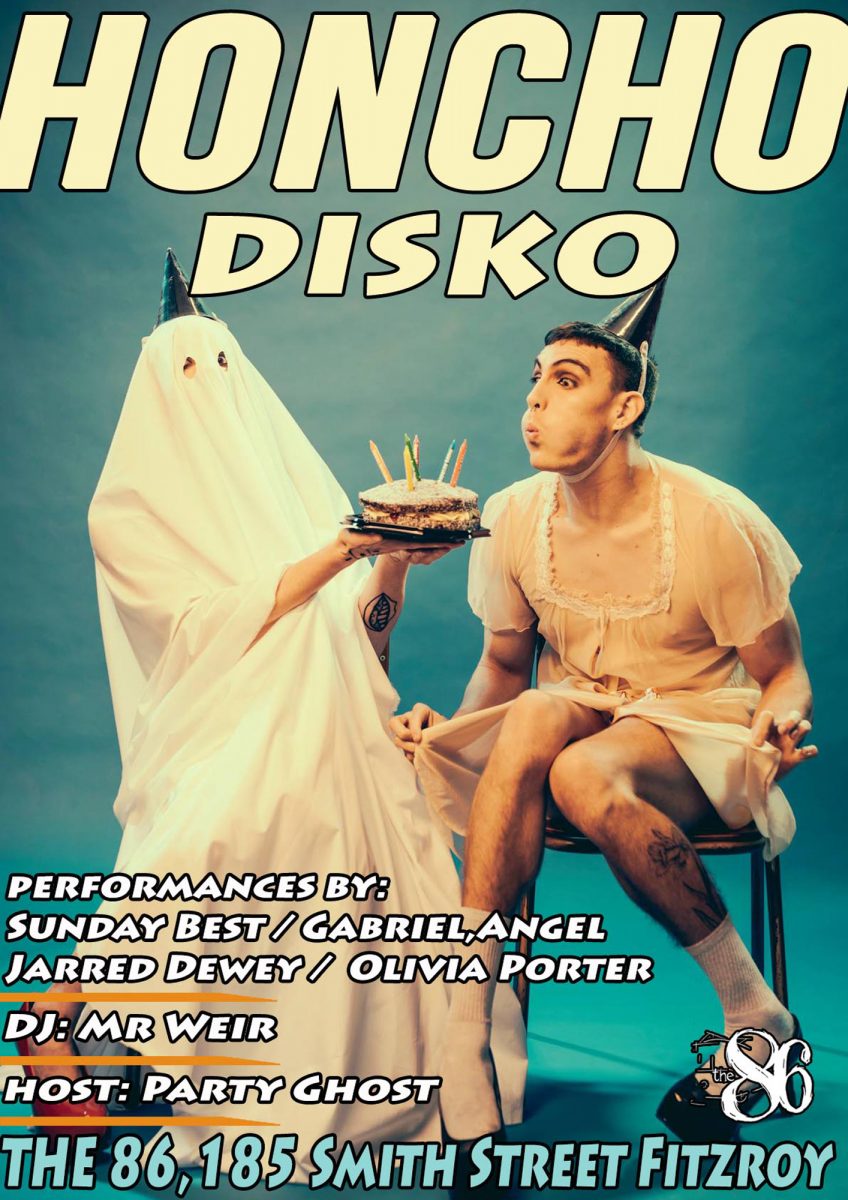

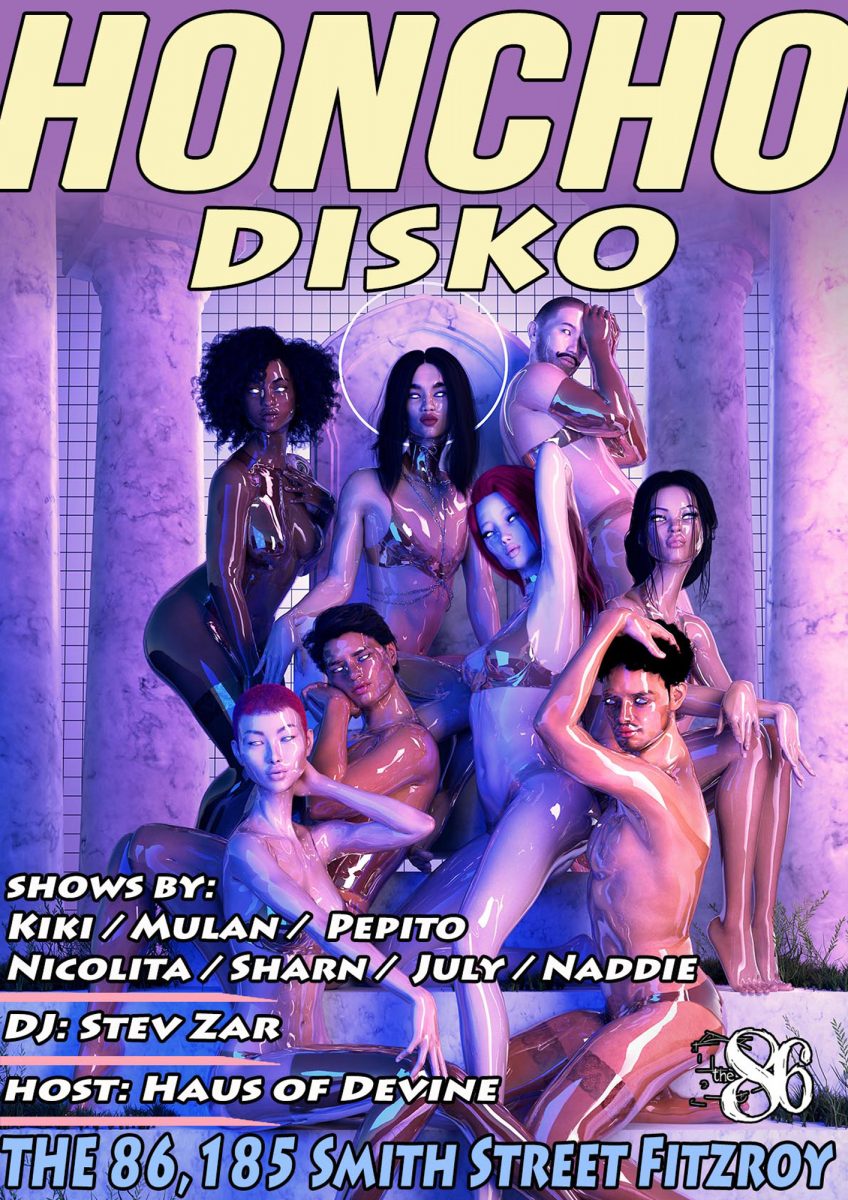

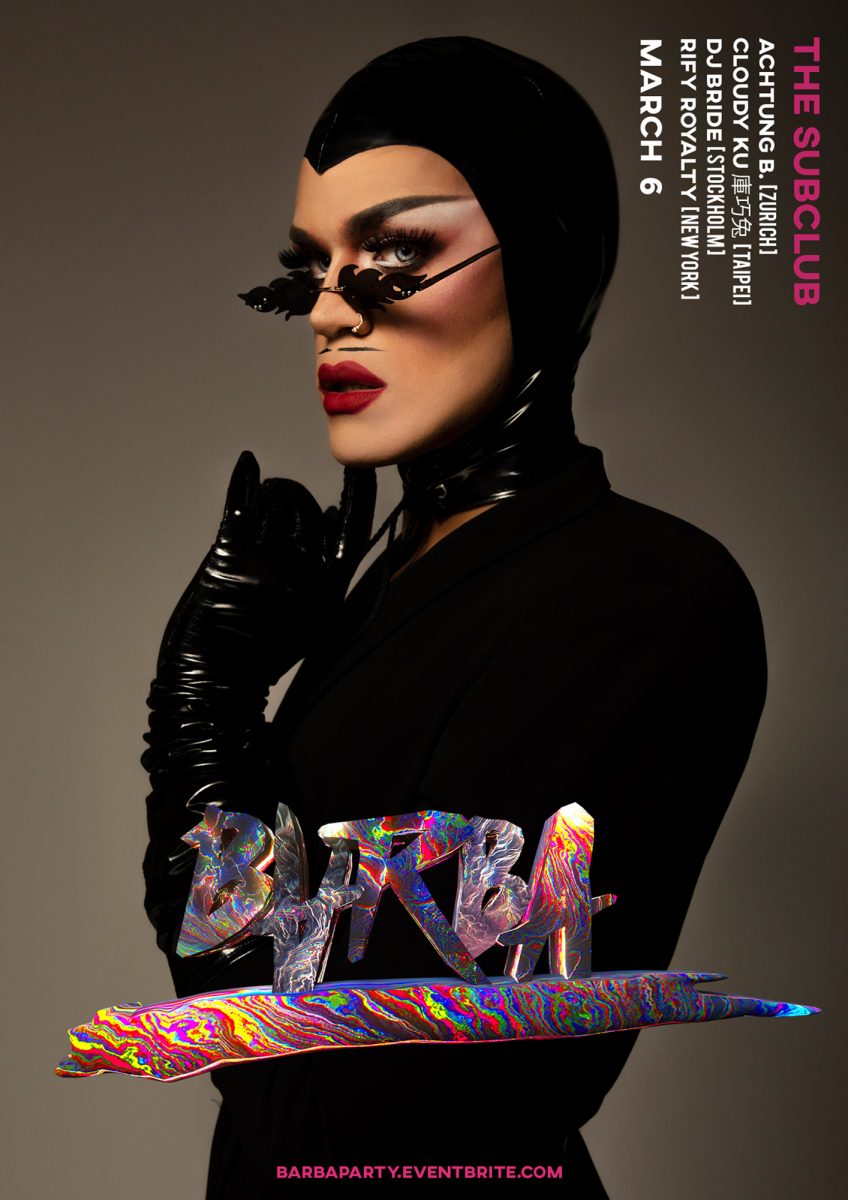

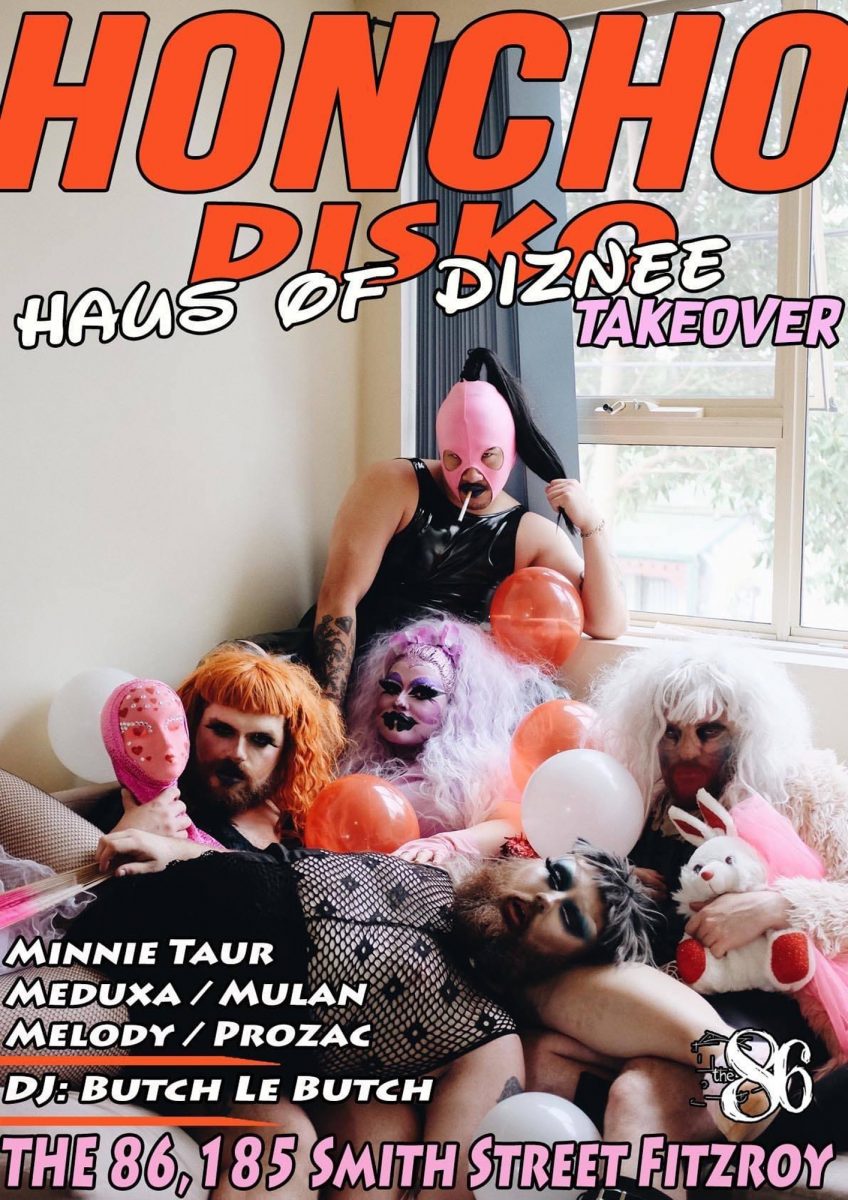

The music doesn’t stop. Queer club culture, now forcibly less reliant on bricks-and-mortar venues, has largely shifted to weekly, monthly or quarterly parties. Nights such as Barba, Unicorns, Tomboy, CLOSET, Thursgay and Honcho Disko practise world-making by catering to the particular needs and desires of their own communities. Some, like Honcho, are a celebration of underground queer fringe performance. Others, such as Tomboy, pull focus to queer women, whose own spaces have faced even greater erasure and sanitisation over the years. Yet all these nights, along with their individual utopian visions, are still beholden to the mores of the broader clubbing scene.

In 2019 Melbourne’s elusive developers took another casualty. “A site that had huge significance to marginalised communities, particularly queer people of colour, was sold to a developer who was a gambling mogul,” Lynch speaks of Hugs & Kisses, a central-city venue that hosted queer parties such as Genki. “Whenever a building is sold to a developer, that licence is gone forever,” he continues.

He aptly describes this process as “a really slow extinction of the 24-hour licences in Melbourne”. Fewer venues obviously means fewer parties, but it also translates into greater restrictions for the types of parties organisers might want to throw.

“In recent years, there has been a freeze in licences past 1am, but that has changed due to the live music lobby.” Lynch explains that while the live music lobby has managed to sell its craft as a cultural staple to community, DJs and club promoters, the parties that dominate queer nightlife have been less successful. Perhaps we need less techno and more organising – or equal fists of each.

But the greatest threat to Melbourne’s club scene has been the emergence and continued incubation of a deadly virus. These spaces, once pillared by human connection, shared oxygen and a pulsing beat, have been hollowed out by restrictions brought on by Covid-19.

Alternatives have sprouted in an attempt to tether community. South-side favourite Poof Doof did a quick pirouette to online, live-streaming its inhouse DJ sets and drag performances each Saturday night. Adele Moleta (aka Delsi Cat) who organises Unicorns – “a space that prioritised and celebrated every human in the LGBTQIA+ spectrum” – funnelled energy into keeping connected by crafting web events around friendship, dating, social support groups and pen-pals.

“I wanted to develop a space where it was not just safe for diverse identities, but a place where we were all celebrated wholeheartedly.”

Still, many recognise online as a temporary fix, a Hello Kitty bandaid over a greater wound. “For moi, clubbing is about being in the room with others,” says Meaghan Palmer, co-founder of Thursgay, an inclusive queer weekly party run out of Yah Yah’s on Smith Street. “I miss dancing to Rihanna while surrounded by heaving bodies, regrettably downing too many Jäger shots and meeting new best friends in the bathroom line,” reflects Tali Polichtuk, Thursgay’s other mum. The pair birthed Thursgay seven years ago when options for queer clubbing were much more slim (particularly for non-gay men) and venue acquisition was an uphill battle. “Even a couple of years ago, Thursgay was at a venue that would not promote our presence there, despite being their biggest earner,” says Polichtuk.

A few blocks north lives Honcho Disko, a Thursday discotheque for “the creative creatures of the night”. John Pants, Honcho’s organiser, is preparing his dance back into society. “There will have to be table service for drinks and food, with people not being able to mingle as much… The important thing is to rebuild these venues and spaces, so starting small and being able to offer any type of nightlife entertainment is a win.” Renée Russo, founder of Tomboy, a monthly day-into-night party for queer women and their mates, is thinking outside the confines of interior space altogether. An outdoor day festival – in complete compliance with the regulation of the minute, of course – is slated for the new year. What everyone agrees on is that additional funding is needed for these ventures to survive. Grants can be complicated, particularly when ‘partying’ can’t be so easily squeezed into a state-operationalised rubric (an allegory for the wider queer experience).

But lockdowns have also allowed time for deeper reflection. How can we radically reimagine our scene and our spaces to better support our communities? “I think it’s helped people learn about accessibility, which I’m always excited to hear people discuss,” says Delsi, whose Unicorns parties have accessibility and inclusion baked into planning. “I wanted to develop a space where it was not just safe for diverse identities, but a place where we were all celebrated wholeheartedly.” With lockdown forcing us to continually rethink space, bodies and their perpetual dance, perhaps it’s a prime opportunity to prioritise accessibility in the making of our heterotopias.

“Queer party spaces have always been really important spaces during crises,” offers Lynch. This is true. Our yearly celebration of Pride reminds us that our ongoing path to liberation is hard-fought: it was the dancefloor that became battleground during the Stonewall Riots of 1969. Closer to home, Melbourne’s Tasty nightclub police raid of 1994 saw its queer patrons detained, stripped and cavity-searched for hours on end – our sexuality, policed and politicised, on home turf. The battle for 2017’s ‘Yes’ vote also activated queer spaces into sites of political organising and consciousness raising, in addition to providing much-needed community support during a time of deep heartache.

Let’s never forget the AIDS crisis of the 1980s and ’90s. The dancefloor – a simultaneous site of joy, resistance, liberation and celebration – plays wake to generations of gay men, a memorial for their chosen families; a virus pulling a community together under tragic circumstances. In 2020, our enemies look strikingly different and strikingly similar, but our parties hold utopian visions for a thriving future. Our spaces remain anchors to our history; transformative sites that, in turn, transform to our common needs – only this time, it’s our turn to fight for them.