Feminism, gardening and extinction with Janet Laurence

Over 30 years, artist Janet Laurence‘s installations have explored the interconnectedness of all living things: minerals, animals, us. A deeply ecological sensibility permeates her work, which sits between sculpture, architecture and environment. With her first major survey exhibition now on at Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney, Rafaela Pandolfini visits Janet’s studio to talk feminism, gardening and extinction.

Upon arrival at Janet Laurence’s studio warehouse in Chippendale, Muddy, her dog and studio companion, welcomes me with a lick. Janet is finishing off emails to the staff at MCA regarding her new major exhibition, After Nature, part-retrospective and part-new installation titled Theatre of the Trees.

The show includes living plants, and so the issues arising – now that the exhibition is open – are somewhat unusual for a gallery context. “They are an amazingly professional team at the MCA,” Janet explains. In general, she has to attend the show and train the invigilators regarding exhibition upkeep. The MCA has low light levels in the first room: “It is always a difficulty with live plants.”

In approaching this interview, I was thinking about how rare this opportunity is, for an artist to talk to someone who has had such a long and successful (and continuing) career; and how these conversations should occur more often. I am inspired by Janet starting her career in an era when art was so male-dominated. In the foreword to the large colour publication accompanying the exhibition, Rachel Kent introduces the key works and themes across Janet’s impressive thirty-year career:

“Empathy lies at the core of Laurence’s multi-dimensional practice, expressed in her concern for, and nurture of, the fragile objects and creatures within the works. It also reflects her desire that we – as viewers, and human beings sharing the planet with other species – identify with and care for them as well. In this regard her work speaks to essential questions around reciprocity, understanding and co-existence: the fundamentals of survival and growth in a perilous age.”

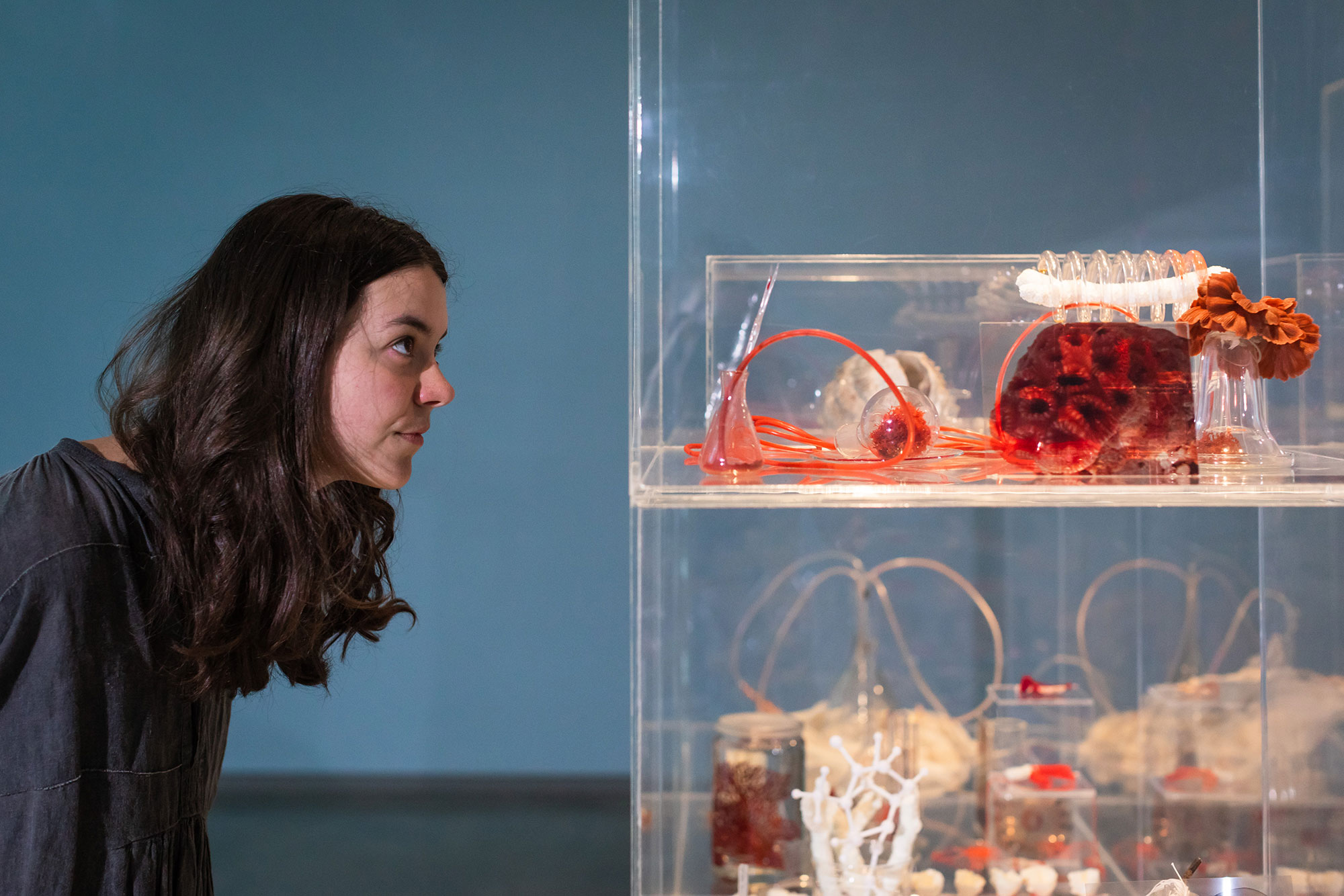

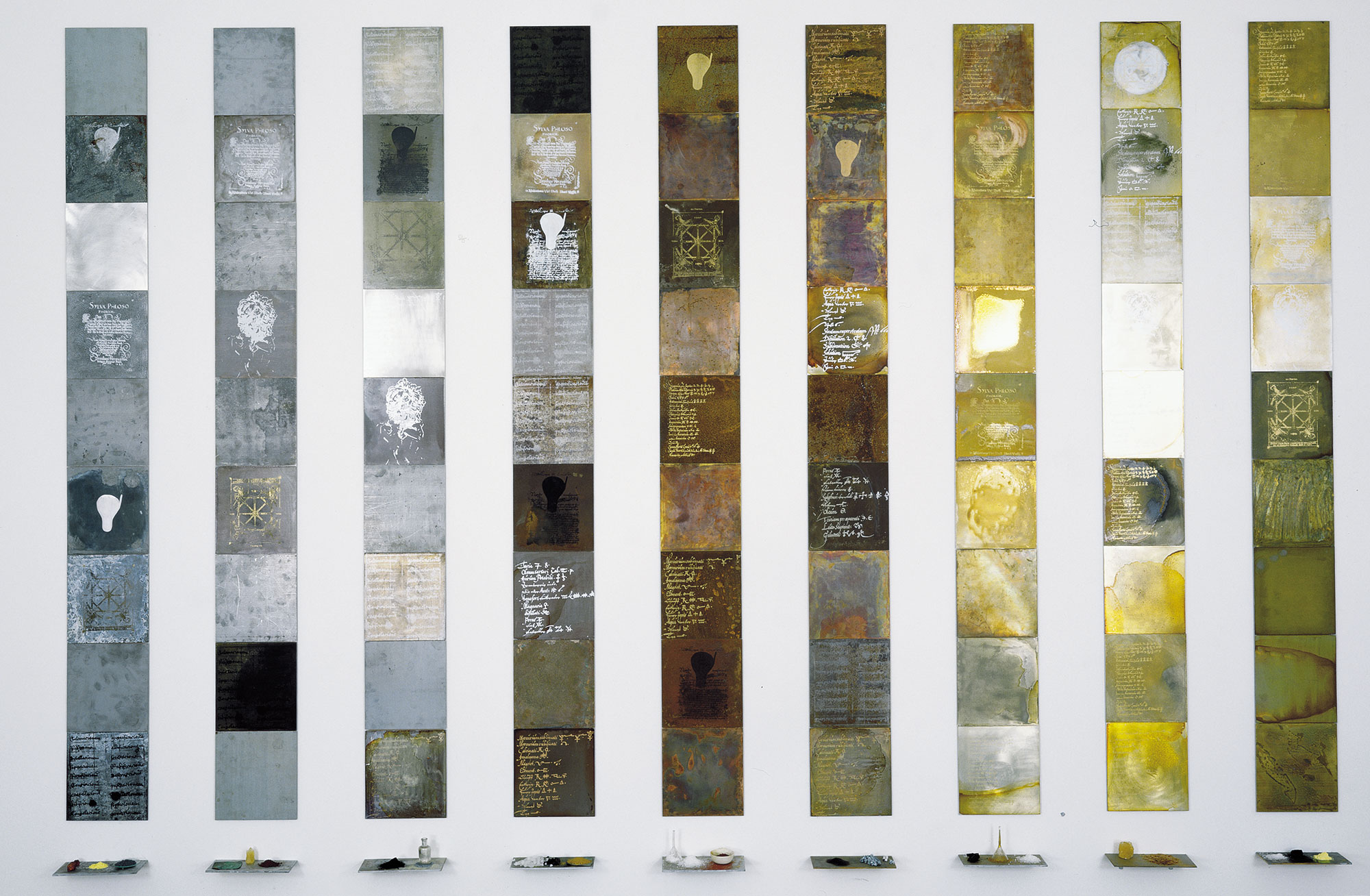

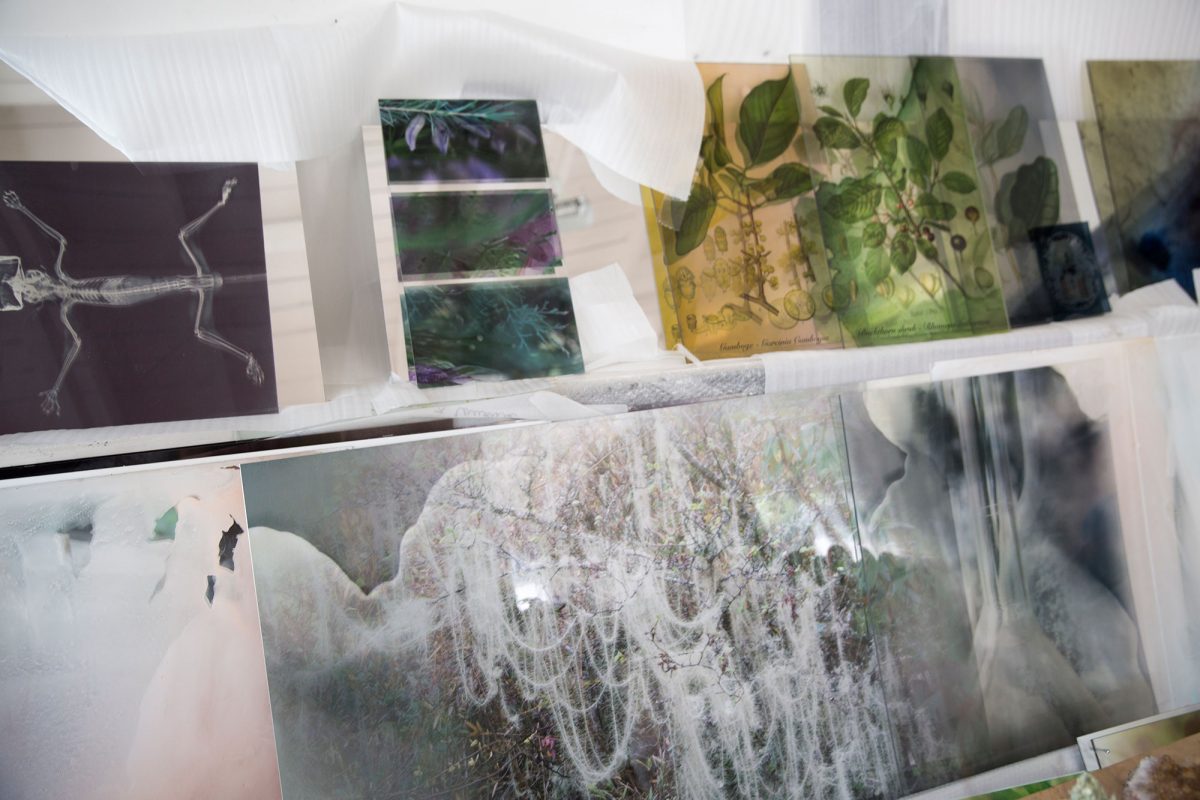

After stepping off the busy Sydney city streets full of construction, After Nature is a peaceful relief, immediately transporting. It is a truly immersive experience, including Janet’s signature sheer white material alongside collected artefacts, video and sound works, and plant life installations kept alive in vials of water. While it is all delicate, the show forcibly brings nature to your attention.

In the exhibition catalogue, Rachel Kent suggests that the intention with Janet’s work is to constantly ask the questions “how can we help others to help ourselves? How can we work together to save our planet for future generations? Bridging ethical and environmental concerns, Laurence’s art reflects on the inseparability of all things and represents, in her words, ‘an ecological quest’.”

Rafaela Pandolfini

You express the hope that viewers will have a take-away from experiencing shows with a message. Do you have any examples of audience feedback?

Janet Laurence

Always. After my last exhibition at Sherman Foundation [After Eden, 2012], which was all about lost habitats, I was told that there was an increase in viewers connecting to conservation foundations as a result of seeing the show.

RP In the exhibition catalogue, images of your garden at home jump out at me. As a lot of your work is about conservation, it is natural that there is a plan in place for the contents of your exhibitions after they close. Do the plants all go into your garden at home? What happens to them after the shows?

JL Not all of them. For example, the plant hospital works which died and were preserved with shellac ended up in the collection of Art Gallery of New South Wales. And I also always have extra plants at my studio for the vials.

I started my garden 15 years ago. It is actually public land, an abandoned area that was thought to be toxic, but the plants have taken off there. As we know, plants absorb the toxins. It has just been gradually repopulated by native plants. It has its own ecosystem now, owls, lizards and bats. Down the bottom there are a lot of edible native plants. And some citrus and pomegranate and melaleuca sand banksias. It’s wild, but also controlled, I garden it a bit, controlling weeds.

RP I am interested in the artists you studied with, your peers, and whether they are still part of your community?

JL When I came back to Australia after studying Arte Povera in Italy, I had John Olsen as a teacher. His philosophy, a zen philosophy with the landscape, was about becoming it yourself. And I used to go on great nature walks, so that time was very influential.

But this was very different to what the art school was teaching at that time, which was more abstract expressionism. I kind of went along with that, because I was in the painting department. But I was making all these other configurations at the time – Australian artists influencing me at that time were Rosalie Gascoigne and Marr Grounds, but really there were very few artists that I was interested in. I certainly wasn’t interested in my lecturers. (Bronwyn Oliver, Robert Owen, Joan Brassil and Joan Grounds, wonderful figures to respond to in my postgraduate studies. I preferred the art theory side of things at university.)

RP Do you collaborate with younger artists? Do you think that it is important to be connected to younger generations of artists?

JL Not really ‘collaborate’; it is more that I work with other artists in different fields to create my works. Gary Warner does the video-technical side, and the soundtracks come from a friend of mine, Jane Ulman. She used to produce sound programs for the ABC, and specialises in bird sounds – she has a whole library of them. But rather than visual arts, it’s the scientists I connect to. I connect with environmental groups – everyone mingling together in that concern. And I work a lot with architects who are in my studio space, as they have the skills to map shows out.

RP Nina Miall’s final essay in the catalogue for After Nature, ‘The Constant Gardener, On Janet Lawrence’s Site Specific Works’, brings up the idea of the care and a feminine connection in your work. This feels like a much different perspective to the other writers. Do you see this as an important aspect of the work?

JL Femininity and care is more apparent in my public works; also, historically, in wanting to make work with landscape, rather than make big monumental structures like men have traditionally. The installation I made in Homebush Bay, In the shadow (2000), was often referred to as ‘lingerie works’ – I think that the mist alluded to that. But persistent in my work is the veiling, and layering transparency into translucency. Ways of seeing into things. That seduction of the veil could be seen as feminine.

RP Are you aligned with any political parties that aligns with your work?

JL Yes. I support the Greens and I support Get Up, Australian Wilderness society and Greenpeace. I have got material from them which you can see in the exhibition installation at MCA.

RP A lot of your work talks about a connection to the land, in Australia, but also in other countries that you visit. I wondered whether you work with Indigenous or First Nations people when creating your works about preservation of the environment?

JL With Edge of the Trees (1995) I worked with Fiona Foley on the Eora aspect of the show. I wanted the work to be about reconciliation, which was perhaps a bit ambitious. I have done that in Mexico: developing work with the Indigenous people, but not making completed works together. Just trying to learn from them and about their situation with the land clearing there; but never specifically creating art work together.

Looking over Janet’s oeuvre, I have a persistent feeling that her quest could continue in consultation with Australia’s First Nations people, who understand better than anyone the devastating destruction colonialism has had on the environment. They also understand about nurturing the environment, and passing the knowledge onto younger generations. In the words of Professor Jackelin Troy, who urges us to learn the Indigenous names for Australian flora, “from Australia to the Andes, indigenous peoples understand that trees sustain us and are part of our human world…when we destroy trees, we destroy ourselves.”

It is a great privilege to peek behind the scenes of a leading Australian artist – thank you, Janet, for the invitation. After Nature is on at Sydney’s MCA until 10 June. You can also dive deep into Janet’s work on her website.