Laura Castagnini and Megan Wong on finding solidarity in London

Australians Laura Castagnini and Megan Wong moved to London four years ago to pursue their passions: contemporary art and political activism. Between feminist art history and human rights law, this is a couple whose shared life is dedicated to shifting culture. We visit their home in Camberwell, close to radical art spaces, farmers’ markets and tiny green parks.

Australians Laura Castagnini and Megan Wong always wanted to live overseas. So when Castagnini got a job at Frieze magazine, they took the plunge. Now, for almost four years, they have been living in London, surrounded by art, food and community.

Their estate block is above a tiny green park in Camberwell, with a (very affordable) farmers’ market on Saturdays. Important radical spaces like the Black Cultural Archives, 198 Contemporary Arts & Learning, and Arcadia Missa are a 10-minute bike ride away in neighbouring Peckham and Brixton; closer to home is South London Gallery.

Castagnini now works as assistant curator of modern and contemporary British art at Tate, where she assisted on the current exhibition All too Human: Bacon Freud and a Century of Painting Life and is now working towards a forthcoming Frank Bowling retrospective. It’s a full-time job she occasionally combines with freelance writing and curatorial projects in Australia and the UK (she recently curated a film program and wrote a catalogue essay for the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art’s Unfinished Business, a survey of contemporary feminist Australian art; while contributing to a catalogue for The Place is Here, a touring exhibition on black British art of the 1980s). Wong is studying a masters degree in human rights law while working part-time in the NGO sector. She recently worked with an organisation campaigning for the rights of migrants in the UK. She says, “Within my role, I worked on a project that explored what makes migrants vulnerable to issues such as homelessness and labour exploitation. Through interviews with migrants, my research highlighted the link between immigration status, homelessness, destitution and exploitation, as well as the impact of the UK’s draconian immigration policies on migrants’ lives.”

This is a couple whose shared life is dedicated to shifting culture. We visit Castagnini and Wong’s home in Camberwell.

Laura: I met Megan on Halloween in 2009. I spotted a girl at a house party with the most incredible costume, a sanitary napkin! Megan made it from a mattress protector and covered herself in blood. It was disgusting and feminist and hilarious all at once. I was so impressed that I just had to talk to her. It was love at first sight.

The art scene and employment prospects drew me to London. Although it’s a very competitive job market, what makes me stay is that no matter how niche your interest – in my case, queer, feminist and decolonial art practices, specifically video and performance – there will be a ton of people who are also into it and a million events to attend. I’ve found a sense of solidarity here.

For those whose identities fall into the categories of ‘minorities’, the personal has to be political, but I would also hope that my politics can extend outside the limits of my personal experience. I am lucky to have a lot of mentors and colleagues in London – when I first moved here, I joined a monthly feminist art reading group run by the wonderful feminist curator Helena Reckitt, where I met lots of artists and curators. We read non-Anglo-Euro/American feminist texts and often go to the pub afterwards. I worked for two years at Iniva (Institute for International Visual Artists) where I learnt an incredible amount from collaborators such as Sonia Boyce and David Dibosa, co-investigators in the Black Artists and Modernism research project, who continue to inspire my thinking about race and representation in the UK. At Tate I work every day with Elena Crippa, from whom I am learning how to practise feminism and to challenge white-dominated art histories from within the institution itself.

I do, of course, miss dearly my artistic community in Melbourne – especially the artists whose work I followed for years, and mentors like Vikki McInnes, whose support has been unwavering since I left. She was actually the one who said to me, “I think you should go and live in London for a couple of years, it’ll do you good.” She was right!

Depending on the project I am working on, my days at Tate can be filled with any-thing from exhibition tasks like research, loans, paperwork or writing, to meeting artists or collectors, to giving curator tours in the gallery. I usually finish by 6pm. Sometimes I’ll go to art events like exhibition private views or lectures after work, but other nights I’ll cycle home and go to the pool or cook dinner. To be honest, I cook very rarely because Megan is an incredible cook, she is obsessed with food and whips up the most delicious meals without a flinch. We usually eat dinner together, then I’ll clean up and have an hour or two to relax before going to bed around 11 or 12.

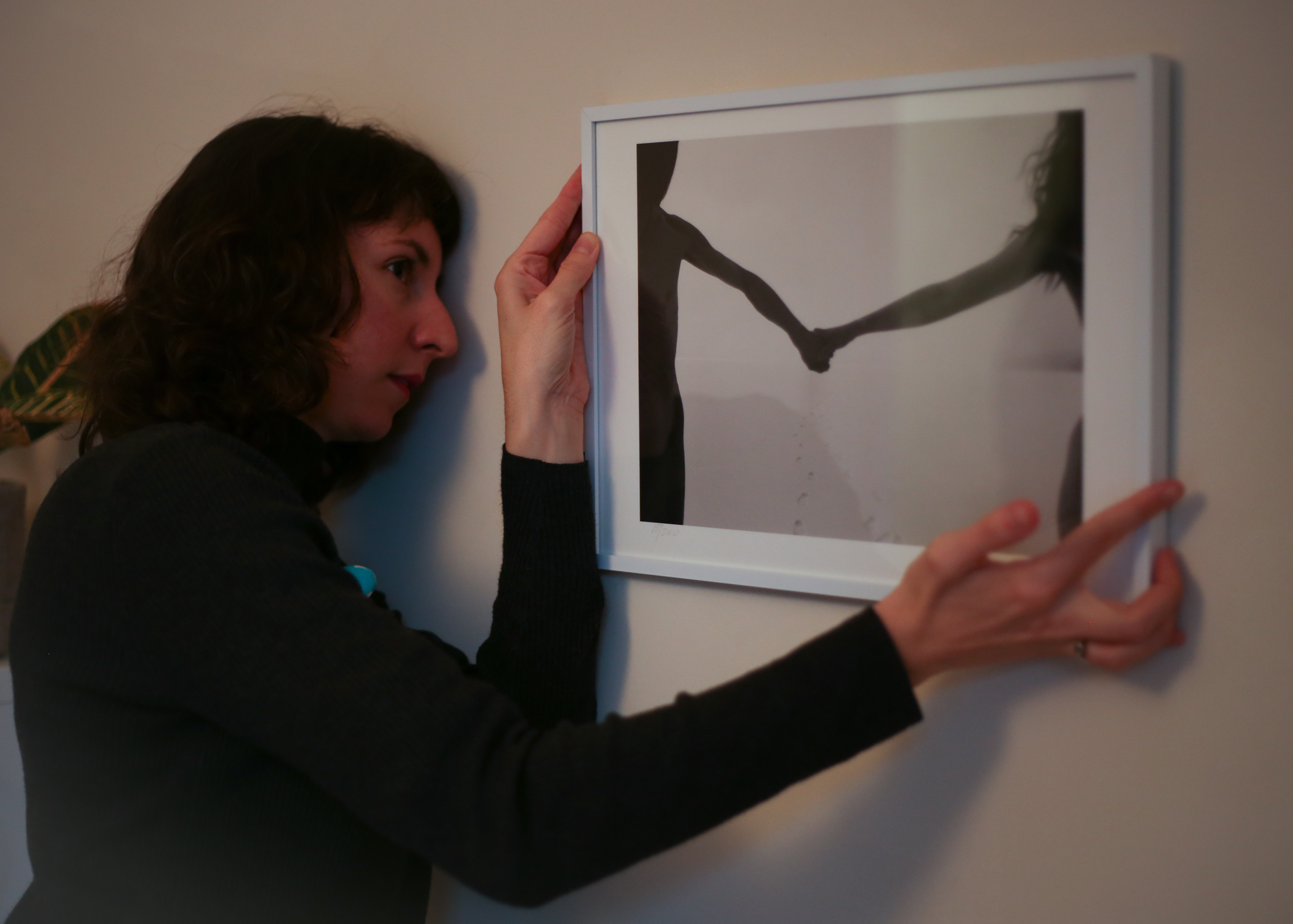

I would say that our aesthetic hasn’t changed much from past homes. For me, the objects of significance are mostly artworks – seeing them every day gives me strength to carry on in my work. Curators get paid peanuts, so I don’t really have the money to buy artworks outright, but I am very lucky to have been gifted some beautiful images from women artists who I have worked with in the past or simply gushed over during a studio visit. I was recently given a pair of amazing prints by the artist Chila Kumari Burman of her Autoportraits series: stunning, photographic collages of the artist in various Western and Indian guises. We also have an Alice Lang Original prominently displayed: a boob mug made from a scaled down 3D body scan of the artist Alice Lang. I worked with Alice on these for the exhibition Curating Feminisms in Sydney, in which 30 Alice Lang Original mugs were fabricated, packaged and mailed as unsolicited ‘gifts’ to admired curators, gallerists and critics – awkwardly transforming the gift into a vessel for artist self-promotion that parodies the objectification, dissemination and consumption of anonymous women’s bodies. Other valuable objects in the house are simply reproduced images of artists that I admire and that remind me of projects I am proud to have curated, like various images of Salote Tawale’s scattered around the house (and also in my office). We arrived in London with basically nothing, so it’s taken a while to accumulate these powerful images that line our walls. They are like souvenirs, or talismans.

I know this is a bit cheesy, but the other valuable objects are gifts from Megan – she’s made some lovely collages, poems and pottery for me over the years.

Megan: We have a RongRong & inri artwork hanging above our bed, which Laura gifted me on my 30th birthday. I grew up in China during high school. Before 798 Art District became really commercial, we used to go to underground gigs in some of the unused factory spaces. There were only a few galleries in the district back then, and it was during this time I came across RongRong & inri’s photography. I’m a romantic at heart and had just started developing my own photos, so I was immediately drawn to the black and white images RongRong & inri had taken naked in the snow. I took home free postcards of their work. Later, going back to China in 2010, I bought a book of their photography with the hope that one day I’d have one of their artworks. This gift from Laura was really special and I appreciated the lengths she went to to get it for me!

My cookbooks are also of great significance – they’re the only books I brought over from Melbourne. London homes are tiny!

Coming from Australia, we still haven’t got used to living in small spaces and really miss gardens and being able to have more than three people over for dinner (we only have five chairs!). We’re starting to get better at being minimalist, and now it feels easier to make a small space homely.

Living in a block of flats makes you appreciate outside shared spaces more. We are surrounded by parks that have tennis courts and outdoor gyms so, when it’s warm, we go outside to be among fellow Londoners. In the morning, I try to wake up with a little cheer by doing a dance, stretching, or singing my old favourite, Life by Des’ree. I then proceed to bounce around on the bed to wake Laura up, get dressed and make breakfast. Usually by this time, I’m in a rush, so I quickly eat and jump on my bike to uni or the hour-long cycle to work. I love cycling in the morning because it gets my brain going. The ride over Waterloo Bridge gets me every time. I always wonder: How do I live in this amazing city? At work, I could be doing desk-based research and report-writing, meeting people from the sector or doing interviews with migrants about their life in the UK. At lunch time, I might go for a walk with a few colleagues to Hampstead Heath, where we admire London’s skyline. At the end of the day, I usually cycle home and cook something delicious followed by a bit of study or some exercise. On some evenings, I head to uni for a tutorial, or I do something to care for myself, such as going to improvisation dance classes.

It has taken some time, but we do have a good bunch of people in our lives in London: friends I met through work and university, but also some old friends I went to high school with in China, and friends we’ve met through friends! Our friends here always amaze me: they continue to involve themselves in activism, work, their art practice, or running film festivals – this also means it’s always difficult to catch up! Of course, I miss my friends and old colleagues back in Melbourne, and think of them often. I definitely look up to my old colleagues at the Multicultural Centre for Women’s Health in Melbourne who do amazing work and have been influential feminists in my life.

Thank you, Laura and Megan, for letting us into your home. You can find more of Laura’s work on her website. Thanks also to Alex Lama for his wonderful photography. This is an updated version of an article which was originally published in AP#9: ‘Radical Family’.