Arts Project Australia advocates for inclusion in the contemporary art world

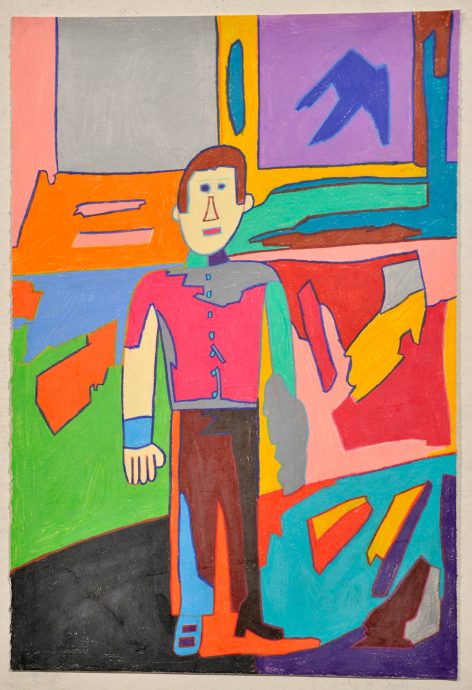

Since 1974, not-for-profit organisation Arts Project Australia (APA) has been championing the talents and wellbeing of artists with an intellectual disability through its open philosophy of agency, freedom and collaboration through art. Founded by Myra Hilgendorf OAM, APA now provides over 100 artists with space to work and quality materials, professional guidance, artistic mentorship, and, through its gallery and strong exhibitions programme, a means to exhibit and sell work. Since the beginning, and even more so in recent years, APA has developed an engaged dialogue between its artists and the wider community. Studio artists are consistently represented in ‘mainstream’ exhibitions and events – testament to the organisation’s hard work in forging space, respect and visibility for its artists within the broad spectrum of contemporary art – and within greater society itself. On a wintry Thursday, Grace McQuilten visited Arts Project HQ (Assemble’s Northcote neighbours) to speak with Executive Director, Sue Roff.

Grace McQuilten

One of the first times I heard about Arts Project Australia (APA) was while talking with Kirrily Hammond [a Melbourne-based artist/curator] about art and life. She started telling me about this great organisation and interesting artist collaborations APA was doing with contemporary artists. In our whole conversation, the word disability didn’t come up once.

Sue Roff

Yay! That’s what I’m talking about!

GM I thought it would be really nice to hear from you about the way in which APA positions itself in the art and wider world…

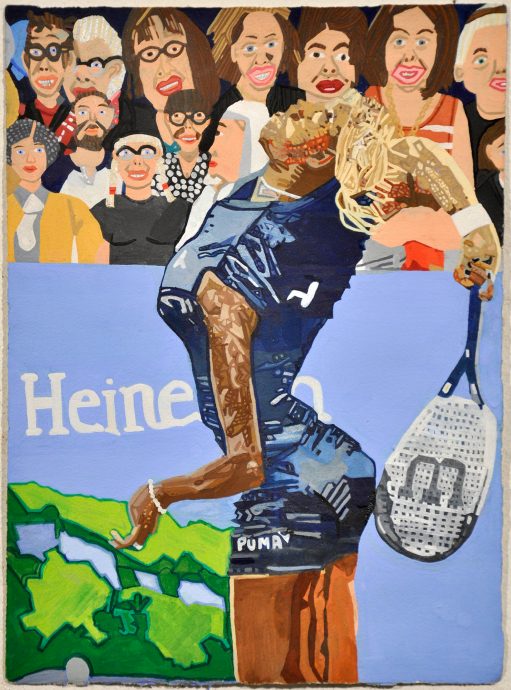

SR We don’t use the word ‘disability’ where we can possibly help it, because we don’t believe that it assists, and we’re not rights activists in that respect. We feel that people with intellectual disability probably have some of the roughest trots in life because they generally don’t manage their own affairs or their own money. Even though they have a lot more freedoms and choice compared to 30-40 years ago, at the end of the day, someone with an intellectual disability is going to be taken a lot less seriously than someone that is not able-bodied but has a perfectly functioning brain. So we try not to use the word ‘disability’ because to many people it still conjures up the ‘sheltered workshop’ aspect. For instance, at the Melbourne Art Fair where we have a stand, it’s not mentioned. At the end of the day, we just think that art is art, however it’s created. There is some fabulous art created here – does it actually matter that someone has autism or Down Syndrome or an acquired brain injury? It might be part of an interesting story, but the art should represent itself. We don’t deny it, but we don’t make it the selling point – we’d never want to call this ‘disability art’. That’s the attitude we come from, which is possibly a little different to some of the more activist-based disability organisations.

GM Is there a danger that the stigma associated with the idea of disability in the mainstream community could filter or influence the way people see the work, rather than appreciating it for what it is, first and foremost?

SR Yes, and there are many false assumptions that people make about different forms of disability, like ‘everyone with Down Syndrome is happy’, and ‘everyone with autism is an expert on something’… I mean they are really broad generalisations. They’re not necessarily true for every individual.

GM APA seems to break down the barrier between centre and periphery. You connect the wider contemporary arts scene with your studio artists. Do you see this as a two-way benefit, not just for the studio artists you work with, but for the wider community as well?

SR Advocacy for inclusion of our artists’ work within contemporary art practice is actually a part of our mission, so we see the collaborations and projects between our artists, and artists and curators from other places as integral to this. Not only do the external practitioners get to work closely with our artists, they also develop a better understanding of the nature of intellectual disability, and how art crosses all boundaries. One of the comments we hear most frequently from trained artists is how ‘free’ much of the work created in the Arts Project is, and how they would love to find their way back to that freedom.

GM What does an average day here look like?

SR 45 artists converge in the morning in a cavalcade of cars, taxis, trams and buses. The gallery is full of chatter and news for a while. At 9.30am, they head up to the studio to start work for the day. Some may go out for a field trip to a gallery or an artist studio, but mostly everyone works on their own artwork, which could be painting, drawing, ceramics, digital media, printmaking, 3D sculpture, and even textiles. We often receive a visit from external artists and curators who may be thinking of working with us, a regular group of visitors to see the latest exhibition in the gallery. It’s a lively busy place until around 3pm, when the artists go home, and the staff clean up and get things organised for the next day.

GM You’ve worked with a lot of really well known artists and curators on many exciting projects and collaborations. Can you give me some highlights?

SR We’ve certainly had some fabulous curators, Kirrily Hammond being one of them. We invite them in and they go through our stockroom, and look at the work and come up with a context and then exhibit our artists’ work alongside the work of other artists. So it’s connected to the broader art world. Kirrily, and more recently Karra Rees, are two people who have really immersed themselves in the organisation, and it’s been fantastic. In terms of the artist collaborations, we’ve orchestrated a lot of them… some have worked brilliantly and some didn’t work so well, but that’s just how it goes.

I love the flow on effect. We’ve now got two emerging curators through the Next Wave Festival organising a group project. Also, Charlie Sofo (a Gertrude Contemporary artist who was introduced to us) and one of our artists, Mark Smith, have developed a collaborative relationship. Mark mounted his own exhibition and produced a book and Charlie really helped him through it. It’s a really lovely relationship that we haven’t set up at all, and we’re seeing more of that happening. So it’s not a one-off – these are ongoing relationships, and often for people with disabilities, that’s one of the hardest things to do. And it’s not just a relationship, it’s an art-making relationship.

GM What you notice here is a sense of welcome. A sense that anyone is invited to collaborate or explore the collection and to really be part of the studio and the organisation. Is that something that APA has always cultivated, or is it something that you’ve done more in recent times?

SR I think in the earlier days, there was more an element of protection for the artists. But certainly, when I arrived here, I was charged with the responsibility to open up the organisation in this way, and my staff are totally behind it. You know, if we want people to know who we are and interact with us, we have to invite them in. There’s probably not a day that goes by when we don’t give somebody a tour, into the backroom spaces of the rooms and the studio. And that might just spring from a chat we had in the gallery, or people might book in.

From an arts manager point of view, everyone that walks in through that door is a potential art buyer or donor, so it’s in our interests to be welcoming. I found that initially when we started doing this, there was a little bit of push back from people who were concerned that the studio should be maintained as a private work space and a sense that the artists shouldn’t be visited. But in fact, our artists adore visitors. I’ve just left a photographer [Tom Ross, for this story] to be chaperoned by everyone upstairs while he took photos. Once again, it’s about giving people a means to have social interaction beyond their normal experiences. And just because people have disabilities doesn’t mean that they should only be working with people with disabilities.

GM It seems that APA doesn’t ‘teach’ so much as incubate individual interests, talents and visions. Can you tell us more about this approach?

SR A visitor from a disability organisation in Italy once asked, ”What do you do if you don’t teach them?”. After 30 minutes in the studio, he understood. The idea is to enable people to develop their own personal artistic style – and this can only be done where artists are permitted to follow their own chosen path – in mediums, context, subject and themes. Staff artists are there to assist, which could mean advising on a technique or colour choice, through to mixing paints. But the golden rule is that only the artist can make their work, unless they are involved in a collaboration. It sounds simple – but for a long time people with intellectual disabilities were denied this freedom of choice in just about everything – so it’s been a strong part of our philosophy since we started 41 years ago.

GM I’m curious Sue, from a personal perspective, what inspired you get to involved in Arts Project Australia?

SR Well, I didn’t know anything about visual art! And I didn’t know anything about disability! So I didn’t really come highly qualified. That said – everyone who works here, bar the business manager and me, is a visual artist, so that’s kind of covered. And there isn’t actually anyone here that is professionally ‘disability trained’. I think that’s part of the allure because the organisation doesn’t operate within a conventional welfare or service-delivery model. We have to comply with every disability standard in the book, of course, but in fact we were complying years before any of the other services, because of our ‘make your own choices’ philosophy.

The strength of the organisation is this really fabulous studio program with a strong group of artists with longevity and a body of work. But there was a lot of more strategic marketing, and advocacy that was yet to be done. And of course fundraising! Luckily I was in the right place at the right time – and luckily the Board recognized that they needed more of an overall manager. There are plenty of artists in this organisation – they don’t need another one!

GM Some of your studio artists, including Alan Constable and Rebecca Scibilia, for example, have found ‘mainstream’ success. What has the impact of this success been for these artists? How do you balance the popularity of some artists with your ongoing work with the group as a whole?

SR You know – every artist approaches ‘success’ in a different way. Some artists have limited verbal skills, but they still show us in a myriad of ways that they understand their success and that they are proud to see their work exhibited and sold. For a number of artists, there is little enjoyment in attending a crowded exhibition, although their families are there to celebrate. But equally, there are many artists who do enjoy social situations and who love the commemorative occasion of an exhibition opening – whether that’s in our gallery in Northcote, at the Melbourne Art Fair, or in a commercial gallery interstate or overseas. Interestingly, the money side of things seems to be of the least interest to most artists – possibly because many have their money managed by someone else – their family or a trustee company.

As a group, all the artists are very generous with the successes of others. They come with a view to making art and developing their art practice in a supportive environment – so success is like the icing on the cake.

GM Where would you like to see Arts Project Australia in terms of audience, artists you work with, visibility and so on, in ten years time?

SR You know what we’d like to see, and we’re actually planning on, is to have more visitors to our Northcote space. We’re not a great walk-past destination. We’re not in the main drag of galleries, but we’re in a really cool location in High Street, Northcote. We don’t see enough of our immediate neighbours – I mean we have people who drive all over Melbourne to come to our openings, but we don’t see enough local people.

The other thing, down the track, is expanding what we do. We’re constantly asked about scaling up, but so far we’ve pushed back and said no, because we don’t want to jeopardise the stability of this organisation before we know what the next funding cycle will be like for us. 60-70 percent of our funding comes through state and federal disability funding, and we make up the rest with fundraising, commissions, philanthropic and arts grants. We’re just embarking on a long term international strategy that hopes to broaden the audience for our artists’ work, as well as strengthening our position as one of the world’s leading supported studios. We want to share our studio and gallery philosophy more broadly, and we want to develop a peer support program in the studio to develop leadership potential in certain artists.

GM And now, a few years in – what do you think makes Arts Project Australia a special organisation?

SR I think it’s the strong adherence to our mission – it’s never faltered. Everyone’s on the same page, so there’s a really strong culture through all the staff in terms of why we do what we do, and that is imbued in all our volunteers, in our student placements, in our interns, and in the people that work with us. When we interview people for jobs, which don’t come up very often now, we take them up to the studio at the end of the interview, and that’s the deal-sealer. We know immediately if people can work here or not – and in fact that’s how we picked our financial auditors last year!

SR Coming back to the studio is so rewarding. I mean I’d been in all kinds of corporate management jobs, arts related and philanthropy related for some time, and the studio is really like the coal face – it’s the reason you’re there. Even though it can be stressful and things can go wrong, you’re in the place where things are being created, and it just makes all the difference. Whatever kind of day I’m having, to go up to the studio and see something being created lovingly, just because someone wants to do it, is really glorious. I guess the thing that I hear more than anything, and particularly from the external artists that come in and work – is that they wish they could remember how to work with such truth, generosity and joy.

A huge thank you to Sue Roff, the artists and all the team at Arts Project Australia. For more information about the organisation’s exhibitions, collaborations and studio, or to get involved, visit: artsproject.org.au.