Inside the Public Loop with David Gianotten of OMA

David Gianotten is a partner in the Rem Koolhaas – founded global architecture and urbanism practice OMA, leading their large portfolio in the Asia-Pacific region. Quino Holland (co-Director of Assemble and its associated architecture company Fieldwork) caught up with David to discuss the role of architects in not only designing buildings but also the space between them.

Quino Holland

One of the themes we are exploring [in the second print issue of Assemble Papers] is the space between buildings. While architects obviously tend to focus on designing buildings, can you talk about the role you see architects playing in designing spaces between buildings?

David Gianotten

When we look at buildings as isolated objects we can easily focus simply on beauty or the needs of users without paying much attention to the effect of buildings on its direct context or the city. An important role of architects is to relate buildings to the urban context and anticipate what the injection of a building can provide the city. In terms of spaces between buildings, I think it would be useful to look at spaces between buildings not as residue or left-over spaces, but rather as public areas that can be consciously generated through the positioning of the buildings for new happenings or rejuvenation of an area. The injection of a new building can often create in-between spaces that are used not only by the designated users of the building but also by visitors and passers-by alike.

QHOMA is an exciting practice because you don’t just design buildings, you engage with much broader cultural, ecological and social issues. A theme that runs through your work is the idea that architecture should contribute to public life. Can you talk about some of the ways that you do this?

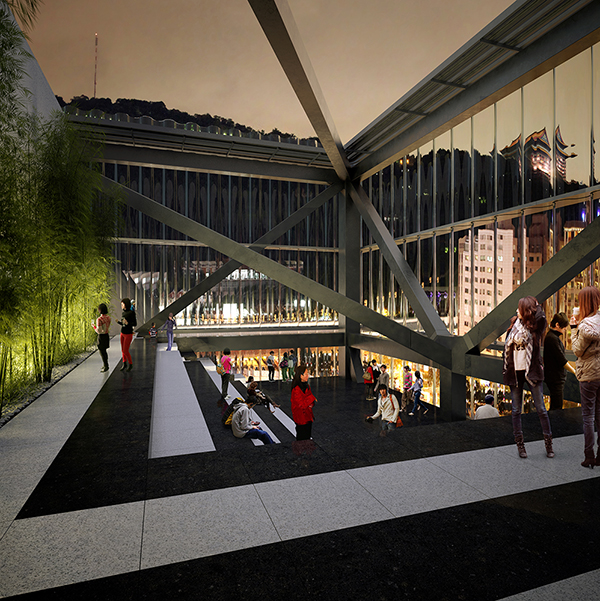

DGIn our projects we often try to blur the boundary between the private and the public. On the one hand, we create public spaces both around and within our buildings through different design gestures that respond to the context. The injection of a Public Loop, on the other hand, is one of the key elements in some of our projects that brings the general public into and through the buildings. For example, in the Shenzhen Stock Exchange project, we have created a public plaza in the CBD of Shenzhen by raising the podium, which could otherwise make the building defensive, to 36m above the ground. In the Shenzhen Stock Exchange there is also a podium roof garden accessible to the general public. For the Taipei Performing Arts Center, the theatre is lifted up so that a plaza beneath it can be created for the possible future injection of the night market.

QHA lot of your buildings draw the city in like this, allowing the public to experience what would otherwise be closed boxes. Even your recent show at the Barbican had a public route through the galleries, which you can pass through free of charge and see some of the exhibits. Why is bringing the city into these spaces important? The Taipei Performing Arts Centre is particularly exciting because it takes the idea of drawing in the city to a whole new level. Can you talk about the public experience you are trying to create within the building?

DGIn each of our projects we try to understand to urban context and respond to it. In the case of TPAC, it was our intent to merge the local grassroots culture of the Shilin night market with the more high-brow performing arts events that would take place in the new theatre. When we first visited the site, we were impressed by the energy of the Shilin night market and decided it should not be eliminated. We have thus designed a performing arts space in which all three theatres are plugged into a central cube to minimise the footprint, so that the whole building can be lifted up to create an open ground plane for future move-in of the night market. The coexistence of TPAC and the night market would enable a mix of high culture and local culture, which we believe can further stimulate creativity of the city.

TPAC is thus a theatre not only for performing arts practitioners or frequent theatre visitors, but also the general public. To further familiarise the public with performing arts, TPAC has a Public Loop incorporated within. People without a ticket can go into the building to look at everything involved in theatre-making – visitors can not only look at the performances taking place in the theatre, but also the back of house facilities and the behind the scenes happenings. The theatre is thus a space not just for cultural consumption. It also puts emphasis on the whole process of cultural production that involves a lot of work.

The three theatres compressed into a single entity also allow the sharing of back of house facilities and more possibilities for theatre spaces. For example, the Grand Theatre and the Multiform Theatre can be combined to form the Super Theatre that provides a 100m theatrical space for experimental works.

QHThe CCTV building is almost a mini city within a building. How do you approach designing for a diverse program and on such a large scale?

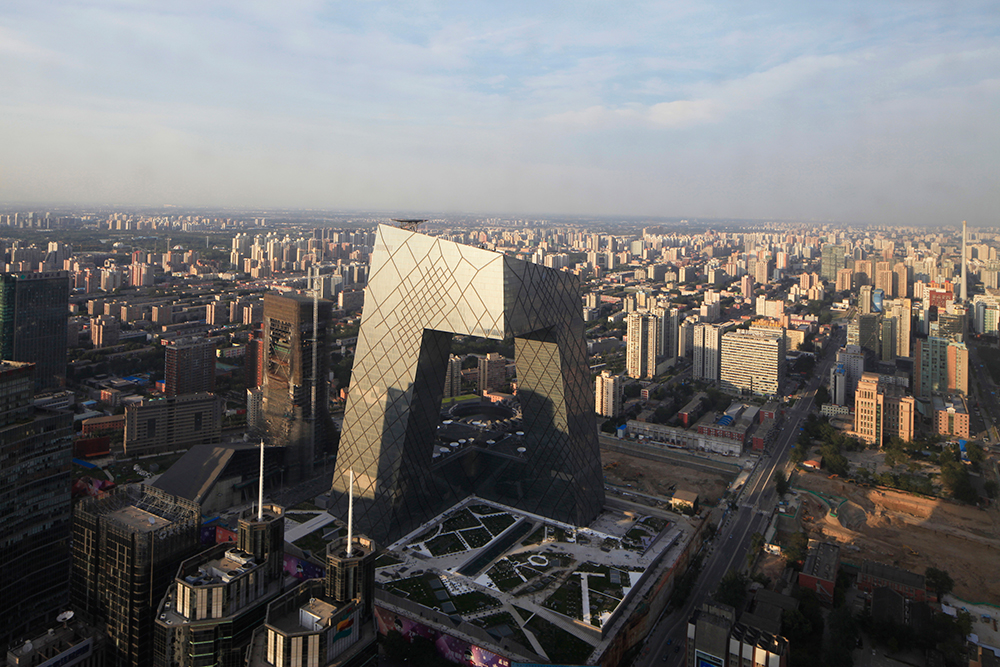

DGThe CCTV Headquarters is a project of a very large scale. While the building responds to the neighbourhood around, the planning of a building indeed resembles urban planning efforts because of the size of the building and the complexity of the program. Having a thorough understanding of the TV production process was important in the planning of this building. The loop form of CCTV encapsulates the entire process of TV-making, which involves generating ideas, pre-production, post-production, broadcasting, etc. It facilitates the communication between the different departments.

In terms of response to the urban context, the CCTV Headquarters, as a loop, does not compete with skyscrapers in the neighbourhood in terms of height. The building appears differently from different perspectives, and it can come across as big or small, strong or soft. Nonetheless it is an important building in the skyline of Beijing and has now become one of the symbols of modern China.

QHWith CCTV, was the public loop intended as a subtle way to encourage transparency and debate?

DGThe CCTV Headquarters has a public loop from which the process behind TV-making is shown. The public can get to understand how TV programs are conceived, produced, and broadcast. While in the past, the process of TV-making is not accessible to the public, this kind of public engagement that the CCTV Headquarters enables will inform the public about how news is actually brought to them. It addresses the ambition of CCTV to further open up to the world and develop into a media organisation on par with its international counterparts. While the West has the tendency to perceive media organisations in China as institutions without autonomy, the CCTV Headquarters addresses the innovation, creativity, and ambition of China’s media. It captures a unique moment in modern China as the country opens up. Although the public loop was not stated as part of the brief, the suggestion to include one was very much appreciated by the Chinese government.

QHIn the Shenzhen Stock Exchange you speak about how the raised podium liberates the ground level and creates a generous public space. How has this space been used since the building opened? Has it worked the way you had hoped?

DGThe general public has been using the public plaza and the popularity of the space has been beyond our expectation. The public plaza created by the Shenzhen Stock Exchange takes a central location in the CBD of Shenzhen, so people in the surroundings have been using the space as a convenient space for sitting out. The public uses the plaza created by the podium and the staircase at the ceremonial entrance alike – they simply sit there, they have lunch there, or when it rains, they take shelter there. The commercial elements at the plinth, as well as the podium roof garden, are often visited by the public.

The building has also created a discourse about the public meaning of skyscrapers. We were invited to participate in a public forum in Shenzhen, and together with the leaders of the Shenzhen Stock Exchange, we evaluated the meaning of the building both to the stock exchange and also to the general public. The leaders of the Shenzhen Stock Exchange have high opinions about the building, and we are also happy with how the building has been functioning.

You mentioned people sitting eating lunch on the ceremonial steps of the stock exchange. When designing these very large and iconic projects how do you deal with the streetscape interface – the human scale of the city?

People have the tendency to get lost in the idea that projects of a large scale will not be able to address the human scale. If we look from a different perspective, a project of a large scale actually allows more possibilities for the interplay between the built volumes and human scale. In a large-scale project, we often have the leeway to decide how the boundary between public and private, or the boundary between the human scale and the urban scale, can be blurred. In our projects, we research on the context; we try to understand the needs of the users and potential users. We often have only one or two bold gestures that address the large urban context of each project, while the whole building addresses the human scale and facilitates the interaction between the building and the users and visitors. We make interventions on the boundary of between volume and human to create more interaction between people and the building.

QHCan you talk about your Taiyuan Industrial Heritage Transformation project and some of the challenges that you’re encountering in attempting to transform spaces never intended for public use into urban spaces?

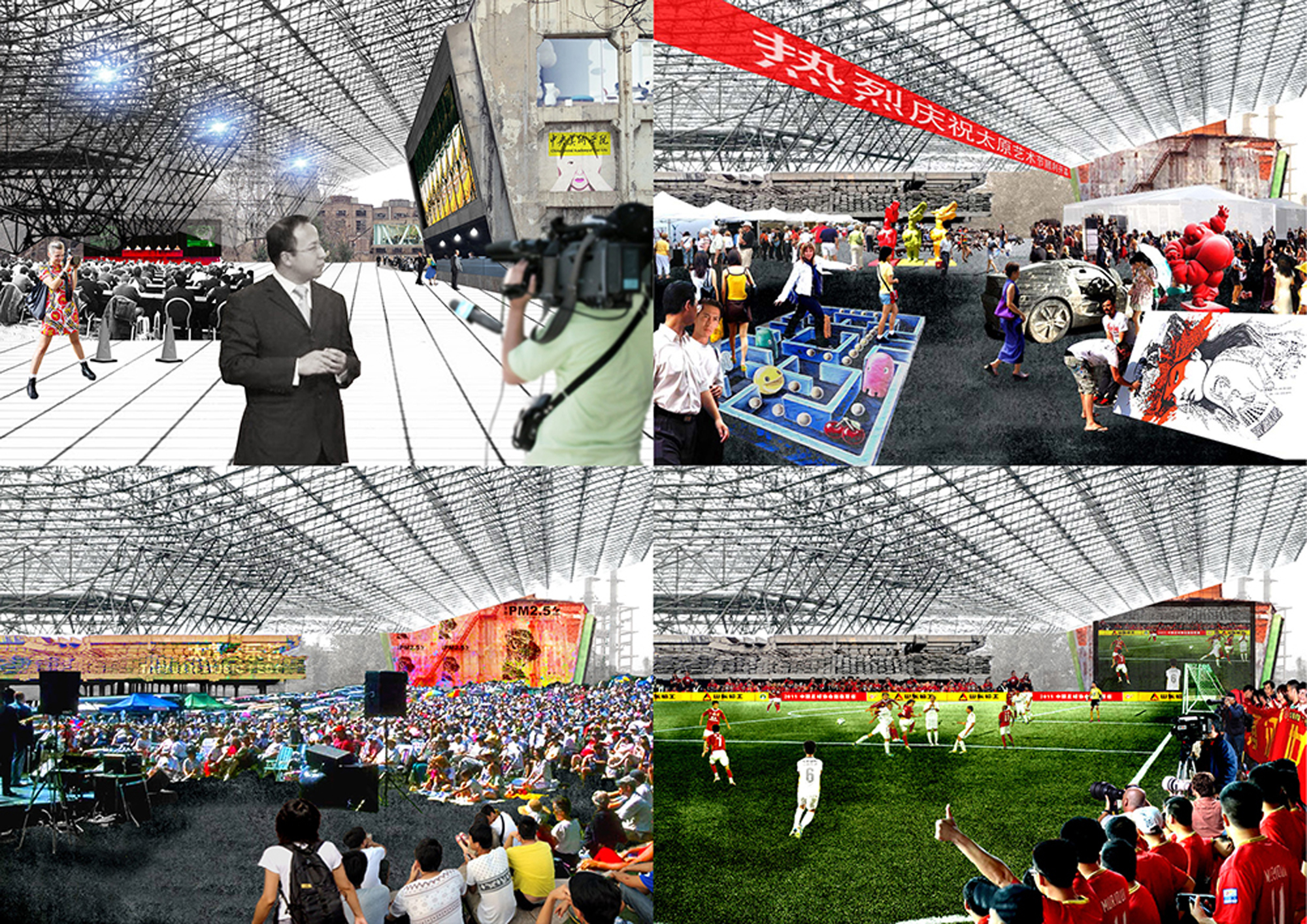

DGTIHT is very interesting – it’s a dream project for an architect. It involves the creation of new urban spaces in an abandoned industrial site of over two million square metres in the northern part of China right in the heart of the city. The government has the clear vision and ambition to revitalise the vast industrial site and create a vibrant area in the city, but at the same time they do not have a clear idea about how to achieve it given the scale of the site and the abundance of remnants. This makes the project at the same time interesting and challenging.

When we first started the project, we did an extensive research on Taiyuan, trying to understand the history of the place, as well as the operation of the industrial complex. In the design process, we have to decide what elements should be kept, and we also have to think about the program elements and funding model to ensure that the site will be vibrant 24/7 and can sustain in the long term. The idea of the masterplan is to first develop buildings of smaller scales, which will spark the development of the whole masterplan. Given the huge scale of the masterplan, it will take 10 to 15 years before it is completed. It is important to initiate momentum at the beginning, while at the same time allow flexibility to ensure the feasibility of the masterplan in the long term.

At this stage we have completed the detailed masterplan, with the construction to begin on site in a few weeks. The buildings, together with the public realm, will generate a system that will address the history and the ambition of the city, as well as the programmatic needs of the users and visitors. The site will become an important cultural and creative hub in Taiyuan.

QHYou and your team lived on the site for ten days to better understand it. Can you talk about some of the things you learnt by doing this?

DGThis project involves using the existing infrastructure not deliberately designed for the newly proposed programs and thus gives a lot of opportunities for surprise. To understand the site and its potential, our team did extensive field research. We lived on site for over ten days and spent a lot of time with the artists who will be the future users of the masterplan. These artists have created works inspired by the site, and they told us a lot of stories about being there. We surveyed the main roads and also documented the industrial remnants. We also looked at smaller elements, such as the machinery, and discovered a lot of in-between spaces that would allow us to inject unexpected functions and generate vibrancy. These unexpected activities challenge the industrial use of the site and bring in more informal uses, which could lead to revitalisation.

Getting to the site and living there is very important for architects when they want to understand a particular context. I was involved in a revitalisation project in Roombeek, the Netherlands, before I joined OMA. In 2000 there was a fireworks disaster in the area which required a large-scale redevelopment. I worked in the disaster site to try to find out opportunities for revitalisation of the area.

QHYou describe this project as aiming to have all aspects of a city. How much of this can be planned and how much can be left up to chance?

DGThere is a diversity of program in the masterplan, which will be developed in phases. ‘Sparks’ will initiate the development of the masterplan. 60% of the site is programmed, while the remaining 40% is flexible and will develop in response to the activities generated by the sparks. The whole masterplan is not planned as a rigid framework, but rather with open ends that allows for changes.

The sparks that we are planting into the masterplan include an appendix of CAFA (Central Academy of Fine Arts), which will have cultural and education programs, such as history and cultural management. These programs are not fully defined yet, but the school will provide the basic facilities needed for the students and the staff. On the masterplan there will also be a museum that showcases the industrial heritage of Taiyuan and China. In addition, artists are invited to produce artworks that respond to the site. These activities, mainly driven by people instead of infrastructure, will serve as a catalyst that would further stimulate the development of both the masterplan and its future program.

QHFrom a personal point of view can you talk to us about the way you use public space in your day-to-day life?

DGA public space is not necessarily a space deliberately designed for public activities. It can be a space that people go to without any particular intention, and happenings naturally take place in the space. If we see public space in such terms, Hong Kong, which is where I live at the moment, actually has an abundance of public space. I like to simply wander around the city and discover informal public spaces that are used by people in unexpected ways. The city is known for its density, but it actually has a lot of green or natural spaces such as country parks and beaches. Given the day-to-day intensity of the city, it is gratifying to discover and use these public spaces designed by nature, to simply get close to it and get dirty with my children.

QHCan you talk a bit about the role you see nature playing in urban spaces?

DGIn the recent Hong Kong and Shenzhen Biennale, we showed ideas related to the Urban Edge and explored the meaning of nature in the urban context. In a place with a high density like Hong Kong, we tend to only focus on the dense urban environment without paying attention to the landscape that enables the city’s hyper-urban condition to thrive. The relationship between urban life and nature is in fact far from antagonistic. Proximity to nature enables densities otherwise impossible, while densities also induce guerrilla gardening and agriculture embedded in any imaginable location. There is a blurring boundary between urban life and nature, and this morphing boundary leads to new possibilities in urban design and resists the prevailing global forces of urbanisation that drive many cities into ubiquitous forms.

QHWhat are the kinds of urban spaces you like and what are the characteristics that make them special? How important is it for you that the city be designed for ‘observant strolling’?

DGA good urban space is one that allows interaction between people and the buildings. It is often not a space designed or organised for specific function or uses. It is a space where people can occupy and where any kind of happenings can take place. It may sound paradoxical, but I think good urban spaces are those deliberately designed for improvisation. These places can be occupied by anyone, and allow unexpected happenings and imagination. Good urban spaces are on the boundary between public and private, deliberate intent and improvisation, trial and error.

QHWorking in Europe and Asia, can you talk about the differences are in the way that new urban space is space is conceived? Are there clear cultural differences in the way that public space is perceived?

DGI would not draw a deliberate distinction between public spaces in Asia and in the West, but public spaces in newly developed cities and ancients are very different. In newly developed cities, which you often found in China, public spaces are often deliberately “designed” and over dimensioned. In cities with history, however, public spaces tend to be embedded within the city fabric. I would appreciate orchestrated improvisation.

QHYou mentioned that you’d like to do some work in Australia but for the onerous procurement process here. A large urban project in Australia or Europe that would take 20 years would be completed in half the time in Asia. Having worked in both contexts can you talk about the benefits of these quicker turnovers and how the west can learn from this?

DGIn Asia, decisions for development come quickly because encompassed in all the decisions is often also the flexibility for change. As in the case of TIHT, flexibility has already been envisioned in the beginning of the masterplan’s development. In contrast, in Australia or in Europe, it takes a much longer time to make decisions as the masterplans are much more rigid and ideas have to be largely in place from the onset. It is good to plan everything thoroughly from the beginning but rigid planning also eliminates possibilities. Flexibility, in contrast, allows unexpected happenings that are sometimes essential for the creation of vibrancy. It also increases adaptability to any unforeseeable risks.

QHWhich city or site do you think is ripe for an OMA intervention?

DGThere are a lot of places in which we would like to work. Australia is definitely one of those. I am also interested in the countryside of China at the moment; it would be interesting to work on a project that looks into the space left behind in the course of urbanisation.

A big thank you to David Gianotten and OMA. Photography by Iwan Baan and Philippe Ruault, courtesy of OMA.