Movement of the crowd

Photographer Rafaela Pandolfini naturally looks to the movement of the crowd in places where people are preoccupied with carrying out contemporary rituals. Art openings, parties, clubs, the beach and the park. Her interest is in the way people move together or alone, their shapes and patterns against vast or modest backgrounds. Their objects, their dress, and what they use and discard.

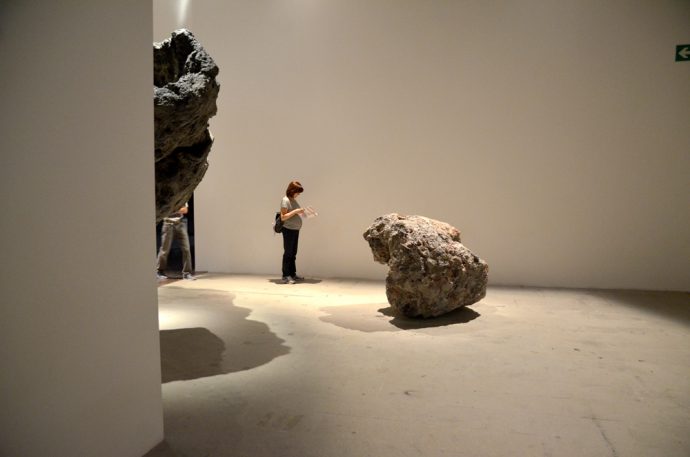

Photographer Rafaela Pandolfini (a regular AP contributor) naturally looks to the movement of the crowd in places where people are preoccupied with carrying out contemporary rituals. Art openings, parties, clubs, the beach and the park. Her interest is in the way people move together or alone, their shapes and patterns against vast or modest backgrounds. Their objects, their dress, and what they use and discard. In July 2013, Rafaela and her young family made the pilgrimage to Venice to experience the oldest event on the international contemporary visual art calendar, the 55th Venice Biennale. Here she shares her images and ideas from Venice: focusing on the Biennale through its audience and photographing the movement of the crowd.

“What I love is the moment when the viewer is so engrossed by what they are seeing and experiencing that they become physically immersed, bodies leaning in or away, perhaps fidgeting or standing completely still. Lost in an idea or image, oblivious to anyone else around. This is often fleeting in a busy exhibition space – someone usually brushes past, interrupting their connection with the work. Witnessing these (most likely) unintentional emotional reactions gave me an insight into the meaning and reading of certain works. For example, in the Central Pavilion, photographer Kohei Yoshiyuki’s perverse cycle The Park (1973) seemed complete as I watched a striking viewer peering back at the voyeuristic images. The domino ‘peering affect’ was there again with Ellen Altfest’s detailed paintings that demanded close viewing. Maria Lassnig’s bright paintings “…depict her body as she experiences it rather than as it appears” (taken from Lassnig’s room sheet) and this seemed to resonate with the captivated audience.

In a beautiful open space at the end of the Arsenale, Bruce Nauman’s video installation Raw Material with continuous shift – MMMM (1991) was showing. It called out for the audience to move with it, but of course, only our two-year-old daughter Rozsa took up the challenge. She spun around and around, imitating Nauman’s head, giggling uncontrollably. People stopped and laughed – a warmth and connection amongst passers by. The Encyclopaedic Palace exhibition was gargantuan. Coming back to Australia, trawling through my documentation and reading about the Biennale, I wondered about the amount of work shown and the desperate need we all felt to “get through it” in such a limited amount of time. Meticulously and ambitiously curated by Massimiliano Gioni, his curatorial motivation seemed to reflect our “desire to see and know everything, and the point at which this becomes an obsession.” (Massimiliano Gioni, taken from the exhibition catalogue)

In an article entitled How to survive the Biennale, the Spectator’s Owen Humphries used the term “art flaneurs with iPhones” to describe the Venice audience. This, I felt, was an oxymoron, as our incessant need to capture and view the art through our iPhones actually took away from the possibility of reverie. Obsession with “seeing it all” became image overload – which became the point. “The exhibition examines the roles of images and the functions of the imagination…and in doing so questions what is left for our dreams, visions and hallucinations in an era besieged by external images.” (Massimiliano Gioni, taken from the catalogue). A very lively pavilion was Great Britain’s in which artist Jeremy Deller and curator Emma Gifford-Mead provided everything art tourists could possibly need: a brass band, free tea, greenery, an outdoor area and David Bowie tour photos. It was colourful, spacious, light and bright. Yet the work was sobering. Deller’s use of pop culture felt intentional and was successful in captivating a lively audience – but I wondered whether this meant his message didn’t linger? At the Australian pavilion, artist Simryn Gill and curator Catherine de Zegher had created a subtle and soft space to show the impacts of mining on the beautiful landscape of Australia. As we passed through, people hung around, looking at the delicate works and taking their time to piece together what was on show.

I found Theirry De Durve’s paper on biennales interesting, as he calls on us to use our ability to discuss the feelings we have in reaction to a work as the basis of the argument that what we have experienced is art. I welcome this idea. I looked for these feelings expressed intentionally or unintentionally as I scrutinised the exhibition and reactions of the crowd through a camera lens. The final work we saw was the Polish Pavilion with Konrad Smoleński’s installation, Everything was forever until it was no more. When I went to see the work, nothing was happening. In the room sat two very large bells – as the space filled with viewers, the tension grew. We all waited nervously with ears plugged for the clock to hit a quarter past the hour so that we could stand a metre away from two giant bells tolling. As they began to toll, Rozsa made a beeline for the tadpoles in the mossy pond outside and we knew it was time to depart. Feeling uplifted and exhausted, we limped towards our ‘aperativo’ at the close of our second and final day at Venice”.

To view more of Rafaela’s works, visit rafaelapandolfini.com.