London’s Sound Diplomacy on urban planning for music

At the recent Melbourne Music Cities Convention, ARUP’s Bree Trevena pointed out that music is everywhere – it’s in our cars, homes, workplaces and in our headphones. It crosses spatial boundaries within a city. From the time we are soothed by lullabies as children, we are tapping into a language that connects us to other people and to ourselves in a way that is very real, but nearly impossible to explain. Music affects us in ways that are as mysterious as they are significant. A growing body of research now shows that music can be used to improve cognitive function in stroke and dementia patients, improve symptoms of depression, and help people manage post traumatic stress disorder.

“The social value of music is huge, because it can communicate to us in ways that don’t require language,” says Shain Shapiro, organiser of the Music Cities Convention and CEO of Sound Diplomacy. “It’s a great equaliser – if you’re at a concert enjoying what’s happening in front of you, just like the person next to you is, then you’re equal in that experience. When policy-makers are trying to close divides between people, music is just one tool, but it’s also one of the most powerful and transferable tools that they can use.”

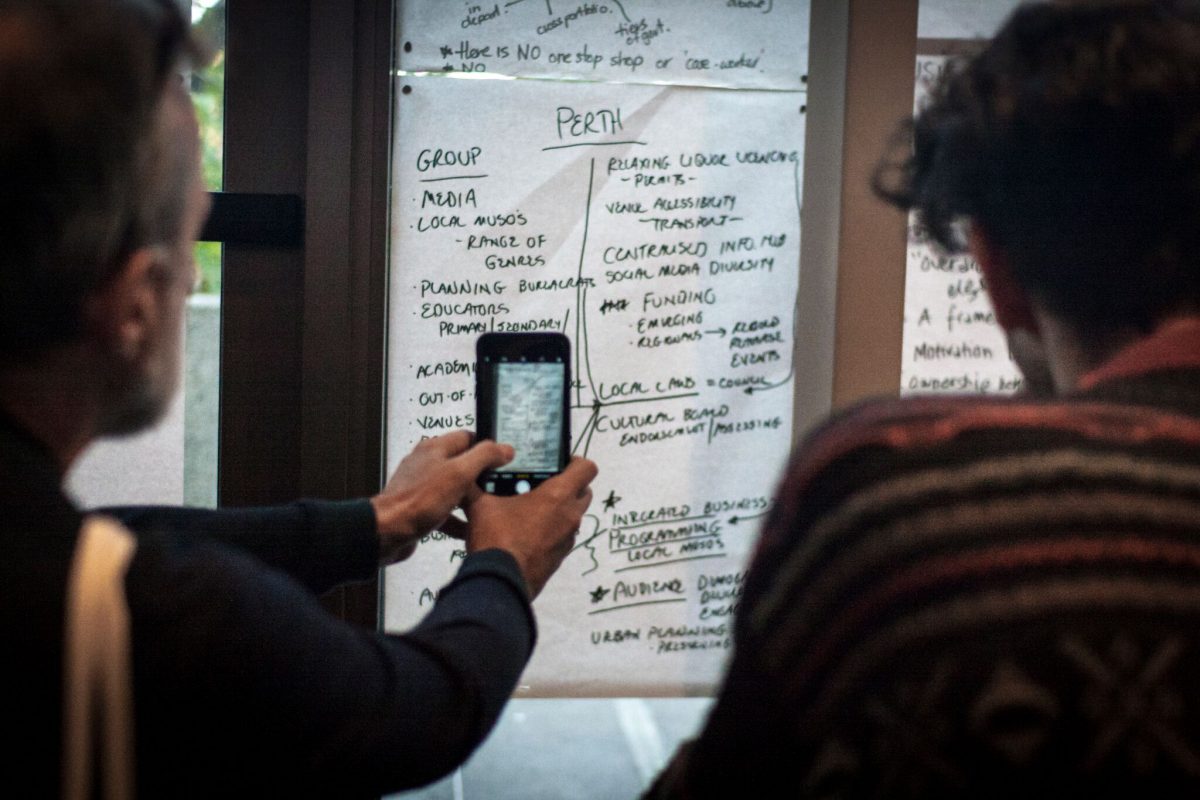

Shain Shapiro is a self-described music urbanist, a term that he admits is hard to define. But at its core, he believes that music has the potential to make our lives better and should therefore be part of any urban strategy. In 2013, Shapiro founded Sound Diplomacy in London with the aim of bringing music communities, urban planners and policy-makers together. Once they were in the same room, he wanted to help them communicate their ideas to each other more clearly. “Governments are starting to take an interest in this,” Shapiro says. “Because we’re not just talking about having live music venues on every corner, or having more festivals. We’re talking about how to improve our quality of life – our transport systems, education system. We’re using music as part of the web of systems that make cities work.”

And it would appear that governments are genuinely interested. Sound Diplomacy’s achievements include working with the Mayor of London, advising the government of Cuba on behalf of the United Nations and, more recently, writing Brisbane’s music strategy. As governments rush to make their cities more livable, it makes sense to plan for something that has such inbuilt potential to create shared experiences between people.

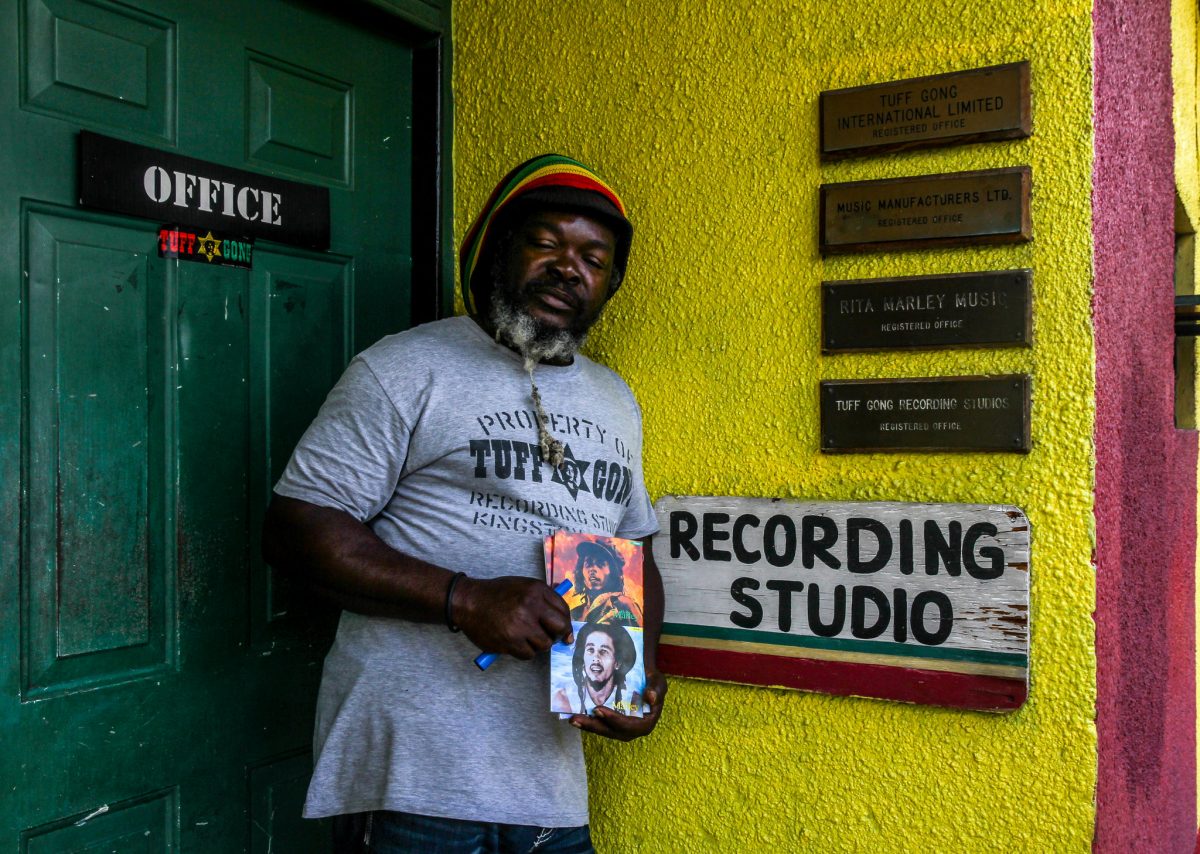

Shapiro is clear about one thing – it takes a multifaceted approach. A recent study showed that Melbourne has more live music venues than any other city in the world, leading to claims that Melbourne was indeed the world’s greatest music city. According to Shapiro, that’s only one way of looking at it. “Melbourne does a lot of things well, but having the highest number of one thing alone doesn’t necessarily make for a great music city,” he said. “Too often the term ‘music city’ is conflated with live contemporary music venues and that’s not accurate. It’s more than that. It’s education, recording facilities, equipment hire venues for classical music, jazz and traditional music forms from migrant communities. It’s about providing access. There are so many things to consider.”

So where does a government start when looking to create a music-friendly city, or a ‘music city’? Shapiro says that the first thing that needs to change is how we calculate land values in urban areas. One of the biggest problems for music and its related industries is that venues, concert halls, recording and rehearsal spaces are often located in areas where land value is very high. As populations in cities boom, housing is often the top priority for governments. “It comes down to the fundamental question of how our cities are being developed,” he said. “What’s the relationship between the value of the land, versus the value of what’s happening inside the building?”

Competing interests in dense spaces present a problem. According to Shapiro, housing is often the most pressing concern for a government. As cities try to keep up with housing demand, apartments will take precedence over spaces of cultural production. “Real estate investments are calculated [according to] a simple calculation,” Shapiro said. “The value of the land often trumps what happens inside the building. This means that cultural uses, from libraries to swimming pools to music venues, are seen as secondary to housing, rather than in line with housing. We simply need to have a wider definition of land use.”

Many of these ideas are not new; in fact, a lot of what Shapiro is saying mirrors the ideas shared by architects and urban planners like Jan Gehl – that urban planning needs to consider people first. It is not enough to build a city focused entirely on development; we need to take a holistic approach to urban planning if people are going to enjoy a quality of life, and in turn make our cities ‘livable.’ Shapiro reinforces that building houses and apartments without giving any thought to recreational spaces is not sustainable. He acknowledges that music industries and communities have not yet found the best ways to communicate the inherent value of what they do, but that the approach needs to be systematic. “Governments understand the language of economics,” he says. “Music is more than economics, but doing research and mapping the economic benefits of music in a city is a good way of getting into these conversations. All over the world, governments are consulting with industries as they strive to make their cities more livable – we need to take those opportunities.”

It will probably be a while before a major city sees a change in the way land value is calculated. However, there are examples of governments engaging with music as a tool to address social problems. For example, last year in the UK Nordoff Robbins held a parliamentary roundtable looking at how music can be used to improve mental health. In 2016, London established the London Music Board to bring music education, venues, tourism and other areas together to support each other. Colorado has a robust music strategy that focuses on local musicians and education, as does Brisbane.

So what would Shapiro like to see in the future? In essence, a world where music is planned for in urban development, and recognised more widely for its social benefit. “If the expertise isn’t there to respond to government consultation in the desired bureaucratic ways, then the process will be useless,” he says. “In the future, I want to have university courses dedicated to music urbanism, so that we have people around the world who can articulate these things. I’m not advocating for music everywhere – I’m advocating for music to have a voice everywhere.”

Thank you, Shain, for an introduction into the importance of music in cities – a topic we will continue exploring in 2018. You can read more of Shain Shapiro’s thoughts on cities, sounds and the night-time economy on Twitter.