Offset House: framing Australian suburbia

Australia is one of the world’s most urbanised nations – and one of the least dense. Fewer than 10 percent of Australians live in close proximity to a city centre, with most inhabiting the suburban hinterland. Ever since Robin Boyd’s lambasting of ‘featurism’ in his landmark 1960 book ‘The Australian Ugliness’, the ‘burbs have been somewhat of a no-go zone, professionally and culturally, for urbanite Aussie architects. A recent project by design duo otherothers seeks to reframe the much-maligned suburban house as a site for socially and environmentally responsive living. “If the language of the McMansion is merely a veneer, shouldn’t Australian architects see right through it?” So ask Grace Mortlock and David Neustein of otherothers with ‘Offset House’, their un-supersized suburban house project currently on show as part of the inaugural Chicago Architecture Biennial. By stripping away low-grade construction and materials and ‘poor planning and illogical furnishings’, ‘Offset House’ celebrates the humble timber stud as the frame for architecture – and a revised Australian dream. Here, David and Grace reflect on ‘Offset House’ and the response to their downsized McMansion in our era of urbanisation and climate change.

This is a story about models, studs and suburban houses.

On the third of January, following a three-month program of exhibitions and events that has enticed some 300,000 visitors, the Chicago Architecture Biennial will draw to a close. The conclusion of North America’s first architectural biennial will also bring to an end our first participation in an international exhibition. On show at Chicago’s Cultural Center alongside about 100 other exhibitors, Other Architects (in the guise of its speculative offshoot, otherothers) is currently rubbing shoulders with some of contemporary architecture’s biggest names, including Lacaton & Vassal, Junya Ishigami, Sou Fujimoto and Office KGDVS.

A disorientating labyrinth of neoclassical, Art Deco and utilitarian architecture, the Cultural Center was once Chicago’s public library. A few select architects were commissioned to create site-specific installations within this incredible building. Atelier Bow Wow, for example, has built a series of platforms and swings within the inaccessible void at the building’s core, while SO-IL’s Passage creates a gothic canopy over an internal ramp. An equally elite crew: Tatiana Bilbao, MOS Architects, selgascano and Vo Trong Nghia Architects; was invited to build full-sized prototype houses inside the Cultural Center’s walls. By comparison, our Offset House is relatively small, comprising a pair of architectural models: a suburban house reduced to 1:10 scale, and a suburb of eight houses at 1:50 scale. Standing on symmetrical wooden plinths, our models flank the doorway to the Cultural Center’s lofty exhibition hall. In a playful echo of the iconic lions that guard the entrance to the nearby Chicago Art Institute, anyone entering the hall must first pass through Australian suburbia.

Over the past decade, several international architectural expositions have been established in the model of the Venice Architecture Biennale, including events in Oslo, Rotterdam, Shenzen and Hong Kong, Lisbon, Tallinn and Bruges. Initiated by Mayor Rahm Emanuel and intended to re-establish the city as a generator of architectural discourse and innovation, the Chicago Architecture Biennial is the most recent and significant of these new gatherings. Unlike its Venetian forerunner, Chicago’s offering remains free to the public for its duration, with funding coming exclusively from private industry (BP being the controversial major sponsor). And whereas Venice includes official national delegations, each responsible for selecting its own country’s representatives, Chicago features only individuals and teams.

‘The State of the Art of Architecture’ is the inaugural Biennial’s theme. In the words of artistic directors Joseph Grima and Sarah Herda, this loose remit offers “an opportunity to take stock of architectural projects and experiments from around the world, establishing a broad foundation for future editions.” Adopted from Stanley Tigerman’s 1977 Chicago architecture conference of the same name, the purposely open-ended theme has turned out to be something of a self-fulfilling prophesy. If you invite architects from all over the world to simply do as they please, the sum total of their efforts might well describe the current state of architectural culture. Herda and Grima culled participants from a list of 500 architectural firms worldwide. They invited responses from 20 Australian offices, with Other Architects/otherothers the only local practice to make the cut. Seemingly overnight, we had been appointed as the antipodes’ architectural ambassadors, unofficial representatives of ‘the State of the Art of Architecture’ in Australia.

To the outsider, it may seem that Australia’s architecture consists entirely of singular pavilions in picturesque landscapes. By far our best-known architect, Glenn Murcutt has built his Pritzker Prize-winning career largely on such work, while his acolytes – including Peter Stutchbury and Sean Godsell – feature regularly in publications and exhibitions abroad. To wit, a Google image search of ‘Australian architecture’ brings up the following suggested subheadings: ‘Rural’, ‘Famous’, ‘House’, ‘Domestic’, ‘Styles’ and ‘Outback.’ In reality, idyllic dwellings in the wilderness, often used as second homes or holiday rentals, are a luxury beyond the means of most. Australia ranks amongst both the world’s most-urbanised and least-dense nations. Occupying the largest average homes and commanding the most living space of any nationality, the majority of Australians live in mass-produced suburban housing.

Despite this reality, Australia’s architectural elite has repeatedly treated the suburbs with disdain. In his influential 1960 book Australian Ugliness, Robin Boyd conflated the brick-veneer suburban house with the nation’s racist White Australia policy. More recently, Murcutt claimed that suburban houses are “not architecture.” “The man who has made liveable houses an art form decries the McMansions that rely on airconditioning and heating, rather than thoughtful use of design and material,” writes Michael Bleby in his recent article on Murcutt for the Australian Financial Review. “My head is just hitting on a wall when you think about it all,” is Murcutt’s exasperated response.

It seemed inappropriate to us that the champion of Australian architecture could decry suburbia without offering any solutions. It also seemed like the perfect place to begin a discussion about ‘The State of the Art of Architecture’. We set out to make the ‘ugliest’ thing possible – stock standard, face brick suburban houses with applied ornamentation – as beautiful as we could manage. We delighted in the opportunity to challenge the way Australian architecture is represented abroad, subverting its airbrushed and idealised imagery. Of course, we were not the first to venture into the suburbs. Though venerated far more rarely than big budget architecture in spectacular locations, suburbia nonetheless remains a frequent subject of investigation. Offset House draws on a long list of precedents, especially the projects of Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi (who were finally awarded the American Institute of Architects Gold Medal earlier this month based on 50 years of groundbreaking work).

Since the Biennial’s opening in October, our installation has attracted far more media interest than we expected. Sitting alongside other projects that seek to address land scarcity and social inequity, Offset House has taken on its own life, trumpeted as a possible solution to the housing crisis in America and beyond. Had the project been built yet, a Chicago critic wanted to know, and were there any developers on board? An Australian journalist asked us to support the idea with an itemised cost estimate. This focus on Offset House’s technical aspects has surprised us, as we intended our work to raise questions rather than provide answers, to act as a provocation rather than a solution.

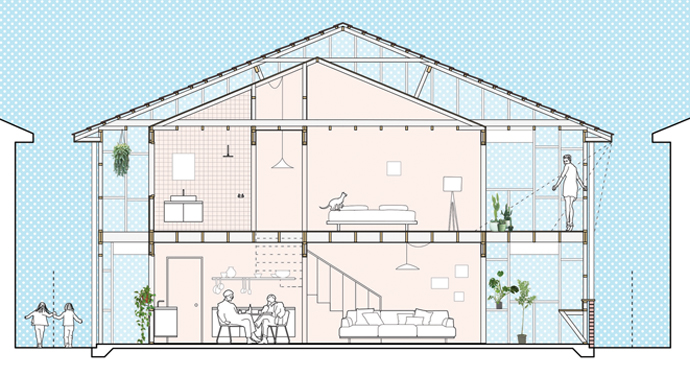

In Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight, a horrific explosion transforms the heroic Harvey Dent into the villainous Two Face. While one half of Dent’s handsome face remains, the other becomes a burnt visage of muscle, tooth and bone. Offset House is Two Face in reverse. One side of our models depict ‘heroically’ altered suburban houses: brick veneer stripped away to reveal intricate timber frames beneath. The exposed frame becomes a permeable line of enclosure, providing light and air to the rooms within, which are reduced in size, or even divided to create separate dwellings. Generous verandas allow for private outdoor living, removing the need for property fences. In contrast to this utopian vision, the other half of the models is seen pre-transformation, a confronting gaze into the suburban liver-coloured brick abyss. While the amount of care taken in modelling existing suburban houses may seem fetishistic or perverse, our true aim was to demonstrate the hidden beauty – the very ‘studliness’ – of the common timber stud. Anyone who has seen a naked stud frame during construction can testify to its intricate beauty. Invented and industrialised in 19th century Chicago, the cheap, lightweight and easily modified stud remains an essential architectural component. By glorifying the stud, Offset House attempts to demonstrate that architectural potential is latent within any suburban house. It’s up to us to see it.

Many thanks to Grace Mortlock and David Neustein for sharing their reflections on Chicago and their droll, inventive yet pragmatic ‘Offset House’. Other Architects is a Sydney-based architectural practice founded by Michael and David Neustein. Current projects vary in scale: from cemetery masterplans to small-scale residential developments, new ‘dwellings and house extensions. A newly formed offshoot of Other Architects, otherothers explores areas beyond the scope of conventional architectural practice. Led by Grace Mortlock, otherothers undertakes research, speculation, exhibitions and events. For more information, visit: otherarchitects.com and otherarchitects.com/otherothers.