Reimagining Kensington’s Younghusband Precinct for future communities

References

In 19th-century Australian cities, some of the areas with the highest land values were inner-city industrial zones. These trailed only prime commercial strips – akin to the dark blue Boardwalk and Park Place in Monopoly – in their value per square metre. This may seem odd today, as many of us have grown up in cities that, since the 1970s, have deindustrialised. In most capital cities, shipping and industry were not just zoned out of the centre but performed in overseas locations, quite literally out of sight and out of mind.

The high value of urban industrial lands came from their proximity to boat- and barge-based conveyance, markets and labourers in a time before dispersing transport technologies. In the Victorian era, smokestacks, and even the black smoke they belched out, were, initially, the pride of industrialising cities; a visible sign of ‘progress’ and coming affluence.1

In the mid-20th century, acid rain, pervasive smog and riverine pollution2 led grassroots activists to sound the alarm on environmental degradation, jump-starting environmental movements around the world. Simultaneously, the globalisation and modernisation of manufacturing shut down many inner-suburban industrial zones. Some of the largest structures in cities – such as turbine halls, smokestacks, shot towers and gasometers – fell silent and took on the air of dinosaur skeletons, towering over their surrounding neighbourhoods.

While Narrm/Melbourne was never as industrial as cities in the north of England, the midwestern United States or Germany’s Ruhr valley, it proceeded along a similar trajectory of factory-building followed by rapid deindustrialisation with the rise of containerised shipping and changes in production. This was particularly true in Melbourne’s west, which, because it feeds into the port, was home to many warehouses and small factories. The opening of the West Gate Bridge in 1978 led much of the industry clustered in Kensington and Footscray, along the Maribyrnong River, to shift to the outer west.

The departure of intense industry has made the area an attractive place to live and work, especially as housing stock and office space in the CBD has grown scarcer.

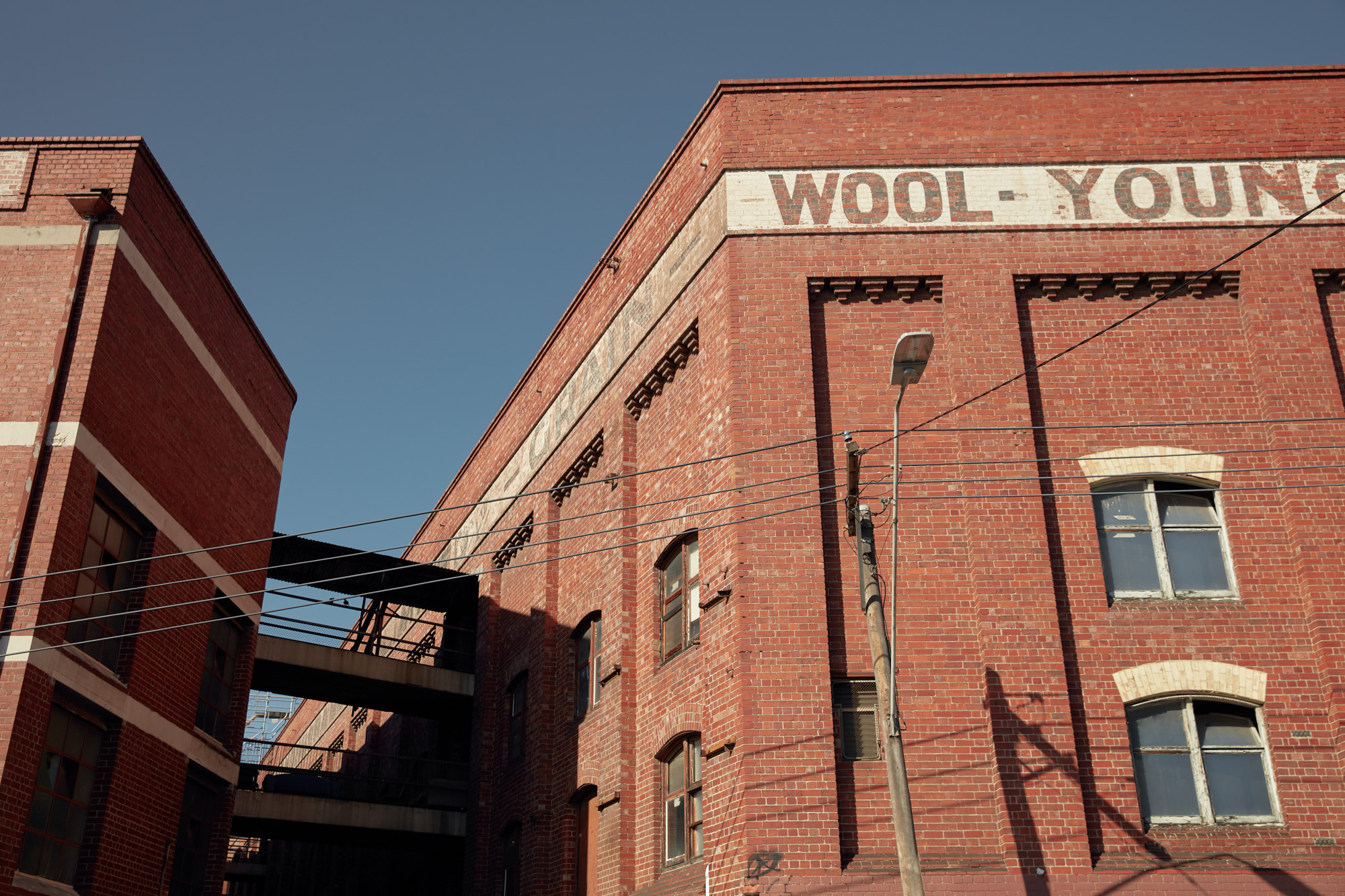

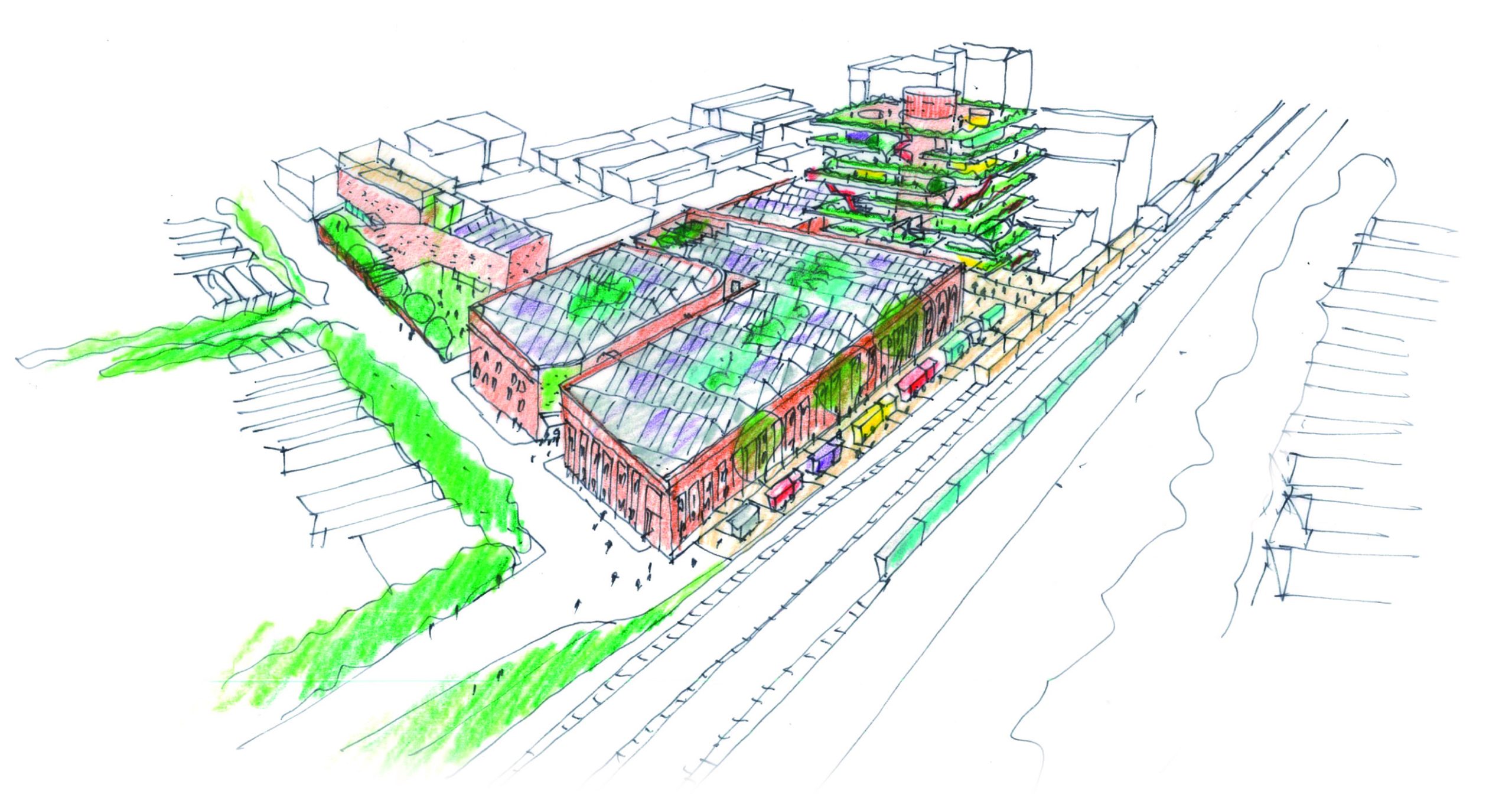

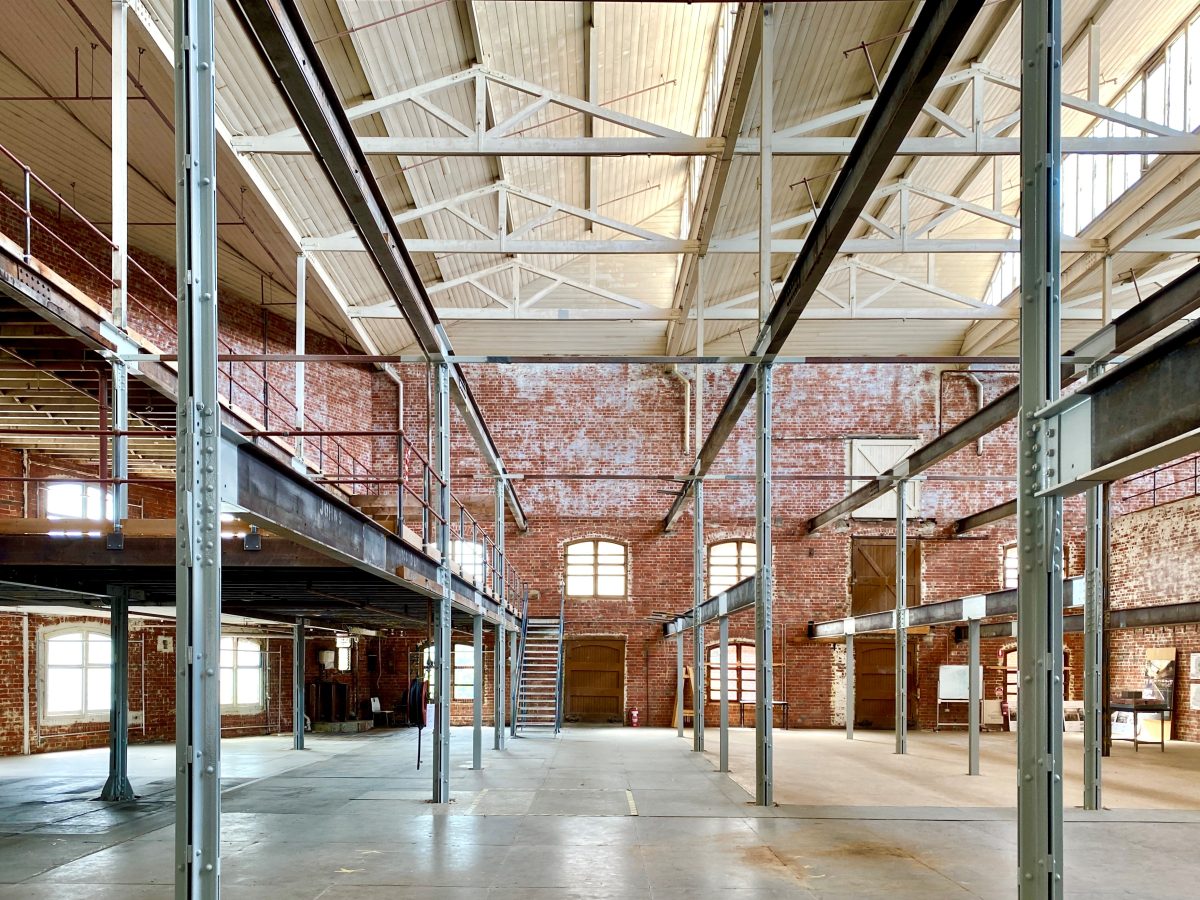

Construction is currently underway by joint-venture partners Ivanhoe Cambridge, Irongate, and Built at what will become the Younghusband precinct, a 1.57 hectare mixed-use site in Kensington that will, in its first stage, provide over 17,000sqm of adaptive reuse workplaces and ground floor retail. Its name comes from the last wool broker to trade there, who operated until 1970. The site is anchored by a 122-year-old redbrick wool store with an interior L-shaped bluestone laneway. Peter Miglis, a principal at Woods Bagot and the project leader, is excited about the reopening of the space to the communities around it. “It’s been off limits for a long time,” he says. “It’s got a beautiful laneway in it, and we wanted to open that up to everyone… to invite in the Kensington residents who have walked by it for so many years but never been able to enter.”

The move to renovate and repair old buildings is often referred to as ‘adaptive reuse’.3 It has been going on for centuries – just think of buildings in the Mediterranean and Middle East where one sees civilisation after civilisation using the same foundations4 to build out structures with an amalgam of styles – but it was presented as a principled alternative to the wrecking-ball-friendly urban renewal of the 1950s to the 1980s. During this period, wealthy cities in Global North countries cleared vast quantities of land through government-backed programs, a process that the New York activist Jane Jacobs compared to as the “pseudoscience of bloodletting”.5 Jacobs helped to thwart a proposed Lower Manhattan Expressway in the early 1960s, but many buildings that would now be viewed as old and quaint were knocked down for new modernist towers or, worse yet, sprawling.

Jacobs helped to thwart a proposed Lower Manhattan Expressway in the early 1960s, but many buildings that would now fields of surface parking. The generation that came of age immediately afterward looked at the voidsfields of surface parking. The generation that came of age immediately afterward looked at the voids left behind with disdain and, in their search for authentic remnants of the urban past landed on industrial areas, many of them emptied out due to new modes of transport, like containerised shipping, and to the migration of manufacturing.

While Narrm/Melbourne lost some of its industrial heritage to urban renewal it has been able to retain many significant structures, thanks in part to a vocal heritage advocacy community.6 However, some of these structures, particularly those incorporated into retail environments, may no longer be legible as part of the city’s industrial past.

The adaptive reuse of industrial sites has, until recently, focused on Footscray, because of its direct rail link to the CBD. In the 2010s, the Deco Olympic Tyre Factory in Footscray was converted into housing; a former garment hub, the Bradmill Factory, in Yarraville, is also slated for a housing conversion; and the historic Kinnears Ropeworks in Footscray’s centre is being developed as a high-density mixed-use precinct. More recently, industrial south-east and east Kensington have come onto the radar as sites for future development, with Younghusband as one of the biggest.

As works started, the Woods Bagot team are excited to share the industrial wonders that they have discovered at the site. “You really get an appreciation for the materials they used [on the wool stores] – they came from Ireland, from England, and from all over. You can see their origin stamped on them, literally tattooed onto the surface of the beams. The riveting detail is amazing, like the Sydney Harbour Bridge, [with] columns are fine as stilettos,” Miglis says.7

The post-industrial sites of New York provided some inspiration for the team who visited former maritime buildings on Brooklyn’s waterfront, like Industry City, a one-time terminal for navy ship making that is now home to creative industries, including makerspaces and hospitality. When asked about the rail lines that Younghusband fronts onto, Miglis says that his team “decided to embrace that infrastructure and make it something that people can look out at and walk up to on the new pathways”, seeing the trains passing by would be a unique draw of the site, and not something to be hidden away.

The patina of age may also dispel some of the preciousness of a new building, allowing the new occupiers to feel more at home. Miglis notes that after Younghusband & Co wool brokers moved out in 1970, there were “a bunch of ad hoc uses” for the site. While the current project is highly intentional, the firm is also interested in preserving flexibility and spontaneity. They hope that, once the building is complete, it will also be home to a diversity of occupants.

Younghusband can be an inspiration to similar projects around Australia, and the world, positing a way forward for cities in which industrial heritage – and the embodied carbon contained in old buildings – is retained. The team developing Younghusband is looking at industrial heritage as more than facades, or the preservation of a few charismatic buildings. They aim to extend adaptive reuse to include structures that were once overlooked. In the future, the hope is that these projects will educate and inform newcomers to the city and the precinct about the labour that once took place there.

- See Janet Greenlees, ‘Unhealthy environments in Victorian Britain: when air quality began to matter’, Modern History Review, 2021.

- This was dramatised when the Cuyahoga River, which flows through Cleveland, Ohio, caught fire on 22 June 1969 because of the industrial runoff that had settled on the water’s surface.

- See Liliane Wong, Adaptive Reuse: Extending the Lives of Buildings, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, 2016.

- For more on the archaeology and creation of public space in this region, see Ömür Harmanşah, Cities and the Shaping of Memory in the Ancient Near East, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2013.

- Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Random House, New York, 1961.

- Dozens of structures built at the height of ‘Marvelous Melbourne’ affluence were torn down. Many of them by Brunswick-based demolition firm Whelan the Wrecker. Significant losses include: the 12-storey Australian Building (1889–1980); the ultra-ornate Federal Coffee Palace (1888–1973); Fink’s Building (1888–1969); and Queen’s Coffee Palace (1888–1970), which was replaced by the Cancer Council Building (now dilapidated).

- For more on what went into riveting large structures in the early 20th century, check out the State Library NSW’s multimedia look at the labour involved in holding the bridge’s steel in place. See ‘The Bridge – Episode three: Six million rivets’, 2018. State Library of New South Wales.