Envisioning the future of local communities through artmaking

In a fast-paced, impersonal world, how can we cultivate a sense of connection with those around us—and what role might art play in this? As part of Melbourne Design Week 2022’s Design Broadcasters commission, nipaluna/Hobart-based artist and writer Jade Irvine spoke with Neal Haslem of Commoners Press on how slower, more manual technologies can open our imaginations to our desires and aspirations for our local communities.

Jade Irvine:

Hello, my name is Jade Irvine and I flew over from lutruwita/Tasmania to attend a workshop for Melbourne Design Week in March 2022. Titled ‘these three words,’ the workshop was run by Commoners Press, a local print studio based on Wurundjeri land and part of Coburg Studios in Coburg North. The collective aims to work on projects that are community-focused, experimental and sustainable in nature, and the members of Commoners Press are a group of artists, designers, and academics all taking on different roles within the cooperative. There’s Neal Haslem, Rob Eals, and Jan Brueggemeier.

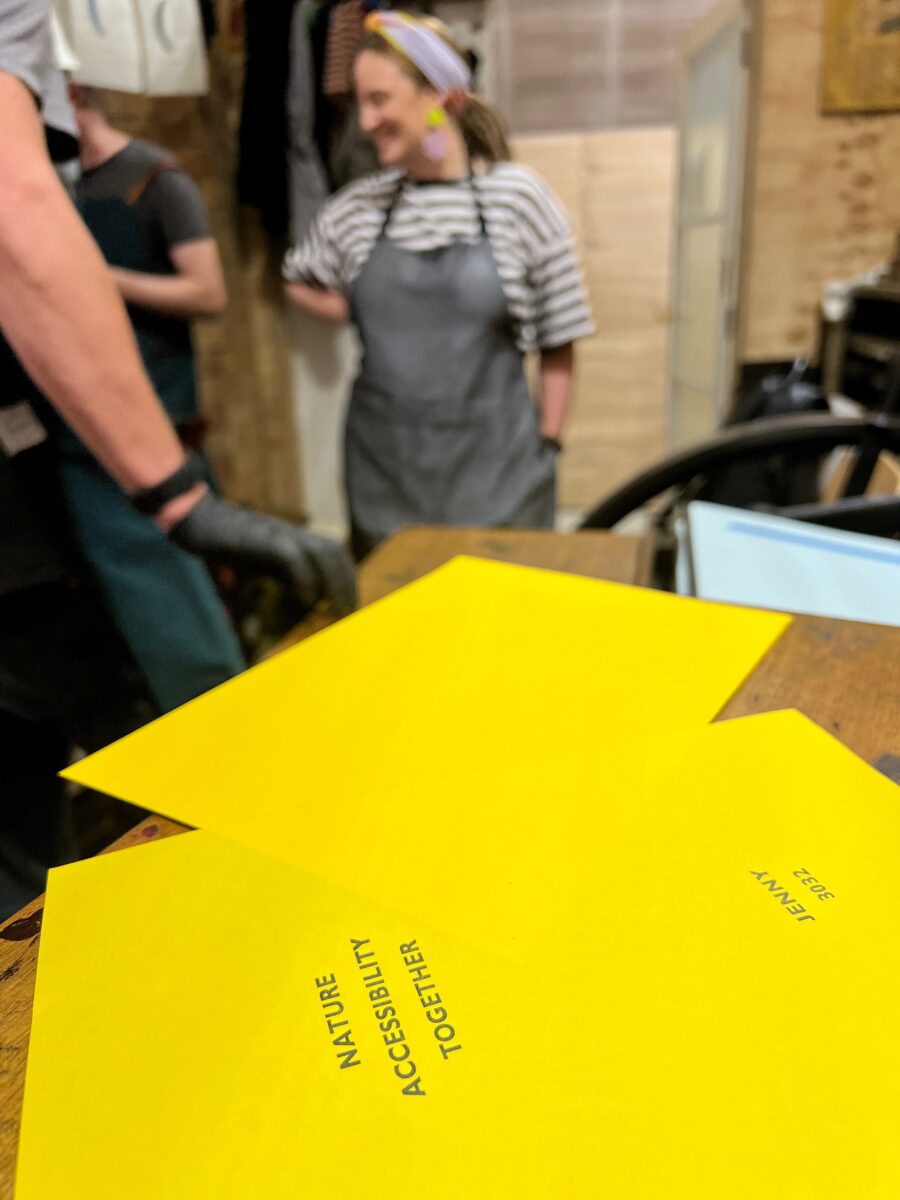

The prompt for the workshop was the question, What makes your local community liveable? We had to write down three words that responded to this. After this, we had to sort through and find letters, so [that included] lining them up in order and making sure that we included our name and our suburb in this mix.

My three words were ‘Fun Street Signs’ and my suburb was West Hobart. We then chose our colour of paper and ink and Neal and Rob got the machines going and printed these for us.

A couple of copies got printed, so we got to take some home and some of them stayed at the studios, and then there was little exhibition and round table that was held later in the week. It was really fun being able to zoom in and watch this online from home, and also being able to connect with the people watching from Geelong. During the round table, we digitally submitted some ideas about where we see the future of our communities heading as well as the future of Commoners Press, and a live printing demonstration was streamed using these words.

I sat down on Zoom with Neal to talk about our experiences at the workshop and the types of artmaking initiatives that Commoners Press are involved with. There’s a real sense of celebrating slowness, and I hope this comes through the conversation, so looking at the very manual process-based technology of the letterpress machines. I think this feeds really nicely into thinking about how we might see a turn towards the hyperlocal when thinking about our own communities and how we might engage with one another through art. We also thought a little bit about public pedagogy and where this could lead us. I hope you enjoy our conversation.

Neal Haslem: So it was great that you could come to ‘these three words,’ Jade. We were excited about putting that on. We didn’t quite know what to expect. It was sort of like, Why don’t we do this idea of ‘these three words’?

I was thinking about how to come up with an activity that would bring people in and that was interesting, but also that would also open stuff up. I’ve got a bit of a history in doing participatory design work and design for community so for me, that interested me. I mean, I love those machines.

Jade Irvine: Yeah. I guess I’d like to hear a bit more about how you came together with Commoners Press. Did that begin with the purchase of the letterpress equipment or did you [and Rob] work together before?

NH: Oh, I’ve known Rob [Eals, co-founder of Commoners Press] for some time. Rob has interests in sustainable practices. His interest in 3D printing connects through to this idea of: Can you take the old technology of the letterpress and then meld it with 3D printing? And also 3D printing with this sense of a change, like a shift in manufacturing or an orientation towards making stuff which becomes hyper-localised. I still work at RMIT now and I’m in the communication design department, but I thought, yeah, that could be kind of fun.

I got drawn into the machines when Rob asked me if I would be interested in coming in because he had found out about this thing [the letterpress machine] being up for sale. And Jan works at the university as well. So he has a background in journalism, but it’s also critical journalism, which is looking at ideas of the commons and alternative economies and effectively a radical critique of societal assumptions or expectations around jobs and work and life. And he does think about ecological sustainability too in his practice. He lives in Winchelsea, which is in the Otways down in Victoria near the coast.

JI: Yeah, nice. You mentioned you were doing some research on community or public learning, what are your thoughts on that?

NH: I’m thinking about this notion of public pedagogy. I don’t quite know how I stand. I mean, I work at a university and I went to a university, but for me, say, working at RMIT in the city campus, I get very excited when things happen outside institutionally-mandated spaces. I mean the institutions provide us with a lot of structure, but they also are businesses.

I suppose with the opportunity that was offered through ‘these three words’, I was thinking well, if people come and the topic is around my future community, like, What do I aspire for my future community? or What are the conditions of my future community? then I was quite excited about that conversation—and the conversation happened a little bit when you [Jade] and the others were putting together your words. So you go, oh yeah, and you come up with three words and that’s a little process in and of itself, but then when you were doing that with others and you’ve got Georgia there and Simon [other workshop participants] and we did that in Geelong the next day, we didn’t have the printing machines, but we could still put the words together. And that was amazing because—it’s a bit stereotypical—but there really were different things coming through about, I don’t know, the sea and different lifestyle orientation.

JI: That was very interesting to hear at the round table, that comparison between Coburg and Geelong and even about the ‘nature’ words and how those were positioned differently. I remember Georgia’s pick of green space, yeah I just wasn’t really familiar with it, but it seems like, yeah, it’s a thing to have like, This is the space, this is the park, this is the area. So that was really cool to hear about everyone’s words and to formally chat about that as well.

NH: That’s great. And so that was exciting to me—having workshops which were manual-making, which produced, I mean, we had to come up with a functioning structure and at the time we were a bit worried about safety, and thinking, How do you allow people to be part of something? but I don’t think we’re gonna train anybody up to use this because we don’t really have the insurance and stuff, but then you are still part of something and then take that experience through into a round table.

For me, I felt like I was very excited about that. I felt like if you make an artefact, what does it allow? I’m very interested in what the artefact allows, and the conversation that is the artefact or that goes into producing it or happens with it, but then where does it take one to? It takes one into something and there’s an externalisation. You came to that workshop and just by picking those three words, that’s some sort of externalisation, which then goes into a mix, which then became part of the round table. So for me, that starts to speak to what I think public pedagogy might offer. There are elements, I suppose, of teaching because people learn a little bit about letterpress.

JI: Yeah, the process and get a bit more familiar with all the steps and the materials.

NH: Really, I think the strong pedagogy is one of collective being and collective becoming. And that sense of ‘not-consensus’—I liked that consensus was not required. But there was this one hour of putting that thing together quite madly, [mimics printing noise] tjuh tjuh tjuh tjuh tjuh and then printing it and going, Here it is, there, you take one, felt really fun and energised to me. When we did that final poster on the Saturday, I absolutely loved that as an activity, particularly the typographic errors. I don’t know why. And it was funny because later on Rob said, Oh yeah, we’ve fixed all the errors and we printed a whole lot more. And I was like, Oh. It doesn’t matter, because I’m interested in how design, and the design and production of artefacts, produce knowledge that we might know, but we don’t know. It sort of reveals or –

JI: – It sort of taps into something that isn’t always on the surface –

NH: – yeah, which might not be articulated. And so it creates this other kind of language and I love that as a collaborative language piece—very simple, but moving into something pretty complex and collective. But we got all the printed samples and then put them up on the wall together and did that as sort of a collective, not as a singular [individual].

JI: Yeah, it’s interesting having so many perspectives and then being able to see that as a whole, but they’re all saying very different things or also there are some similarities. It’s interesting thinking about design in these different ways.

NH: Yeah. And thinking about how, I feel like it’s a little bit like a laboratory where you might go, well, we’re quite interested in this aspect, so we’re gonna strip everything else away and just do some work on that aspect and that shift. And I think also the slowness of it somehow helps that—that it’s going back to what is a slow technology and so in that sense, if you want to typeset the word ‘green space’ or whatever, it’s actually gonna take quite a long time. I mean you can type green, you can write ‘green space’ in a few seconds and you can type it in a second, but in order to typeset it takes quite a while, and then to print it takes quite a while, and what does that enable? I suppose it’s manual production and time spent in production.

JI: It seems very intentional as well. It was nice. I really enjoyed learning about the process and even from filling in the form to start with, and then from then on it was process-based and I think we had some spelling mix-ups in the printing as well, which was kind of fun, ’cause I think they all spoke to something else: Hobrat, Hobat, Hobart—they’re all quite nice.

NH: Yeah, a sort of play on that, an interplay and making mistakes. You could get better and better and faster and faster. There are videos online with people with composing sticks and people could literally, they would just go tch tch tch, and of course, they’re not making any mistakes. Their job is to make no mistakes and do it so quickly.

And yet the affordance of these machines, for us, is that slowness and mistakes are part of the process. And so Commoners Press could almost be about working with an anachronistic, archaic technology to do something slow that is about not speeding it up and making mistakes—and seeing if slowness and making mistakes actually might somehow connect to the value that comes out, and a way of thinking that’s not just about a singular bottom line, but rather a triple bottom line of money, people and the environment. So you’ve got the social and the environmental aspects as well as the economic. But I think there’s something else there, like a creative facility or creative facilitation, and the pedagogy aspect I guess comes more from self-expression, and a sense that there’s something for everybody and everybody brings something.

JI: Yeah, a bit more of an exchange. The sort of human, interpersonal side of it.

NH: It’s quite important. We’re in an interesting space because we are getting better at it. We are relatively inexperienced, but we are getting better. But we have another project going on at the same time called 10Press, with the City of Moreland. And so we got some funding through their Flourish Arts Recovery Grants Program. Basically, it’s a call to people in Moreland who are creative practitioners in some way to submit a work and then we print it.

[The 10Press project] is an act of revealing the creative community, but it’s also activating Commoners Press, and it’s helping us think about what we’re doing there. We are getting better and better, but I don’t want this to be about getting better at the technical printing. That’s not really the point. There are some things and then there are happy accidents and you go, Wow, that looks really cool. Can we do this again? No, we don’t have any idea how to do that.

JI: Yeah, it was interesting hearing about the different types of ink you had as well, and how you won’t be able to get any more of that.

NH: And how the ink was super crusty. I thought, why should we keep that ink? It came as a job lot, the printers and some old stock and the ink.

JI: Right, a package deal.

NH: Yeah. Because what was the old owner gonna do with it? The guy Rob bought it off, he was retiring and he had a little print shop and that was interesting ’cause that print shop was a viable business. He would do job printing and he could make a living doing that. And so he was there, still printing in his late eighties and then goes, That’s it. I’m gonna shut up shop. His business is kind of an anachronism. It’s from another age and we’re kind of carrying that [legacy] on.

Even those inks, when we open them up, we don’t even know what colour they necessarily are; we haven’t opened all of them. But then as Rob remarked, he says, Wow. You use these inks and the colours are all great.

And so Coburg Studios is trying to do something. It’s also just literally people who are creative practitioners, who need somewhere to work and go, If we come together, we can create something you need too, and we’ll take this big factory because the rents are cheaper. And then we just get in more people because the more people who get in, the more viable it is.

So yeah, if you met Andy, who’s one of the principals who set [Coburg Studios] up, it’s not a highfalutin [venture], do you know what I mean? It’s been quite nice having chats to Andy about what we are doing here. And he is very nice. We’re trying to build a bit of a garden out the front and then he talks about the garden being there, and what the garden’s for, and letting the sunlight in; and we’re gonna have this craft market and maker’s market and then we talk about what that might allow.

JI: Is there another exhibition or a book for the ‘these three words’ project? Where is that heading?

NH: We might run another ‘these three words’ workshop with a group of students, and Rob has talked about working, using a similar workshop with different communities.

I’m a little bit careful with it because I still wanted to maintain that sense of that it’s up in the air, that it’s not a product. It’s not –

JI: Bound.

NH: Yeah. We don’t know, to be honest.

JI: Thank you so much for listening. I’m really excited to hear about what Commoners Press has pressed me next and to hear about the further opportunities to reflect, to make things and connect with others in really fun and energising local settings. My name is Jade Irvine and I was joined by the wonderful Neal Haslem. Thanks very much.

Jade produced this podcast as part of Melbourne Design Week’s Design Broadcasters 2022 commission. This transcript has been edited for clarity.