Calculating the cost of womanhood

I first wrote this piece in 2017. I had been writing a lot about the gender pay gap and how the official figure was not just underestimating the problem, it was actually misleading in how little it described the realities of women’s economic lives. I wanted to write a data story about how a lifetime of unpaid and underpaid work had (and would continue to) leave so many older women in real financial danger which can lead to housing insecurity and homelessness. From 2011 to 2016 older women – those aged over 55 – were the fastest growing group facing homelessness, increasing by 31% over that time. This trend has, and will continue to grow, given affordable housing shortage, aging population, and significant gap in wealth between men and women across their lifetimes.

There is no single piece of data that can tell that story. Rather, it is an accumulation of multiple entwined and disparate factors that move in and out of women’s lives from their early school years right through to old age.

I could have written a list of all those factors, cited all the robust, credible sources, their percentage value and the proportion of women they affect, but I doubt there’s many people who would or could read 2000 words of statistics and feel moved by it.

So, instead, I collected all the statistics and used the averages to write a story about how two ordinary, white middle class Australians – John and Mary – can start at the same level in their early 20’s and retire into the extremes of poverty and wealth, solely because of gender. The story starts at their graduation in 2004 and continues to their retirement in 2048. Obviously, we don’t know what economic shocks will occur in the next 30 years, so all I can do to predict their future is use the confirmed data we have to date and project it into the years to come. At every change point in their lives, I have used robust, credible data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics and the Reserve Bank. I’ve used pension, child support and superannuation calculators from credible government sources and listed them all at the end of the article.

I edited and updated the article in 2020, and I will update it again for the post-pandemic period. Unfortunately, I don’t think we’ve hit post-pandemic yet. The data is still fluctuating too much, and we don’t yet know what will happen to wages, jobs, housing, and savings once the world has finished adjusting to COVID-19. The one thing we do know, however, is that nearly one million people under the age of 35 drained their superannuation in 2020. Women in all age groups were more likely than men to withdraw their entire balance under the scheme, and women overall withdrew a greater proportion of their superannuation than men. The effect of this will be catastrophic in the decades to come, and so far, no one has a plan for how we will deal with this.

Note: There is no robust data on the pay gap for women of colour in Australia. Data from the UK and the US shows significant differences in pay between white women and women of colour, and it’s almost certain we have the same issues here. We collect gender pay gap data because you can’t fix a problem you can’t measure and it’s telling that we don’t collect data on the ethnicity pay gap. Without that data, it’s not possible to include race as a factor in this story – but it should be.

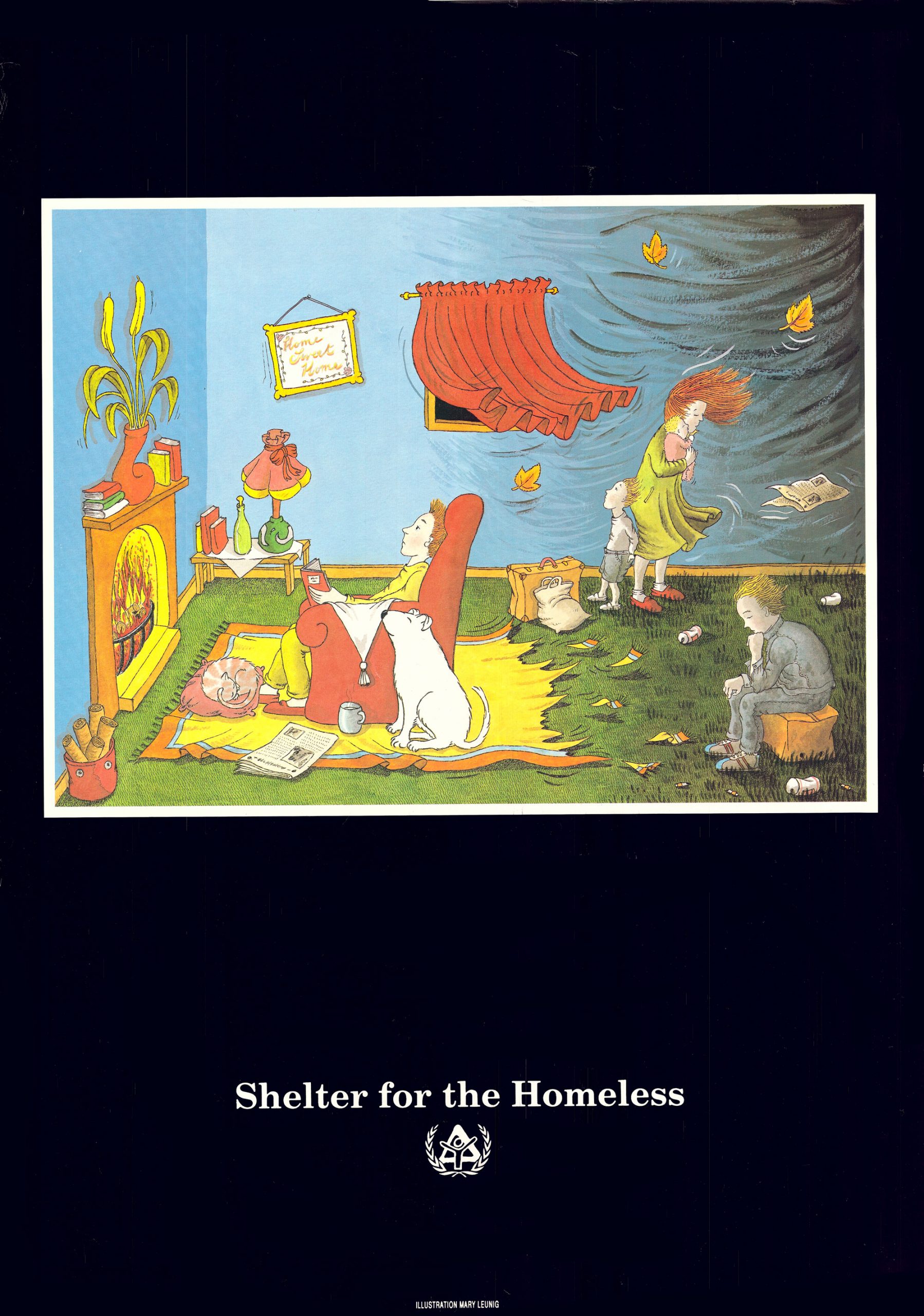

“I did this poster during my time as an artworker at Trades Hall from 1987 to 1989, working alongside art director Megan Evans and artworker Julie Montgarrett. My salary from Trades Hall was about $200 a week, which paid the weekly rent in Carlton exactly. The United Nations had just recognised 1987 as the International Year of Shelter for the Homeless. The brief for this illustration was to think about how homeless people aren’t what people think – men in doorways that The Salvation Army takes care of. It could happen to anybody, women and children included – and through a whole lot of bad luck often.”

– Mary Leunig

John and Mary were born in 1981. They met at university and both graduated in 2004 when they were 23 years old. They both found work soon after graduation, John’s graduate accounting job paid $36,000 per year and Mary’s admin job paid $32,000 per year.

At 28 they married and were both promoted. John’s salary had increased to the average1 for men in finance – $80,000 per year. Mary continued her work in administration and her salary had only increased to $35,000 per year

They had been saving to buy a house and both sets of parents gave them $15,000 each towards a deposit. Houses were too expensive, but they found a nice two-bedroom flat close to the city for $350,0002.

When they were 30, Mary got pregnant, and John got another promotion. His salary had increased to $92,000. Mary’s employer offered her 18 weeks paid maternity leave and a guarantee that she could come back to her job after 12 months.

When it was time for Mary to return to work, they decided they didn’t want their baby in full time childcare. They calculated the cost of childcare and measured it only against Mary’s salary, because John didn’t want to reduce his working hours and risk losing another promotion. They decided that Mary would return to work for two days a week, which would earn $15,000 per year and just cover the cost of childcare and her travel.

When they were 33, John got a new job and his salary jumped to $96,000 per year. Mary was earning $16,000 a year.

The next year they sold their apartment and bought a two-bedroom house in the suburbs for $900,0003. Mary got pregnant again just after they moved. When the baby arrived, they calculated the cost of childcare for two children under five would be almost as much as she could earn working two days a week.

Also, John was spending a lot of time at work, and they were struggling with running a house and caring for two children. They agreed the best solution would be for Mary to stop working outside the home so she could take on all the domestic work, which would leave John able to concentrate on his career and increase the family income.

By the time the third baby was born, they were both 37. John was still earning the average salary for a man in the finance industry, which by that time was $104,000 per year. Mary had no paid work and had made no superannuation contributions.

For the next five years Mary stayed home with the children. John continued to work full time. Assuming a conservative salary increase of 1.5% per year4, his salary by the time he reached 40 years of age would be $108,00 per year.

Sadly, the year John and Mary turned 40, both Mary’s parents died. They left her some money which Mary used to pay out just over half of their mortgage.

When they were 43 and all the kids were in school, Mary got a casual job as a receptionist in the local medical centre for 20 hours per week, with no paid holidays or sick leave. While her starting salary was $19,000, as it had been ten years before, John’s salary had increased to $113,000 per year.

By this time, John and Mary had started drifting apart. They were fighting a lot and John was often absent. Mary thought he might be having an affair. She was lonely and felt that he didn’t notice how much work she did to care for him and their children. John felt that she had no understanding or appreciation for how hard he worked for the family.

John and Mary separated when they were 46. John’s salary was $118,000 by then. Mary was still working 20 hours per week at the medical centre, her salary was $20,000.

After selling their house for $1.2 million and sorting out their remaining $550,000 mortgage, they both had $325,000. John’s superannuation balance at the time was just over $280,000, while Mary’s was $67,000. As part of the settlement, she received $75,000 of John’s super balance. Her lawyer advised her that she could go to court and argue for a larger portion from the sale of the house, because her inheritance had been used to pay down the mortgage. John disputed the claim, because he had contributed a higher amount to the mortgage repayments. Mary couldn’t face the emotional or financial cost of a drawn-out family court dispute, so she agreed to John’s terms5.

The children stayed with John one weeknight and every second weekend but stayed with Mary the rest of the time. John paid Mary $20,000 per year in child support for all three children.

Mary took on more hours at the medical centre, which increased her salary to $25,000, but she still had no paid leave.

John used his share of the money from the sale of the house and bought another home for $1.3 million. Mary couldn’t get a mortgage because she only had casual work and she couldn’t afford repayments on a house big enough for her and three children. She put the money in the bank. She knew she should probably invest it somewhere, but she wasn’t sure where and she didn’t want to have it locked away because she often had to draw on it to pay rent6.

At 52, John’s parents died. He used his inheritance to pay out his mortgage and then started adding $25,000 per year to his superannuation balance, which he was able to do because his salary had gone up to $130,000, he had no mortgage or rent to pay and his two oldest children were over 18, so was only paying child support for the youngest child.

Mary was still working at the medical centre. Her salary had increased to $27,000 but her rent had gone up and she had to move house twice. Her income was not enough to cover all her living expenses, so she was still spending the money she got for the house after the divorce. The balance had dropped to $250,000.

Two years later, Mary lost her job when the medical centre was sold. Her two youngest children were still living with her, so she needed to rent a two-bedroom house. She was eligible for unemployment benefits but needed to keep drawing on the remaining money from the sale of the house to cover her living costs.

Mary never got another permanent job. Despite having a degree, she had spent too long out of the workforce and her job at the medical centre didn’t offer opportunities to increase her skills or get promoted. She got a few causal jobs through a temp agency, but most employers wanted younger workers for clerical jobs, and that was the only work she knew how to do. She got around $350 a week from Centrelink, and John was still paying $280 per week in child support for the youngest child.

When they were 55, John was earning $135,000 per year. Mary still didn’t have a job and John no longer needed to pay child support because all three children were over 18. The youngest child was still living with her. She moved to a two-bedroom flat and continued to use the money left in the bank to cover the difference between Centrelink payments and living costs.

After a lifetime of hard work, John retired at 67. His superannuation balance was $1.376 million. He owned his home and received around $65,000 per year from his super. He also had shares and other investments he picked up over the last ten years. He will be financially secure for the rest of his life. After a lifetime of hard work, Mary had almost nothing left from the sale of the house and her superannuation balance was $425,000, which, with top up from the old age pension, paid her around $42,000 per year.

She was renting a one-bedroom flat for $400 per week, which left her $350 a week to cover all her living expenses, including food, bills, clothes, health care, transport, insurance, internet, and entertainment. She was in housing stress at retirement and has no prospect of ever being able to change her financial circumstances. She will live in poverty for the rest of her life.

Addendum: If John and Mary were born in 1990, they would have been 30 years old when the pandemic hit in 2020. If Mary had withdrawn the full $20,000 from her superannuation then, as she would have been allowed to do, and assuming nothing else about her life changed, her balance at retirement would be about $303,000. This would drop her income by just over $100 per week less than she would have had if she had not taken that money from her superannuation when she was 30. This is the future of all the women who took money from their super in 2020 – and that’s without factoring in the economic shocks yet to come.

Further reading:

- A study of the earnings of new graduates in their first full-time employment in Australia covering 1977 to 2004. Graduate Careers Australia, 2004. Graduate Starting Salaries 2004.

- Child Support Australia, 2021. Child Support Calculator/Estimator.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2019. Marriages and Divorces, Australia, 2019.

- Australian Super, 2021. Super Projection Calculator.

This story was produced for our issue #14 Work. To grab a print copy (and pay only postage) head over to our shop.