Architects Tristian Wong and Jefa Greenaway on redefining “Australian” architecture

In INBETWEEN, the exhibition selected to represent Australia at the 17th Venice Architecture Biennale, Australasian architecture takes centre stage. Curated by Jefa Greenaway, a Wailwan and Kamilaroi man and director of Greenaway Architects, and Tristan Wong, director at SJB; the installation offers a filmic response to the Biennale’s theme: “How will we live together?”. A central film showcases a series of public architecture projects that celebrate cultural connection – with the environment, with heritage, and with the greater world at large.

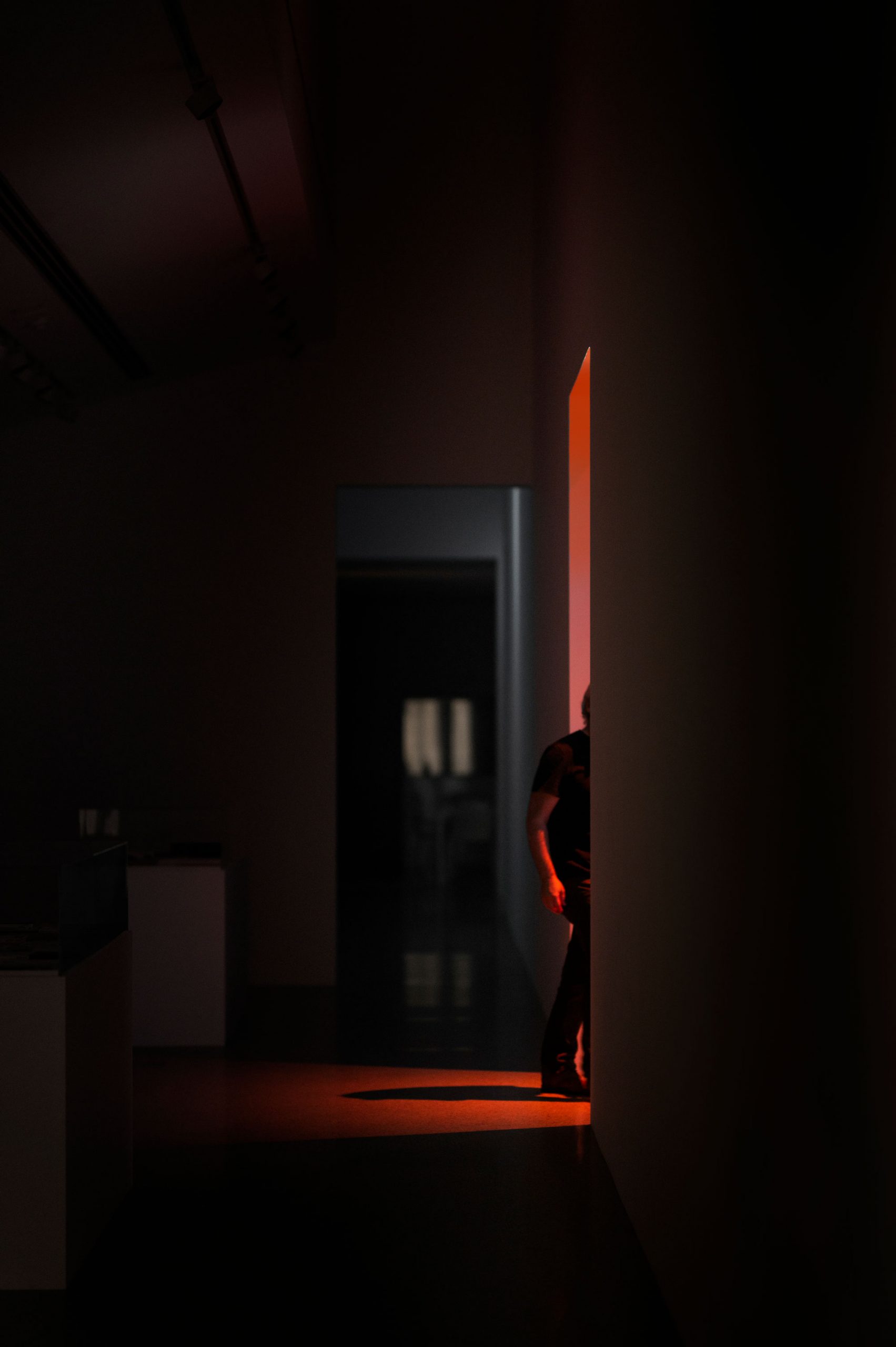

For Greenaway and Wong, the Biennale’s theme provoked them to consider Australia’s location “in between” countries in the Pacific. As a result, blueprints, renders and photographs of projects from around Australia and our nearby Pacific neighbours, including Aotearoa New Zealand and Papua New Guinea, flit across the screen against an atmospheric soundtrack of fire crackling and birds in the background. Blurring the line between the built and the natural environments, the resulting experience feels uncannily like floating outdoors amongst a river of architectural projects.

Initially intended to be exhibited in 2020 – but delayed due to pandemic restrictions – INBETWEEN took two years to create. Conceived as a projection onto a sphere within the cubic dimensions of the Australian pavilion, Greenaway and Wong will also tour and exhibit INBETWEEN as a film locally in Australia – a first for an Australian exhibition since its first Biennale pavilion in 1988. Annette Lin spoke with Greenaway and Wong on the challenges and opportunities of working on the project during the COVID-19 pandemic, and what it heralds for the future of Indigenous and non-Indigenous architectural practice on colonised land.

Annette Lin

So this question might be really obvious, but how did the pandemic affect INBETWEEN? In some ways it seems like it might have opened up different opportunities and possibilities, would you say that’s correct?

Jefa Greenaway

We feel in some respects that the pandemic has actually strengthened the ideas in INBETWEEN. We responded quite directly to the original Venice Biennale theme of “How will we live together?”. Our idea of “in between” is really looking at the space between a number of different dimensions: the space between identity and place; anchoring in Country; some of the global challenges around climate change; and understanding the context of our broader region. We wanted to give expression to the process and journey of how architecture can speak to identity and culture. And despite this being an extended experience over two years, rather than one year, in many respects, the content couldn’t be more relevant – the last year has actually amplified it.

Tristan Wong

Exactly. It’s been a really tumultuous last year or two, with COVID-19, Black Lives Matter, and environmental challenges: rising sea levels, global warming, bush fires. The themes and the narratives of INBETWEEN dovetail really well into all of these things. The overarching theme of the Venice Biennale is, “How will we live together?”. We’ve got challenges around cultural identity, Black Lives Matter, environmental challenges and the COVID-19 response, so how do we live together in this context?

How do we live and work together? How do we harmonise cultural dimensions that exist between First Nations people and non-Indigenous people? And how do we create projects that are really layered and give voice and agency to Indigenous people whilst also existing in a very contemporary context?

AL: Do you see INBETWEEN as part of a bigger shift in consciousness? And how do you think people – both within and outside the architecture industry – can build on that?

JG: Well, in some respects, the starting premise is to acknowledge that all projects built in the Australian context and within our region are built on Indigenous lands. And if that’s the starting premise, then everyone has a responsibility, an obligation and an opportunity to engage with the complexity of how we engage and anchor in Country.

Within the pre-colonial Australian context, there are over 250 distinct languages, and over 450 languages within our broader region. So, what that talks to is diversity. It talks to complexity. It talks to the fact that culture isn’t monolithic or homogenous.

As a result, all the projects in INBETWEEN give voice to the layers beneath how we actually go about a culturally responsive design practice. The projects we chose, and the diversity across our continent, demonstrate how practices are grappling with some of these complexities across different scales and project typologies. Some are quite modest; others are much larger in scale and ambition. But the same threads run through – the way they develop and build a process and a methodology.

AL: From arts centres in the Pilbara to ranger accommodation in the Northern Territory, there’s quite a diversity of projects. Can you speak more about the process of sourcing and curating the projects you included in INBETWEEN?

JG: There was a national call out, which we then expanded beyond our shores. What we wanted to do was explore a number of different dimensions and to see how the various projects mapped to our thematics of sustainability, identity, and Country or place, and see that these projects understood those dimensions within their own projects.

We also created a cultural reference panel, to ensure that we had a level of cultural authenticity embedded as part of the curatorial process. We managed to get projects from every state and territory in Australia, as well as across other nations within our broader region as well. But the focus wasn’t really around hero-ing the individual practices, it was more about: how do these different projects support a bigger story and conversation?

TW: Exactly. It was actually about trying to convey and elevate the processes – the methodologies, the levels and layers of engagement these practices went through, the conversations they had with communities, the language groups and the Elders that informed those decisions and those projects.

We also managed to include some somewhat very humble projects that might otherwise never have been published. Some of the projects we chose for INBETWEEN are big civic projects, and that’s fantastic. But there are also smaller projects, in quite remote locations, that affect people in a powerful, positive way but that ordinarily wouldn’t get a lot of exposure. These are buildings that are built for communities. And that’s really important because it demonstrates the power of architecture to affect people in different ways – not just in urban environments but in remote environments too, and not just on a large scale in the civic, urban realm, but also in smaller communities.

That’s the relevance of good architecture – that it makes an impact in a positive way, across all of those different dimensions, contexts and landscapes.

How do we live and work together? How do we harmonise cultural dimensions that exist between First Nations people and non-Indigenous people? And how do we create projects that are really layered and give voice and agency to Indigenous people whilst also existing in a very contemporary context? — Tristan Wong

AL: How do you think urbanism and architecture can be used to embed Indigenous knowledge within a wider Australian cultural context?

JG: In many respects, one of the elements that we sought to communicate is that as architects, urban designers and landscape designers, we all operate within a social contract and a social license, and that comes with certain obligations and responsibilities.

If we start to think and consider the urban environment in which we practice – the layers of history and meaning of that place – we can start to give voice to that. We can make the invisible visible through engaging with Traditional Owners, knowledge keepers, Elders and custodians, and these stories and narratives can start to be embedded as part of the way in which we engage.

It’s the simple idea of starting with a conversation and having the right people in the room, and carving out the time and space to have that meaningful engagement. That way you can obtain the requisite cultural knowledge to proceed with the project, adhere to cultural protocols, and what you’re essentially doing is talking to our explicit First Nations experience.

We asked the various participants who responded to the call out, on which Country is your project located? If they didn’t know, then it potentially demonstrated a cultural blind spot. What that reinforces is the role and necessity of developing a process which speaks to the complexities of practice in the Australian context and beyond, particularly on the back of some of these broader global movements. The time is now to have these conversations. In Victoria, for instance, we’re seeing developing legislation for a treaty, we launched the Yoo-rrook Justice Commission on the 14 May this year. There’s a First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria. So in a way, through the film, we’ve captured the pulse of what practitioners are doing now.

TW: There’s so many layers of history of recognising and acknowledging Country and Traditional Owners and storytelling. These things can be embedded into projects that give them a much more layered dimension. First Nations people have lived on these lands in the Australian context for some 60,000 years, touching the land lightly, understanding preservation of land sustainability, doing all of this as part of their daily life and ritual. Are there things that we can learn, as architects, landscape designers or creatives? Whether they’re construction techniques, site building orientation, water preservation – there’s a whole lot of potential for contemporary architecture to learn from what First Nations people have done on this land for generations. These things should be, and can be, layered into our own practices.

AL: Agreed. What are your thoughts on how we put it into practice? Jefa – you lecture at The University of Melbourne. What role does education have in bringing these ways of working and understanding in?

JG: I think the start of these conversations should ideally occur through design education. Invariably, many of those who are practicing now weren’t privy to even having these conversations – it wasn’t part of our experience through learning about and developing our skills as practitioners through university. But there has certainly been a shift in recent times where there is an impetus to decolonise or, or Indigenise, design education.

And how can one start to do that without engaging and understanding our deeper history? Why would we not draw upon generations of wisdom? Why would we not connect to and engage and try and understand the relationship to Country?

Why wouldn’t we not want to seek to explore and understand Indigenous knowledge systems? Why would we not want to understand the diversity and complexity of language, of narrative, of sustainability through a cultural lens as informing the way we think about design teaching? That process of knowledge exchange – of Indigenous and non-Indigenous knowledge systems coming together – can coexist.

This content was produced in partnership for our issue #14 Work, with our friends over at Open House Melbourne | Centre for Architecture Victoria and produced ahead of their 2021 online program Reconnect. To grab a print copy (and pay only postage) head over to our shop.