Liam Young on envisioning our collective futures

When we think of our futures, tumbleweeds blowing across water-starved desert landscapes or rain-washed dystopian inner-city streetscapes spring to mind. It may feel like a climate apocalypse is all but inevitable, but are we too quick to default to hopelessness and dystopia?

Australian-born speculative architect Liam Young’s Planet City – his most ambitious project to date – brings together thinkers in fields including ecology, emerging technology, economics, political science and Indigenous storytelling. Collectively, they speculate on how the entire human population could live together on just 0.02 percent of the world’s surface. The first phase in this long-term project is a large-scale film accompanied by a book of essays, commissioned by the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) for the NGV Triennial 2020, shown in Melbourne from 19 December 2020 until 18 April 2021.

Young’s work occupies this sticky space between reality and fiction. With his urban futures think tank Tomorrow’s Thoughts Today and the award-winning nomadic workshop Unknown Field Division, his research-based practice is a continuous interrogation of the present realities of cities to imagine future urbanisms. Annette Lin spoke with Young in June 2020, while he was in the midst of production in Los Angeles, about how storytelling and design can be used as tools to agitate our collective imagination and provoke us to realise that we have agency over our futures.

Annette Lin

What brought you from architecture, traditionally considered as the practice of developing buildings, to creating stories that contain speculative futures for our cities?

Liam Young

Early on in my career, I realised that forces shaping the city existed well beyond the traditional remit of architects. Our cities used to be shaped by buildings, public spaces and large-scale fixed infrastructure – all the things that architects had the capacity to engineer. Now the forces that shape cities are planetary scale networks and invisible infrastructure, like mobile networks which we carry around in our pockets.

My work slowly started shifting away from more traditional, high-profile, iconic building-making activities and towards time-based systems, software and cultures of city making. I wanted to tell stories of cities and the ways they are shaped by forces that exist outside of the built spectrum.

AL: In light of that approach, can you tell me about your most recent project, Planet City?

LY: Generally, when we think of the future, we see neon lit streets, the rain of a collapsed climate, technology out of control, and big mega corporations running the city. What many don’t realise is that this is our present. Planet City imagines the necessary lifestyle and cultural changes needed in order to dig us out of this hole. It is a long-term research project involving many people from different fields to form an antidote to the narratives about the city produced by Hollywood, Silicon Valley and the international news cycle.

“As of today, we have created a planetary scale urbanism where every square centimetre is touched by urban development. From that perspective, we are all citizens of one city already.”

AL: Does the premise of Planet City come from the idea that if we could condense our footprint into a smaller physical space, we could let the earth heal from the ravages of human-made climate change?

LY: Yes. The prominent biologist Edward O Wilson developed a theory called Half-Earth, which proposes that human development should be contracted to 50 percent of the planet, and the other 50 percent should be returned to nature, to wilderness, and allow it to recover.

The architect in me considered a city on 50 percent of the earth and thought, “Boy, we can do much better than that.” So, the city we imagine is on 0.02 percent of the earth’s surface, not half of it. We researched the densest urban constructions on the planet. For example, Manila is currently the densest city in the world with 42,857 people per km2, and a total of 1.78 million over 42.88 km2. If all 7.594 billion of us could live together at that density, then the city would only have to be the size of Melbourne, Sydney or Los Angeles.

Through this provocation of a single city, we present different ways that we might be able to live more compactly. How could such a city be a self-sustaining organism? Could we think of it as a closed-loop system that doesn’t flush huge amounts of waste, out of sight and out of mind, into a distant landscape?

AL: How does the work make the argument that we should live together like this?

LY: As of today, we have created a planetary scale urbanism where every square centimetre is touched by urban development. From that perspective, we are all citizens of one city already. This is a city dispersed and distributed and atomised across the entirety of the earth. With Planet City, we hope to address a new model of citizenship.

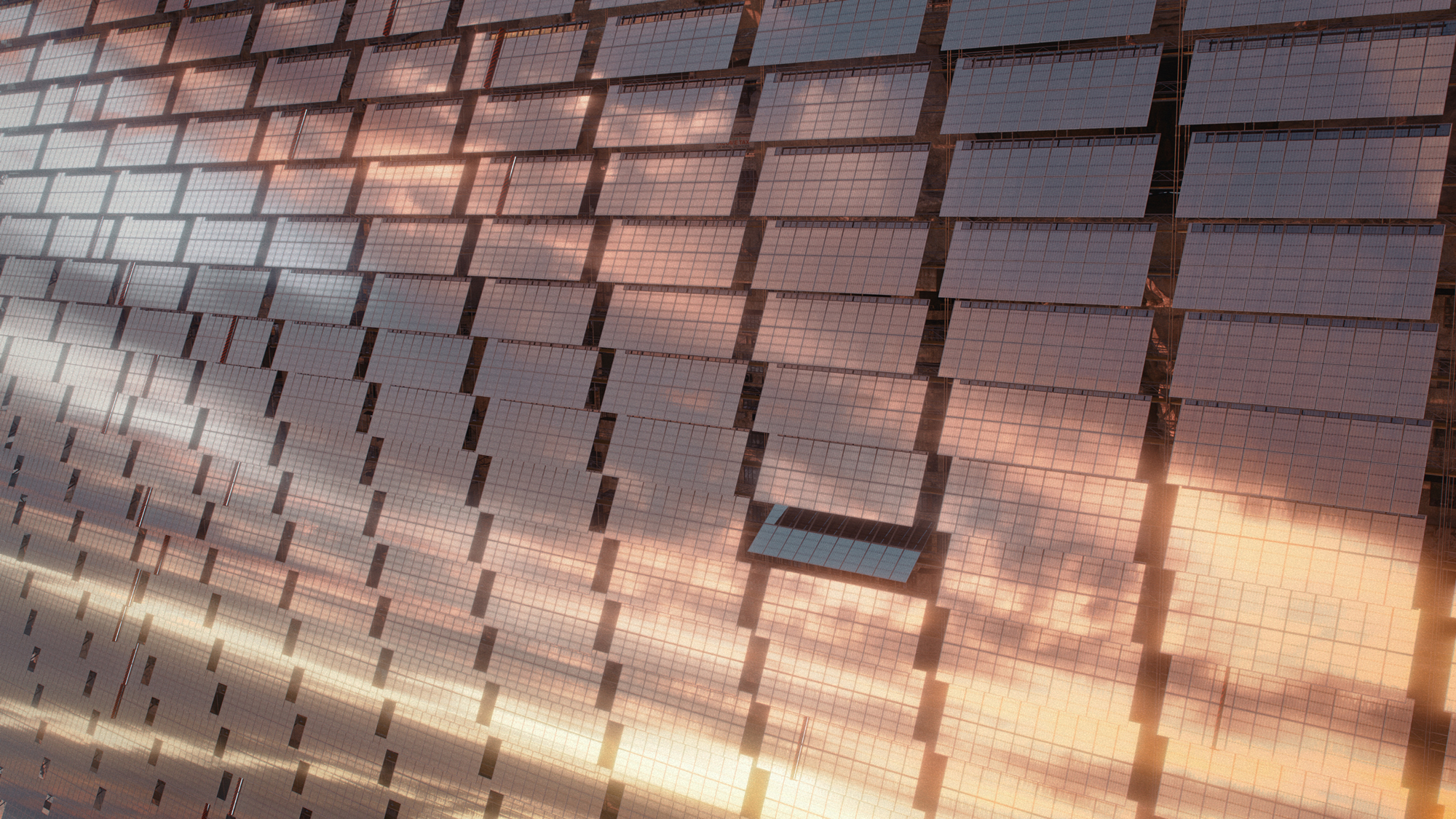

Planet City also has the capacity to act critically and not just as a fantasy, because it’s built entirely from technology that’s already here. Climate change is not a technological problem anymore – we have the know-how to mitigate further damage to the environment. What we’re missing is the political will and the cultural engagement required to sufficiently invest in these technologies.

All of the technological systems that power, run and manage Planet City are based on present-day technology, just re-purposed and scaled up. That’s not to say that this is a solution; that we all move to one city and everything’s going to be okay. But it’s a provocation to get us thinking differently.

AL: How did you work to base the fiction of Planet City in reality?

LY: What the world doesn’t need is another future city envisioned by the singular genius, a white-male expert. We didn’t want to have any preconceived notions of what the city would look like. So, at the start, we formed a council for Planet City, with some of the most celebrated international scientists and theorists from around the world who are developing the sustainable technologies we needed.

We talked to Kenneth Nealson, a NASA biotechnologist who is developing a closed-loop waste system for Mars habitation, about how those same systems might be used in a city like Los Angeles. We have been talking to Lucy Chinen and Sean Raspet, the founders of algae food startup Nonfood, about how we can replace our predominantly meat-based diet (the food system for which is not sustainable given its heavy dependence on energy, land and water resources) with proteins from algae. Authors such as Benjamin Bratton have contributed to the Planet City book with texts exploring urban scaled artificial intelligence (AI) and forms of algorithmic governance. Environmental technologies researcher Holly Jean Buck has written on the geoengineering and carbon capture processes that the city sets in motion. We are trying to be inclusive and to think about the narratives of the city that present an alternative to neo-colonial models of extraction and exploitation. Aboriginal Australian writer and director Ryan Griffen wrote a science-fiction story set in the city that speculates on how Indigenous communities might respond to this emerging context and we have interviewed experts such as professor of folklore and ethnomusicology Gregory Schrempp to discuss the cultures and mythology of this city.

I’m really just acting as a sort of curator of conversations that come together to form a city made through the collective intelligence of the council.

There is no one ‘future’; there are futures. It’s that plurality that gives us a critical edge.

AL: There is a duality between science fiction, which is often dystopian, and the utopian future that technology companies out of Silicon Valley communicate. Where does this work sit in relation to that?

LY: Yes, the tech sector thrusts upon us solutionist relationships to technology, while Hollywood is really good at selling the dystopian narrative with cautionary tales.

It’s a critical role of the speculative architect, as I often call myself, to make and put into the world counter-narratives about technology. The work that we do isn’t explicitly dystopian or utopian. We try and sit between those views and say, “Hey, it’s actually much more complicated,” and through this we make space for the unintended and less well-trodden narratives. There is no one ‘future’; there are futures. It’s that plurality that gives us a critical edge.

We’re not in the business of prediction. The great cliché of science fiction is that it’s about the future, when it’s actually about the present. George Orwell’s novel 1984 is not about 1984, it’s about 1948, the year in which it was written, and our work shares that same sensibility. What we’re trying to do is present and prototype possibilities. The test of these speculations is not whether we get it right, but whether or not they instigate positive and interesting action in the present moment.

AL: Why is the first outcome of Planet City a film? What do fiction and storytelling through film offer that physical buildings do not?

LY: Emerging technologies are shaping cities faster than architects are able to respond to because building is a laboriously slow and financially complicit model. I call all these technologies – drones, driverless cars, Smart City technologies and algorithmic governance to name a few – ‘before culture technologies’ – they arrive faster than our ideological capacity to understand what they mean. Architecture is a discipline on fire. The traditional form of the architect is becoming increasingly niche, and increasingly a tool of a wealthy elite. We’re in the service of capital, in the service of luxury. Fiction is a critical operative strategy which allows us to prototype new cultural relationships to these technologies at the pace in which they are being released. There must be different ways that architects can operate with a new kind of critical urgency, and film and storytelling is just one of them.

Film is very accessible; we all have a literacy with film that we don’t have with urban master planning drawings or cross sections and architectural plans. There’s a real power in the way that you can encode architectural and urban ideas into film, almost like Trojan horses, and connect audiences with those ideas. We then hope through watching, audiences can feel more empowered to make decisions about their futures.

With the first film produced as part of the Planet City project, we co-opted the Hollywood mechanisms of visual effects, costume and science-fiction narrative. We worked with the costume designer Ane Crabtree, who designed the iconic red dresses from the TV adaptation of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, to tell a different kind of story. The film shows a moment of celebration within the city, a carnival. Instead of repeating the visions thrust upon us of dystopian cyberpunk cities out of control, we want to present futures where we see ourselves living very differently, but it’s positive and aspirational as opposed to cautionary and destructive.

The future fiction of an imaginary world is a new kind of site, and we’re using that as a way to prototype all these shared ideas about what our futures could look like. We hope through this, we may be all able to come to more of a shared consensus about how we want to live together.

This piece is part of Assemble Papers 13 Mind the Gap, published at the beginning of February 2021. Find the print version of Mind the Gap at cafes across Melbourne, or order a copy from our webshop and pay only postage costs.