Ahakoa He Iti He Pounamu*

In the heart of the far north of Aotearoa New Zealand sits the small farming town of Kaikohe. Often referred to as the centre of local iwi (tribe) Ngāpuhi, whose hapū (smaller tribes) spread all the way to Cape Reingā, the area is steeped in Māori history. Rolling farmlands that surround the small town are punctured with impressive volcanic cones marked with pā fortifications, architecture built by Ngāpuhi to protect against incoming war parties. Their presence indicates the density of the Māori population 500 years ago and invokes a long tradition of design and making.

State Highway 12 now intersects the town centre, carrying travellers between the east and west coasts near the northern tip of the island. A period in the 1980s hit the already declining town’s working population hard. ‘Rogernomics’, a term coined to describe the neoliberal economic policies followed by the then financial minister Roger Douglas, saw financial market deregulation, tariff elimination and the privatisation of public assets and services. Almost overnight, it put people in small rural towns around Aotearoa out of work, Kaikohe included. That and the discontinuation of a major railway link meant a slow decline for the town. Today the population is just over 4,000 people, 78 percent of whom identified themselves as Māori in the 2018 census.

“Our name represents the energy created by bringing things together. We bring ideas together, we bring communities together, we bring people together.”

Now ĀKAU, a vital design practice, is working to empower the taitamariki (youth) of Kaikohe to have a say in the future of their town. Designer Ana Heremaia moved to Kaikohe in 2014 after a stint in London working in architecture practices. With her whakapapa (ancestry) present in the local area, she was searching for a way to connect to her roots and give back to the community through her design knowledge. Heremaia co-founded ĀKAU with architect Felicity Brenchley and designer Ruby Watson, both based in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland.

Initially, the trio thought they would be designing furniture and manufacturing it with skilled locals. They soon realised the design process itself held much more valuable engagement than manufacturing objects. Heremaia explains, “We now see ourselves at ĀKAU as a connection point between the community and the design profession.” It is a practice in motion; their kaupapa (approach) is constantly growing and shifting. Nevertheless, the projects so far are intrinsically linked to the people and the place in which they are situated. Their name captures this well. In te reo Māori, the Māori language, ākau means the place where water and land meet. “Our name represents the energy created by bringing things together. We bring ideas together, we bring communities together, we bring people together,” says Heremaia.

Social enterprise as an organisational model is yet to take off in Aotearoa, so ĀKAU doubles as a design studio and charitable trust. The studio works on architectural projects which aim to have a lasting impact within the community, while the charitable trust focuses on engaging community into the process of design and making through a Te Aō Māori (Māori world view) perspective. Brenchley explains, “Any profit we make in the studio goes to providing our design services to projects and people that wouldn’t ordinarily be able to afford it or to support our taitamariki education programs.”

ĀKAU’s studio sits just off the main road, close to the centre of Kaikohe. It is a porous space, activated by people coming and going; a workshop with local school children one day, and designers working on ideas for public space the next. While the studio is a busy hub of activity, it can be hard to get projects off the ground. “People are innately creative here, but design as a profession has taken a while for people to understand,” explains Heremaia. “There has been consultation for decades by council and government for what people would like to see in their community, but with no deliverables,” she continues. “So, understandably, there is consultation fatigue, frustration and a lack of confidence.” In the beginning, learning through doing with small-scale projects was an important approach to increase design literacy and grow trust for ĀKAU.

“Hopefully, through learning the design process they build confidence, learn more about themselves, and see that they are contributing to their community.”

Bling Bling Toi Marama, ĀKAU’s biggest temporary project to date, went ahead in July 2020 during Matariki (Māori New Year). Many locals had commented that Kaikohe didn’t have enough streetlights in their town, and that they didn’t feel safe at night. ĀKAU collaborated with Te Pū O Te Wheke Community Gallery and Arts Trust, holding workshops to bring the dark streets to life. Glowing art was created by more than 250 children to create the installation Te Ana Marama (The Light Cave). Tangaroa, the god of the ocean, came to town with schools of bright fish floating around him. Installed in a disused site in the middle of the town, Te Ana Marama brought together more than 2,100 locals (over half of Kaikohe’s population) during the three-day festival.

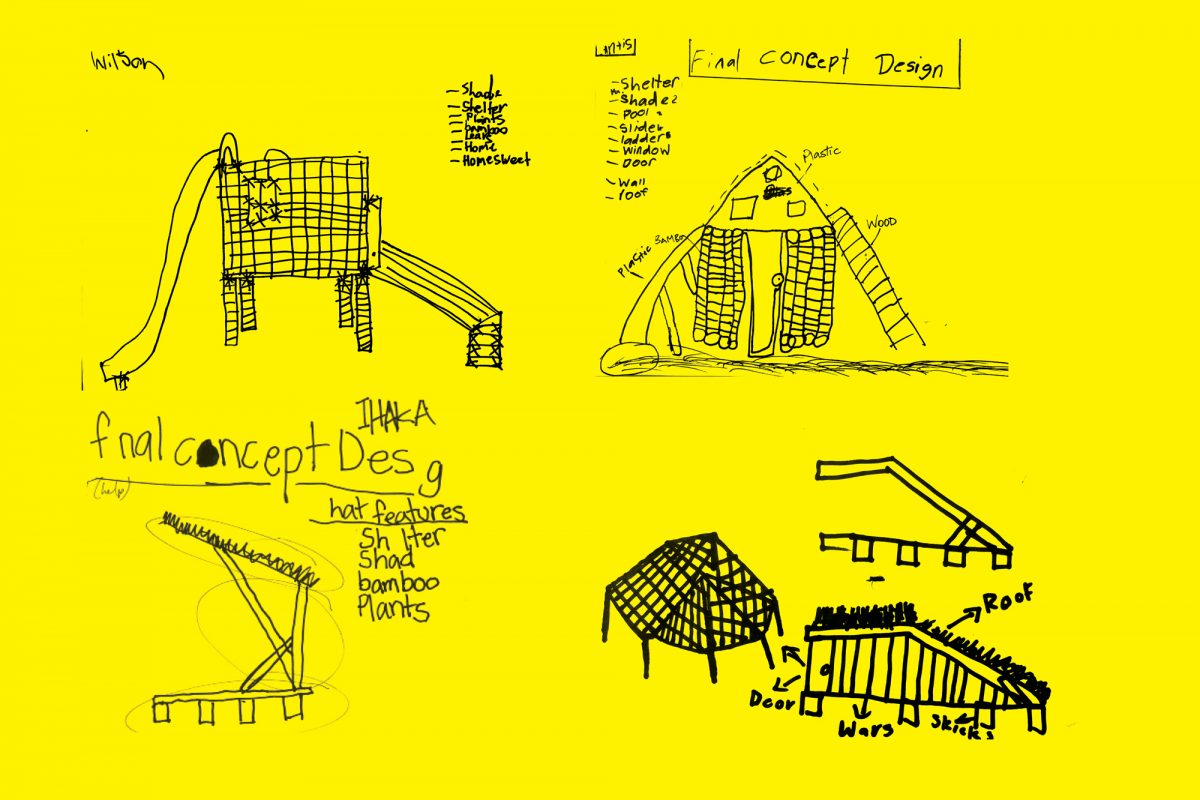

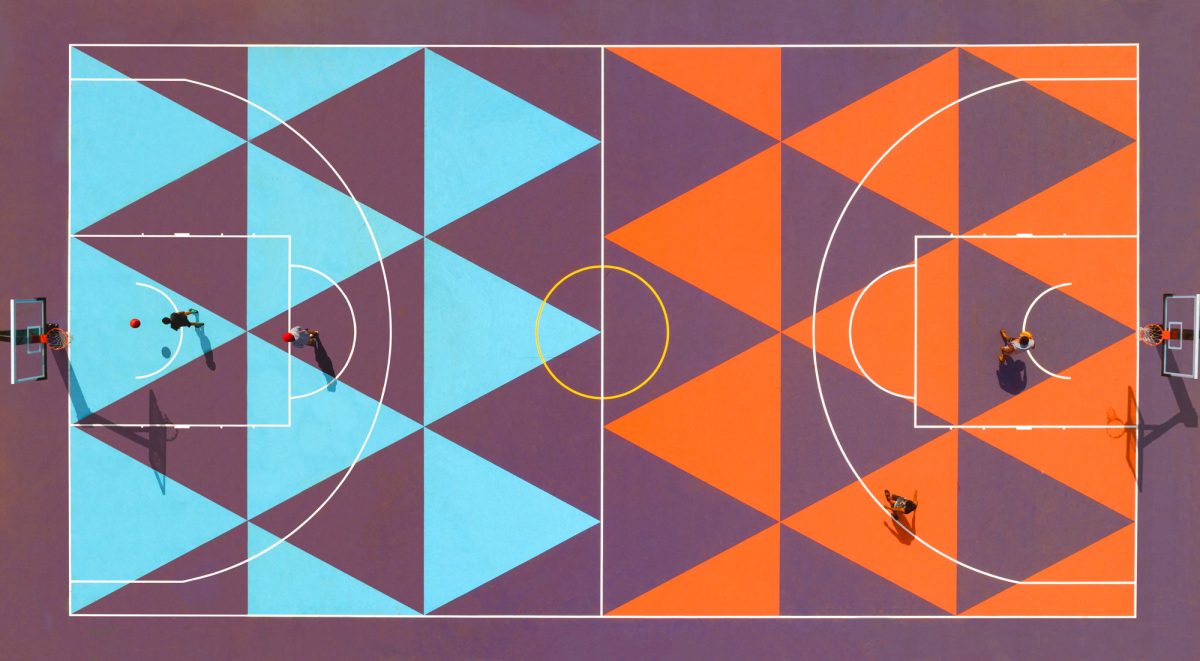

“We do these smaller interventions, which are slowly growing in scale and permanence, in the hope we will finally get some of the larger infrastructure projects over the line,” says Heremaia. ĀKAU advocates for the community to council and recently had plans approved to continue an ongoing project – a landscaped park in the centre of the town. The project started out with a basketball court, driven by the local Kaikohe community and kōtiro from Kaikohe Intermediate, with ĀKAU engaged to do the design. Working with a group of community members, ĀKAU designed a colourful niho taniwha (pattern of teeth-like triangular panels) graphic. It speaks of mahitahi (the power of working together) and leadership. With the basketball court now complete, the next step is to design a whānau area for families to sit under shade and cook and eat together, a learn-to-bike track for kids and an outdoor exercise zone with the development of the skate park and playground.

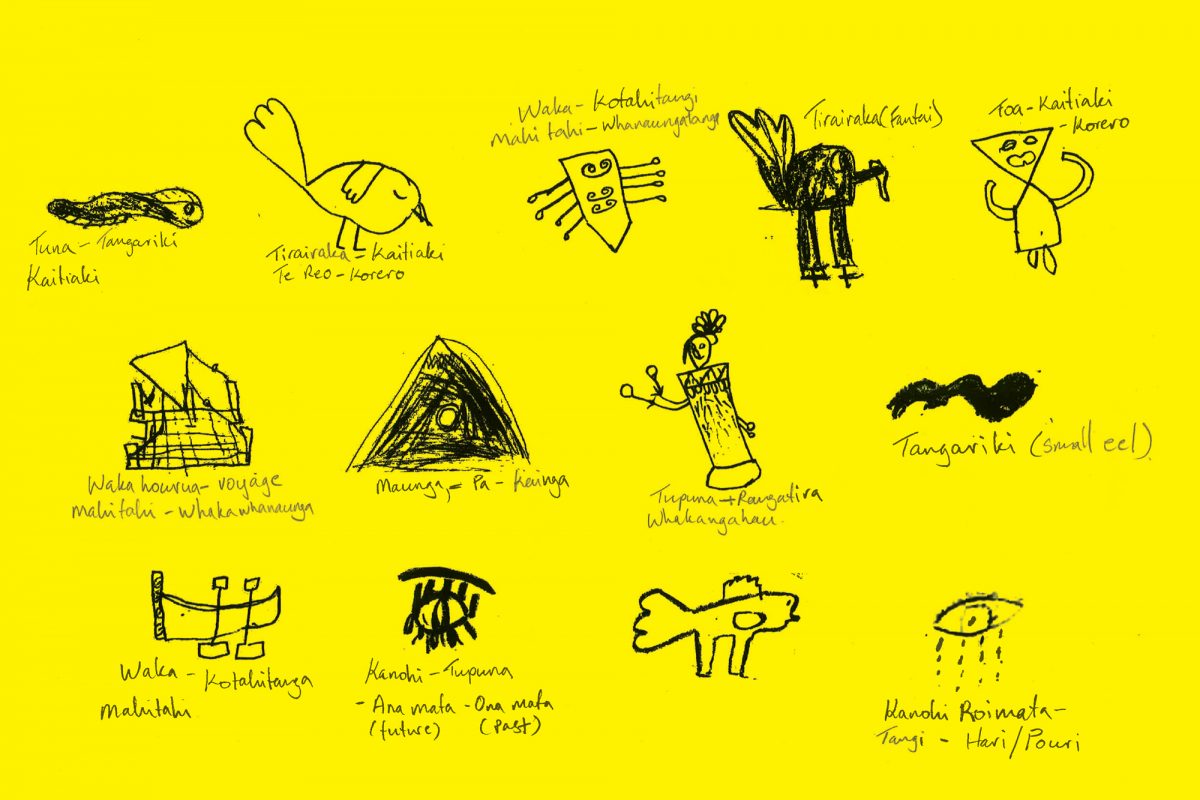

ĀKAU is supported by architects and urban and graphic designers from around Aotearoa, but finding designers locally can be a challenge. Through its ĀKAU Futures! program, ĀKAU works with local schools to inspire and support young people, some of whom who have started disengaging with their education. “Hopefully, through learning the design process they build confidence, learn more about themselves, and see that they are contributing to their community,” says Heremaia. The pathway for Māori into architecture and design is difficult, and Māori are hugely underrepresented within the profession. Through teaching design at a younger age, ĀKAU hopes to create a new generation of empowered Māori designers.

ĀKAU’s work extends far beyond the Western conceptions of the practice of architecture and design, taught in schools and universities, which in some cases creates distance between the built environment and the people who inhabit it. With every project, big or small, they weave together the needs and wants of their community with the act of making, Indigenising design by connecting to the land, bringing narratives passed down through thousands of years to the surface, and enabling mana (power) for the people of Kaikohe.

This piece is part of Assemble Papers 13 Mind the Gap, published at the beginning of February 2021. Find the print version of Mind the Gap at cafes across Melbourne, or order a copy from our webshop and pay only postage costs.