Gamifying urban design with Block by Block

The development of our public spaces often feels hidden behind complex planning processes, motivated by the visions of a few. Could a more participatory design method help us to re-imagine the present and future of public spaces together? To find out, writer Robert Snelling chatted with Celine d’Cruz, vice president of Block by Block, a growing global experiment in participatory urban design with over 100 projects around the world.

“Imagine at age eleven or twelve that your world is a large, open, dry expanse of land.” Celine d’Cruz is recounting her visit to a Kenyan refugee camp. “No one will ask you what you want from the space. Everyone is just trying to survive.” For many children, an opportunity to co-create a piece of their world provides a moment of respite, “to imagine a piece of green, a swing, or a place to hang out with friends makes a difference. It becomes a lifeline.”

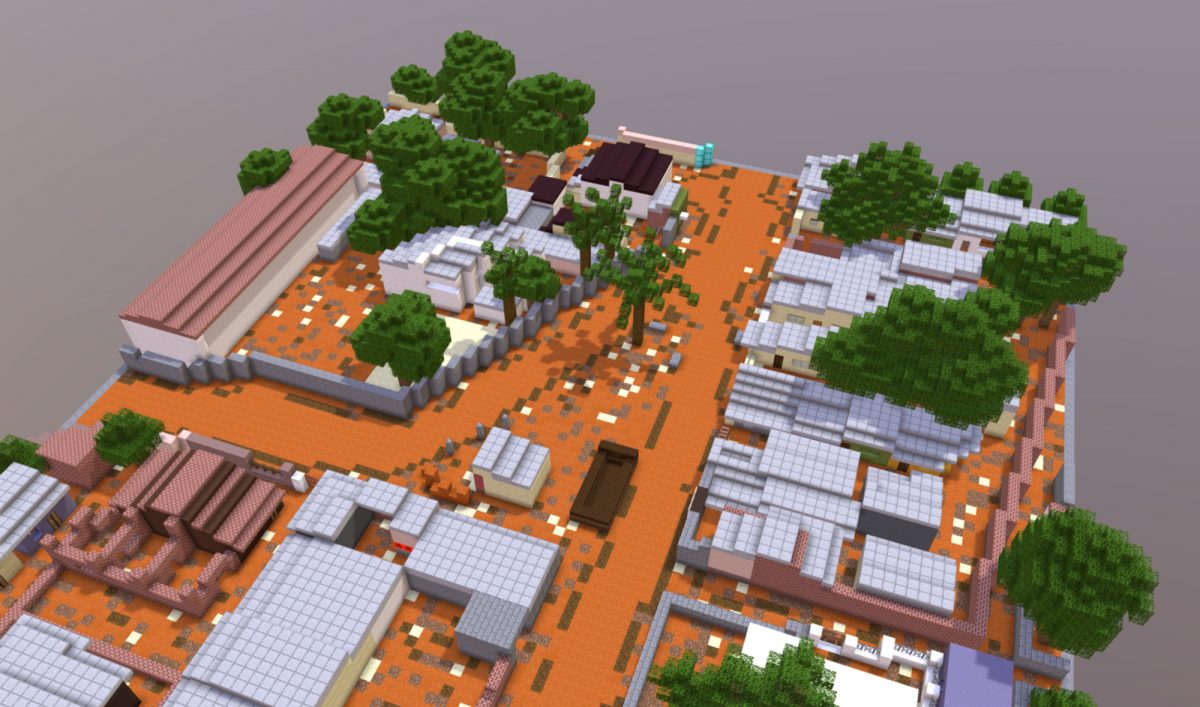

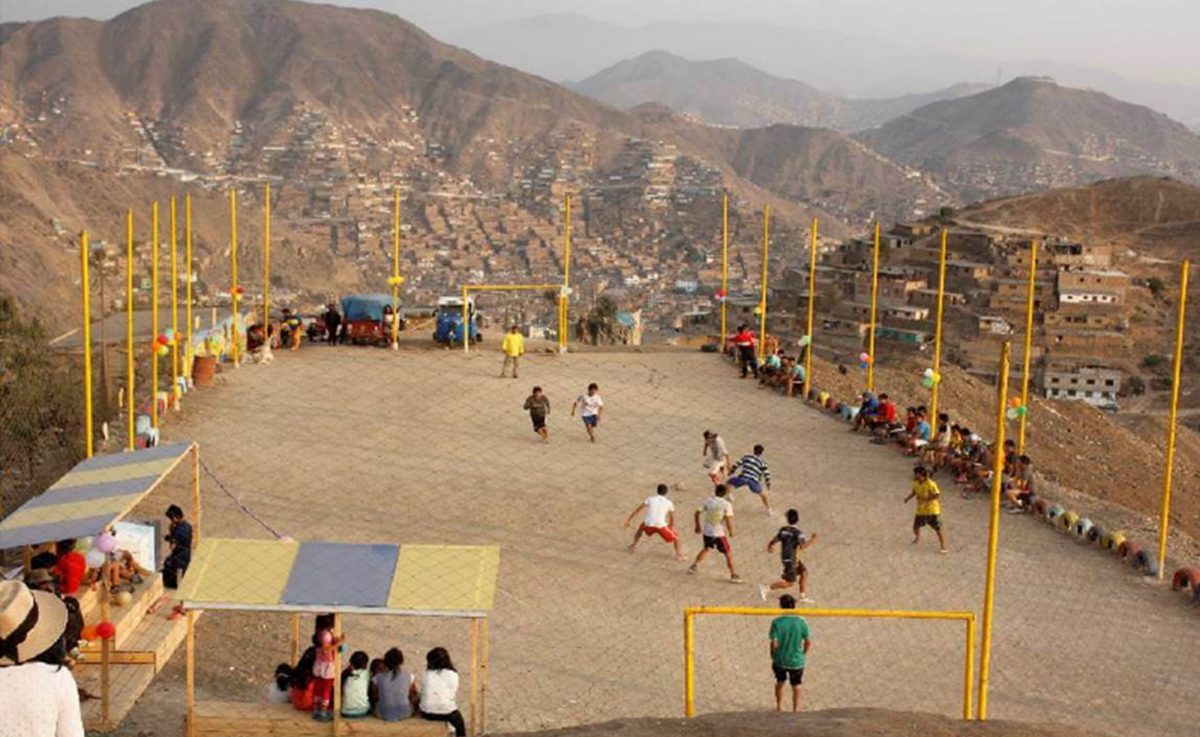

Celine is describing one of many projects by Block by Block. For nearly a decade, the foundation has been using Minecraft – a computer game with a block-like interface where players can build their own environments – as a medium for communities to co-transform neglected urban spaces. The projects are primarily spread across developing nations, including Asia, Africa, the Arab States and Latin America. In Peru, a small community movement has been slowly co-transforming the lanes and parks of Villa El Salvador in Lima. Ocupa tu Calle (‘Occupy your Street’) has transformed twenty-one neglected and under-used urban spaces into parklets and playgrounds, market places and cultural spaces. One intervention, Mama Lucinda Park, is named to honour the efforts of Lucinda Terrazas, now 80, who still continues to campaign for neighbourhood improvements.

“I started off as a non-believer in Minecraft,” explains Celine, currently based in Mumbai. “I thought, ‘you can’t just approach communities with this game that they may not have had exposure or access to’. I couldn’t understand how Minecraft could be translated as a tool for urban design.” With twenty-five years of experience within informal settlements, Celine is currently a Visiting Researcher with the Bangladesh-based International Centre for Climate Change and Development, focusing on locally-led climate change adaptation in developing economies. She is also a founding member of Slum Dwellers International, an organisation that has campaigned for an urban development agenda that considers the integral and often forgotten role of informal settlements in cities. Since its inception in 1996, Slum Dwellers International has helped build a network of organisations representing the urban poor in over thirty countries. With a career dedicated to helping households obtain secure housing and basic municipal services, Celine was invited to join the Block by Block board in 2016.

“It’s like the other side of the coin – you can’t have effective housing without also designing the open spaces in your city.”

Although Celine’s background is more rooted in housing than public space design, which is the focus of Block by Block, she emphasises the intrinsic intertwining of homes and public spaces: “It’s like the other side of the coin – you can’t have effective housing without also designing the open spaces in your city.” Within developing cities, informal communities can constitute up to 80% of a city’s population, bringing with them an expansive, complex and thriving informal economy. Many residents use their homes as a place of production, while public spaces become marketplaces. Dense informal settlements often lack the open public spaces needed for trade as well as recreation. Creating secure, well-designed spaces for informal workers is critical not only to their livelihoods, but to the city’s economy too. Using Minecraft as a design tool has led to the organisation’s success. The magnetism of Minecraft’s simple interface and the delight that comes with creating spaces captivates communities. As Celine explains, “During workshops, the kids are giggling and laughing while imagining their public space. They are excited but totally engaged in creating through play.”

Unlike architectural drawings or planning terminology, Minecraft’s simple visual appeal surpasses language barriers both linguistic and discipline-specific. Participatory urban development can also be a highly cultural-specific process, yet Block by Block’s linguistic-free nature has enabled repeated success. Since its founding in 2012, the organisation has grown substantially. Mojang (Minecraft’s parent company) formed a relationship with UN-Habitat, aiding Block by Block’s initial growth and establishment. Microsoft’s acquisition of Mojang in 2014 helped formalise Block by Block as a registered charity and diversify its fundraising sources. Today, Microsoft provides financial and technical support for the program, while UN-Habitat oversees and supports the implementation of projects.

Once a year, UN-Habitat and Block by Block call for proposals, receiving applications from municipalities, governments and NGOs. They look at how these proposals can address critical urban issues, such as improving gender equality or enhancing accessibility to urban spaces. Once a proposal is selected, UN-Habitat scans at the city level for what public spaces exist and identifies key project priorities, in consultation with communities. After the sites and project priorities are clarified, UN-Habitat facilitates the Minecraft session; in turn, young representatives from a local municipality or NGO are trained to run future public space workshops. The methodology helps establish a relationship between communities and local governments. Following the design workshop, communities prioritise the final designs with municipalities; the designs are documented by architects before the community co-builds the spaces. By working on public spaces instead of housing, it surmounts traditional roadblocks in urban development. Celine says, “Having a conversation on public space with local government is so much easier than saying ‘give us land for houses’.” The power arises from its low-key, non-controversial nature while the playful character of Minecraft presents itself as a non-threatening tool and reduces political tension. In Lima, the success of Ocupa tu Calle is creating momentum, with a greater push to include public space design in the city’s public policies and agendas.

Gamifying public space design captivates a younger generation, ensuring their current experiences and future visions for a site are expressed. Celine describes one workshop she visited in Hanoi in 2019, where young girls from a local school were asked to imagine their city. In that community, many girls stressed the discomfort they felt in urban spaces that were dark, narrow and lacking proper visibility. A subsequent co-design process could have involved printed maps and sticky notes, but Block by Block used virtual blocks in a digitally replicated neighbourhood to help participants communicate complex ideas of space. Through limiting the design parameters to a set of coloured digital cubes, participants focused on the spaces they were creating instead of fixating on the tool they were using. The girls co-created ideas such as additional lights and removing vandalism to create a safer, well-lit underpass. Every workshop also intends to meld different lived experiences and distil them into a new public place, bringing together many generations. While younger participants stack digital blocks to test ideas, the older generation brings their local knowledge, emphasising the importance of safe spaces to sit and rest.

Despite the challenges of the Covid-19 pandemic, the momentum of Block by Block is not waning, but revealing new opportunities for the organisation to evolve. Celine mentions, “After Covid-19, it will be very clear where communities need to strengthen their resilience, and how public space plays a very important role in rebuilding that resilience.” Further, travel restrictions have enabled UN-Habitat to conduct workshops online, enabling a greater reach than before.

For Celine, once the trust in Block by Block’s approach is built, there could be scope to work with groups not recognised by a city. For example, waste-pickers and street vendors in cities like Mumbai in India need public spaces to conduct their work, yet these groups are not formally acknowledged by local municipalities. She is curious to explore whether spaces designed for these groups can also work for the broader city. “We need to understand and then meet the public space needs of the informal city, as public space is also a livelihood for certain people.” There is much to explore in how to define public space in the context of urban poverty, how it can bridge the informal and formal city. “The whole point of these projects is to bring about change in urban environments, in a way that empowers the people who live there,” she says. “If successful, Block by Block could have a tremendous effect, having already impacted the lives of 1.72 million people. And at any scale, it would have created all of these beautiful projects in different cities.”