From resilience to sustainability in cultural institutions

The effects of the Covid-19 pandemic have exasperated underlying structural conditions and inequalities we face as a society. Here in Australia, an underfunded art world is struggling to stay afloat. What do contemporary arts organisations and institutions look like in a post-pandemic world, and how can their financial models become more sustainable? Artistic Director and CEO at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA) Max Delany, shares his vision for a more sustainable and equitable future for the art world.

Artist Andrea Büttner’s Beggar series from 2016, presented at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA) last year in the exhibition On Vulnerability and Doubt, explores a number of philosophical and ethical questions around poverty and shame, the increasingly divisive positioning of ‘us’ and ‘them’, and the denigration of the vulnerable, the outsider and the poor. Büttner’s prints also reflect on the relationship between art and economics, poverty and patronage; they are salutary images for our time – we might even think of Büttner’s prostrate figures as images of artists (and indeed arts organisations) before their patrons.

The context of the Covid-19 pandemic has radically redrawn the cultural and economic landscape, and has placed the arts and cultural sector in an especially precarious situation. But rather than being an anomaly – or some ‘unprecedented situation’, as we have heard so often – the pandemic has simply magnified the deep vulnerability of the arts sector in Australia.

One only has to look to recent cultural funding and policy scenarios to understand the strain and vulnerability that we face as a sector, such as the outcome of the Australia Council’s four-year funding process; the recent case of Sydney’s Carriageworks entering into voluntary administration; and the ineligibility of so many independent artists to qualify for the JobKeeper Payment, along with a seeming lack of interest or will by the federal government to consider targeted support (this eventually came on 25 June, albeit in a limited way, as part of a ‘creative economy support package’, but it doesn’t really address the plight of individual artists and arts workers). As an Australia Council media release dryly noted: “This is not business as usual for anyone, and arts organisations also will need to adapt in order to weather these unprecedented times.”

Social distancing is the opposite of how we normally prefer to work in the cultural sphere. The Covid-19 pandemic has been a test of our values, protocols and institutional practices, and has put many things into perspective.

The idea of adaptation brings us to the question of resilience: the capacity to withstand times of hardship and to recover, to bounce back into shape. It has indeed been inspiring to see the ways in which artists, arts workers and cultural organisations have risen to the challenge of a national health emergency, in ways that speak to their solidarity with other colleagues in the field, including those who are more vulnerable. It shows a commitment by the sector to the public good and to civic generosity.

However, the term ‘resilience’ inevitably suggests a body under stress and duress. Rather than focus on resilience and resourcefulness, we should question the systematic precariousness within the arts and look towards models of sustainability and capacity building. The arts and cultural sector should no longer be in a position of resilience in the face of hardship and stress; it should be set up for prosperity, whereby the contribution of artists and cultural organisations to our society is understood, valued and supported. Despite these uncertain times, we need to turn our minds to the future – its challenges and opportunities, and how we can plan for the cultivation of a strong and vibrant cultural and public sphere.

In the first two globalising decades of the 21st century, beyond the specifics of the Covid-19 pandemic, we have seen neoliberal economic policies, increasing economic precarity, threats to security from fundamentalism and popularist politics, and climate crisis. We have seen the increasing prevalence of market-led models for cultural institutions, which must increasingly rely on corporate sponsorship, private philanthropy and commercial revenues as government funding recedes. As the London’s Tate Modern director Frances Morris recently observed, museums in the wake of the pandemic are newly vulnerable, working in conditions of extreme instability; she also notes that, as cultural organisations move from survival to stability, “we have an incredible opportunity to shift the way we work”.

This question of how we might work better collectively was the specific focus of the exhibition Greater Together, curated by Annika Kristensen in 2017, and has occupied our thinking at ACCA in recent years. Our role is to be a platform for artists, to invest in our cultural communities, to be a centre for the exchange of ideas, and, ideally, to reflect and inspire positive change in people and communities. With projects such as Sovereignty (2016–17) and Unfinished Business: Perspectives on art and feminism (2018–19), we explored a shift away from authorial modes of curatorial practice towards more collective and collaborative curatorial methodologies, encouraging diverse voices and cultural perspectives, as well as reflexive, experimental working methods. Increasingly, we see our role not only as a centre for our own activities but equally as a platform for others, giving voice to artists, and working with colleagues and audiences as collaborators to create meaningful participation, cultural belonging and exchange.

In the period ahead, cultural institutions will need to argue for the value of public culture itself, and the public value of what we do. We will need to establish new strategic partnerships and modes of collaboration, while building new alliances with more diverse communities. It is increasingly important to open up our cultural institutions, and to consolidate ideals of inclusion, access and diversity in the face of increasing intolerance of difference. Our creative sector will be crucial to help rebuild and animate communities in the wake of the social and economic shocks caused by this pandemic, and we will need to support those among us who are most vulnerable and affected by the economic and social disruption; this will require structural change and investment. We will need to experiment in new forms of partnership and community alliances, and to rethink our exhibition and event models. In addition to being sites of inspiration and aesthetics, public art galleries and cultural organisations have a role in generating debate and discourse around the important contemporary social, cultural and political challenges of our time.

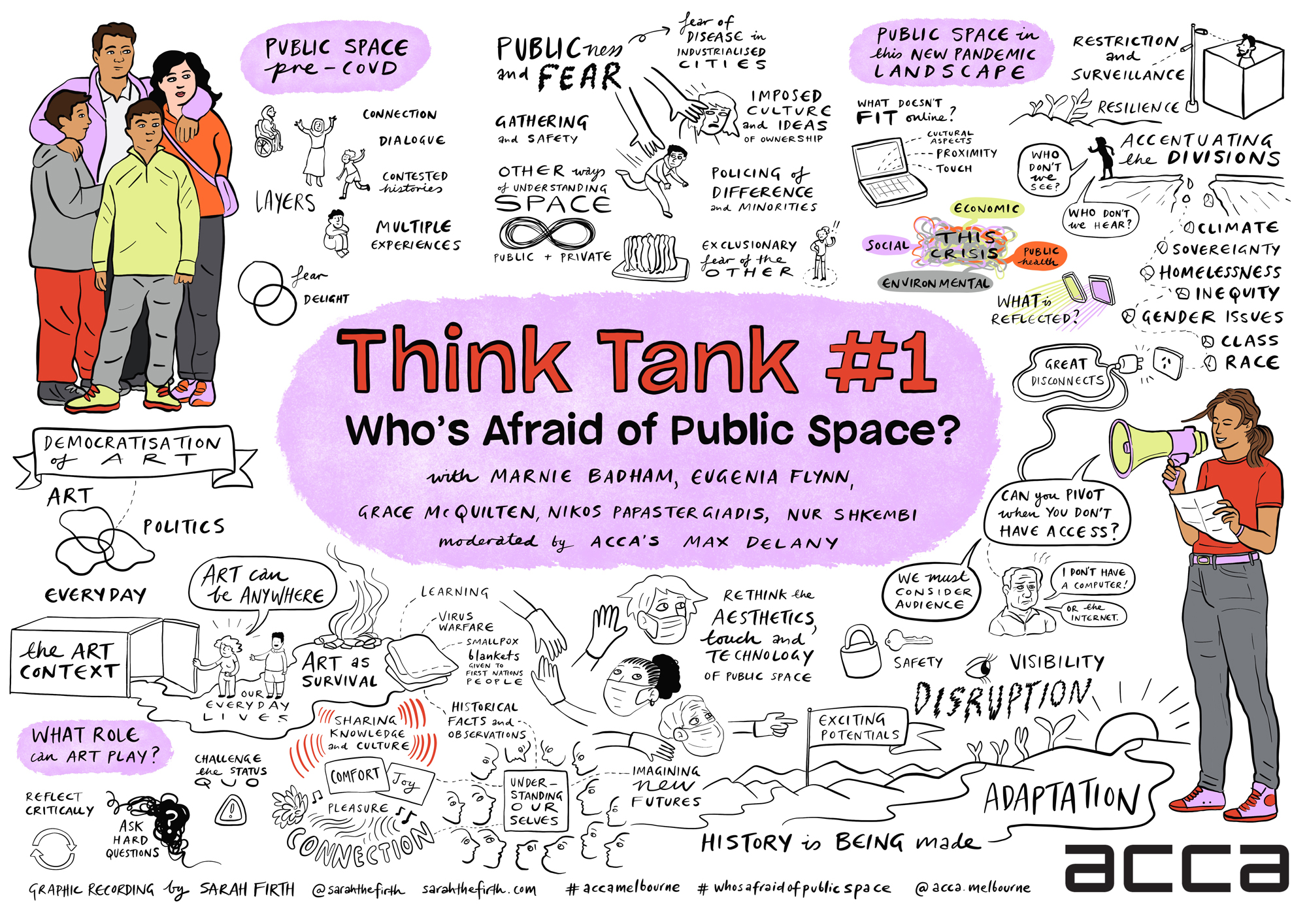

Alongside ideals of collaboration and solidarity sit principles of decentralisation, and democratic decision-making. How to truly realise collective cultural practices and experiences? This question is the challenge that we have set for ourselves with a new exhibition project, to be developed over a two-year period in the lead-up to ACCA’s summer season of 2021–2022. Who’s Afraid of Public Space? will explore the role of public culture, the contested nature of public space, and the character and composition of public life itself. Working with an assembly of artists, collaborators and partners, the project is organised according to a dispersed, distributed structure, developed with collaborating curators, partner organisations and community groups, to encourage a more diverse understanding of our increasingly complex public and cultural realm. A challenge for the exhibition, and for cultural institutions more generally, will be to engage and activate communities as part of a wider project of civic engagement.

Social distancing is the opposite of how we normally prefer to work in the cultural sphere. The Covid-19 pandemic has been a test of our values, protocols and institutional practices, and has put many things into perspective. As Frances Morris has suggested, “The silver lining of this crisis for museums [to which, I would add, for the cultural sector at large], may be a more rapid descent from the ‘temple on the hill’ model of the art museum, to a more egalitarian, more open-ended, and more participatory institution that can engage contemporary society in its full diversity.” I hope that it might also stimulate a move from ideals of resilience and resourcefulness, to a situation based on sustainability and structural change.

Thank you Max, for sharing your thoughts on the future of the art world here in Melbourne. This is an edited version of a presentation, delivered as part of a panel discussion, ‘Which Resilience, Why Resilience, Whose Resilience?’, Centre of Visual Art, University of Melbourne, convened by Vikki McInnes, via Zoom on 25 May 2020.