Questioning Cold War relationships at Ex-Embassy in Berlin

In August 2018, the former Australian embassy to East Germany in Berlin’s northeast suburb of Pankow hosted Ex-Embassy, an exhibition of six artworks and five texts, and an open research archive. Instigated and hosted by the artist Sonja Hornung, and researched and assembled with writer and artist Rachel O’Reilly as curatorial advisor, it included the works of Aboriginal and European artists, and a program of talks, tours, discussions and events – questioning the Cold War relations between Australia and East Germany, and their ongoing spatial legacies.

Sonja Hornung

In early 2017, an email circulated among Berlin artists calling for applications to sublet spaces in the former Australian embassy to the German Democratic Republic (GDR). I knew the building, located in the north-eastern reaches of Pankow. In a previous artistic project, I had looked at the extraterritoriality of the embassy form – an embassy is not legally part of the country where it is located, but instead is under the jurisdiction of the country it represents. I brought together a number of friends, and we joined around 25 other artists to establish a studio complex in the heritage-listed building under a temporary-use contract.

I moved to work in the former embassy with the explicit intention of digging deeper into the site. As an artist-occupant of the studios, I was well aware we were placeholders, or even value enhancers, for the building’s anticipated future as luxury flats. So, parallel to Ex-Embassy, together with the other studio artists, I was heavily involved in attempting to establish an alternative, collective ownership structure for the site in order to extract it from the speculation cycle.

As my research for Ex-Embassy expanded erratically in several directions at once, it quickly became clear that the story of the place could not be reduced to the past, or to one location. I began thinking about an exhibition format in which the building could be considered as a non-neutral frame, accountable to the inquiries of artists and researchers external to our studio community.

Rachel O’Reilly

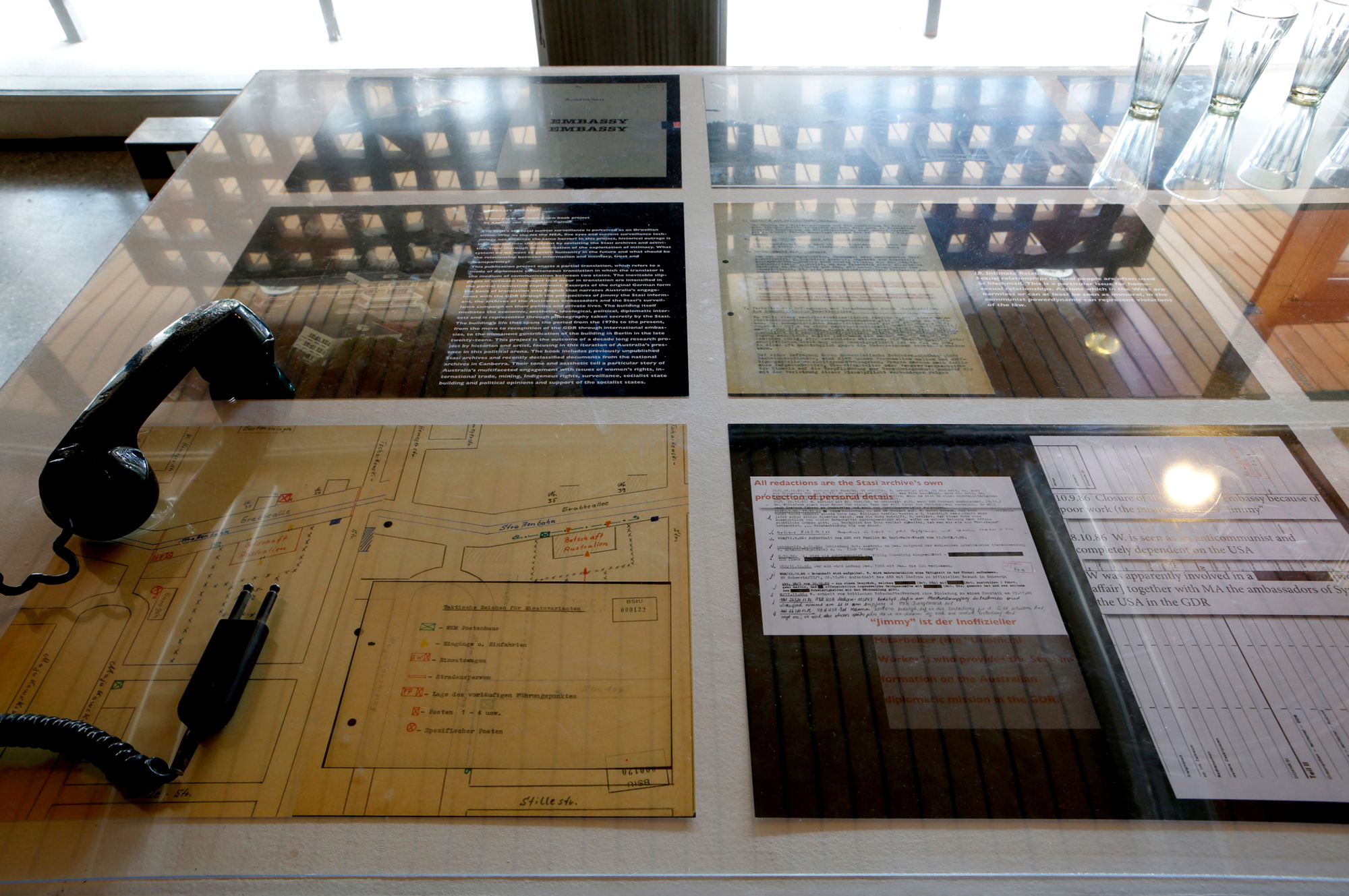

When Sonja first approached me with the project, I was less interested in the architectural site than in the inherent incompleteness of the archive – which included building plans, diplomatic communiques and research texts – and the revisionism that comes with this. There is a lot of nostalgia around the Cold War, not only because of the pressure socialism asserted upon democratic ideals in the post-WWII West. There have been key exhibitions re-reading this period as one of soft power trafficking between normative spaces of politics and internationalist art, such as Parapolitics: Cultural Freedom and the Cold War (Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, 2018). Less attention has been paid to the role of colonial law in defining Cold War paradigms of autonomy, peace and war set up by liberal ‘international(/ist) relations’.

I was conscious of the fact that Germany in the 1990s also played host to game-changing Aboriginal-controlled exhibitions such as Aratjara (Kunstsammlung Nordhrein-Westfalen, 1993), which followed in the wake of Magiciens de la Terre (Centre Georges Pompidou, 1989), and has been a destination for transnational diplomacy before, after, and on both sides of the Wall. Such practices build on a truncated legacy of politics and art that refused post-war ‘business as usual’, and that did not always tactically coincide with state projects. Australia did not participate in the Non-Aligned Movement, while Indigenous land rights and decolonising movements in South East Asia challenged the imperial legacies of the liberal international governance and legal system.

In Pankow, we considered specific stories which offer an insight into the under-documented leveraging that took place during the Cold War: Faith Bandler and Ray Peckham, for example, both instrumental in the campaign for the Aboriginal vote, travelled to East Berlin in 1951 under surveillance by the recently formed ASIO, performing as part of the World Youth Festival for Peace and talking to factory workers on Aboriginal equality and citizen rights. Members of the Aboriginal rock band No Fixed Address were effusively received in the 1980s on two occasions by East Berliners, including in Berlin’s famed Volksbühne, as ‘proof’ of the cruelties of colonial capitalism. Our invitations to host artists Megan Cope (Quandamooka, also of the proppaNOW collective) and Archie Moore (Kamilaroi) came through interest in connecting renowned and current-generation Aboriginal artists into local conversations on the inheritance of post-war and post-Wall artistic movements.

SH

In December 1972, following Gough Whitlam’s election, relations established between the GDR and Australia were among the first to be negotiated between the socialist GDR and a Western capitalist state. So East and West Germany’s acknowledgement of one another in 1972 represented a clear turning-point in the Cold War, making it far less complicated for Non-Aligned and Western states such as Australia to set up formal diplomatic ties to the GDR.

Because of this, there was a sudden demand for new embassies and diplomatic residencies in the GDR, which were rapidly rolled out, largely in Berlin’s northeastern suburb of Pankow. Four variable models became the basis for 135 uniform diplomatic buildings – the largest of which hosted the Australian embassy. The designs are almost entirely bereft of national signifiers. The technical legacy of this ‘experiment’ lies in the art of prefabrication, which the GDR first implemented in mass housing projects: a one-size-fits-all approach specific to socialist modernist architecture, manifest in a grid-like formal efficiency.

…we must ask: by whom, and for whom, is property structured? It is a matter of some urgency that these structures of belonging are resilient and malleable enough to accommodate the ‘simultaneity of stories thus far’.

SH/ROR

The exhibition itself took as its starting-point the building’s standardised (but by no means ‘neutral’) form. Drawing on British geographer Doreen Massey’s approach to space understood as the “simultaneity of stories thus far”, including all that does not formally or legally fit into the modernist grid, we wanted this form to immediately be traversed by further narratives.

For the exhibition duration, we kept the building’s more monumental main entrance locked shut. Signage directed visitors to instead wander through the overgrown garden, encountering two outdoor works: Archie Moore’s Image (2018) – a physical barrier projecting an illusion of freedom via a fake garden space – and German artist Sonya Schönberger’s Clean Square (2018), a reflection on the forceful re-construction and containment of specific (urban) spaces. Video documentation of Sumugan Sivanesan, Carl Gerber and Simone van Dijken’s onsite ‘tennis-performance’, Ex-Pat Cash (2018), as well as a photocopied archive of research materials (which continued to be expanded after the exhibition opened), and the printed commissioned texts, were available to visitors before they finally entered the building via a back balcony door.

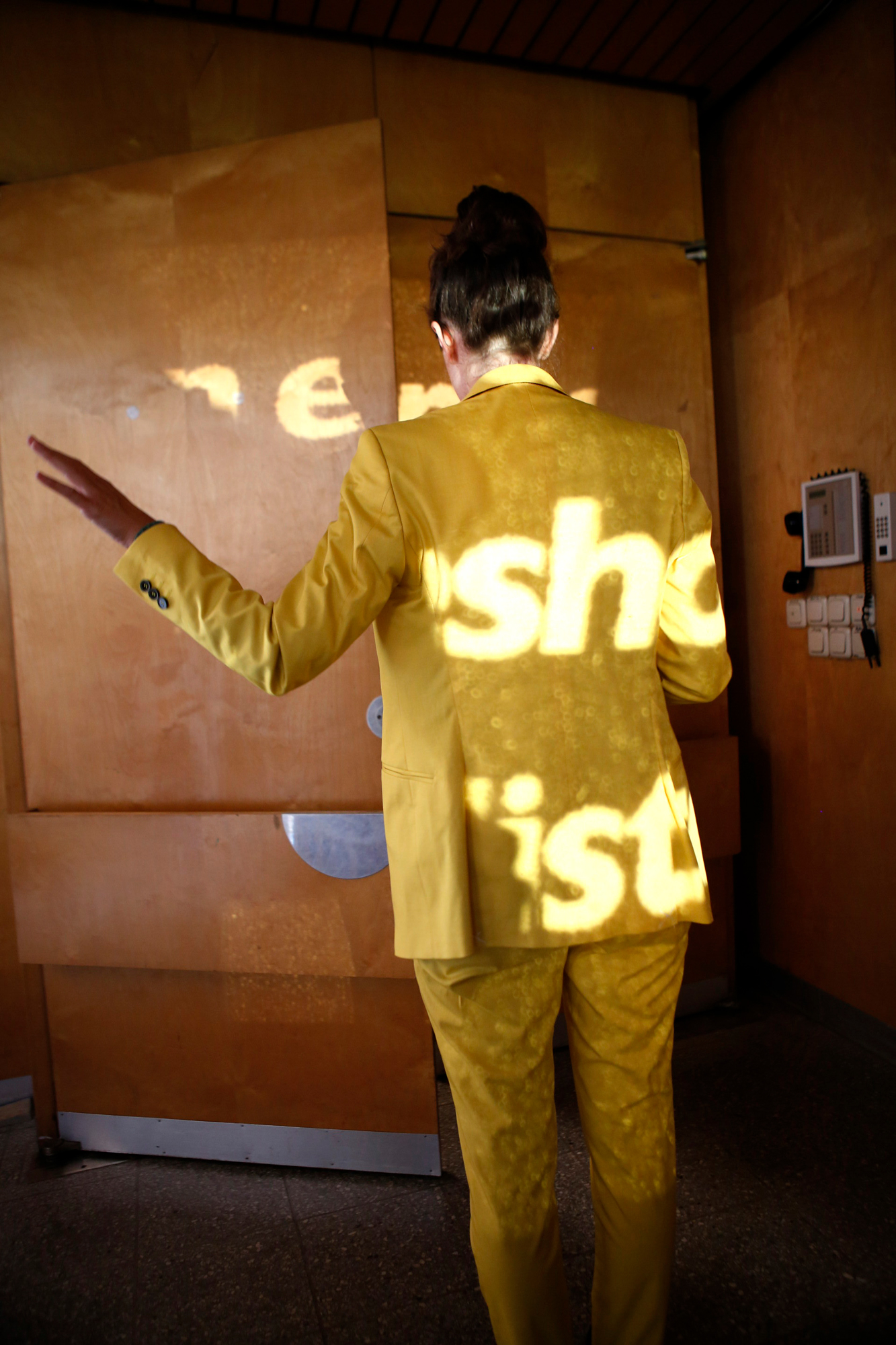

The ostentatious, wood-panelled conference room was dominated by two works destaging that central meeting space: Archie Moore’s Text (2018) – which presents parliamentary records dating back to 1901, emphasising Australian politicians’ historical use of the phrase ‘swamped by…’ (‘…Asians’; ‘…the Aboriginal vote’; ‘…Communists’ etc.) – and Megan Cope’s video work The Blaktism (2014), in which a Quandamooka woman undertakes a ceremonial anointing in order to have her status recognised in a ‘white phantasy’ (as Romaine Moreton has called it) upheld by ever-present cultural authorities in the Australian landscape. The last work in this reversed tour, Khadija von Zinnenburg Carroll’s Embassy Embassy (2009–2018), brought together nearly a decade of artistic research on the former Australian embassy and its architectural ‘twin’, the Iraqi embassy, including a slide projection onto the inside of the closed entrance doors.

ROR

The exhibition attracted visitors from outside the fields of art and architecture. Many visitors (whether local or international) did come with the simple motivation of viewing a building which had long been restricted to access, but then encountered content that expanded their expectations, and stayed for a longer conversation about unfamiliar parts of the archive. It was important for us to be physically present during opening hours, accountable and available for questions and comments.

Contributing writer Sarah Keenan drew links between racialised property law in the settler colonies and the question of access and ownership globally, in financialising housing markets. Here, there is an ongoing connection between property and belonging: citizenship gives you property rights, while various forms of collective property ownership were extinguished in settler colonies with the invasion of Indigenous lands. The reward for participation in the colonial project was not just white citizenship but private property protections – the ability to become upwardly mobile through exclusive use and exploitation. Keenan’s work opens towards an emphasis on belonging as a malleable process negotiated via use, membership and social movement, and not just via the modernist ownership framework (whether private or collective).

Another contributor, cultural studies theorist Ben Gook, argues that post-1990, Cold War ideological conflicts were reduced to “the politics of real estate”. During the ‘transition’ to capitalism, Treuhand – which was the major federal trust agency set up to manage the GDR’s former assets – privatised not only land and housing, but also firms and institutions, resulting in massive infrastructural and social upheaval. Gook argues that despite its clear failures, privatisation here formed the testing ground for processes more recently imposed by the German state elsewhere via the European Central Bank – in order to claim new markets within European Union borders after the 2008–2009 crisis, most famously in Greece.

SH

In cities like Berlin or indeed Melbourne, the more democratic local governments and communities are scrambling to reclaim a fraction of previously privatised assets – either via community land trusts, public–private partnerships or straight-out remunicipalisation – on the back of widespread popular resistance. Yet calls for communal ownership structures set to counter financialisation should be attentive to the fuller play of continuities, imbalances, exclusions and violences.

And what of the embassy? Post-1990, the site became the temporary parking place for the GDR’s Deutsche Handelsbank, which originally handled the state’s foreign dealings and assets. The bank amalgamated into the Spanish conglomerate Santander, while the embassy itself continued to be held by Treuhand, then the Federal Institute for Real Estate, before finally being put up for sale in 2010. Over the next decade, the building changed hands three times and increased in price more than tenfold. At this price, the collective attempt to secure collective ownership of the site for permanent artistic use fell through – as did its planned transformation into luxury apartments. Both ventures proved to be too risky, an illustration of financialisation’s failure: here, even luxury apartments were no longer profitable. The Berlin Senate considered, and then rejected, a plan to recommunalise the site. Then surprisingly, in August 2019, the German Humanists’ Association acquired the embassy. It plans to develop a private, socially oriented school there, if the building’s substance – which urgently needs renovation – can be salvaged.

SH/ROR

Thinking with Sarah Keenan, we must ask: by whom, and for whom, is property structured? It is a matter of some urgency that these structures of belonging are resilient and malleable enough to accommodate the ‘simultaneity of stories thus far’.

Thank you Rachel and Sonja for taking the time to speak to us about Ex-Embassy. This article also appears in Assemble Papers print issue #12.