Compiling new metonyms of place in Bosnia & Herzegovina

Between September 2018 and July 2019, Ennis Cehic and Shantanu Starick travelled extensively through Bosnia & Herzegovina to compile imagery, texts and ideas for their literary photography book, New Metonyms. For many people Bosnia & Herzegovina still conjures up images of war, thus their mission was simple. They set out to demonstrate that Bosnia is not just a country with a lingering memory of the 90s conflict, but a place with bountiful nature and history.

As a diasporic person, who was exiled from Bosnia in 1992, this was a very personal journey for me. Bosnia is full of stories and poetry, and having Shantanu’s outsider eye enabled me to capture the country in a very unique way. It was a decisive journey for me as a writer—I was tackling the narrative of my past to better grasp the essence of my displacement. The following places and landmarks are potential new metonyms we uncovered with excerpts from the book’s essay and poems.

Vrelo Bosne (Spring of the Bosna river)

For Bosnians, there’s an obsessive association with Vrelo Bosne.

Reminiscent of a pilgrim’s journey, Bosnians descend upon this spring of the river Bosna with anticipation. Here, the young and the old stroll meditatively, before they continue through the park to the grand promenade that takes them past the famous, stately villas of Ilidža. In summer and spring, when they see the water ripple and shimmer, a kind of collective synergy occurs—they begin a ritual I have seen many times. They kneel down and dip their hands into the flowing water. First, they splash it around their hands to feel the iciness. Then they rub the cold water over their necks, and their faces.

The act seems righteous, almost necessary. The river Bosna is the namesake of the country, and thus, Bosnia’s purest metonym—utterly absent of war.

Lukomir

Just southwest of Sarajevo, high up, at an altitude of 1,495m, you find a small, humble village called Lukomir. All around it are green pastures, old stone fences; and in the distant horizons, lonesome shepherds strolling with flocks of sheep. As you ascend to its small cluster of stone-and-wood houses with roofs made of rusted metal sheets, you feel like you’re entering the clouds. Time seems to stagnate here; it feels like you’ve entered a village from centuries ago. Villagers still wear traditional hand-knitted cardigans, dimije and the occasional fez. What’s remarkable about Lukomir, which means “harbour of peace” is that it’s the most remote village in Bosnia. But most significantly, it is untouched by war. It’s one of only two villages in these highlands that survived the onslaught of the Serbian forces in the 90s that razed through.

Ada on the Una

The word una means one in Latin. There are no direct citations, but for centuries it’s been told locally that the river Una got its name from the Romans. They allegedly found its beauty so mesmerising, they named it the one. I’ve always wondered what the Illyrians—the earliest known inhabitants of Bosnia and the most ancient race in south-eastern Europe called it. Did they also see it as the one? Or were the Romans, who collapsed the Illyrian kingdom around 9 AD the only ones to give it a name it rightfully deserves.

Monument to the Revolution, Mrakovica (Kozara National Park)

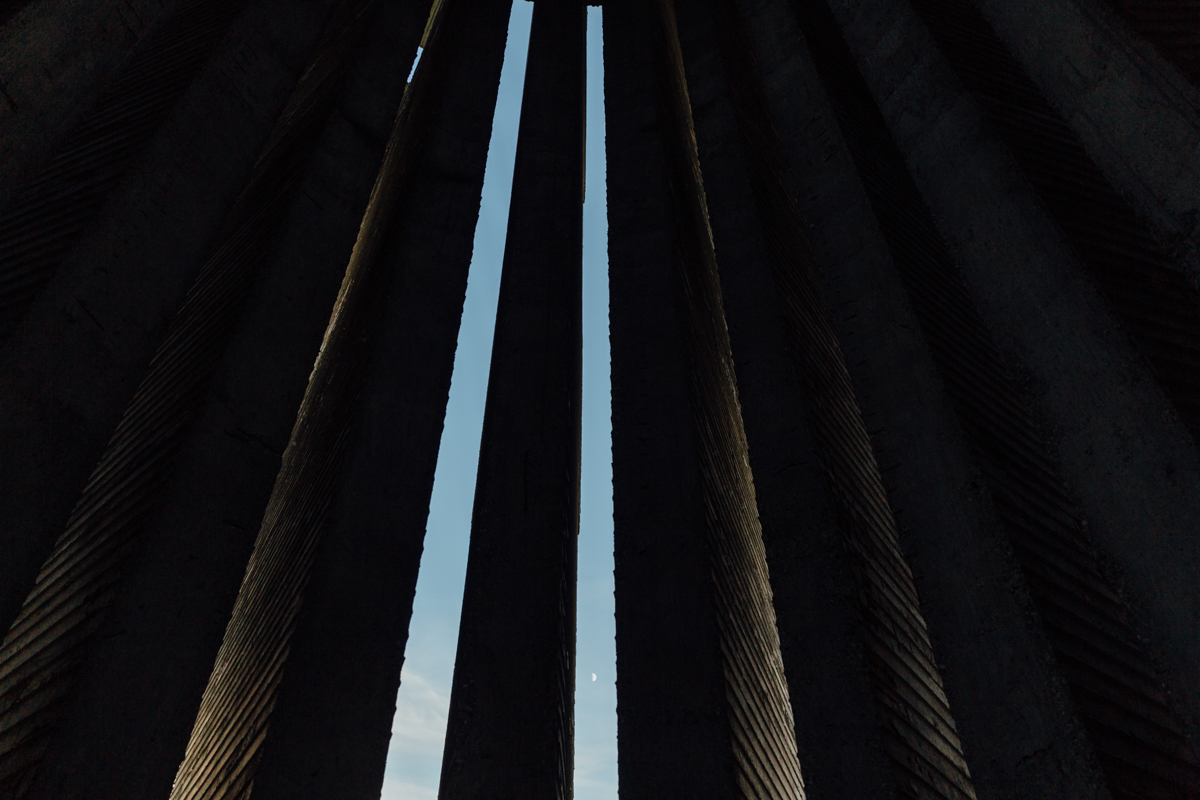

Over the last decade, since Belgian photographer Jan Kempenaers brought the abandoned monuments of former Yugoslavia to the attention of the world, Spomeniks (as they are called) have acquired incredible interest and appreciation, albeit without much of the crucial historical and ideological context that forged them. While they are derived from war, it is precisely this international interest that has extended their meanings. Their original intentions, commemorative ideology and history, weren’t required to develop new perceived images of Bosnia and the former Yugoslavia. They have become metonymic, representing a bygone era.

Two in particular mark the land of Bosnia: The Battle of Susjetska Memorial Monument in Tjentište and the Monument to the Revolution in Mrakovica (Kozara National Park). Their abstract, unique and sculptural designs have become a monument to Brutalist art, sculpture and architecture, rather than memorials of war, trauma and suffering. Now, the Spomeniks that exist in every single former Yugoslav country are viewed first and foremost as artistic statements and architectural pieces; only secondly, through their social context.

In-Between

We drive past an unceasing state of abandonment. A great quietness roams. People have left. Their houses are empty. Do their walls weep? Do their windows still seek the sun? This land isn’t forsaken. Its future is merely taking a break.

Thank you Ennis and Shantanu, for the opportunity to publish this story. The book New Metonyms: Bosnia & Herzegovina was intended to launch with a talk at The Wheeler Center in Melbourne in April, but was cancelled due to Covid-19. We hope you enjoy this little insight into the book, it is available to purchase through newmetonyms.com with worldwide shipping. 1st edition (500 copies), 2020.