Discovering 500 years of social housing at Munich’s ‘Fuggerei’

Adequate and affordable housing is crucial to human dignity and a sense of belonging. The Fuggerei, the oldest private social housing complex in Europe, aims to provide homes to vulnerable people in the city of Augsburg, Germany. Katharina Prugger and Henry Trumble, investigate the Fuggerei today, as it continues to operate on the same model as it did 500 years ago.

On a sunny Tuesday morning in autumnal Augsburg, Frau Thoma is overseeing the arrangement of a breakfast spread in the communal spaces of the Fuggerei. The hospitality veteran is in her element as she and the fellow volunteers await the rush of Fuggerei residents for the weekly social breakfast.

Frau Thoma’s home for the past eight years is located on 15,000 square metres in the historic inner city of Augsburg (in Bavaria), one of Germany’s oldest cities. The Fuggerei was founded in 1521 by Jakob Fugger, an important German merchant and banker, as a housing complex for citizens of Augsburg in need and has been in continuous use since then. The founding father left a brief, but very precise decree defining who could become a resident of the Fuggerei, which is being followed until today; residents have to be citizens of Augsburg, be respectable, be of Catholic faith and in need.

The weekly breakfast is one of a number of free social activities on offer for the current 150 Fuggerei residents. Volunteering is Frau Thoma’s opportunity to give back to the community she feels so fortunate to be a part of. With her pension from a forty-year career in hospitality, she could no longer afford the inner city life she had been accustomed to before retirement. As she was facing a move out of the city, worried about becoming isolated in a new area with lacking infrastructure, Frau Thoma decided to apply for housing at the Fuggerei.

The first step in the admission process is a phone call to the social workers on staff at the Fuggerei, who confirm that the core conditions stipulated by the founder are being met by the prospective resident. These are also checked against records at the registry office, church administration and the social services department. The waiting time for an apartment ranges from six months to seven years, depending on the person’s requirements. The ground-floor apartments are the most sought after: they each have a little garden, but also, importantly, they are more accessible than the first-floor residencies that require climbing up a steep staircase. The majority of the Fuggerei residents are elderly and female, reflecting the widespread problem of poverty amongst older single women.

Frau Thoma waited for two years until she could move into the Fuggerei. She values its tight-knit community and central location and acknowledges that the financial benefit enables her to have the same standard of living as before her retirement. Famously, the Fuggerei residents still pay the same annual rent that was set by Jakob Fugger 500 years ago: one Rhenish guilder – then about a week’s wages for a craftsman, today the equivalent of around 88 euro cents. In addition, residents are required to say three prayers every day – one Our Father, one Hail Mary and the Apostles’ Creed – for the Fugger family.

Ms Thoma regards the financial freedom the Fuggerei gives her as a luxury, enabling her to have a dignified life. As the homes come unfurnished, each resident can put their own stamp on them and Ms Thoma’s apartment radiates her welcoming and lively personality. She likes to interact with the many tourists and local visitors that come to the Fuggerei each day, and often has to correct the common misconception that the residents there live like in the Middle Ages, without modern sanitation or heating.

After the other Fuggerei residents leave the communal room, the volunteers sit down for their own breakfast. Joining the lively conversation is Doris Herzog, one of the two Fuggerei social workers. As the first point of contact for most prospective residents, she receives enquiries from all over the world. In recent years the requests have doubled, and the waiting list is longer than ever. Augsburg has been growing steadily, and – similarly to Geelong in Victoria – now also serves as a commuter city for workers in Munich. These changes in the city are reflected in rising rents and a lack of affordable housing. As most of the residents have spent the majority of their lives in Augsburg, they agree that even a few decades ago the Fuggerei did not have the reputation it has today, and they would not have considered applying for housing there. It was regarded as a ‘last port of call’ for poor old people, with a low standard of living. Today there are families and younger people living at the Fuggerei again and the foundation is valued and respected within the wider community of Augsburg. While the 500-year-old stipulation regarding the Catholic faith might seem outdated and not reflect Germany’s contemporary society, the Fuggerei staff argues that the social housing relieves communal welfare organisations financially, so they can spend more money on other members of the community.

Frau März, who also volunteers her time for the weekly social breakfast, certainly never pictured herself living at the Fuggerei, and always thought residents have to have been born in Augsburg to be eligible. She came to Augsburg from her native Hungary over twenty years ago, and recalls visiting the Fuggerei as a tourist with her family. After a divorce and having to leave the generous family home, the Fuggerei became her safe haven.

When Jakob Fugger founded the social housing complex, his intention was to give struggling tradespeople and labourers the opportunity to recover from hardship and find their own feet again. This concept of ‘Hilfe zur Selbsthilfe’ (‘ helping people to help themselves’) is still central to the foundation. As Doris Herzog puts it, their mission is to offer the residents an environment to find peace and happiness without the pressures from the outside world.

Surrounded by walls and shielded from the bustling city traffic, the Fuggerei functions like a city within the city, with Count Wolf-Dietrich von Hundt as its mayor. While his official title is that of administrator, he has not only managed all foundation business together with the Fugger Family Council for over twenty years but also lives at the Fuggerei with his own family and knows each of the residents. Sitting among historical art and furniture in one of the stately meeting rooms of the administration building, he speaks passionately about the founder and his legacy. Jakob Fugger is today considered one of the wealthiest people in the history of capitalism. Count Wolf-Dietrich von Hundt refers to him as one of the modern era’s first global players. He vividly recounts the wide reach of Fugger’s influence, from mining quicksilver in Spain – he doesn’t shy away from acknowledging the problematic working conditions there – to financing rulers of the Holy Roman Empire, and loaning money to the Vatican to build the new St. Peter’s Basilica and the Sistine Chapel.

A small replica of a portrait of Jakob Fugger painted in 1518 by Albrecht Dürer, the most significant artist of the German Renaissance, hangs in each of the 140 apartments of the Fuggerei.

Each residence has its own doorway, an almost luxurious level of privacy at the time when the first houses were built, between 1516 and 1523. Most of the entrances have a unique bell pull – it is said that they were individually designed so that the residents could find the right entrance when coming home late at night. The original architect of the complex, master builder Thomas Krebs, used a high standard of construction, but was also concerned to make the buildings aesthetically pleasing, for example adorning the sides of the buildings with stepped gables in the Gothic style. The original 52 houses, built along the first six lanes of the Fuggerei complex, were assigned Gothic house numbers and are considered the first numbered buildings in the city of Augsburg. Today, only some of the numbers are still intact.

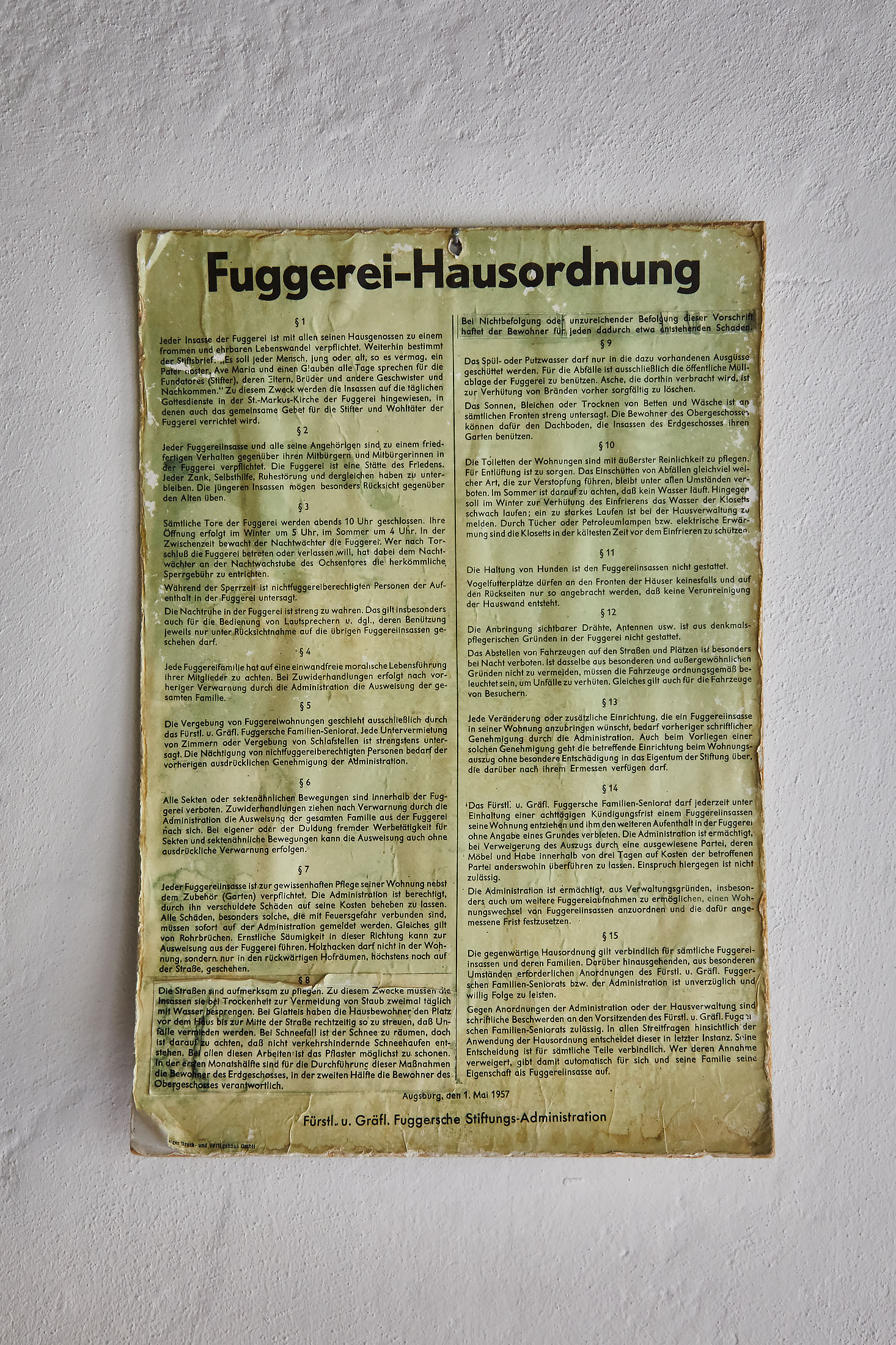

The Fuggerei is now one of Augsburg’s top tourist attractions; on this autumn day, the two museums that are part of the complex are swarming with school groups. The Fuggerei’s own church, St. Markus, is open to visitors as well. It was constructed in 1580, after the Catholic churches in the neighbourhood became Protestant during the Reformation. For the less spiritually inclined, there is also a beer garden and store to peruse. In the evening, though, the Fuggerei’s lanes and public spaces quieten down. The gates are locked between 10pm and 5am every night. Residents that come home late pay 50 cents as a tip to the nightguard, a fellow resident and volunteer (one euro if it is after midnight).

The buildings have witnessed a lot of turmoil over the centuries. During the Second World War, almost 70% of the Fuggerei was destroyed. The Fugger family decided to begin rebuilding the complex true to the original design almost immediately. The reconstruction was financed through sales of wood from the foundation’s forests, which historically and still today make up the main source of income for the Fuggerei. In 2006 the foundation started charging an entry fee to visitors, adding a second income stream that seems like an important foresight, considering the ever more extreme weather and dying forests that come with it.

Adequate housing is crucial to human dignity and, in a time when too many cities are faced with rising homelessness caused by a lack of affordable accommodation, and inaction by their governments, Fugger’s philanthropic legacy is more relevant than ever today.

Thank you Katharina and Henry, for shedding light on one of the oldest social housing initiatives in Europe. We also extend a warm thank you to the Fugger Family Council, Count Wolf-Dietrich von Hund, Astrid Gabler, and Frau Thoma, Doris Herzog, Frau März, and the Fuggerei community for letting us into their homes.