Envisioning a Corbusian Commune in Firminy

Among his last-conceived projects, Le Corbusier finally realised his vision for a new urban fabric in France. An old mining quarry became a platform for a modernist utopia of communal living. Writer Linsey Rendell visited the heritage-listed commune.

It’s Saturday morning and spirits are high in the usually sleepy town of Firminy in France’s Rhône-Alpes region. There’s a line out the door of the boucherie and a carefree hum to the streets circling the twice-weekly farmers’ market. As I weave through town, I notice the old gents sipping coffee out the front of the tabac. A few have already started on beer. Brightly hued stripes soon appear underfoot guiding my attention towards ‘the site’. I wonder which building will present itself first. Rounding a bend, my curiosity is cut short by a looming alien figure: Le Corbusier’s striking Église de Saint-Pierre.

The Swiss-French architect Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris needs little introduction. A prolific architect, urban planner, writer and Cubist-Purist painter, Le Corbusier ruffled feathers throughout his distinguished career, executing radical and often polarising ideas regarding architecture and housing, which went on to inform decades of urban design globally. A pioneer of modernist architecture, and one of the most influential architects of the 20th century, he worked intensely on his theories and built forms—before, during and after two world wars—perpetually iterating and publishing his resulting manifestos.

Among the housing shortage, growing population and economic depression following the first world war, he drew his attention to designing a new way of living, focusing on both housing and the city as a whole. He presented his theories in Ville Contemporaine de Trois Millions d’Habitants in 1922, before adapting his philosophies in La Ville Radieuse in 1930. “The analysis leads to new dimensions, new scales and synthesis to an urban organism so different from what exists that the mind can hardly imagine it,” he wrote. It’s his resulting utopia, still preserved and functioning, that’s drawn me to central France.

Le Corbusier sought to improve living conditions for apartment dwellers through the social and structural ideologies of his craft. “Modern life demands, and is waiting for, a new kind of plan, both for the house and the city,” he wrote. His response was the ‘vertical city’, or Unité d’Habitation. By building vertically, living could be done ‘in the sky’, dedicating more land to green space and cultural facilities at ground level.

In La Ville Radieuse, Corbusier abandoned his previous class-based communal living designs, adopting a more democratic approach with housing dimensions dependent on family size rather than economic status. “If the city were to become a human city, it would be a city without classes,” he proclaimed. A standardised 14 square metres would be awarded per person, with various floor plans spanning from ‘bachelor’ studios to multi-bedroom apartments for extended families.

Using what was at hand and what was affordable, he turned to béton-brut (rough-cast concrete) to bring form to his first large-scale residential block. “The materials of city planning are: sky, space, trees, steel and cement; in that order and that hierarchy,” he wrote. Corbusier applied his enduring manifesto, Five Points of a Modern Architecture, in which the pilotis (stilts or columns) not only created open, usable spaces at ground level and eliminated damp corners of a building, but also provided structure so that that the interior walls and facade design were liberated from load-bearing functionality. This allowed for ribbon windows to provide even daylight throughout the apartment. A garden on the rooftop would give back the land the building takes up.

While his Ville Contemporaine originally encouraged skyscrapers housing 600,000 inhabitants in a vertical urban dwelling, the actualised Unité d’Habitation was a 20-storey mixed-use residential block—which still came as a shock to French critics, who were accustomed to no more than seven or eight storeys at the time. These stacked ‘streets’ drew inspiration from both the Narkomfin building in Moscow, a social housing project by Moisei Ginzburg built in 1929; and luxury ocean liners, where thousands of passengers sleep, eat and live in close proximity.

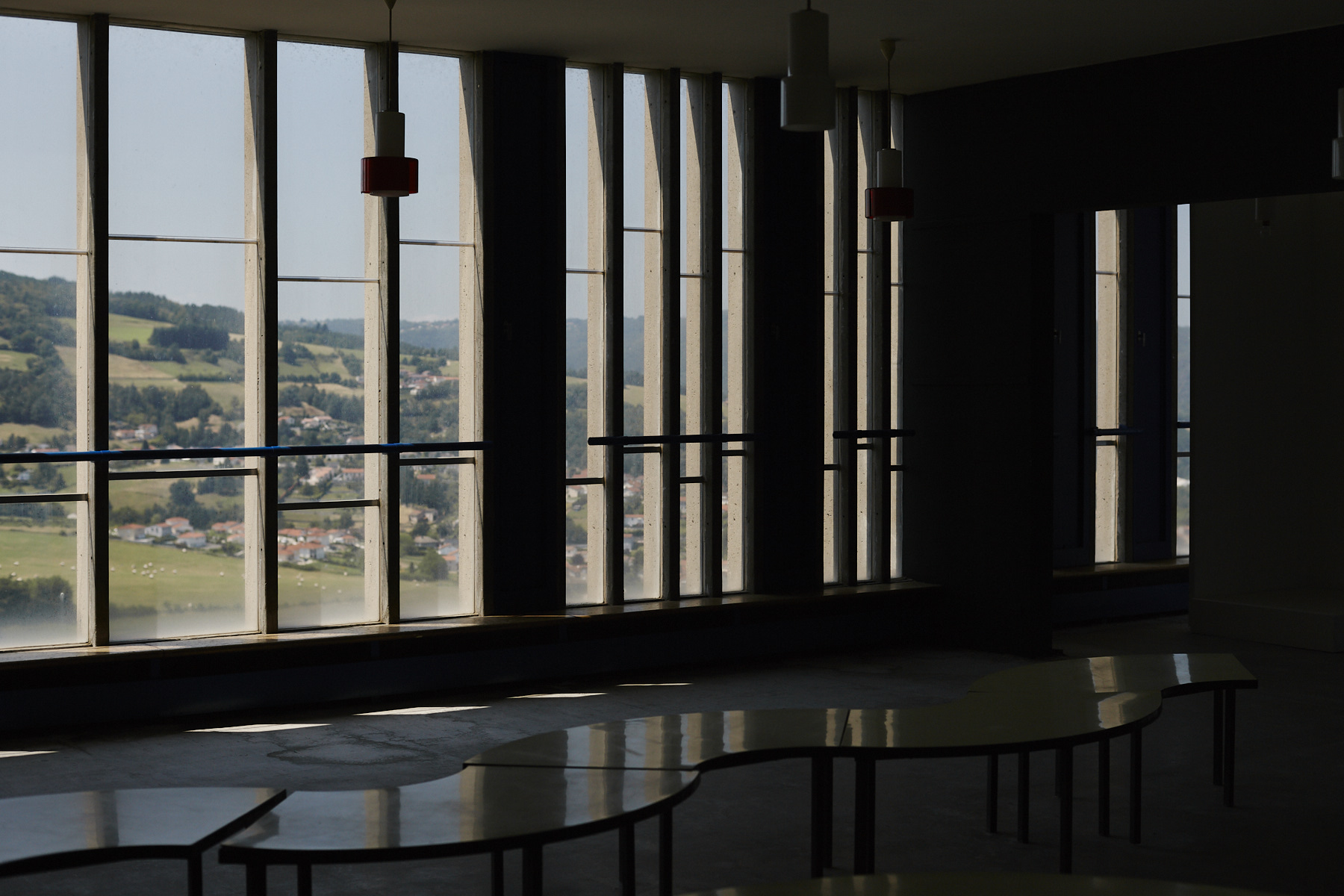

Through these high-rises, Corbusier sought to liberate the masses from the dark, stale and crowded apartments of the past. “Space and light and order. Those are the things that men need just as much as they need bread or a place to sleep,” he said. Meanwhile, a single building entrance and communal facilities would counter rising social isolation by increasing happenstance resident interaction.

In addition to private apartments, each Unité d’Habitation would feature all the services Corbusier deemed necessary for everyday life—a school, grocer, laundry, gym and a post office. Through this, Corbusier reduced the scale of a typical ‘city’ to a single Unité, where the hallways are ‘streets’ and the elevator is the ‘subway’.

Le Corbusier conceived five Unités d’Habitation total—in Marseille, Rezé-les-Nantes, Briey-en-Forêt, and Firminy in France, and one in Berlin’s west. Like many Modernist utopian developments, Corbusier’s Housing Units were positioned in outlying areas of cities or towns. When the first was completed in Marseille in 1952, it was surrounded by farmland. Today, the city has encroached on the Housing Unit’s position, which may have contributed to this particular build’s enduring success. It was and remains equipped with a rooftop terrace, grocer, hotel, restaurant, school, gymnasium, and office spaces.

However, it is only at Firminy that the Housing Unit is joined by additional community facilities—a cultural centre, stadium, church, and swimming pool, all envisioned by Corbu and his collaborators. Despite countless conceived concepts for improving the urban fabric (he’d drawn new plans for Paris, Antwerp, Buenos Aires, Algiers and Montevideo), Firminy is the sole example of Corbusier’s city-scale design in Europe—with Chandigarh in India the only other example globally. The multiple buildings in Firminy were among his last-conceived designs, with most structures completed posthumously.

However, the strategic vision for Firminy’s Unité d’Habitation was never fully realised. (It was common that developers or government authorities often changed Corbusier’s designs or cancelled the in-house amenities. For an earlier project in the mid-1920s, Corbusier designed a ‘city’ of houses for industrial workers at Pessac, but authorities found the design and colour scheme offensive upon completion, so they refused to route public water to the property and the houses sat dormant for six years.)

At Firminy, without a grocer accommodated into the building plan, a farmers’ market was proposed to pop up between the 30 characteristically Corbusian pilotis so residents could do their grocery shopping, but this never eventuated. The form for the rooftop pool was installed but never filled with water. And knowing that the rooftop was practically uninhabitable under the summer sun, Corbusier added a balcony to the west elevation, so that the school children continued to have access to an outdoor space on hot days.

The alternative Freinet school, however, ran successfully from 1968-1998, when it closed for lack of pupils. Here, children were encouraged to draw on all surfaces—the concrete of the balcony, the doors, and mobile room dividers served as backboards. This carried into the apartment design too, with sliding doors between children’s bedrooms acting as blackboards to write out homework.

For Corbusier’s own studio-apartment on the outskirts of Paris, he acquired the entire top floor (and rooftop) of the seven-storey Molitor apartment building that he designed with his cousin Pierre Jeanneret in the early 1930s. For the Immeuble Molitor, Corbusier demonstrated his philosophies on structural integrity, delivering a free plan with only the sanitary facilities fixed in place, so tenants could configure the walls within the apartments themselves. With the 240 square-metre penthouse to play with for his own personal living quarters, Corbusier did for himself what the current residents of his Unité d’Habitation in Firminy have done of late—enlarging the area by combining apartments and reconfiguring walls and rooms to better suit the changing dynamics of today’s ‘modern’ family. Among the 17 levels of apartments, the seven inner streets originally serviced 414 homes. Today there are around 300 apartments with dimensions more suited to contemporary desires.

UNESCO’s World Heritage Centre lists 17 of Le Corbusier’s works for his contribution to “a new architectural language”, including the buildings at Firminy. But the heritage listing refers only to the Unit’s exterior, pilotis, school and rooftop terrace, so the interior can be configured to evolving living requirements.

Did Corbusier expect that his architecture would still be valued and preserved today? An architecture that was designed to serve a moment, built in a material not as long-lasting or easy to maintain as one imagines? While Modernism sought to break with the past, perhaps he was considering how his physical legacy might be adapted to changing social conditions in the future: “To be modern is not a fashion, it is a state. It is necessary to understand history, and he who understands history knows how to find continuity between that which was, that which is, and that which will be,” he said.

As I write this story, I’m sitting in another modernist housing block in Lyon’s Croix-Rousse, designed by Pierre Tourret and completed in 1962. It mirrors Corbusier’s use of pilotis and the concrete frame. However, instead of a lodging traversing the entire east-west width of the north-south-facing block, this apartment only faces west—taking in a magnificent view, but causing an afternoon fury of sunlight to sharply flood all rooms. It’s warm, even on a mild autumn’s day. As I toured Firminy, my guide similarly admitted the Unité becomes uncomfortably hot inside amid our changing climate.

While not all of these buildings are in use as they were initially imagined, Corbusier’s vision for Firminy-Vert does continue to shape the wider town and its community. The public amenities have endured and continue to be utilised. The Firminy-Vert Stadium surrounds an athletics’ track and football field and was heritage listed in 1984 along with the Maison de la culture, which continues its original purpose as a space for musical and artistic creation and performance. The striking Saint-Pierre was built posthumously to original specifications and completed under José Oubrerie’s guidance in 2006. It hosts mass for the community and presents exhibitions on the architect and his collaborators. From the swimming pool comes shrieks of joy and loud splashes as I walk past—it formed part of the urban planning programme conceived by Corbusier, but was designed and completed by his colleague André Wogesncky in 1971, and heritage-listed in 2005.

While Corbusier’s philosophies, aesthetic and oeuvre attract vigorous debate—both then and now—his questions of form, light and shadow are omnipresent in today’s architectural toolkit. There are elements of his utopia that still feel utopian today, perhaps proffering clues as to unexplored terrain for living better and more communally. The issues of traffic and transportation, noise, green spaces, communication, healthier living and economic social housing that he sought to tackle with his high-rise cities remain imperative conversations today.

We all require shelter—ideally that which supports a great quality of life. So how do we learn from the past and present to shape future ways of communal living? And what will be so radical and perhaps polarising to be awarded heritage status, to be crowned a new language, in the future?

A warm thanks to Linsey for this modernist postcard from France. Linsey is currently travelling and writing and photographing – follow her adventures on her website. And this story is part of our exploration of (future) legacies, musing on what we inherit and what we leave behind.