Berlin’s spielplätze show the community value in play

Germany has some of the world’s most exciting playgrounds, thanks to a combination of social values and wise design regulations. On her sojourn in Berlin, urban planner Mitra Anderson-Oliver gets to explore (mit kind!) this essential infrastructure of childhood.

It should come as no surprise that the playgrounds in Berlin are incredible: playgrounds were invented in Germany. But somehow, with every new wondrous, adventure-filled visual delight that my son and I stumble across, I am amazed anew. And now, after six months living in Berlin, what surprises me is not the good playgrounds, but the crappy ones. If you look really hard, you can find them – forgotten spaces with not enough trees, maybe the swings are broken or the arrangement of the equipment is just a little too sparse to be truly inviting – but they are few and far between. For every famous spielplatz that scores a write up in the New York Times or Monocle Magazine, there are a dozen just-as-good paradise playgrounds that locals flock to.

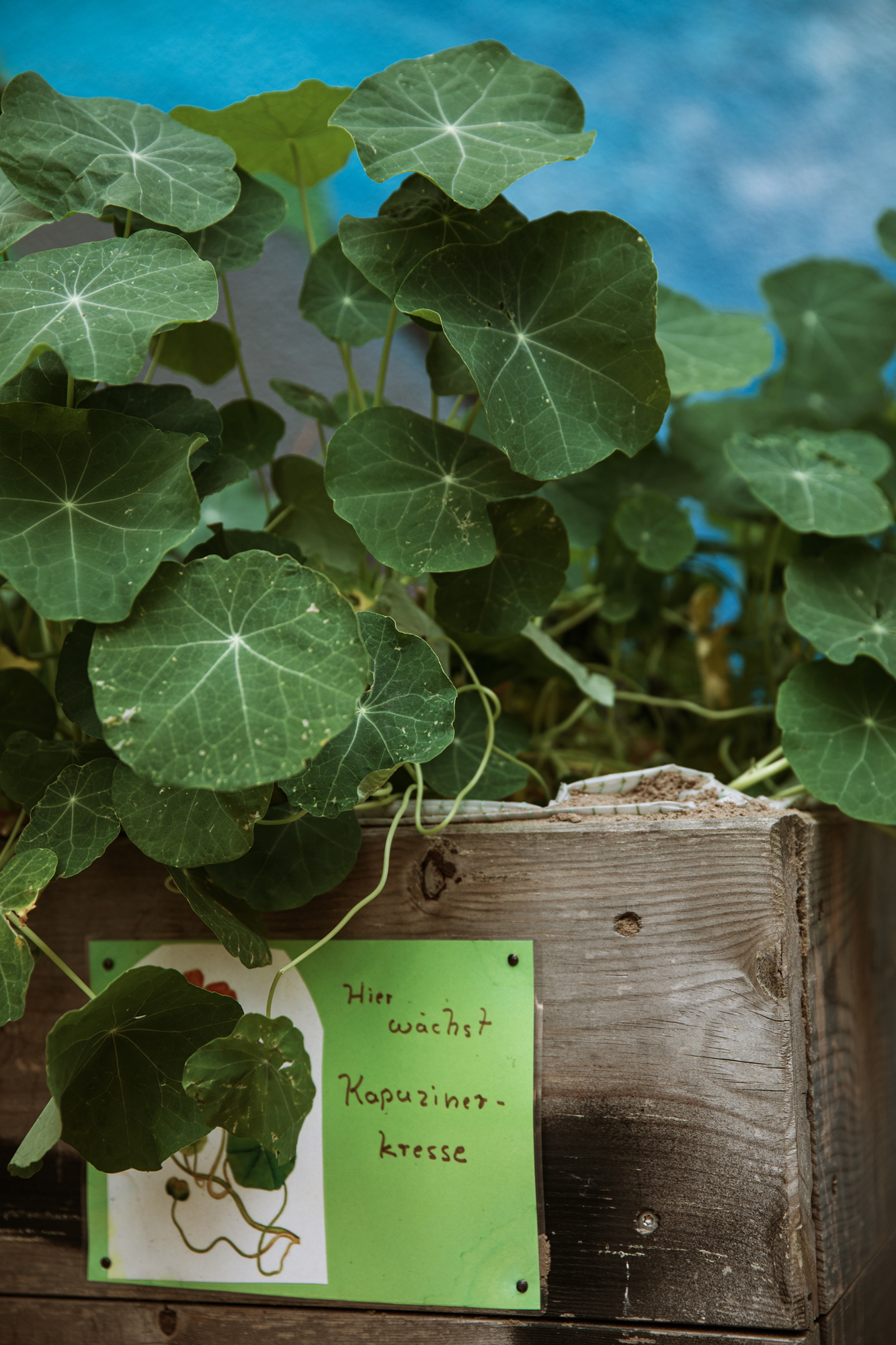

Our enduring favourite is a ‘pocket park’ adjoining the neighbourhood house Kiez Oase, about 150 metres from our back door. It’s small by Berlin standards – only about 500m2 – but most afternoons has upwards of 40 kids and their parents getting busy in the sand, queuing for the swing, serving make-believe ice-creams out of the window of the play house, or monkeying about on the more challenging beams and ropes. It’s shady, there’s a co-op café that opens out onto it, there are dozens of sand-play toys permanently scattered about for all the kids to share (most Berlin playgrounds have sand as their base – but this one also has a dedicated pit), and it’s right on one of Schöneberg’s main village shopping strips. So, basically, perfection.

Just around the corner is Hexenspielplatz (‘Witches’ Playground’), a much bigger playground with a zipline, two-storey slides, a complex-to-get-into and fun-to-slide-out-of ‘witch hideout’ and many other exciting semi-dangerous bits of play equipment long removed from, or never even imagined in, Australian playgrounds. Another gem on our regular route is the Feuerwehrspielplatz (‘Fire Station Playground’) in Kleistpark, which features an epic slide and an intimidating mesh climbing tunnel. Once, I was chided by a local parent for helping my toddler cross the three-metre-high metal bridge: “He can do it!” The parent was right, of course. Then there’s Gleisdreieck’s trampolines and wasserspielplätze (‘water playgrounds’) at the southwest edge of the epic railyard rejuvenation project and a lovely forested number in the heart of Kreuzberg, with hillocks and bridges, water pumps and wooden crocodile balance beams. All of these are within easy walking or public transport distance from our front door. We are absolutely spoilt for choice.

In addition to all the benefits to children, extolled as far back as 1870 by the ‘inventor’ of playgrounds (and also of kindergartens), Friedrich Fröbel, come the benefits of the parents having a safe place to go with their child during the day. Somewhere to enjoy the outdoors, each others’ company, and – most importantly, I think – just feel like a part of the city. This is huge salve to the isolating effects of early parenthood, where it is all too easy to feel like all the loveliness of adulthood (independence, agency, a social life) is on the other side of an impassable Lego wall.

As a parent in Berlin, I don’t just feel like a part of the city in its playgrounds, I feel like a valued part of the city. I feel that my experience, and that of countless other parents, carers and children, is important. The spielplatz should be fun. It should be adventurous. There should be lots of sand, some water pumps for making messy, intricate dams and rivers, and some quite dangerous-looking climbing apparatuses, fit for all ages and stages. It should be shady with ample seating. There should be a kiosk or café nearby selling affordable snacks, ice-cream and beer (yes, beer). There should be variation. There should be beauty. And they should be free, all 1853 of them.

It’s important to understand that Berlin’s playgrounds were no accident. There are some key moves that we could start to make in Australia to bring a little more wonder and beauty into the daily lives of kids and their minders.

Of course, some of the factors behind Berlin’s generous playgrounds are specific to the city’s history and cannot be replicated, such as the sheer amount of empty space that used to exist as a result of World War II bombings. The subsequent emptying out of the city was compounded by the Berlin Wall, dividing the city population into East and West for over 40 years, condemning the German capital to a centreless, half-speed economy that struggled to regain its 1939 population high of 4.3 million. Berlin’s population growth is picking up pace now, with 3.6 million inhabitants at last count, putting major pressure on housing availability and affordability – and the remaining free space in the city.

However, courtesy of the 1979 Children Playground Law, there are 220 hectares of ‘usable playground space’ reserved in Berlin; a sizable figure, falling just short of the prescribed 1m2 per inhabitant (though the city is meeting its planning target of 6m2 of green space per inhabitant). This incredible, long-standing law also includes requirements for where playgrounds are located (near dwellings, adjacent to green spaces, sports and leisure facilities, protected from exhaust fumes, and in sunny rather than permanently shaded locations). They are to be planned, developed and managed by district “playground commissions”, which involve “parents, pedagogues and other professionals”. The law stipulates a “play offer that is varied, ideally usable in all seasons” and attentive to the needs of different age groups and abilities, all with the aim of “giving children the opportunity to develop psychological and physical capabilities, and promoting socialisation”. It requires the regular inspection of playgrounds, and that infrequently used playgrounds and play equipment be “improved or replaced”. The size of playgrounds and the type of equipment is also covered: from the minimum of 150m2 for a playground for children under six years, to the vast 2000m2 multi-functional spaces for older children and young people, which are to include skating and cycling ramps, table tennis and similar attractions.

Once these multi-purpose designs are in place, falling and getting hurt is not going to land anyone in court: as a rule, public liability in Germany is very limited. Independence, personal responsibility and a corresponding belief that exposing kids to a certain amount of ‘acceptable’ risk is a really important part of their development are values deeply embedded in German society – and this is reflected in their legislation around play spaces. This frees up playground designers and city authorities to be more daring, challenging and playful in their designs.

While these regulatory settings may seem a long way off in Australia, there are other things we can get started on immediately. For example, proactively seeking out partnerships with state and local governments to reserve space for, and participate in the making of, playgrounds. One such initiative is Raum für Kindertraüme (‘Room for Children’s Dreams’) by the Berlin district Spandau, which builds and renovates playgrounds with the local community, and Drachenland (‘Dragonland’) in Friedrichshain, which was planned together with residents and children and completed in 2002. A children’s design competition was held to determine “the most beautiful dragon”: a huge, coloured wooden beast which now watches over the children as they play.

There are also many examples of direct action, with the community taking over neglected civic spaces or common areas and fundraising for the building of playgrounds themselves. This has resulted in some of the most fantastic and popular playgrounds in Berlin, such as the adventure playground Kolle 37 (only allowed to be built by children themselves!), and the renovation and doubling in size of the play area at Lausitzer Platz in Kreuzberg. Community-created and -managed playgrounds go that extra step of building a sense of ownership and belonging to place that so many of us crave in our oftentimes disconnected and atomised urban life.

When designing new public playgrounds, we could also support and advocate for local companies that make beautiful, modular structures with sustainable materials. In Berlin, two major suppliers, SIK-Holz and Merry Go Round, rely almost entirely on wood for the construction of playgrounds; sustainable, carbon-sinking, easily-arrangeable-into-so-many-exciting-variations, lovely to touch and climb on, wood. They source much of their timber – robinia pseudoacacia or ‘false acacia’ – from the Black Forest, and assemble it onsite in bespoke variations, sometimes based around a theme (such as at Hexenspielplatz), an age group or activity set. A special quality of robinia wood is its natural strength and elasticity, meaning that it requires no chemical treatment before being used in playgrounds. Irregularities in growth, grain, growth rings, knots and roots are celebrated, and are said to “give the impression that it has been designed by children”. There are many fantastic playgrounds in Australia – such as the wonderful Wombat Bend playground on the Yarra River, Agency of Sculpture‘s stunning ‘Eddy’ on Mount Beauty and Playce’s Valley Reserve in Mount Waverley (all in Victoria), and the community co-designed ‘Train Park’ in West Hobart, Tasmania. It’s about picking up on these trailblazers and supporting their efforts to introduce greater variety and quality into our play spaces; not just for a single feature project, but as the standard across our cities and towns.

Living on the other side of the world with a young family, I’ve missed my friends and family, as well as my local haunts. But when I do finally come home, it’s not going to be the long Berlin nights (rare for me these days!), fresh falafel or the incredible public transport system that I’ll miss the most. It will be these abundant, exciting, inviting spielplätze, and all the love for people that they embody.

(Final note: just last year a directory on Berlin’s playgrounds was finally published by a keen local, listing 34 playgrounds across the city, with beautiful pictures, short descriptions and handy maps including the closest u-bahn stop and ice cream store. If you are heading to Berlin, mit kind, you can pick one up here.)

Thank you, Mitra, for this magnificent story of play in the city. This article also appears in our new print issue #12: (Future) Legacies. Join us as we reveal the issue on 15 November at MPavilion – and pick up your own (free) copy!