Eating the invasive species problem in Australia

Artist Kirsha Kaechele embraces complexity and contradiction that permeates attempts to do good in the world. Her art projects range from gun buyback programs to cleaning up rivers, and do not necessarily look like art to anyone but her. In her new project for Mona, she is proposing to solve the invasive species problem in Australia – by eating them.

When Kirsha Kaechele arrives at our interview she asks if anyone has a jacket she can borrow. “I have one,” I offer, “but I’m afraid it’s leather.” “Oh, is it invasive deer leather?” she asks. I tell her it’s second-hand, so I really don’t know, but I doubt it.

“That’s fine,” she says. “I’m a complete hypocrite. I’m not a puritan, but sometimes I get inspired and try to live really well.”

But Kirsha doesn’t strike me as a hypocrite, not even close. She strikes me as someone who is trying to live deep within complexity and accept the contradictions and paradoxes involved in being human — while having as much fun as possible. I feel that if she were a pig, complexity would be the muck she wallows in. But Kirsha, of course, is nothing like a pig. (Unless you think of pigs as Roald Dahl does, you know: pigs are noble, pigs are clever…) She has, however, just spent five years thinking about pigs — and deer and pythons and the leaf-cutter ant — as part of a project about invasive species that attempts to create a new approach to living with and in the environment.

“If you, as a human, see that one species is wiping out all of the others, you could say, all at once, ‘that’s part of the larger dance of nature’, and also ‘I don’t want to lose all those other species in my backyard’. What I’m saying is, look, this debate doesn’t really have an answer.”

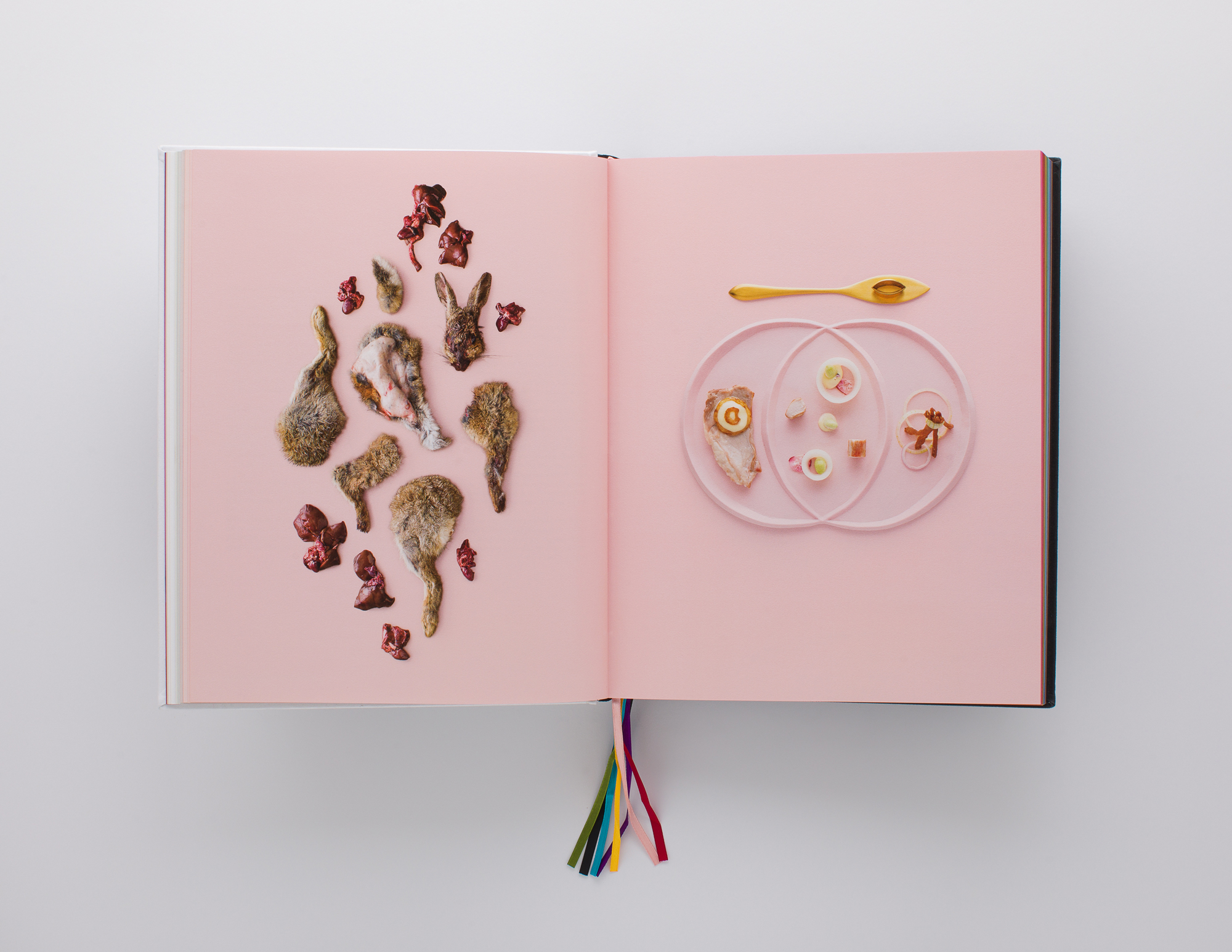

Eat the Problem is both an exhibition and a monumental 544–page surrealist book. The book is filled with ‘recipes’ on how to cook (or makes clothes with) invasive species, including cane toad, camel, stinging nettle, Japanese knotweed, sea urchin, Burmese python, human, and feral pig (or wild boar). From the selection of intriguing, repulsive, and delightfully absurd recipes in the book, Ragu di Cinghiale (wild boar ragu) is one that you could actually make. For Kirsha, the project is all about transformation and continues her approach to art as a process of turning a flaw into a feature — or, as Kirsha puts it, “turning shit into gold.”

Kirsha has had an unconventional life. She grew up in Guam, as a minority white girl in an indigenous Chamorro neighbourhood. When she was in her late teens, her father died and she embarked on a seven–year journey, visiting over 50 countries in search of enlightenment. She spent time with and learnt from people including Biosphere 2 creator John P. Allen, chemist Albert Hoffman, writers Tom Robbins and John C. Lilly, poet John Perry Barlow, psychiatrist Oscar Janiger, and artist Peter Nadin. She also visited shamans, took plenty of mind-altering substances, and almost joined a cult; but she ended up in New York, feeling lost and unenlightened.

It was art that finally saved her. “Art helped me become a member of society again. You can be a member of society while still being an artist, which accommodates a process that allows you not to be sure about reality, or to deal with your own questions around that. I’m happy I exist now. I’ve come to terms with it. I accept society and I take delight in all the contradictions and strange things that happen.” Accepting those contradictions gives Kirsha an approach to life that embraces a wonderful shamelessness and leads to moments of beauty – and at times results in art.

In 2000, Kirsha moved to New Orleans and bought a run–down old bakery, which she turned into a living and art space, and launched KK Projects and the Life is Art Foundation. In addition to her own projects, she curated exhibitions that brought the work of international artists such as Robert Rauschenberg, Tony Oursler and Mel Chin to New Orleans, throwing huge, themed dinner parties on opening nights. She hosted one such dinner for the patrons of Warhol Foundation in 2006, setting up a long table down the centre of her street. It just so happened that her street was in St. Roch; a poor, all-black neighbourhood.

Against the wishes of the Warhol Foundation, Kirsha secretly found a way to invite her poor, predominantly African American neighbours, to the dinner — either as guests or to work at the event, their choice. This caused a huge controversy with the Foundation folks — some of whom were confronted by the reality of their class difference, and refused to attend. It hurt Kirsha financially, but also generated moments of great beauty. “What’s beautiful is when, at the same table, you’ve got a Swiss banker and a gangster and they’re having a meaningful conversation across class barriers. It sucked to be villainized; but being villainized has never been enough to make me stop doing the work that I believe in and find rewarding.”

“When I’m making art, the people I’m collaborating with often don’t even know that it’s art for me. And the fact that it’s art for me doesn’t negate that it isn’t for them.”

Kirsha’s work inhabits a space between art and life: “I don’t know how to explain what it is. All I can say is that I know, at moments, ‘this is art’. I think it’s just about a way of seeing that takes hold; you don’t really control it. Sometimes I’m making art and sometimes I’m just running a garden program.”

In New Orleans, Kirsha’s Life is Art Foundation began with Kirsha planting an open garden. As the local kids began to hang around, Kirsha and her collaborators got them involved and taught them how to plant and grow vegetables, which turned into the kids starting a business and selling their vegetables to some of the best restaurants in the city. Another project was CA$H 4 GUN$, a gun buyback art performance staged in a car wash and sweet shop in New Orleans. Since moving to Tasmania to live with her partner David Walsh, founder of Mona (Museum of Old and New Art), Kirsha has created the Heavy Metal project, using oysters to filter heavy metals from the Derwent River which are then buried in a ‘Mausoleum’ at the end of their life; an art and hacking school for young people in New Orleans; and 24 Carrot Gardens, “a kitchen garden program that teaches children from schools around Tasmania and communities in New Orleans to grow, harvest and cook healthy produce.”

Kirsha’s process–based approach to art stems from a desire to engage in conversation and collaboration, together with an awareness that everyone is coming to the project with different motivations. “When I’m making art, the people I’m collaborating with often don’t even know that it’s art for me. And the fact that it’s art for me doesn’t negate that it isn’t for them.” While these projects may result in practical, positive changes in people’s lives or the environment, Kirsha’s interventions are definitely not driven by do–gooder impulses. Kirsha’s desire is to create beauty, which for her is “movement, collaboration and exchange of energy between zones that are traditionally kept apart.” But that beauty is not just a matter of visual aesthetics, she says. “It’s also aesthetically repulsive to have a missionary message.”

“There’s something one-dimensional about heavy-handed environmentalism.”

And that is also Kirsha’s approach to the current environmental crisis. As her latest art project, Eat the Problem confronts questions of environmental sustainability from an irreverent, playful perspective. Kirsha believes the environmental movement needs a makeover. “There’s something one-dimensional about heavy-handed environmentalism. It’s dualistic, and that’s not rich enough. The question is: how can you be both environmental and have space for all of this complexity? Complexity is ecological. It’s about getting away from the black-and-white, right-and-wrong position, which perpetuates the duality and makes people who are not environmentally–minded hate environmentalists.”

It’s a systems based approach to art, and to life in general, and resulted in Eat the Problem transgressing some wild and unexpected territory. Presented as a luscious, irreverent, tongue–in–cheek cookbook about eating invasive species (which we might generally think of as animals, insects or weeds), the project also traverses questions about human engagement with magic, drugs, the Catholic church, fascism, extra-terrestrial life and artificial intelligence. How are these invasive species? Well, they are all processes, actions or life–forms that do (or could) invade and destroy otherwise intact ecosystems. Seen from another perspective, it’s all just nature. “That’s what was so interesting to me,” Kirsha explained, “and why I was able to continue on this project, because that question remained unanswered — and it still doesn’t have a clear answer.”

True to Kirsha’s love of process, the book reveals a deep honesty — a bold shamelessness — in her acceptance of the flaws of our human nature. With striking irreverence for the social mores of polite society, Kirsha openly chides Natalie Jeremijenko (who didn’t contribute to the book) for not answering her phone, and prints David Walsh’s email exchange with Tim Minchin in which he literally bribes Tim into contributing to the book. This revelation of somewhat shameful processes, that most people would have the impulse to hide, beautifully illustrates Kirsha’s radical ‘art is life’ attitude.

Fittingly, then, the accompanying exhibition is based around experiences, including treatments such as CranioSacral Therapy, reflexology and Thai massage. “Because it’s about transformation,” Kirsha says, “shit into gold, flaw into feature. It goes all the way down to your own shit. Not literally, but your stuff.” The ‘set’ for the exhibition is a sculptural feast table, laid with bespoke ceramics and cutlery, all designed by Kirsha: “[It] is also the world’s largest glockenspiel, and is made out of invasive camel hump fat from culled camels, invasive deer fat from our own property where they’re wreaking havoc, invasive wild boar and also tapioca.”

The feature events of the project are a series of colour–themed feasts in which guests come dressed as a colour, eat the colour and then move through a range of flavours across the colour spectrum. Including brown, or, as Kirsha puts it, ‘the shit course.’ “I liked the idea of a course where you would eat indigestible fibre, which someone like Heston Blumenthal is really into, because of the gut microbiome. I love the gut microbiome, and how it’s kind of a brain. Talk about symbiosis! We’re apparently 50% not-us. We’re only 50% our own selves: the rest is all result of these symbioses of everything that we’ve evolved with and are connected to.”

By challenging us to look at the realities of our world from different perspectives, Kirsha offers an invitation into her transformative way of thinking, into a process of open experimentation. “It’s an improvised process, and you don’t know what the next step is. When you’re working with this mess, something’s happening that’s dynamic, not static, so you feel inspired to respond. And that results in a conversation.” For Kirsha, the aim is not to overcome and resolve complexity, but to find ways we can embrace it and transform it into something beautiful.

“It’s all about leaping over and transcending the philosophical quagmire, when there’s no answer about what is better – to do or not to do. If you, as a human, see that one species is wiping out all of the others, you could say, all at once, ‘that’s part of the larger dance of nature’, and also ‘I don’t want to lose all those other species in my backyard’. What I’m saying is, look, this debate doesn’t really have an answer, but if you’re going to decide to take that weed away, then how can we make that weed a resource? How is that going to replace something else that you really need, especially when procuring that thing damages the environment’?

“When you can replace something that you’re using anyway, with a weed that’s superabundant, then that removes the debate, and the guilt —the moral quandary — of imposing your will on the ecosystem. So then you can kind of have your cake and eat it too. And that’s what I’m all about.”

A huge thank you to Kirsha, Emma, Emily and the team at Mona for bringing this stimulating conversation to Assemble Papers. Eat the Problem exhibition and event series runs at Mona until 3 September 2019. There is also a fabulous book. Kirsha’s dinners are now ‘invading’ the mainland and can be booked here.