What it takes to close the loop on food waste

Our series ‘Circular Thinking’ brings together insights from our workshops on the circular economy. In our last instalment, we look at what it takes to close the loop on food waste, with Kirsten Larsen and Jen Sheridan from Open Food Network.

If you think food waste is a small matter, think again: if food waste were a country it would be the third largest greenhouse gas emitter, coming in just behind the USA and China. One third of all food is wasted – either going directly from fridge to landfill or going to waste on farm. For example, 25% of vegetables produced don’t even leave the farm, due to market factors such as cosmetic standards or the market price not even covering the labour costs of harvest. And although fruit and vegetables are organic matter, which can decompose or be used for compost, this is unfortunately not what happens: worldwide less than 2% of nutrients in food waste is reused. The rest often ending up in landfill, where they create further emissions as they decompose. What a waste.

The food industry is one of the most globally integrated ones: according to Oxfam’s ‘Behind the Brands’ project, 10 companies control most of the food and beverage supply around the world (including in Australia) while 80% of Australian food is sold through two supermarket chains. These are powerful market players, able to decide the fates of farmers around the country – as well as dictate what we consume, how much packaging we buy with our food, and how far it will travel. It didn’t use to be this way: cities used to produce much of their food locally. Cities often grew around productive agricultural areas: even great metropolitan regions, such as Paris or Tokyo, were historically ringed by productive ‘foodbowls’ that helped feed the city’s population. Today, this productive land – with some of the world’s best soil – is threatened by sprawl and industry.

Melbourne is an excellent example of how circular our food systems used to be. The city was virtually self-sufficient in fresh vegetables until World War II. The market garden farms in Melbourne’s foodbowl still produce a wide variety of fresh food, and have the capacity to supply up to 41% of Greater Melbourne’s food, including over 80% of our vegetables. However, this productive farmland is being displaced for new housing, and the legacy of innovative city planners, who protected the city’s ‘green wedges’, is at risk.

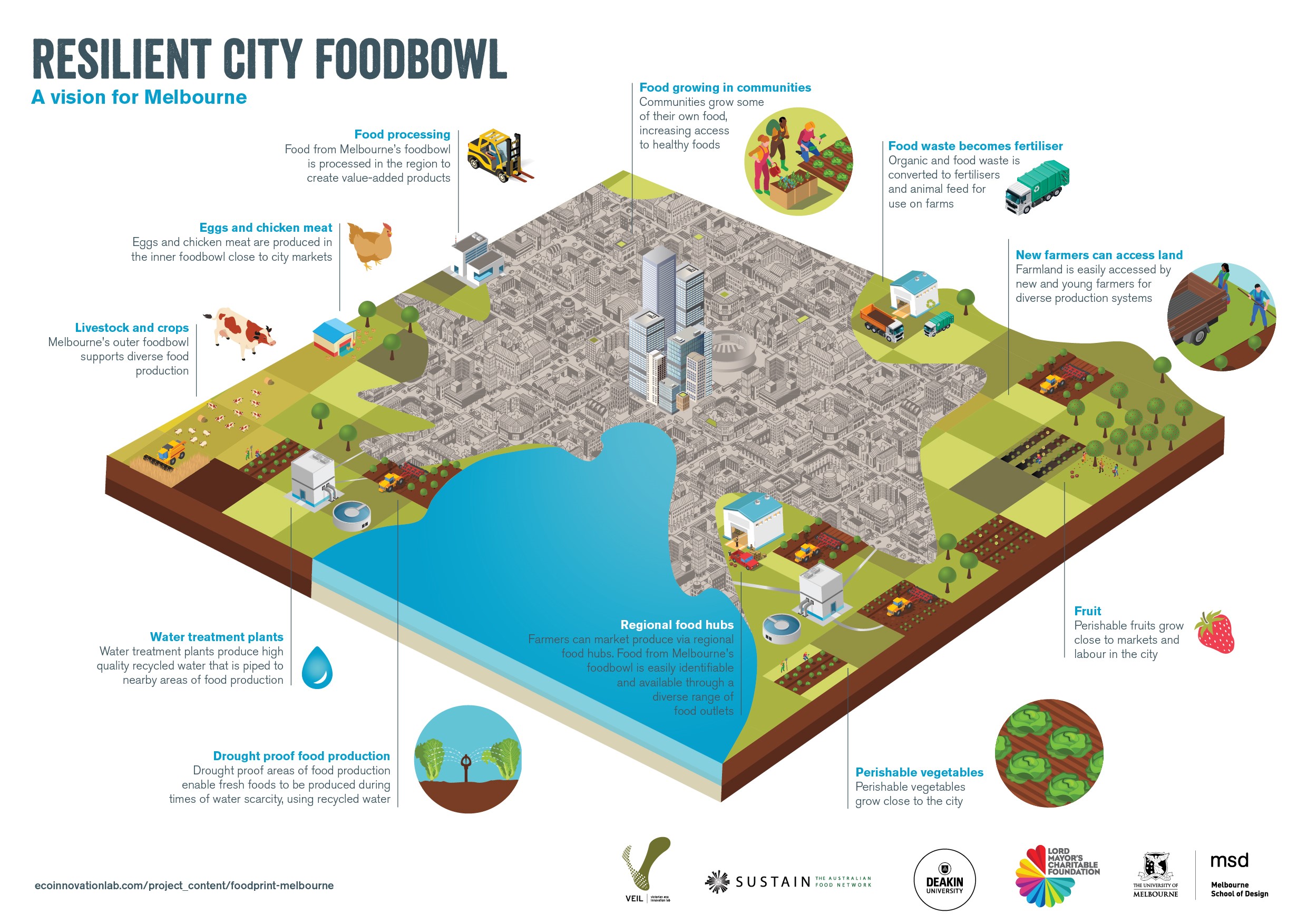

The symbiosis of city and surrounding farmland is one of the clearest examples of how circular economy can ‘close the loop’ between industries, making one person’s waste into another’s valuable resource. Farmers close to cities have access not only to markets, but also workers and transport infrastructure. If we plan our cities well, they can also have access to water and nutrients from city waste streams, and organic waste that could be processed into compost and biofertilisers. Called ‘nutrient recycling’, this is a much more productive use of food waste than incineration. Cities, in turn, get fresh local food.

Prompted by the belief that there had to be a better way to give farmers a fair price for food rather than keep them beholden to global companies, and that enabling farmers to work together to sell produce could help build a better food system, Kirsten Larsen and Serenity Hill founded Open Food Network. It started in 2012 as a little experiment, with a van, some farmers and some friends, but it has since then grown to become an open source platform nurtured by like-minded people around the world. Open Food Network connects local fair food traders, food groups and local food networks through an online marketplace. Producers can open and run an online shop through the Open Food Network website or connect to food hubs and wholesale networks. Kirsten and Jen Sheridan (community facilitator at Open Food Network) are also researchers in the Foodprint Melbourne project at the University of Melbourne, which has created a roadmap of actions to protect Melbourne’s foodbowl.

How do we become good food citizens? Kirsten and Jen recommend starting from our own food choices. There are now increasingly farmers that use organic, bio-dynamic and regenerative agriculture methods – which not only maintains, but improves the quality of the soil. Wherever possible, source your food locally and from regenerative farms, and pay farmers a fair price for producing food sustainably. Make the most of the food you do buy: minimize packaging, eat it all (!), and compost and regrow as much as possible. And support your local farmers by getting involved in a local food network. When farmers are able to network directly with consumers, it allows them to plan crops through pre-sales and coordination between farmers, and usually dramatically improves their financial viability. It makes for less waste, and less stress.

We can also advocate for new ways of planning for cities that put a value on food production. City foodbowls have access to wastewater and organic waste that can increase farms’ resilience to environmental pressures of growing food, and climate change. In turn, they can recycle urban waste. When cities and urban farms grow together, they create circular food systems that ‘close the loop’ on valuable resources from city waste, by returning these to the soil. According to the UN, it is expected that 68% of world’s population will live in cities by 2050: it is time to build circular food systems now.

We want to thank Kirsten and Jen for introducing us to circular food systems. If you are keen to get involved, Open Food Network lets you connect to local fair food traders, groups and local food networks. You can find more information how important all city fringe farmland is both now and into the future from the Foodprint Melbourne project. Victoria’s Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP) is currently seeking out opinions on protecting Melbourne’s ‘green wedges’. Tell them what you think Melbourne should do with its strategic agricultural land – submissions close this month.