Exploring future utopias and dystopias of the home

In 1964, Dionne Warwick sang plaintively that in her lover’s absence, “a house is not a home”. Eight months later, British critic Reyner Banham suggested in Art in America that “a home is not a house”. The profusion of mechanical services had reduced domestic architecture to a technological support system. The lyric was tweaked again in 1967, when Arthur Lee and Love recorded the paranoid Sunset Strip psychedelia of ‘A House is Not a Motel’. All three formulations resonate today in unanticipated ways. When digital networks and mobile devices have untethered our social relationships from patterns of physical proximity, when the gig economy and a widening renter-owner divide have left an email address more permanent than a real address, and when Airbnb has transformed houses into actual motels, what does the idea of home even mean?

Last October, IKEA published its fifth annual Life at Home Report. Previous iterations have explored the private moments and collective rituals that play out in the domestic environment, delving into our morning routines, how we eat and prepare food, and the common tensions that disrupt the rhythms of shared living. The most recent edition, which draws on a sample of almost 23,000 people in 22 countries, addresses a more intangible question: what is it, exactly, that makes home feel like home? An unsettling trend emerged from the survey data, when it was compiled back in London: thirty-five percent of city dwellers said they felt more at home in places other than the space in which they actually lived—a mass retreat to literal homes-away-from-home.

Home Futures: Living in Yesterday’s Tomorrow, currently on view at London’s Design Museum, explores this question by revisiting speculative visions from the past. The exhibition presents a range of techno-utopian fantasies and dystopian anxieties that not only comprise a time capsule of once imagined futures, but also cast a critical gaze over the realities of the present. Our homes represent both physical spaces and a way of life—our sense of self refracted through the wider shifts that shape evolving trends in architecture and design. With Home Futures, curators Eszter Steierhoffer and Justin McGuirk situate everything from Hong Kong micro-apartments to the Amazon Echo in a continuum of twentieth-century dreaming.

While material from earlier eras makes an appearance—perhaps most enduringly, Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky’s mass-produced ‘Frankfurt Kitchen’ from 1926, which applied modernist theories of efficiency and hygiene to domestic labour—the exhibition dwells largely in the period running from the mid-1950s to the late 1970s. It’s a fertile sweep of (Western) history that begins with the rise of a new post-war consumer society, is turned upside down by the countercultural seeking and anti-materialism of the 1960s radicals, and culminates with the aftershocks of the 1973 oil crisis and burgeoning global environmental movement. It also includes an era of avant-garde design that has been having a moment of late, as the provocations of Superstudio, Archigram, Ant Farm, Haus-Rucker-Co, Ettore Sottsass, Hans Hollein et al have been celebrated anew in a series of exhibitions and publications.

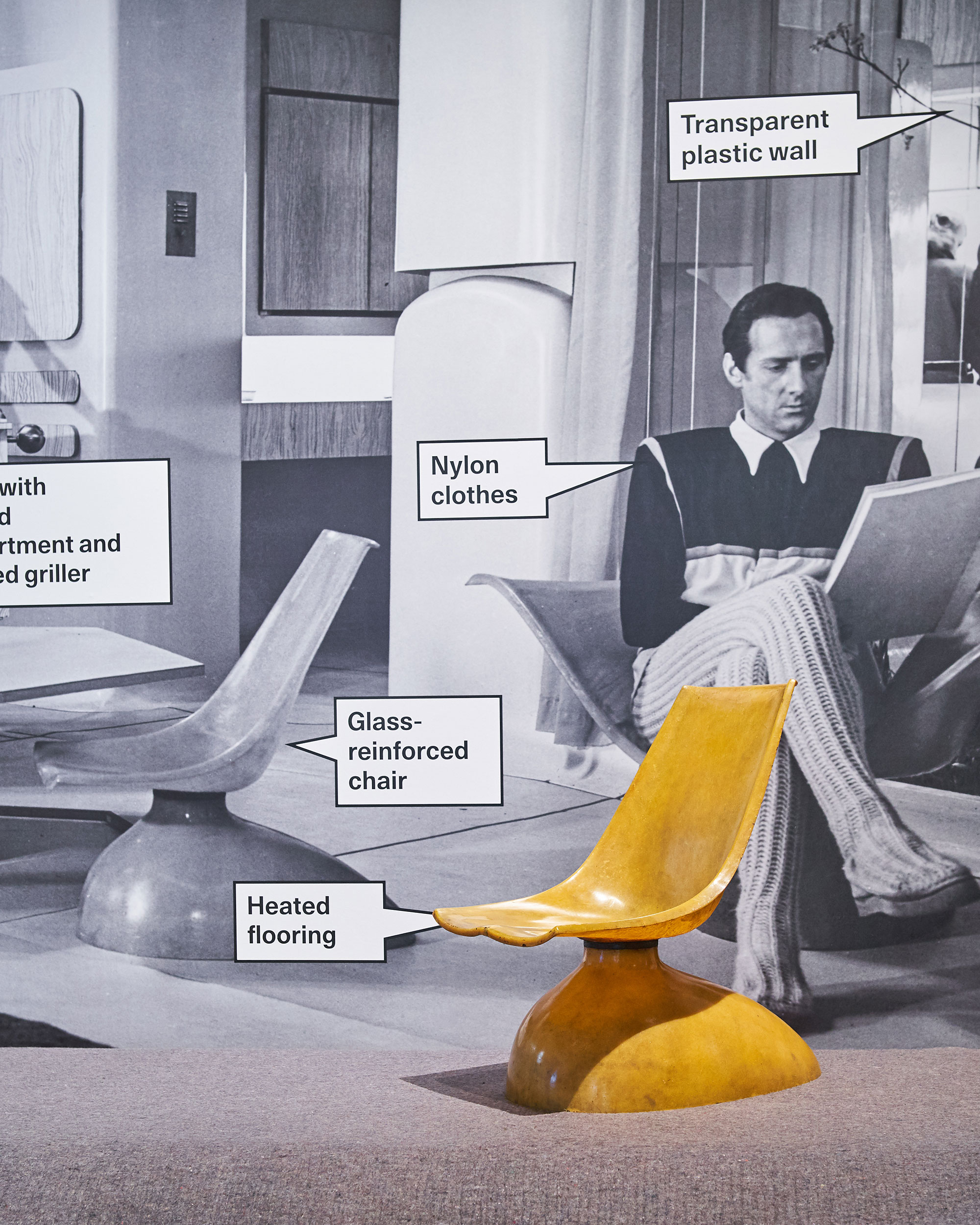

Much of this recent enthusiasm no doubt hinges on the arresting imagery and subversive sensibility. But the transition from Alison and Peter Smithson’s space age ‘House of the Future’, designed for the Daily Mail Ideal Home Exhibition in 1956, to the ‘admonitory tale’ of Superstudio’s Supersurface, first exhibited as part of Italy: The New Domestic Landscape at the Museum of Modern Art in 1972, encapsulates a broader change in attitudes towards technology, the family, capitalism, ecology, and community. When I asked Steierhoffer, she explained: “While the 1950s rendered a utopian future through the image of the push-button home, visions from the 1970s were often positioned in contrast to those earlier utopias. An increasing number of designers responded to the social and economic crisis of industrial societies: the 1970s saw less optimistic and more critical projects”.

Rather than a chronological survey, the case studies, prototypes, models, drawings, art works, and films included in Home Futures are organized around six themes: living smart, living on the move, living autonomously, living with less, living with others, and domestic arcadia. Though grounded in the past, these concerns engage directly with debates about the changing nature of today’s home, including ‘smart’ technology, mobile lifestyles, off-grid living, sustainability, shrinking space, and shifting notions of privacy. Visitors move through a series of rooms designed by the architectural practice SO-IL, inspired by the curving, floor-to-ceiling translucent nylon that Lithuanian-American artist Aleksandra Kasuba built inside her New York brownstone in 1971, redrawing the generic floor plan to create a sensory ‘Live-in-Environment’. In the expansive spaces of the museum, semi-transparent mesh partitions produce a similar porosity and fluidity.

Italy: The New Domestic Landscape (MoMA, 1972) is now considered a seminal exhibition, for its regard for design not merely as a creative product, but also, according to curator Emilio Ambasz, as “an exercise in critical imagination”. At the time, Ambasz commissioned a series of ‘Environments’ proposing radically different forms of domesticity. Projects by Sottsass, Superstudio, and Joe Colombo are included in Home Futures, and appear remarkably prescient almost half a century later. Colombo’s ‘Total Furnishing Unit’, which unified the functions of the home in a 28-square-meter flexible module, prefigures the recent focus on prefabricated micro-homes as a possible affordable housing solution. Superstudio’s Supersurface, meanwhile—an enveloping, universal grid to support networked nomadism—reads as a metaphor for plug-in lifestyles in the internet age.

Two contributions from the Italian architect and artist Ugo La Pietra appear even more prophetic. In ‘La Casa Telematica’, originally designed as an installation for the Salon del Mobile in Milan in 1983, cameras and screens have infiltrated every inch of the home, functioning as the portal through which we experience daily life and broadcasting our most intimate moments out into the world. When the blue glow of a smartphone screen is the first and last thing most people glimpse each day, the future would seem to have arrived. An earlier project in Milan, ‘Living is Being at Home Everywhere’, involved the public performance of domestic rituals like shaving and sleeping, and the hacking of urban infrastructure to create temporary open-air living ‘rooms’.

In many ways, the structuring device of Home Futures is the tension between these ‘negative utopias’ and the Jetsons-style futurism championed by industry and fuelled by Cold War boosterism—from the ‘RCA Whirlpool Miracle Kitchen’, exhibited at the American National Exhibition in Moscow in 1959, to the ‘Monsanto House of the Future’, a Disneyland attraction visited by more than 20 million people between 1957 and 1967. But the reality is more complex. The anti-establishment counterculture of the 1960s and 1970s directly influenced foundational developments in personal computing and network technologies that have become so ubiquitous and consequential today. In the figure of Stewart Brand, for instance, it’s possible to trace a through line from Ken Kesey’s Acid Tests, via the Whole Earth Catalog, to Silicon Valley’s gospel of ‘digital utopianism’.

Writing in the Home Futures catalogue, technologist Adam Greenfield notes that in design terms, the contemporary home is ‘astonishingly conservative’. This certainly rings true in Australia. The average house has expanded in size by 30 percent since the 1980s (to become the second largest in the world after the United States), but little has changed in how that space is organized, beyond an embrace of open plan living. In part, this suggests a degree of comfort with continuity. It also reflects the risk-averse nature of developers and homeowners alike. The former have little incentive to experiment or innovate (except on cost). And personalizing your home is a gamble when it doubles as your most valuable asset. All the while, architects are largely sidelined as luxury service providers. Even when designers are given license to dream, an attachment to convention remains—witness the current Rigg Design Prize.

One of the most striking contributions to Home Futures is by the Brussels-based architectural studio Dogma. Loveless: The Architecture of Minimum Dwelling revisits 48 examples of the Existenzminimum, from the monastic cell to contemporary co-living developments. Taking a long view, the project points to the primacy of economic shifts and evolving patterns of work in driving changes to home life, as society and designers adjust to new realities; be it industrialization, the emergence of the nuclear family as a social unit, or recent trends to forego or delay home ownership, marriage and children. In a broader sense, Loveless makes clear how an alternative housing typology can function as either a tool of social emancipation or profit extraction, depending on related systems of ownership and domestic organization.

But the spatial familiarity of our home environments should not be confused for inertia. The final room in Home Futures is devoted to our irrational and emotional (that is, human) needs—a peaceful vision of the home as domestic arcadia that runs counter to modernist dreams of a “machine for living”. Among the exuberant biomorphic forms, what caught my eye was a cluster of sculptural objects. Closer inspection revealed they were the work of figures like the Brooklyn-based textile artist Doug Johnston and ceramicist Helen Levi. Rather than decorative artefacts though, they had been produced as part of Google’s ‘OnHub Makers’ project, which invited designers to imagine ways in which a wi-fi router could become the centrepiece of a living space (maximizing its performance), by concealing it in a customized ‘shell’.

Marshall McLuhan famously argued that we “look at the present through a rear-view mirror; we march backwards into the future”. Writing in the 1960s, he was referring to our tendency to grasp for existing analogies or functional equivalencies to explain a new medium or technology, even as it proceeds to reshape our environment in a way we cannot yet fully comprehend. The symbolism of attempting to ‘humanize’ the domestic node of a vast digital infrastructure network by cloaking it in the comforting form of an analogue handicraft is almost too perfect. It’s also a momentary blip. According to Steierhoffer, “the most dramatic transformations in the home—due to emerging ‘smart’ technologies—remain behavioural. At the same time, a growing number of traditional domestic objects are disappearing and slowly being replaced by invisible, immaterial alternatives”.

The dematerialized home of the near future will be shaped by software, not hardware. And soon there’ll be no need to hide the router in a fake vase. Last May, after flirting with Apple and Google, Lennar Ventures, the largest homebuilder in the United States, announced it had entered into a partnership with Amazon. New builds now come equipped with wi-fi connectivity built into the walls and floor, multiple Echoes, and Alexa-powered locks, light switches, and thermostats. Rather than cede this territory unquestioningly, binding ourselves to a vision of the quantified home as battleground of competing branded ecosystems, the challenge is to see design again as an exercise in critical imagination. “I hope we’ll have the courage and agency to question the ideology of domestic efficiency”, Steierhoffer told me, “and that transformations in the home will be driven by social—rather than technological or economic—considerations”.

A warm thank you to Alexis for time and thoughts. You can contemplate domestic futures of the past at Design Museum in London until 24 March – details here.