Jack Self on finance and business as design parameters

Jack Self is an architect with a practice that extends much further than traditional forms of architecture. He’s also a publisher, editor and director of the REAL foundation. In 2016, he co-curated the British Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale.

Self’s projects interrogate how people’s lives are shaped by buildings: he radically engages with neoliberal capitalism by manipulating its structures with the aim of providing better living conditions. He has made it his mandate to challenge some of the underlying principles which govern how people live in contemporary society, proposing alternate models by tinkering in the engine room of housing and architecture – the financial models which support and shape how buildings get made.

Piers Morgan

Could you describe to me what the REAL foundation is, and how your practice relates to traditional architecture?

Jack Self

The REAL foundation is a cultural institute and an architectural firm: it would be your traditional architectural firm that likes to do cultural projects except that we have adopted a voluntary structure of a foundation. We are a limited company, but the foundation model means that we have a board of advisers, and a binding mission statement. In our case that means that we can only pursue certain types of projects, those that advance our core aims: the promotion of inclusivity, of democracy – this has become more urgent recently than we had thought when we founded the REAL foundation – and the promotion of equalities of many kinds, including gender, race, class, wealth and space. In that sense, we are forcing ourselves not to suffer from mission creep. We started working as REAL from the end of 2015, just before we applied for the British Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale, our first project. Which was, I guess, an unusual project for a practice to have as its debut.

PMYes, is that unprecedented for the Venice Biennale? At least for the British [Pavilion]?

JSI think it was. For the British Pavilion, our project was called Home Economics. It was about new models of domestic life, and it basically suggested that if you want to campaign or push for a more just and equal society, then a very good place to look at is how the home is designed in terms of its power relationships and its economic relationships. How it’s financed, how we look at housing crises, how we look at furnishing or interior decorating, how all these elements are united in a kind of, let’s say, social project.

The other project that we launched simultaneously was our cultural magazine, Real Review. We have published about half a dozen books, including, most recently, a book about Mies van der Rohe’s only UK project [Mansion House Square], called Mies in London. We run Real Review in partnership with a design studio [OK-RM], and it has expanded to the point where it’s almost a separate entity within the practice. However, in the last four or five months, we are pivoting more to doing design and built work.

PM I also wanted to ask you about the adjunct to architectural projects that the REAL foundation proposes, the financial products.

JS We believe that form follows finance, and that part of having more control over the built environment, and part of building better architecture, is having more control over the way that buildings are financed.

With a traditional developer or housebuilder, a project is established, and the financial models are already in place way before they ask an architect to be involved. There’s not a huge amount they can do to that brief, to fundamentally alter either what the project is about or how it must be delivered, because of those financial conditions. If a developer is doing what in the UK is called PRS, private rental sector, which means you build it and you rent it out immediately, a building has to be quite durable because your financial model means that you have to have it occupied for a long period of time, as opposed to developers who are simply building to flip and sell buildings immediately. They’re less concerned with quality and more with how rapidly they can build something, because obviously that is related to how much interest they pay on the loan.

We say that finance and business models are design parameters exactly the same as innovation in energy conservation, or water reuse, or historical context, or cultural sensitivities, all of these different factors. So, increasingly, REAL self-initiates projects. We say that we don’t really have clients, we have partners. We will work with developers, with cultural institutions, with a variety of actors and agents, but we tend not to work directly or underneath them in a traditional client model because you tend to end up giving away so much agency over how the project evolves.

I’m very interested in finding new ways to explore freedom in space which can create greater forms of freedom in society. We’re always interested in models rather than singular cases. We hope that everything we do can either become a typology or example that can be easily imitated by other people.

PM Is it a model where essentially you dream up a project and then go looking for a partner? Or is it more in concert with someone who potentially wants to invest some money in a building?

JS For a number of years we’ve been looking at very long-term finance models. In Melbourne, you have the Nightingale project, which I know has become a massive success there – we’re deeply sympathetic to those types of objectives – but in essence Nightingale is an architectural innovation using existing financial models. It would be very interesting to imagine what would happen if that was integrated with, for example, shareholder or bond mechanisms, or an equity fund, for example. There are as many different financial products and models open as there are architectural solutions.

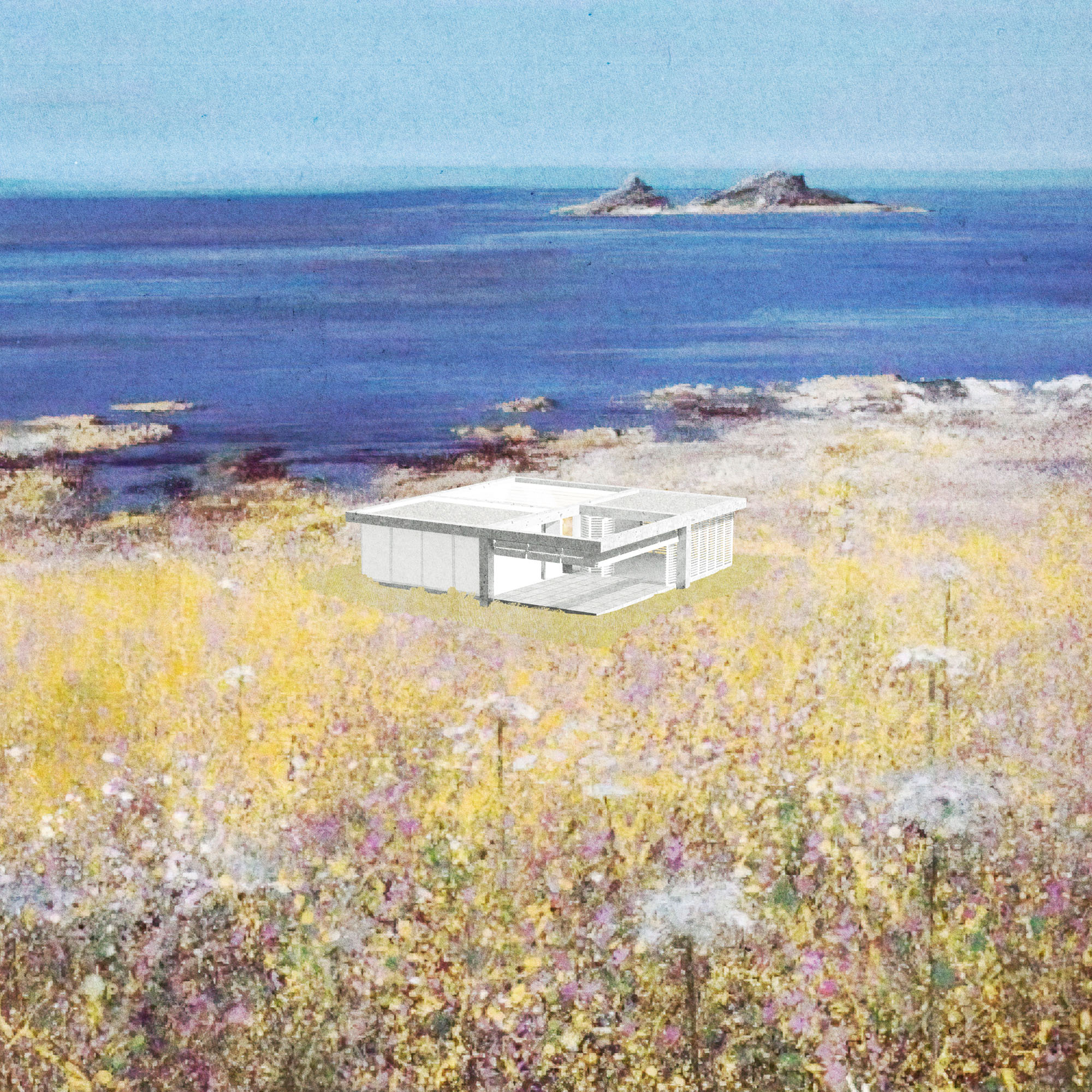

For five or six years now, we’ve been researching housing finance which is ultra-sustainable, ultra-long-term and durable, but which provides low-cost rent with the possibility to build up ownership in the building, and a reasonable rate of return to institutional investors. We’re getting quite close to establishing a model which we think will be viable. We’re working on a master plan for a housing project for an educational institution in the UK, hoping to produce a prototype for a house that’s available to buy for £35,000 (AUD$63,000), which is the average deposit on a mortgage in the UK. If that becomes successful, then REAL will hopefully start a new company solely responsible for delivering extremely low-cost houses.

JSIn designing extremely low-cost, architecturally designed kit homes, you get to explore a lot of really interesting questions about the history of functionalism, the structure of contemporary life and the family, about the future of sustainability, about what is really necessary for contemporary life.

You get to design buildings on spec without having a client in mind, and that allows you to design houses which are an ideal vision of what you think society might want to live in, rather than having to each time respond directly to the whims or specifics of any individual client. We’re really trying to design for society as a whole.

One of a couple of Australasian projects we’re involved in at the moment is a co-housing project. It’s increasingly very expensive to live in cities like Auckland, Sydney and Melbourne, Toronto, London, which have very similar property markets, impacted by capital flight and shortfall in supply, which means that you get insane overpricing in the markets. But if you move out of the city to the countryside, the only available model is the single-family home. For people used to fixed-gear bikes, flat whites and working in a design studio with like-minded people, moving to a single-family home in a rural environment can be quite isolating. We say there are ways in which we can group together, pool our resources and build – not just groups of individual houses, but a kind of commune or complex with common facilities, such as workshops and studios and other types of amenities. If we’re prepared to pool our resources, we will always have more and better quality than if we insist on building everything on our own, which only leads to redundancy and duplication.

PM What’s your philosophy on the relationship between efficiency and freedom in architecture, and in your work?

JS The shortest answer to that is that my main architectural interest is in rejecting all forms of functionalism. Buildings can serve a function and serve it well, but functionalism, as opposed to function, is all about predetermination. In order for architecture to remain useful for very long periods of time, we need to design spaces which can adapt to different forms of life.

I’m very interested in finding new ways to explore freedom in space which can create greater forms of freedom in society. We’re always interested in models rather than singular cases. We hope that everything we do can either become a typology or example that can be easily imitated by other people.

I’m not interested in creating singular artistic works, I’m interested in creating systems and multiple models which can be replicated and built on collectively, and through that copying become more robust.

PM There was a project you posted on Instagram [in August] – I’m not sure whether it was the beginning of something larger, or just a post – based on the ‘plastic number’?

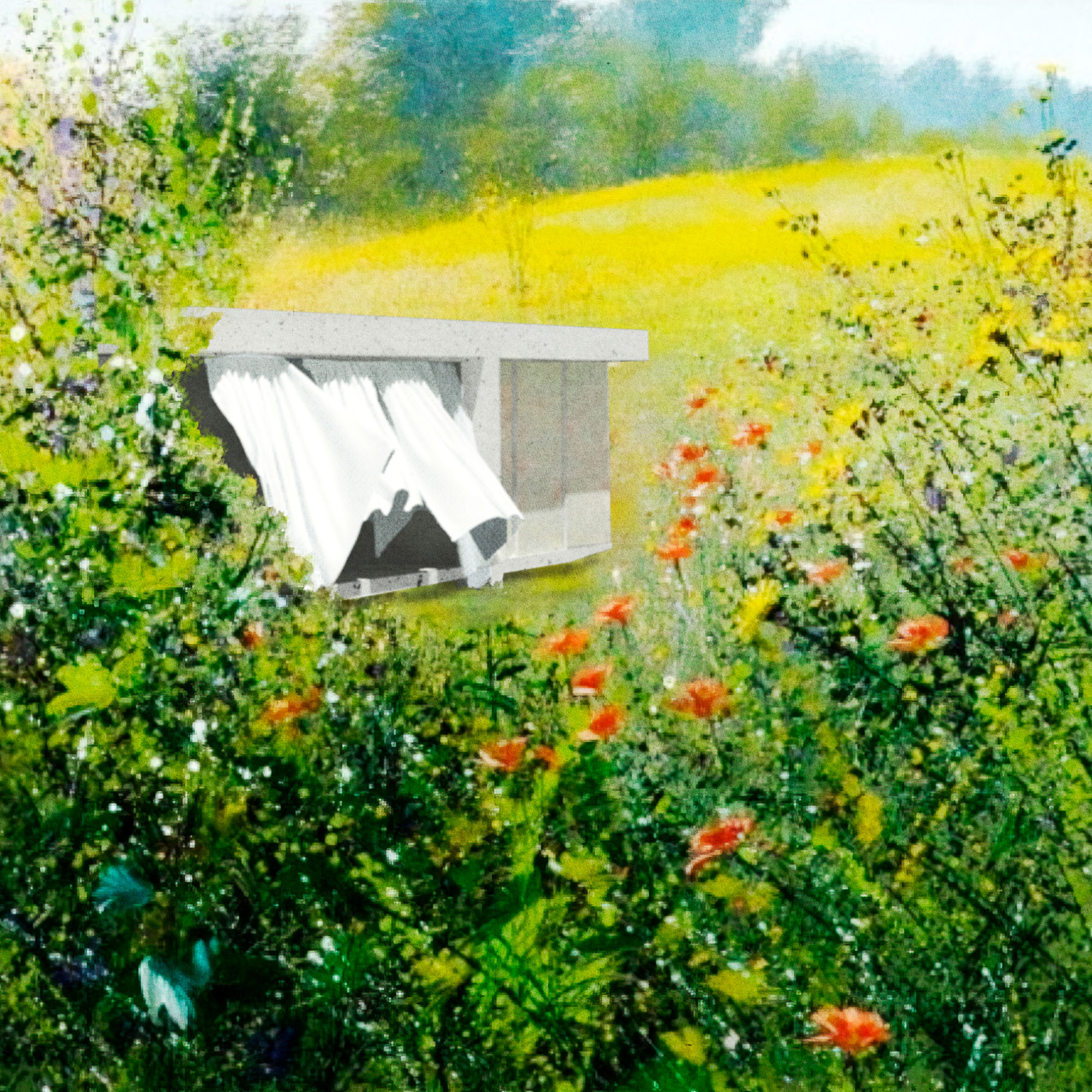

JS It was designed as an artist’s studio for a large, London-based cultural institute. They asked for a proposal for an exhibition, but I wanted to do a building.

I had the Australian condition in mind when I was designing it; Australians generally have a unique and sensitive response to what is actually needed for life, and they’re a lot less conservative than Europeans when it comes to alternative forms of life.

JSThat project is called Lux Aeterna: a building with four rooms, no function to them at all, each one pointing in a slightly different direction of the compass, with different qualities of light throughout the day, and those qualities of light will influence your experience of the space. Beyond that, I wanted to completely atomise any function in the building. The bed is a hand-cart which can be rolled around on wheels, the kitchen is basically just a Primus stove, and the bath, which is my favourite design, is filled up with a garden hose, with electric elements inside which allows you to heat the water in place. It sits on one of those pallet trolleys which are used for moving boxes around warehouses. You could have a bath in any of the rooms and you can sleep in any of the rooms. It’s up to every individual to inhabit the space as they think best.

Architects have often talked a lot about proportion and systems of proportion, but they very rarely explain how they’re actually used. We all know about Palladio and the golden mean, or Corbusier’s Modulor, but no-one designs using these modules of proportion; we’re more likely to use an arbitrary industrial standard, like the size of a panel of plywood. I’m very interested in this idea of abstract or nonhuman systems of proportions. The ‘plastic number’ was invented by a monk called Dom Hans van der Laan, who left a very good set of lecture notes that make it possible to understand how it can be used and how it can apply. I wanted to explore his idea in this building.

PM The same approach to changing qualities of light, of course, could be taken with thermal comfort – thinking, instead, of ‘thermal delight’. Spaces shouldn’t necessarily be at 20 degrees the entire cycle of the day and the year.

JS Certainly. In my master’s thesis in philosophy, I wrote a text called 20°C, which was a study of Heathrow Airport. Almost all international airports try to hit 21 degrees Centigrade as a form of biometric control. It’s the lowest temperature that the average body can drop to before it begins to feel cold. If you’re trying to get a group of people to sit still for long periods of time inside a metal tube, the best way is to lower their heart rate and lower their breathing, and lower temperature does that.

Part of what global warming means is being always thermally uncomfortable. It does concern me what will happen to social harmony as global warming gets worse – I think our species is unlikely to keep its cool. We could have substantially avoided the worst of global warming in the mid-1970s, and we missed that opportunity. It is likely that most humans will die – predominantly the poorest people who are also located in the most dangerous places for global warming. The extreme wealth polarity in global civilisation will allow a very small elite to be totally insulated from the effects of global warming. How we can live with ourselves for allowing such a thing to occur to other humans will be difficult to know.

I think it’s extremely important to have criticality, but no matter how critical you are, you must always make a proposal, otherwise, what’s the point? Honestly, how would we build any society if we didn’t believe we could make some change?

PM You seem to be, on the one hand, a realist to the point of pessimism, and yet still driven and productive and unwilling to give up against what seem to be insurmountable circumstances. I’m reminded of what Czesław Miłosz said when he was asked what he would do if the world was ending tomorrow; he said that he would plant apple trees.

JSThat’s a beautiful quote. I completely agree. I worked as a landscape architect for Jean Nouvel in France, on a project where they wanted to import 80-year-old oaks from Holland. I remember thinking, the people who planted those oaks as entrance-ways to houses knew that it takes 200 years for an oak to reach full maturity. They knew that not they, nor their children, nor anyone alive on the planet at the time would see the actual design as they had intended, this grand alley of oaks. That type of investment in the future no longer exists. People today just want to buy ready-made, pre-aged oaks, have them shipped over on a barge and have them planted in situ to give the impression of having invested in the future without the necessity of actually doing so. Now, that’s just a reflection on the apple tree quote, but I think that Carl Sagan, the 1970s awesome astronomer, is my guide on this. He says, “Approach the world with scepticism and imagination.” I am very keen on being a realist inasmuch as understanding what’s going on and not shying away from difficult discussions, be they about global warming, institutional racism, gender inequality or discrimination. These are difficult subjects to look at honestly, but hopefully we can see within that condition the possibility of making a proposition.

JSI think, at its essence, that’s what it means to be an architect. Architects are extremely optimistic people. A client will come to you; they’ve got a shitty site, no money, they’ve got planning restrictions and they say, “What can you do?” And you say, “I’m going to do the best piece of architecture you’ve ever seen. I’m going to knock it out of the park.” That kind of optimism is the essence of the project. That’s what ‘project’ means: to project a vision of something which is an improvement on what exists at the moment.

I think architects are quite unique designers: we are forced to engage with all of the ills in society, the difficulties and complexities of property and the built environment, what it means to live, and out of that we always make a coherent proposal. I don’t know whether I became an architect because I think that way, or whether my training as an architect reinforced this. I think it’s extremely important to have criticality, but no matter how critical you are, you must always make a proposal, otherwise, what’s the point? Honestly, how would we build any society if we didn’t believe we could make some change?

Many thanks to Jack and Piers for taking the time to discuss form, finance and the end of capitalism with us. You can learn more about REAL foundation on its website, or subscribe to Real Review. This interview first appeared in AP#10: Housing, get your free copy at MPavilion.