Designing club culture

In late March, the Grollo Group announced it had acquired 54-60 King St in Melbourne, the two-storey property housing Inflation nightclub, in an off-market deal. Reportedly, the Grollo family saw the site as the elusive final piece of its ‘Rialto precinct’ puzzle—transforming the notorious late-night strip at the western end of the CBD into the sanitized hub of a rebranded ‘midtown’. How things change. When Inflation first opened its doors, in 1979, it was at the vanguard of a heady new era in Melbourne’s nightlife. Inspired by fabled clubs like Studio 54, which had launched in New York two years earlier, owner Sam Frantzeskos was a disco pioneer in a city then defined by the parochial Oz rock ringing out from sweaty suburban beer barns, and a post-punk and new wave scene beginning to take shape around inner-city venues like St Kilda’s Crystal Ballroom.

Inflation didn’t just channel the foreign glitter and decadence of a rising disco culture. It was Melbourne’s first real example of a modern entertainment archetype—the nightclub. By 1979, Victoria was barely a decade removed from the buttoned-up days of the ‘six o’clock swill’. Even with the repeal of early closing laws in 1966, after dark options were limited. The city’s original discothèques, inspired by the swinging 60s clubs of London and Paris, were unlicensed and all-ages. Counterculture blow-outs, like the monthly Reefer Cabaret at Ormond Hall, periodically lit up church and community halls around the inner suburbs before vanishing again. In the early 1970s, pubs like Prahran’s Station Hotel began to book regular gigs as part of an expanding live circuit, but it was another few years before the ritualized gender segregation that relegated women to the ‘ladies’ lounge’ began to break down.

Echoing the earlier viral spread of rock and roll, Melbourne’s embrace of dancefloor hedonism didn’t happen in isolation. The dawn of a local club culture followed in the slipstream of leading international scenes. These stories, from New York to Berlin, take center stage in a new exhibition at the Vitra Design Museum outside Basel, curated by Jochen Eisenbrand, Catherine Rossi, and Katarina Serulus. Night Fever: Designing Club Culture 1960—Today is the first show of its kind to explore the emergence of nightclubs as unique spaces for experimentation with interior design, new media, and alternative lifestyles. What resonates above all, though, is how fundamentally nightlife shapes wider urban life. From economics, to politics, to planning, the nocturnal spaces and habits of a city reflect the unspoken desires brewing below the surface of daytime routine, as well as anticipate broader societal shifts to come.

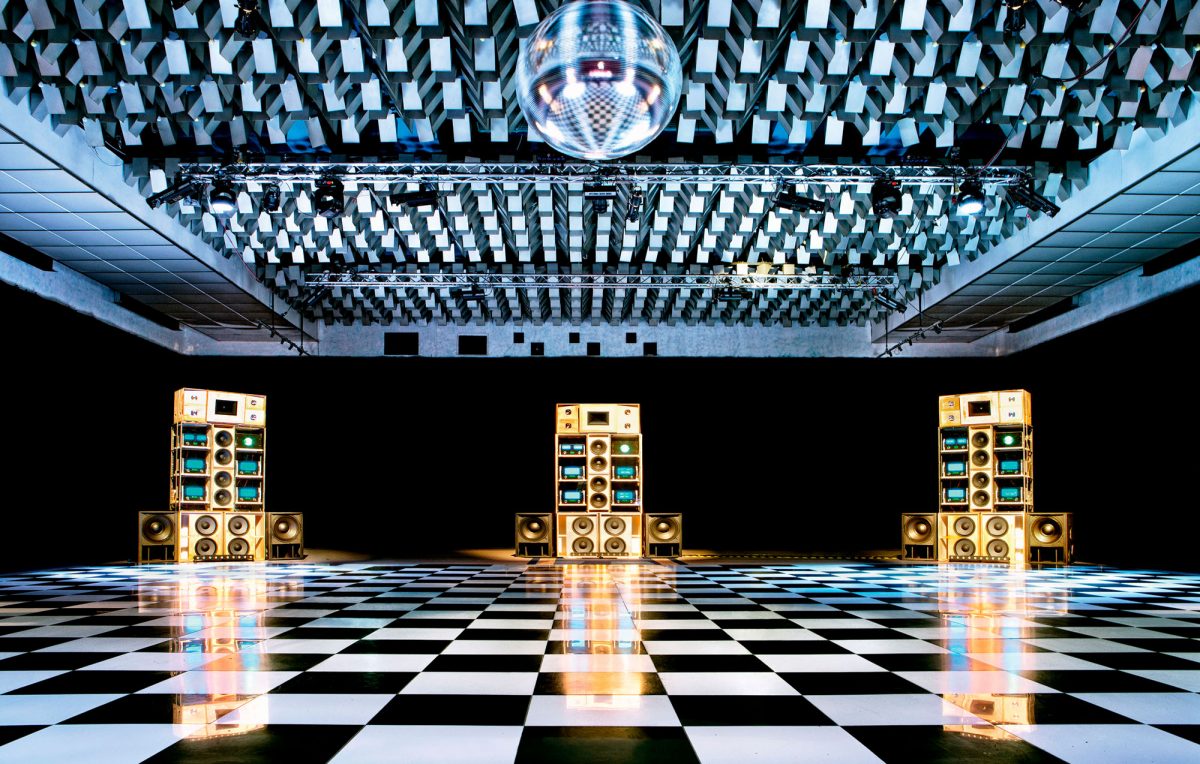

Eisenbrand, Rossi, and Serulus hint at this relationship in their opening curatorial statement: “Clubs belong to the city. A vital club culture emerges where the urban fabric offers ample freedom”. The exhibition itself is arranged chronologically around four halls. The first, ‘Beginning to See the Light’, focuses on the psychedelic sensory experience and early spatial experimentation of the northern Italian discos that emerged out of the 1960s ‘Radical Design’ movement. The second, ‘Can You Feel It?’, is a standalone installation by Konstantin Grcic and lighting designer Matthias Singer, which captures the stylistic evolution of the music that set dance floors in motion. Cocooned inside a pulsating neon grid, with mirrored panels stretching to infinity, suspended headphones guide you through the decades, as the loose rhythms of funk and soul morph into the mechanized thump of disco, house, and techno.

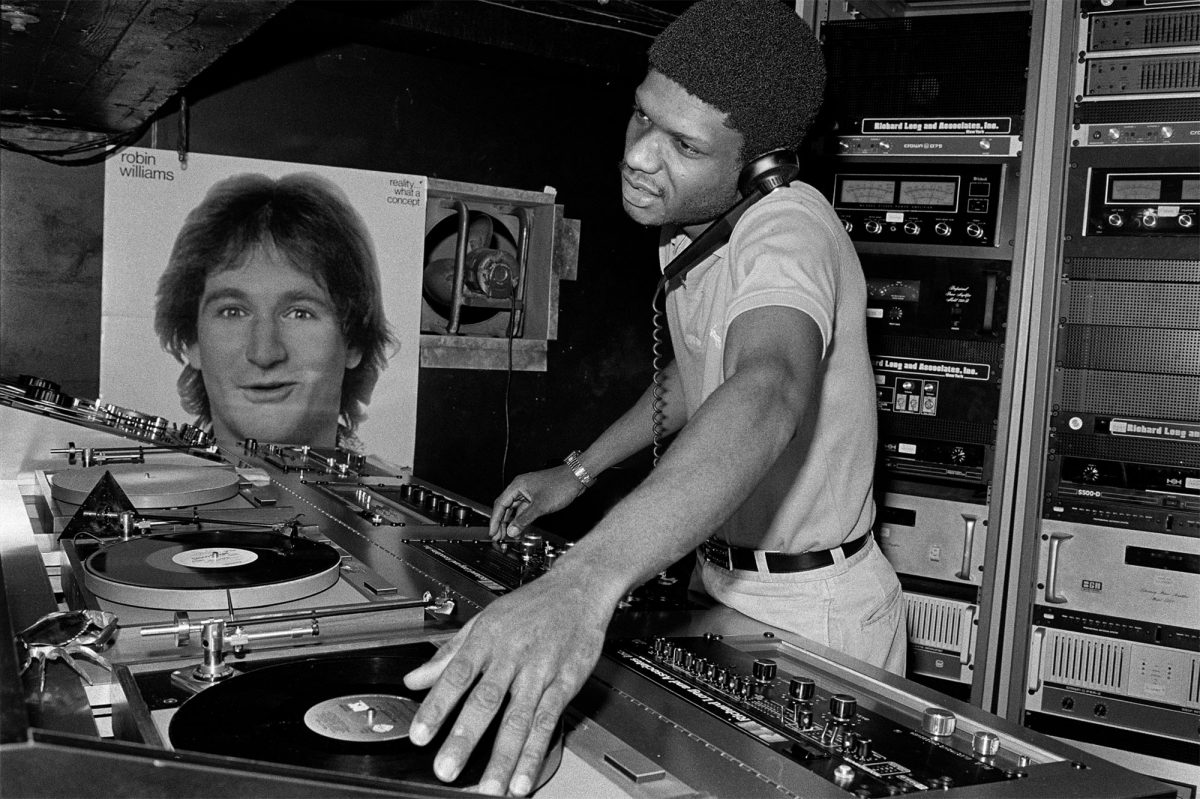

By the third hall, ‘Slave to the Rhythm’, night fever has taken hold. The see-and-be-seen celebrity excess of Studio 54 shaped the zeitgeist—along with a strutting John Travolta. But the New York after-hours loft scene that originally inspired its founders also spawned seminal downtown venues like the Paradise Garage, which did far more to influence the future direction of dance music, through DJs like Larry Levan, as well as its cross-pollination with the worlds of art and fashion. Across the Atlantic, the Haçienda, in Manchester, was similarly ahead of its time. Designed by architect Ben Kelly, the space prefigured the rise of a post-industrial aesthetic that would later find its spiritual home in the derelict bunker clubs of post-wall Berlin. And though bankrolled by New Order and Factory Records as—initially—a live music venue, the introduction of club nights in 1986, combined with the arrival of ecstasy via Ibiza a year later, would see the Haçienda become ground zero of the acid house revolution.

If Inflation ushered in a new era in Melbourne clubbing, the launch of the Metro in November 1987 seemed like a victory lap for Frantzeskos. The opening of the first ‘superclub’ at the top of Bourke St was even broadcast live in a Channel 10 special hosted by Molly Meldrum. But Britain’s ‘Second Summer of Love’ was about to see rave culture land on Australian shores, while John Nieuwenhuysen’s review of the 1968 Liquor Control Act was about to fundamentally transform the possibilities of nightlife venues in Victoria. Within a few years, a fresh generation of clubs had begun to emerge across the city, fueled by reforms to liquor licensing laws, an early-adopter gay scene alert to the house and techno spinning out of Detroit and Chicago, and a more permissive approach to the CBD’s developing nighttime economy. At the same time, Melbourne’s current property bubble had yet to lay claim to countless idle buildings that proved to be a perfect fit for the new wave of DIY warehouse parties.

Speaking to me from the Vitra Campus in Weil am Rhein, I asked Jochen Eisenbrand what, if anything, he saw as connecting the diverse movements presented in Night Fever. “The club scenes in certain cities were often particularly interesting when those cities were at a turning point”, he replied. “The transition from the industrial city to the post-industrial city seems to have been a key moment.” This certainly rings true for Melbourne. Relaxed licensing laws were important—especially when further changes under the Kennett government in 1994 allowed alcohol to be sold without food service, kickstarting the small bar boom. But this was also occurring against the backdrop of the property market crash of the late 1980s, which left large swathes of commercial space in the CBD and inner suburbs vacant or under-utilized. Pioneering promoters capitalized on these opportunities, leading to iconic venues like the short-lived Global Village complex in Footscray.

The final hall in the exhibition is named ‘Around the World’. But what may seem to celebrate the moment club culture went global plays more like a requiem than a climax. Though bleary‑eyed Monday morning easyJet flights out of Berlin Tegel attest to the continuing pull of weekend warrior club tourism, Martin Eberle’s elegiac photographic series, ‘Temporary Spaces’, documents a fluid post-unification scene that has largely disappeared. While new nightlife cultures are emerging in cities like Shenzhen, global brands that rode the early-90s underground wave to commercial dominance, like the Ministry of Sound, are now pivoting to co-working spaces and fitness classes (Ben Kelly too, has channeled the Haçienda aesthetic in a chain of boutique London gyms). And club closures are rife in many cities, squeezed by the twin pressures of gentrification—rising rents and noise complaints—not to mention the disruptive cultural impact of dating apps.

However, Eisenbrand emphasized, a “growing awareness of the importance of nightlife for urban economies” is starting to counterbalance the losses. In 2016, it was estimated that New York’s $13 billion nightlife industry supported 100,000 jobs. In London, the after-hours economy is thought to generate more than $46 billion each year. Both cities (alongside Paris, Zürich, Berlin, and others) have recently followed the lead of Amsterdam, which established the position of ‘night mayor’ in 2014. This non-executive office holder advocates for nocturnal businesses, liaises with residents, law enforcement, and city officials around governance and regulation, and champions a diverse nightlife culture. Beyond naked economic calculation, these moves represent a deeper recognition in numerous capitals of the extent to which the scenes documented in Night Fever act as incubators for broader trends in pop culture, and experimentation within the creative industries.

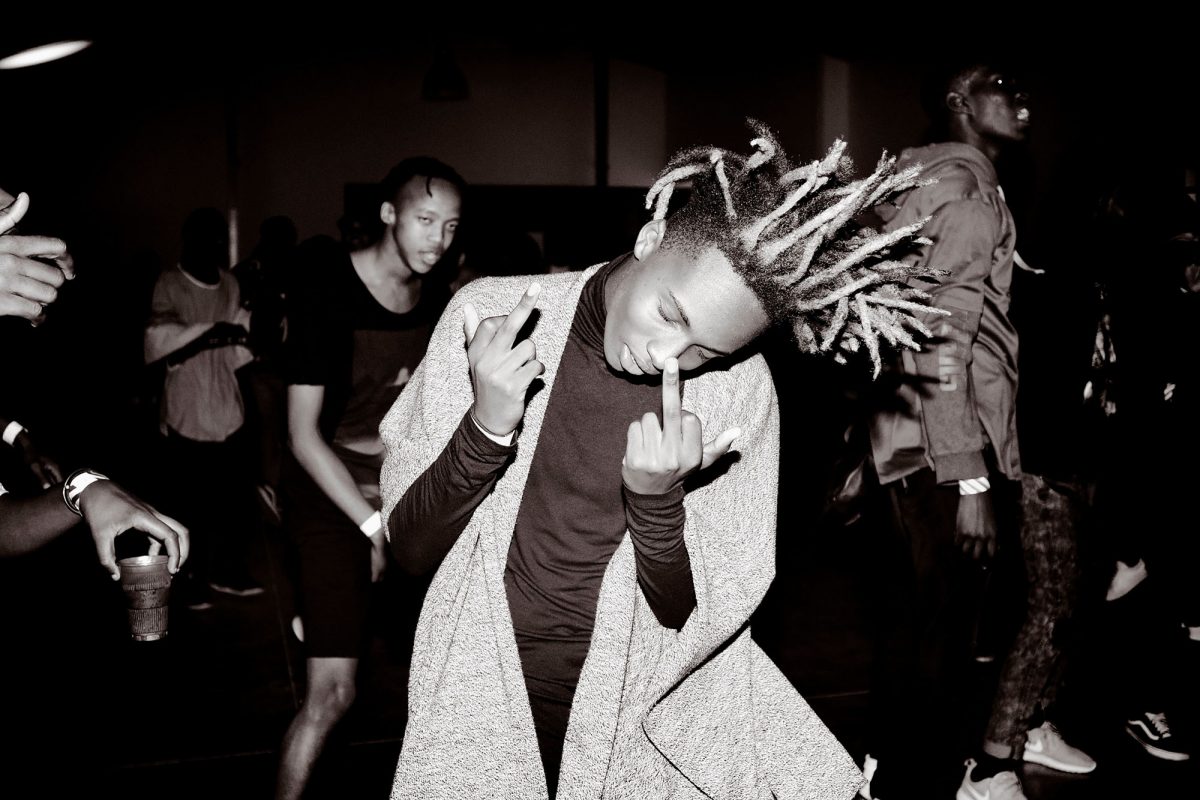

According to recent figures, the number of (known) illegal raves in London doubled between 2016 and 2017. Despite fears that millennials have taken up permanent residence online, appetite for the IRL clubbing experience remains. Yet London is also a cautionary tale of how gentrification and escalating living costs can pour water on a thriving scene. When it looks to the future, rather than the fever dreams of the past, Night Fever is primarily concerned with new forms of mobile architecture and ephemeral gatherings. But this glosses over the link between club culture and urbanity. Unlike Sydney and its continuing lock-out debacle, Melbourne has learnt from its past and is moving in fits and starts towards becoming a truly 24-hour city. But as the engine of speculative development continues to remake that city, the diversity of spaces vital to a thriving local scene must remain accessible to the next generation of nightlife entrepreneurs.

A huge thanks to Alexis for this critical review of nightclubbing design in Melbourne and globally. The exhibition ‘Night Fever. Designing Club Culture 1960-today’ runs at Vitra Design Museum in Weil am Rhein until 9 September 2018: more details here.