Kids’ City puts children first in Copenhagen

In the 1960s, the Danish capital Copenhagen made the decision to reject the modernist car-centric planning policies of the time and champion citizen-centric design. It was a resolve that has earned it multiple titles of the most liveable city and seen the inception of the verb ‘Copenhagenize’ in reference to elements of its coveted urban model.

It is no wonder then that, when approaching the design of Kids’ City kindergarten and – previously – Frederiksvej Kindergarten and Forfatterhuset Kindergarten, Copenhagen-based practice COBE adapted this notion of human-centric design, and designed a facility inspired by kids’ perspective on the world.

“The starting point for [Kids’ City] was to create a building from the view of a child,” says Dan Stubbergaard, founder and creative director of COBE. “The result is a scaled-down environment of many different worlds, but also a place where kids can feel a sense of belonging to one specific house within the cluster of houses.”

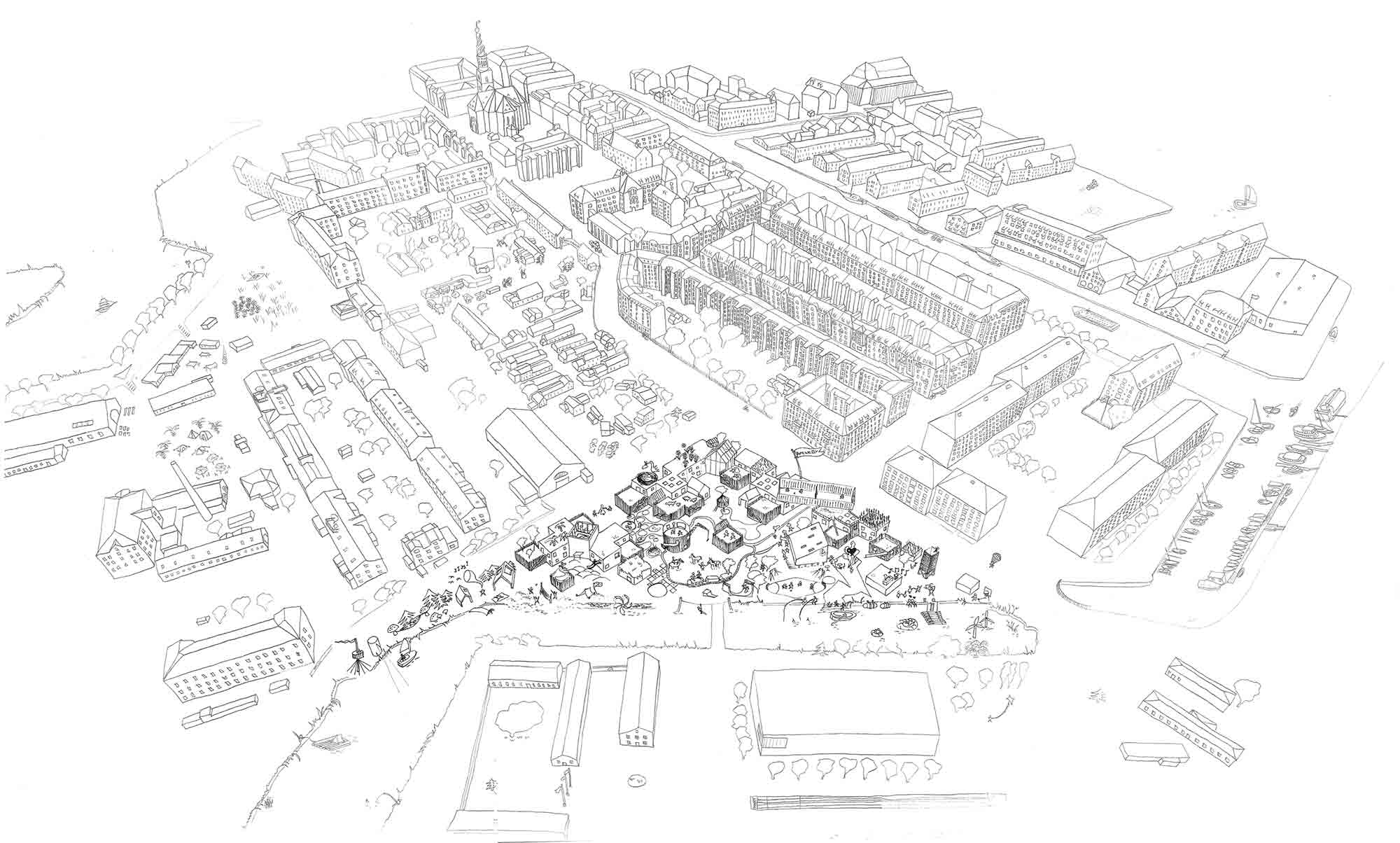

The population of Copenhagen is set to increase by an additional 90,000 residents by 2025, inclusive of 22,000 children between the ages of 0–18 years. In addition to progressive governmental policies surrounding parental leave and the provision of heavily subsidised child care, there has also been a priority in funding for the provision of spaces and facilities for children and families within the urban centre of Copenhagen. As a result, the city has become a practicable space for families to live in. Kids’ City is one of these new facilities, a childcare centre in the central Copenhagen neighbourhood of Christianshavn. COBE, in collaboration with NORD Architects, won the design competition for the childcare centre in 2012. Upon full completion in late 2017, it became the largest day-care centre in Denmark.

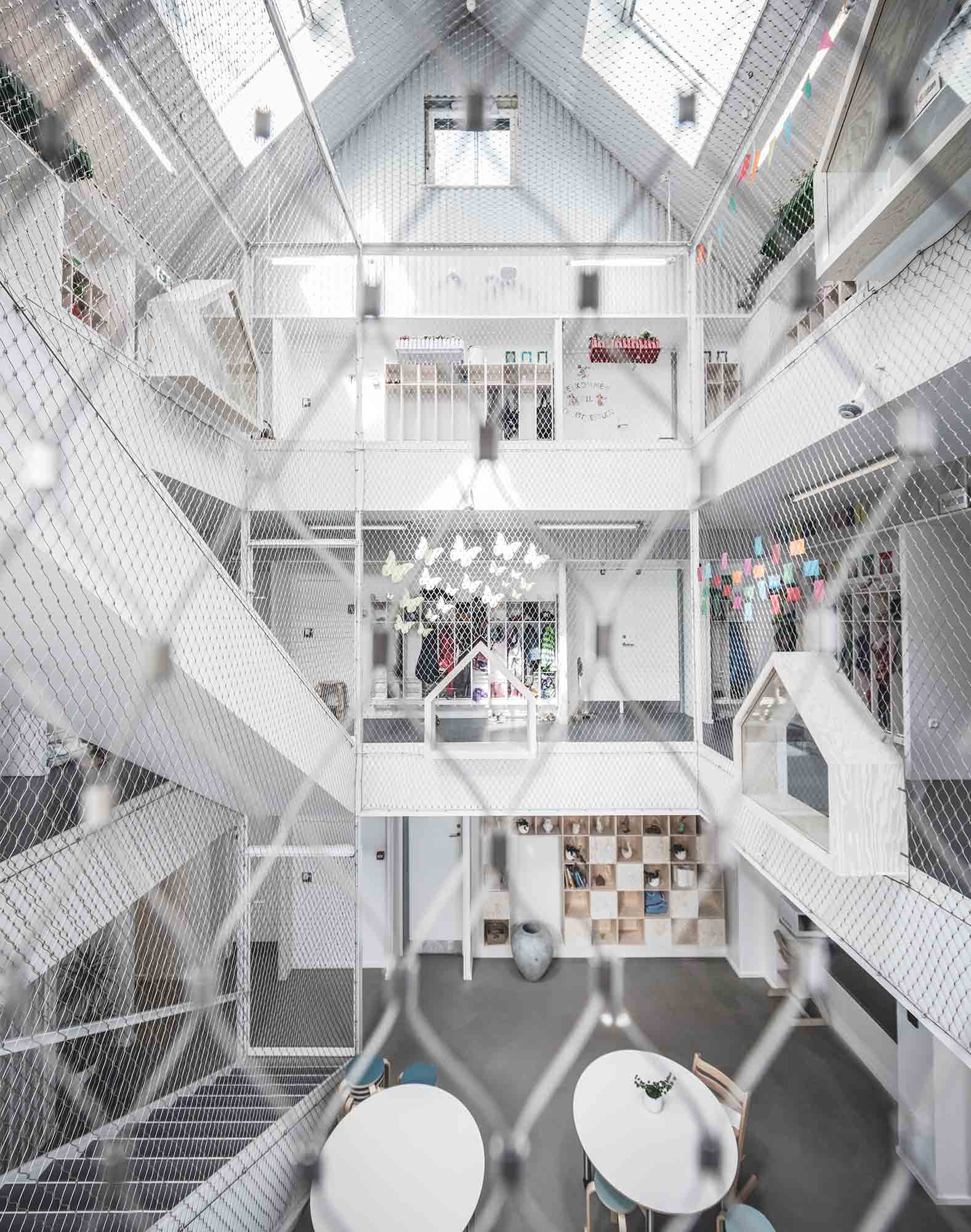

Kids’ City is made up of several existing day-care facilities for children of different ages, with the capacity to accommodate 710 children. Unlike a generic day-care facility, the approach and design had to consider not only the accommodation of a large number of children, but also a diversity of ages and needs. “This facility is designed to be a small city for kids, rather than one big building,” says Stubbergaard. “Like Copenhagen, this new city has different neighbourhoods, houses, public spaces, squares and parks. It even has a city hall, a fire station, a restaurant, a stadium, a library, a museum and a factory.”

Christianshavn is a neighbourhood with a unique demographic. The surrounding area is inclusive of Christiania Freetown, a self-proclaimed autonomous anarchist district. Conversely, the area along the Christianshavn Canal is the location of some of the most expensive apartments in Copenhagen. In addition to designing for the diversity of the surrounding community, the architects had to address the mix of ages, with children ranging from 0–15 years: infants, pre-school children and schoolchildren, as well as young people. “Spaces vary in both scale and contents, with both small, secure and intimate spaces, as well as big and challenging areas,” says Stubbergaard.

“As the children grow, they will move between the different neighbourhoods in the day-care facility, and the transitions should never be monotonous or stressful.

“The idea is that the physical and visual contact between the different age groups will strengthen the overall sense of community by smoothing the transitions between the ‘neighbourhoods’ in the ‘city’.”

COBE’s practice is grounded in notions of urban democracy and social liveability, with an attentiveness to scale – both architectural and social. Theirs is an inclusive architecture: social, practical, whereby economic and environmental issues are integrated, and adaptability to the local context and its social life is prized above beauty of form. The firm’s approach is to “consider architecture to be a process of dialogue,” involving experts and users in every stage of design.

Community engagement and consultation was key in the development of Kids’ City. After the competition, during the early stages of detailed design, a user group was assembled, made up of representatives of management from these day-care facilities, as well as parents. COBE and NORD Architects presented many different schemes to the user group and “in the end, we came up with a design that satisfied the users, the municipality and us.”

With the proudly championed egalitarianism of Danish society and the subsequent cultural expectation of both parents to work, childcare policies are held in high importance within Danish politics. “Parents want their children to grow up under the very best conditions,” says Stubbergaard. “That is a basic human instinct. Thus, guaranteed day care, bigger institutions, and higher efficiency have been put on the political agenda to address the growing pressure on our kindergartens, making the city attractive for young parents living in the city.”

Childcare is heavily subsidised by the government. Denmark has one of the most progressive paid parental leave schemes in the world, over 52 weeks: four weeks prior to a childbirth, 14 weeks post-childbirth for the primary caregiver and two weeks post-childbirth for the secondary caregiver, with a further 32 weeks split optionally between the two partners. This was not always the case, though.

“The first kindergartens in Denmark opened in 1924 and served as asylums for children from poor working-class families, where both parents worked – or single or widowed women, who had to work to support their children,” says Stubbergaard. “These families could now keep their children off the streets and out of the factories.” The situation changed when women entered the labour market in large numbers during the 1960s: “The need for kindergartens became urgent.”

Today, 67.9 percent of children in Denmark aged 0–2 years old attend some form of childcare. “Some of the children attending the Kids’ City will possibly spend most of their daily life at the institution, from their earliest days until they are 18,” says Stubbergaard. The approach to the design, therefore, had to comprehensively consider the developmental needs of children at all ages. “The design of the facility is developed to protect the youngest citizens of Kids’ City, locating them far away from the [canal] and shielding them from the surrounding city traffic. In order to make daily life for the kids safe and inclusive, the architecture and outdoor spaces are made to ‘grow’ with the children.”

The provision of spaces and facilities within the urban area of Copenhagen that are specifically designed for children and families has seen the city experience a substantial increase in the quality of living. Counter to the urban sprawl that envelops most Australian cities as families move away from city centres, staying within the urban centre is a much more viable and approachable option for families in Copenhagen. However, it was not always so: backing up these design successes is progressive policy and planning developed since the 1960s.

“In the previous century, the dense city was associated with unhealthy and poor living conditions,” says Stubbergaard. “Families did not choose to live in the city; it was a necessity, determined by the central location of factories and workplaces. During the post-war 1950s and ’60s, close to half of the population of Copenhagen gradually left the worn-down city centre for the idealised life in the suburbs. They were seeking modern housing, more space, and a healthier environment for kids to grow up in.” It’s a statement that echoes the current concerns and conversations in relation to perceptions of city versus suburban living in Australia.

“Today, the suburbanisation trend has reversed. Due to a comprehensive transformation in Copenhagen, we are now seeing a renewed densification of the city centre,” says Stubbergaard. The transformation has been the result of a turn toward human-centric design, the development and design of spaces at a human scale, and the importance of government and municipality support for projects such as Kids’ City. “Many young families that would have once moved away are now choosing to stay. The successful urban transformation has turned Copenhagen back into a city for families and children,” says Stubbergaard.

He adds: “Children represent the future success of any urban environment, and are the most valuable resource in our community. In the past decade, the Danish government has recognised this and funded a wave of exciting initiatives, including more playgrounds, child-friendly parks and urban squares, and streets that are safe to play in.”

Designed with the prioritisation of children and families in mind, places like Copenhagen’s Kids’ City are an exemplar of how far progressive ideas can go in the realm of design. For, once the governmental support is in place, it is then the role of architects to provide the appropriate spaces, armed with an understanding of the importance of creating innovative and engaging environments.

“With children spending most of their waking hours at schools and other institutions, architects play an important role in creating the best possible surroundings for them to grow up in,” says Stubbergaard. “Surroundings that encourage learning and creativity, and that support the individual child whilst also celebrating the community.”

This article originally appeared in Issue 9 of Assemble Papers ‘Radical Family’. Thank you to Janie for your words, and to Dan Stubbergaard for sharing his incredible knowledge of Kids’ City and the philosophies behind it. Dan is the founder and director of COBE.