Finding an intentional community in Sydney’s Planet X

The Planet X housing co-op in Sydney’s Chippendale area gives members of the LGBTIQA+ community more than just stable housing. Anita Delle-Vergini speaks with Chris Ryan and Holly Zwalf about the life-changing potential of co-op living.

Creating a home with like-minded people is a common motive behind choosing co-operative living: establishing a strong sense of community builds meaningful relationships, improves quality of life and can provide a platform for support and opportunity. This particularly holds true for groups subject to social, political and cultural struggles.

For Holly Zwalf, the community aspect of co-op living has been fundamental in helping realise her professional and personal goals. Zwalf is a solo parent by choice, a decision greatly facilitated by Planet X – a small housing co-op in Sydney’s Chippendale – where she has lived for five years with her young child and a group of people from Sydney’s LGBTIQA+ community. “There’s a sense of it being our space. We want to nurture the way we live,” she says. So, what exactly makes Zwalf’s home so special? What is a co-operative housing model, and how does it work?

Planet X first met in the late 1980s with a vision of starting a housing co-op: the group was dissatisfied with the private housing market and its inability to meet their living needs. After almost 10 years of searching, it took up occupancy of a building in Chippendale after former public housing was allocated to the co-operative sector. This was made possible with support from the Association for the Resourcing of Co-operative Housing (ARCH) – the predecessor of Common Equity Housing NSW (CENSW) – a not-for-profit community housing provider that works closely with Housing NSW. All properties in the NSW co-operative program are either leased to or owned by CENSW and the overall responsibility for the housing properties is a shared arrangement between CENSW and the co-operatives.

The concept set out to provide accommodation for single people with low or varied income in the LGBTIQA+ community; a long-term home, rather than temporary housing. “In inner-city Sydney, share-housing is very unstable,” Zwalf notes. “The co-op helps people who don’t have the stability of a relationship, but who want to live centrally and be connected to the wider queer community and services, primarily based in Newtown.” Though the co-op membership is ‘single’, residents may still be involved in any relationship they choose, understood as ‘additional occupancy.’

Founding members of the co-op engaged in early community consultation to determine the types of living spaces needed for individuals within this group, which informed design of the buildings and arrangement of common areas. The Chippendale building comprises 12 single-person dwellings – a mix of one-bedroom, studio and loft apartments. In 2002, Planet X expanded to include two three-bedroom houses in Marrickville. In response to the changing needs of residents, these homes now accommodate two families or ‘living groups’ – a term used instead of ‘families’. “We recognise in queer communities that ‘family’ has a different meaning,” Zwalf says. “It’s a more elastic term.”

Though these homes are not geographically communal, they equally form part of the co-op, with a committee board member representing each home. The outside courtyard at Chippendale, originally built as a carpark, is now mostly used as a social space. It’s an open undercover area, making it a great spot to enjoy a drink, or host a birthday party or group barbecue. Occasionally, residents will invite friends to a film screening or a clothes swap in the space. Each year residents host a ‘Day of the Dead’ celebration – there’s a little party with music to mark the occasion.

Other shared spaces include a laundry, a clothesline, a storage room, a library, a bathroom with a bathtub (apartments only have showers) and an office space. The office is sometimes used by other like-minded community groups for a small donation, including sex work advocacy groups and refugee rights communities. Another group that regularly uses this space is trying to start their own housing co-op for transgender people. Over time, Planet X has provided mentorship, support and business advice to help get their initiative off the ground; CENSW is now working with them to find a property.

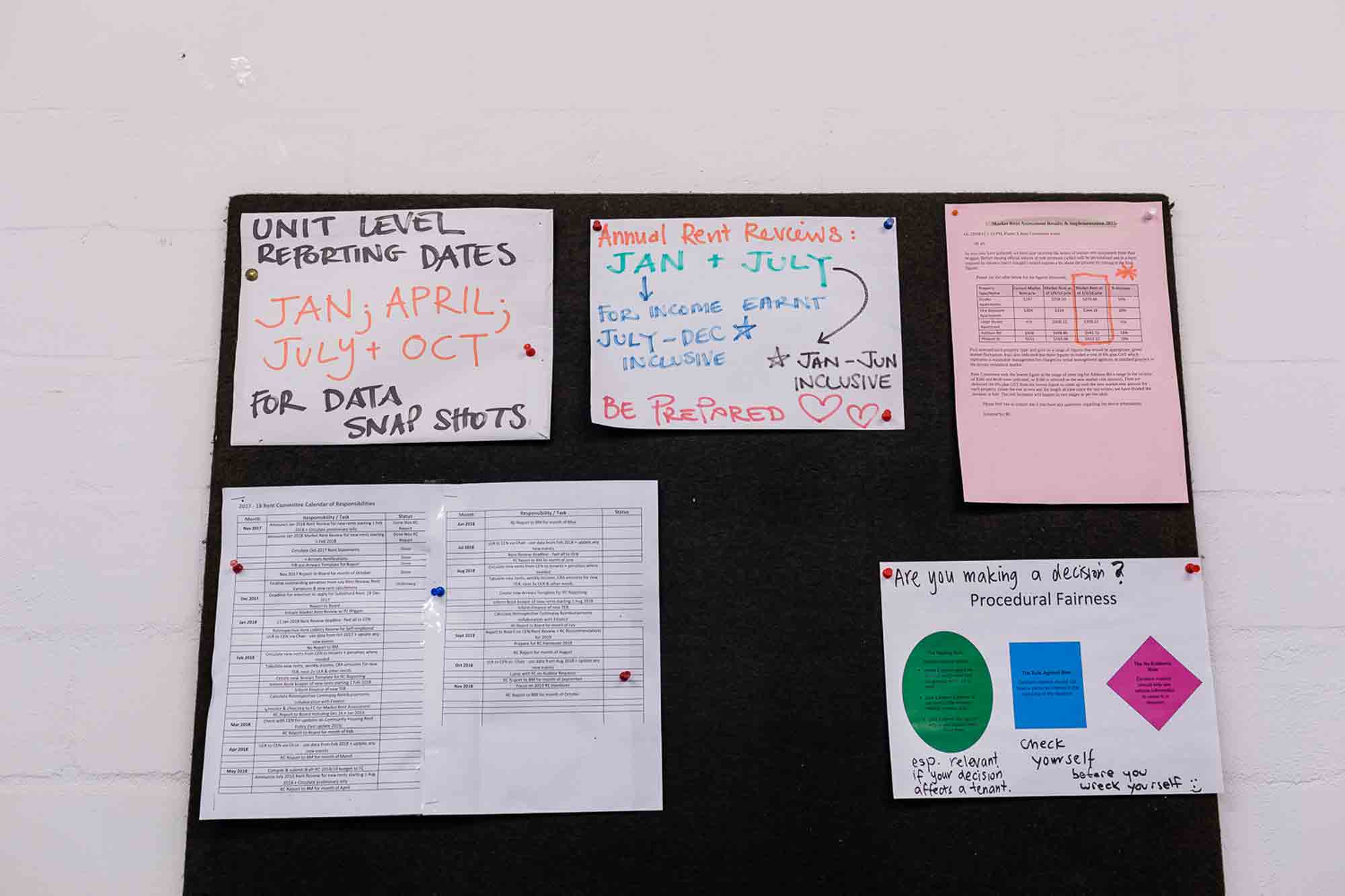

There are currently 14 members of the co-op, each responsible for ongoing committee roles. Responsibility is divided across important areas: finance, rent, office space, common areas, external affairs, training, conflict resolution, tenancy applications and onboarding, plus an elected chair each year – a role that carries the largest commitment. Members’ professional backgrounds usually inform which committee they’re best suited to – those with law and finance backgrounds are very useful when it comes to reporting to government bodies or reviewing policies. The commitment for each role will always vary depending on time of year, nature of the role and other external factors – which is one reason for the rotating system. Another reason is to ensure knowledge capital is not held by just one person. “The co-op is a shared equity of work in how we run the place,” says Chris Ryan, a current resident at Planet X, who moved in circa 2000 and presently looks after rent and office management.

Monthly board meetings are usually more agenda-driven rather than social, but topics and ideas often arise organically. “One of the hardest things about being in a co-op like ours is that you are a tenant as well as a co-op committee member and your [own] landlord,” Zwalf says. “If you have an issue, it’s your neighbour you have to deal with. There’s no external body to immediately turn to.” Ryan adds: “Sometimes people can be challenged in terms of what hat they have on. Are we speaking from a tenant or committee perspective?” The process for dealing with conflicts usually involves referral to an official policy document – one of Planet X’s living, adaptable documents – where interpretation of the policy will drive the resolution.

Recently, the group decided they needed some upskilling to assist with conflict resolution, and engaged a specialist independent group for some workshop training. “We try to hire groups with similar ideas and values to us,” Zwalf mentions. The scope for both collective and individual development through training is encouraged and supported by an ongoing training budget – either formal teaching or mentorship within the group. Skills need to remain complementary for the co-op to be utilising its potential and, when seeking new tenants, there’s an awareness of what knowledge gaps may become present.

The co-op also seeks to prioritise women, people of colour and non-binary or transgender people when looking for new tenants. These groups rely on secure housing within supportive neighbourhoods – which is often not as accessible as it should be. Planet X endeavours to have at least 65 percent of tenants meet the income eligibility requirements for public housing, as determined by Housing NSW. Rent is calculated at 25 percent of tenant’s gross income (up to a maximum equivalent to local market rent). The remaining 35 percent with higher incomes is needed to keep a balance and make it viable for those paying minimum rent. The housing model seeks to provide both security and support to residents while they study or gain experience in their chosen field, reducing the risk of sudden changes to their financial situation. A shift to higher income doesn’t mean one no longer qualifies as a resident. A career advancement usually involves upskill or specialisation, meaning one can also give back more to the co-op through mentorship or specialised advice.

Planet X is actively engaged with outside groups, and members sit on a number of external boards, allowing new ideas and thoughts to constantly spark discussion. The co-op has recently engaged with the University of New South Wales Sydney (UNSW) on research into the potential benefits and costs of solar power for apartments. They are currently working towards a proposal to CENSW for implementation of the next steps. But residents also have their separate lives outside of the co-op. “We’re not exactly living in each others’ pockets,” Ryan laughs.

Zwalf adds another relevant point: “A common critique of co-op living is the ‘ghettoisation of communities’. I don’t think that’s a negative, in this instance. I think it’s a positive – it means you’re living with people with similar interests, that come from similar backgrounds, meaning you have more support. It makes you become a stronger person, less vulnerable.”

So why is it important for safe and secure communities to exist, and how can collective living support residents of an intentional community? “Living in a co-op is like living in a small village,” Ryan reflects. “What the co-op offers you is a sense of stability and security in your housing. As a practising artist with varied income, I had been living in many shared or single accommodations, meaning limited stability.”

For Zwalf, finding the co-op came at a critical time during her academic studies. “By that point my scholarship had run out, so I was living on the dole. I had no way of earning any income and needed to focus on my thesis – it was a godsend.” Zwalf is a writer and performance poet. Like Ryan, Planet X allowed her to focus on her creative practice by easing the financial pressure.

After she moved in, Zwalf decided she wanted to have a baby, and decided to do it on her own. Therefore, she needed to be close to amenities and to the hospital, to allow for regular treatments and check-ups. “The co-op helped me realise two really big dreams,” she says. “I finished my PhD and had a baby, all in that home.”

Co-op living is not for everyone. Yet through this practical example of social usefulness, we learn much that can be applied to our wider community. Planet X sets a precedent for building a great community, shared local amenity and a sense of belonging. Surrounded with images of nuclear families, it is important – now more than ever – to build support, share resources, and seek to bridge social, cultural and political gaps, in order to move towards a more integrated society.

“If I encountered homophobia in the outside world, I knew that I was going home to a place where if I ran into someone in the courtyard I could say, ‘Guess what happened to me today? Someone yelled “fucking dyke” on the street’, and I had someone there that would go, ‘Man, that’s bullshit’, and who would get it and who would be supportive,” Zwalf says. “I always felt more galvanised going out into the world, knowing that I lived within a strong queer community.”

Thank you, Chris and Holly, for letting us into your communal oasis. Thank you also Katie and Anita for words and photos. This article originally appears in AP#9: ‘Radical Family’ – get your copy of the print magazine from our stockists! If you, too, want to join a housing co-op, you can contact Planet X through their website.