Share Yaraicho create alternatives to single-dwelling housing in Tokyo

Share Yaraicho, designed by architects Satoko Shinohara of Spatial Design Studio and Ayano Uchimura of A Studio, arose out of a desire to create an alternative to the dominant single-dweller housing typology in Tokyo. In 2012, 50 percent of Tokyo-ites lived alone, the project responded to a perceived lack of choice and diversity in available housing options in Japan, as well as an increasing awareness of the need to be energy efficient. The benefits of building close-knit and resilient communities also became apparent in the wake of the 2011 earthquakes. “Japanese people have always lived with the risk of a big earthquake,” Shinohara explains. “The social isolation of people living alone becomes more serious in such critical situations.” While share-housing existed in Tokyo prior to Share Yaraicho, these consisted entirely of retro-fitted or renovated buildings. Completed in 2012, Share Yaraicho broke fresh ground as the first newly designed share-house in Japan.

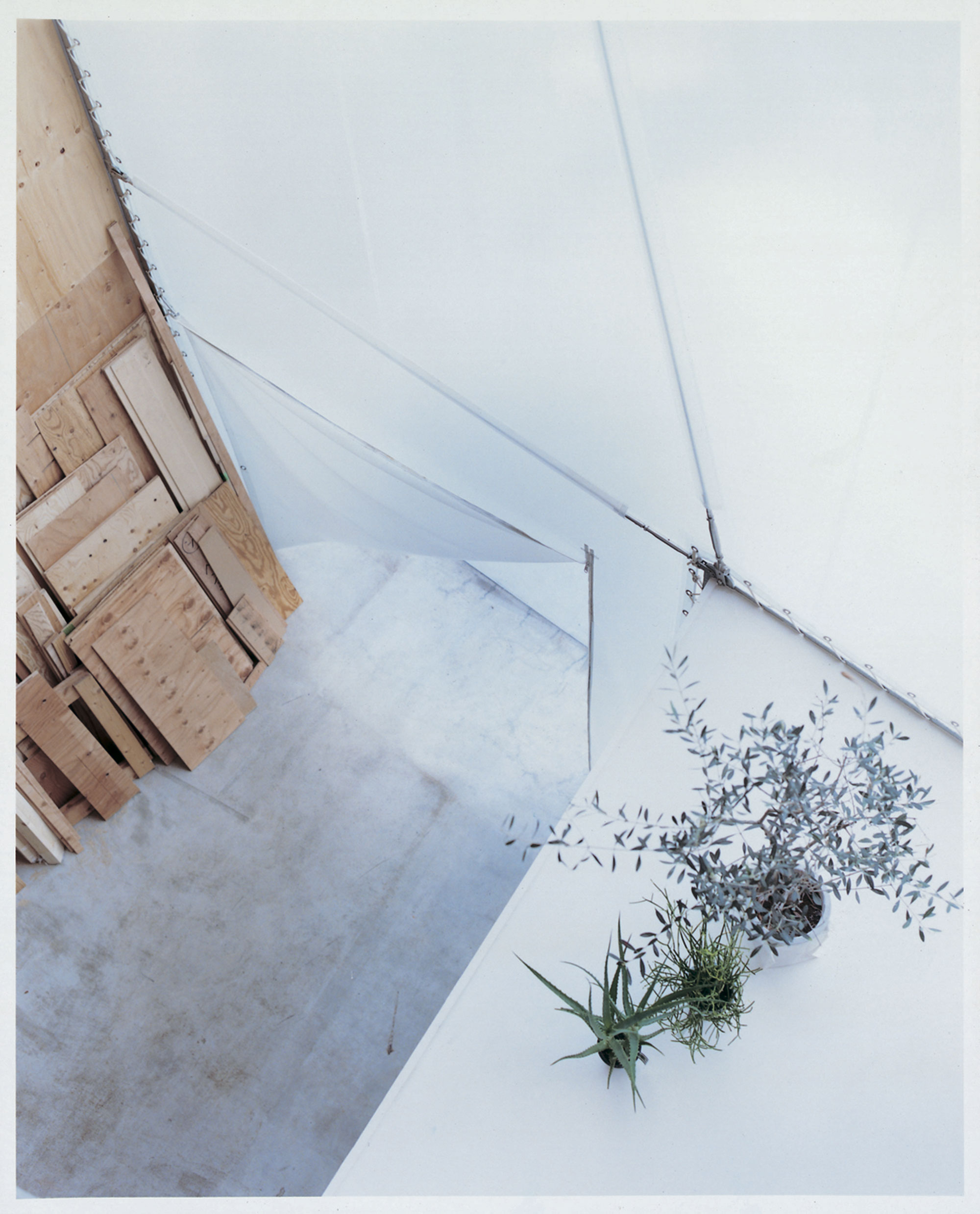

Located on a quiet, residential street in the leafy suburb of Kagurazaka, Shinjuku, the building comprises a 10-metre-high metal frame structure, encompassing seven private residential units and an array of communal spaces, clad in a waterproof, semi-transparent plastic skin. The building is close to a busy street, with access to everyday services and multiple transport options. Among the mosaic of detached houses characteristic of the downtown Tokyo area, amid the wave of large-scale condominiums and smaller subdivisions that threaten to transform the historic footprint of the local urban fabric, Share Yaraicho maintains the scale of a traditional site.

The idea of communal living and nurturing connections extends beyond Share Yaraicho’s residents themselves to the local community. At Share Yaraicho there is no door; instead, a soft plastic membrane that zips and unzips mediates the inside and outside worlds. “I think the facade and ground floor of buildings are very important because it is through these that the buildings come into contact with the outside, neighbours and society,” Shinohara says. Step through the membrane and enter the building’s entrance hall – an airy 10-metre-high transition zone that operates as an accessible space to both “invite and unite” neighbours and friends. Functioning as a flexible event space and activity venue for both Share Yaraicho residents and the surrounding neighbourhood, the hall has hosted everything from local bi-monthly urban design talks by residents to Halloween parties for the wider community.

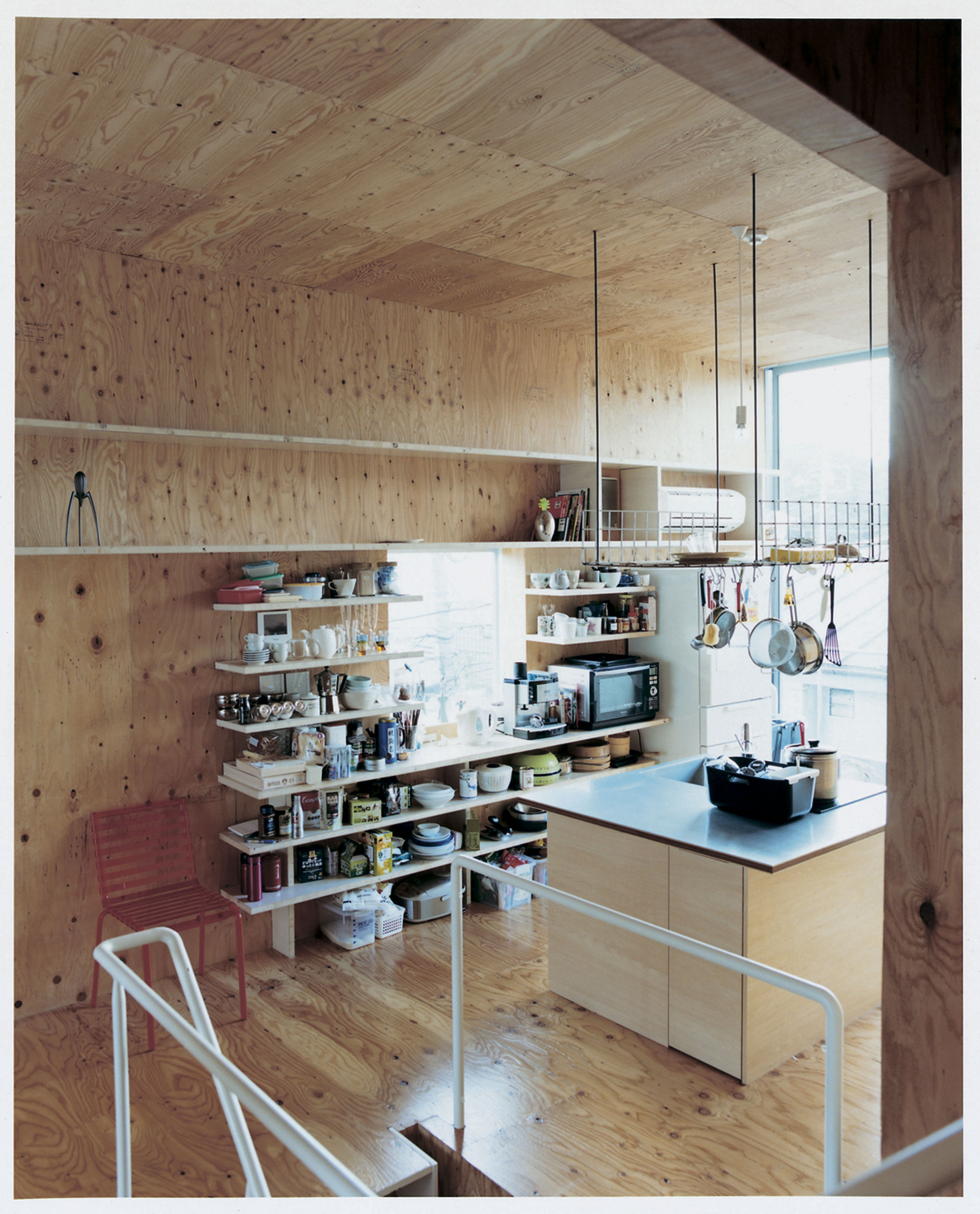

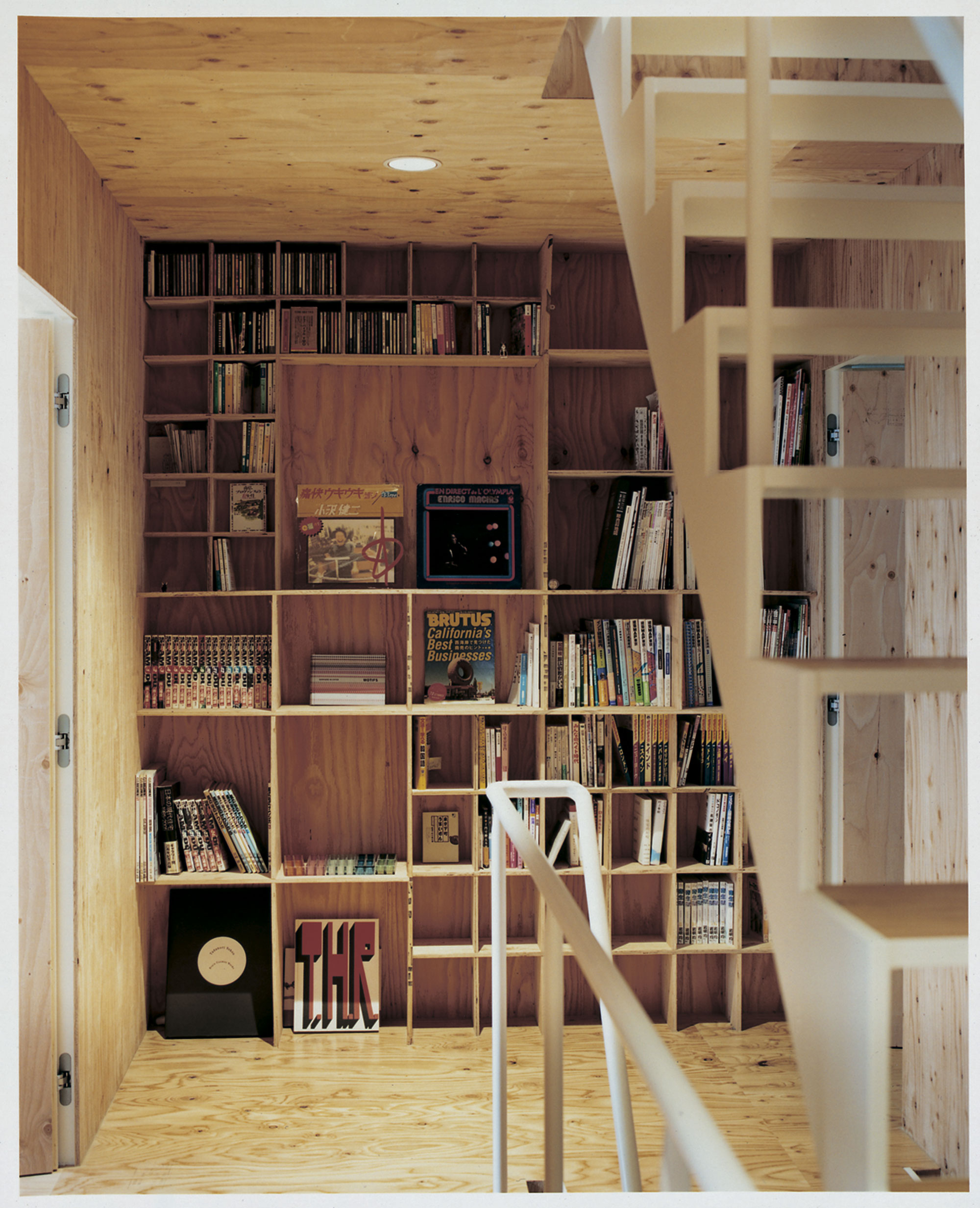

In configuring the building’s internal spaces, Shinohara and Uchimura strove for a balance between the residents’ need for alone time and the desire for social interaction. Share Yaraicho unfolds as a continuum of spaces: ground-floor entrance hall aside, a central staircase winds upwards to internal bedrooms and terraces, a kitchen and dining room for residents, and a rooftop garden for solo contemplation and reflection. The architects’ choice of wood and polycarbonate for the internal facades lends a sense of warmth and luminosity to the interiors. Even the furniture reflects the spirit of harmonious communality – it was built by the project’s first residents.

Shinohara explains that Share Yaraicho operates entirely as rental housing. Of the seven current residents, Shinohara reveals that over half are designers, including Uchimura, who has lived there since the project’s completion. The household operates largely on the basis of self-organisation; simple housekeeping rules, set up by the building’s first group of residents, remain largely unchanged some five years on. Uchimura plays a key role in facilitating the success of the shared-living arrangement by supporting communication among the various inhabitants, who often have differing life schedules. While living close to share-houses is often considered undesirable in Japan (“Young people often don’t care so much about their neighbours,” Shinohara explains), Share Yaraicho’s approach encourages an ongoing engagement between the building’s residents and the local community. The project’s owner, who lives nearby, coordinates relations with the neighbourhood, and all Share Yaraicho residents are members of the local neighbourhood association.

Five years on, Shinohara is looking for new ways to address evolving concerns: “Even now, most shared-living spaces are for single young people. However, the number of single elderly dwellers is increasing and has become a more serious problem. [Elderly people] need new lifestyles.”

Thank you, Shinohara-san, for your thoughts on architecture (and for your architecture!). This article was originally published in Assemble Papers #8. You can find your closest stockist here for a physical copy of this work. Check out more of Spatial Design Studio here and A Studio here.