Re-thinking border building

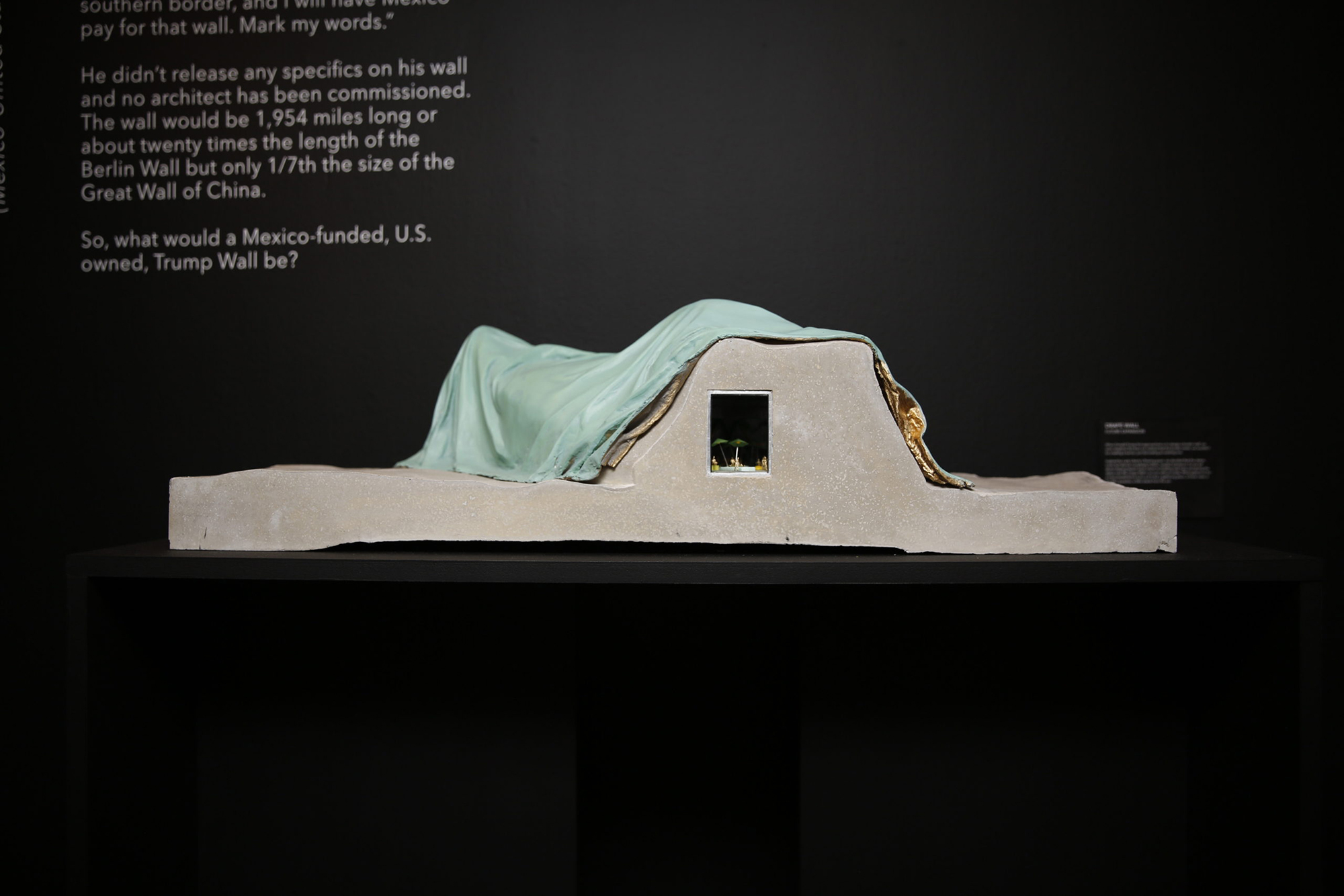

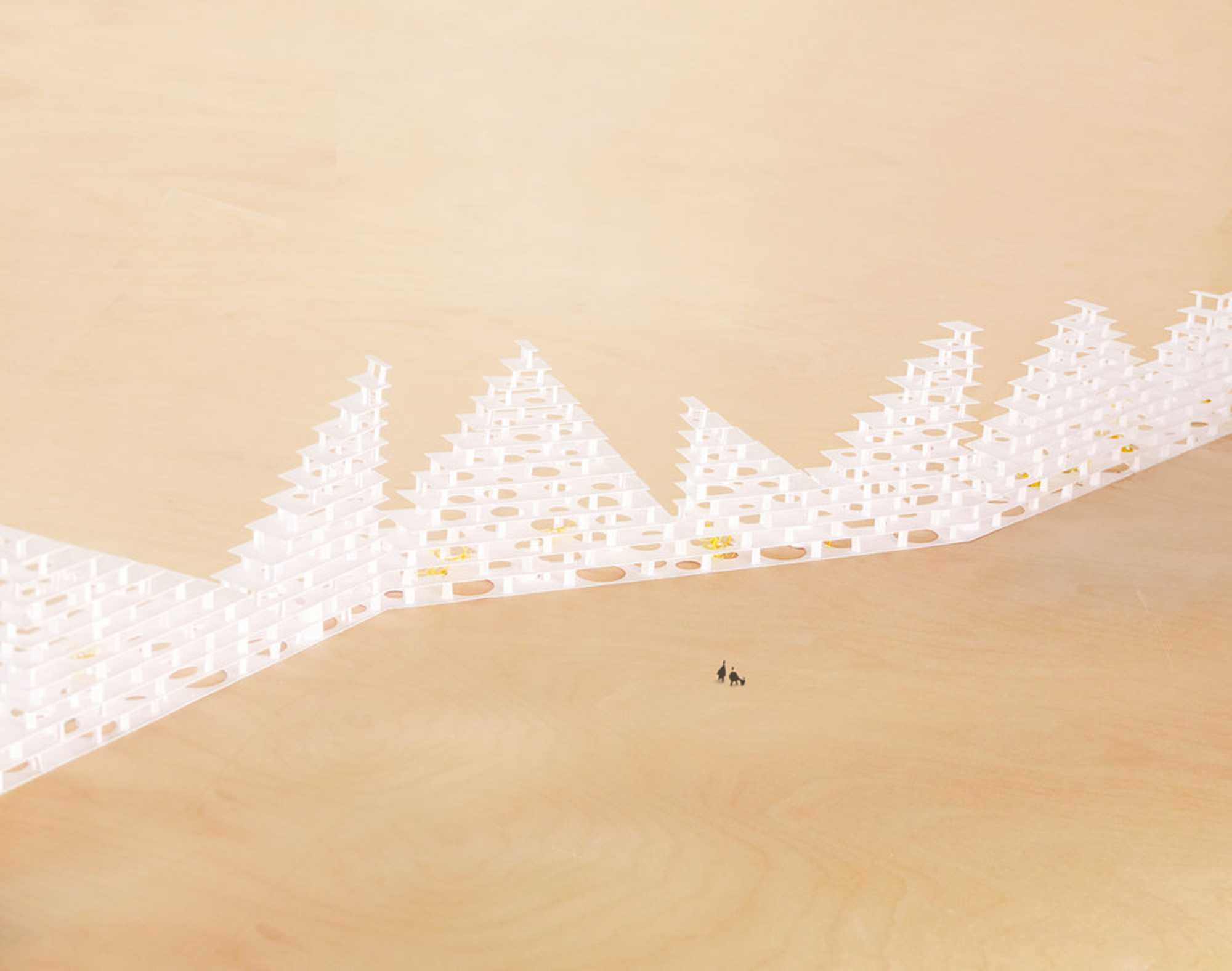

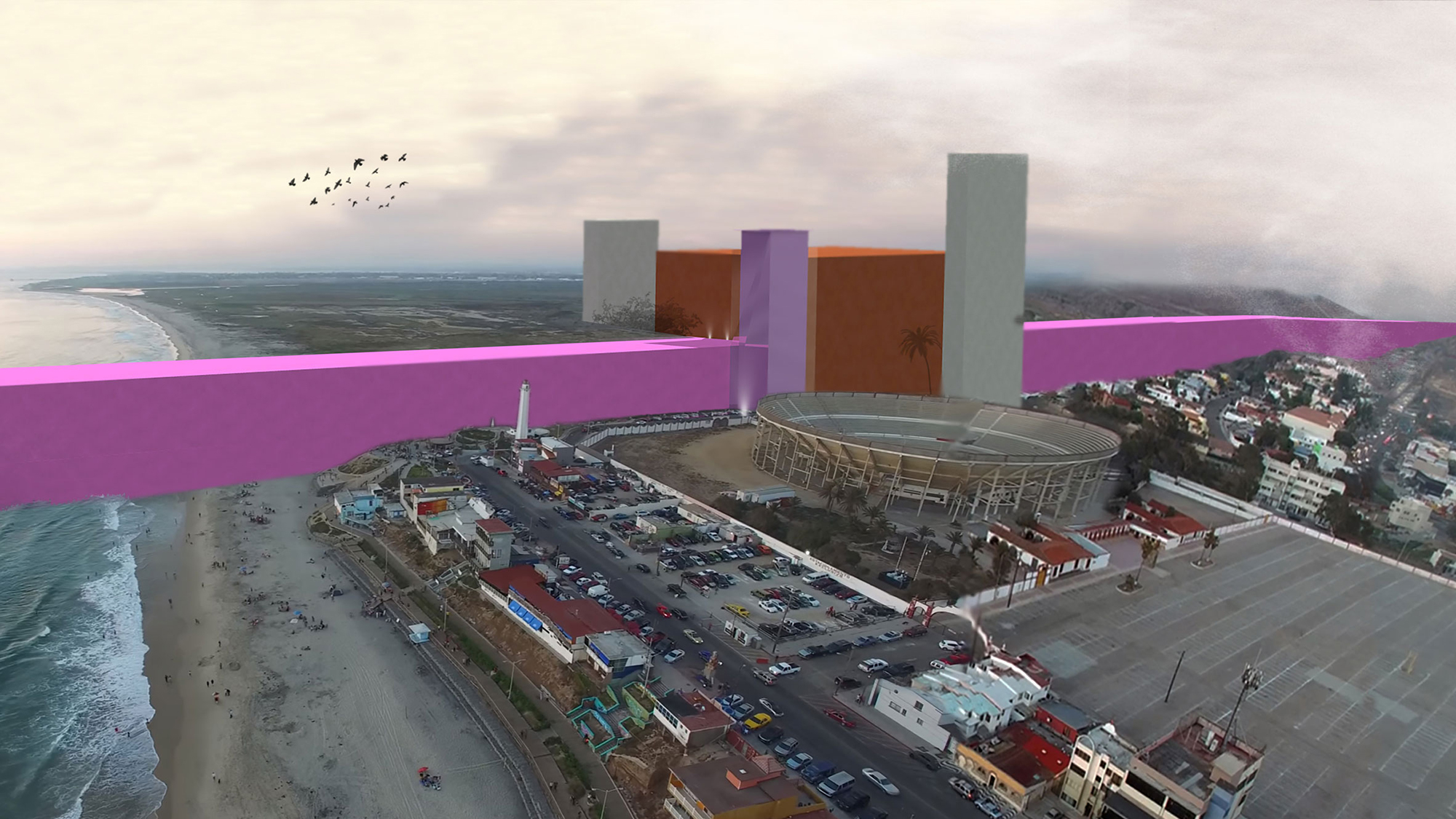

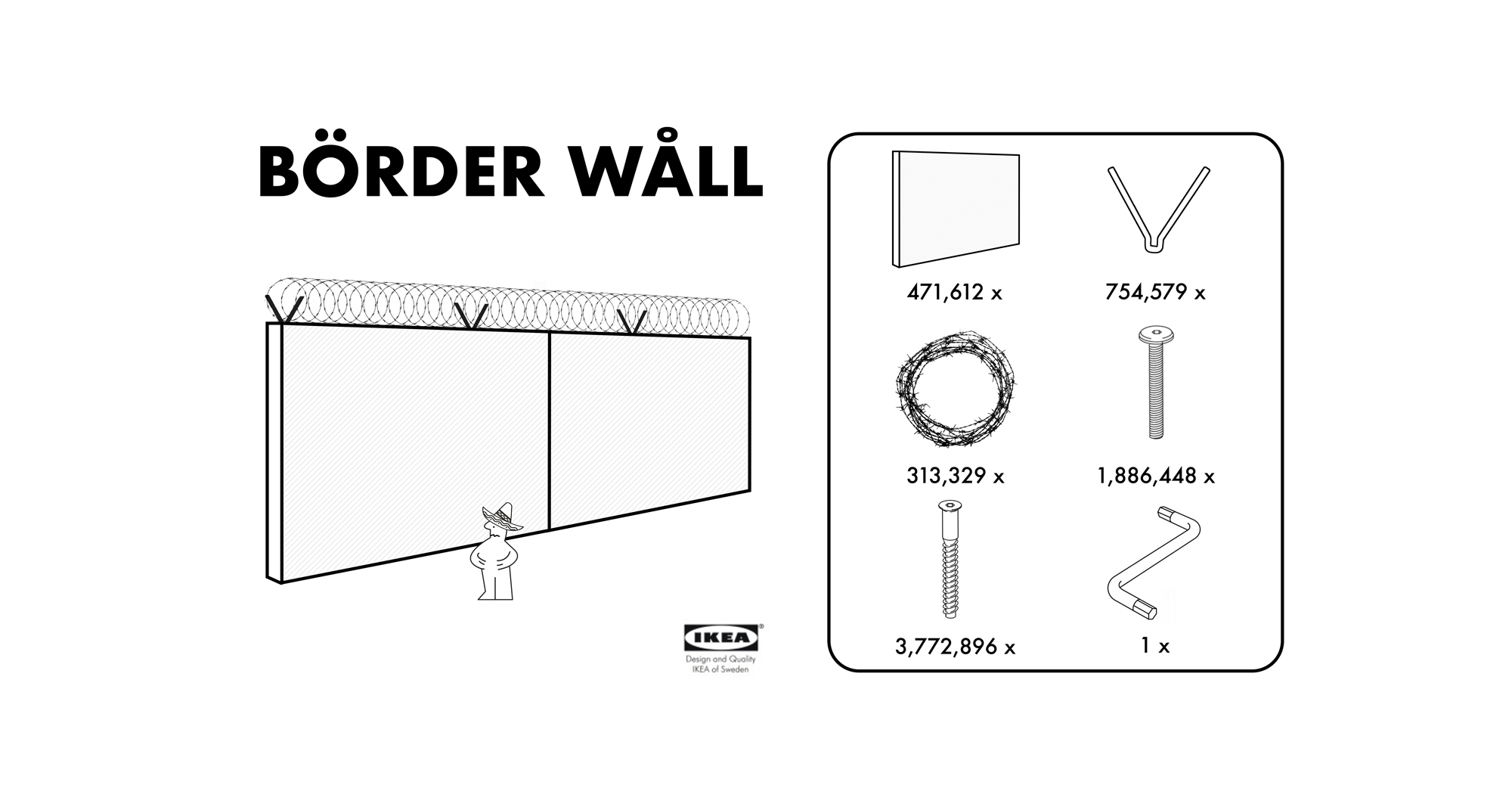

On a Wednesday night in late September, I joined a small audience gathering in the basement of the Center for Architecture in Greenwich Village for an exhibition of designs for a wall between the US and Mexico. At 5×5 Participatory Provocations, 25 architectural models were on display in response to a range of fictional future scenarios: Lunar Resorts, Investment Towers, Drone Ports, NSA Community Branches, and the most imminent of them all, Trump Walls. The playful physical models of various walled futures along the US-Mexico border were skillfully and immaculately produced with aesthetic detail embalmed in resin, painted plaster, sand and even cast concrete.

I was at once overwhelmed and confounded by the articulation of these objects materializing across various registers of reality. Architects deal with walls and their materiality, extent and design all the time, and we encounter walls and borders with such frequency that they simply escape consciousness. Yet, with the Border Wall Funding Act of 2017 introduced to the US Congress this April, and heavily contested wall prototypes currently being constructed, I began to wonder: what is it that transforms a wall into a political technology of separation? Beyond the simplistically aesthetic and physical, how should we conceive of its implications on communities, on the fabric of society?

Walls, boundaries, borders… From building construction to map reading, we have come to regard these terms with comfortable familiarity, as ubiquitous and necessary. A quick trip to the Oxford Dictionary clarifies a wall as “a continuous vertical brick or stone structure that encloses or divides an area of land,” or “any high vertical surface, especially one that is imposing in scale.” What is left out of the definition, however, is its implied intentionality: walls don’t accidentally happen. Also omitted is the notion of land ownership: there are two sides to every wall, two (or more) parties involved. A “wall” is constructed within a socio-cultural space, tied to all sorts of decision-making and inter-party negotiations—and thus, also already political.

Boundaries and borders are defined by Oxford as more abstract concepts, with the latter directly relating to political jurisdictions (“a line separating two countries, administrative divisions, or other areas”). Therefore, a border wall encodes a physical structure with geopolitical determination, in which government concepts are given material permanence (brick, stone, and today, concrete, steel and barbed wire). It features the ability to solidify a political ideal into real ‘fact”. It is worth noting that not all borders are necessarily walls: moats and trenches have historically been deployed around Medieval fortresses, effectively creating a bordered ‘island’ of deterrence, while more invisible airspace borders produce rules for flight paths overhead. Demilitarized zones (e.g. Korean DMZ) are thickened borders with walls, acting as a buffer zone between warring nations… We could go on. But I would like to point out how quickly these definitions have escalated; in the span of a paragraph we have gone from a harmless building element to highly-charged spaces of conflict between national powers.

Donald Trump captured the public imaginary by describing his US-Mexico border wall proposal in predominantly aesthetic terms: ‘impenetrable’, ‘tall’, ‘powerful’, ‘beautiful’, now also ‘transparent’. Yet aesthetic contemplations alone are a smokescreen; they don’t get to the heart of what walls really do. What’s not in a physical wall that nonetheless produces real consequences?

The border wall is, importantly, to be recognized as a legal apparatus: it wields the ability to exert invisible yet incredible forces upon people, places, memories and landscapes. Where walls go up, legislation is reified in space, making or breaking property ownership, access to resources, political and human rights, citizenship status and so on. Trespass becomes an enforceable criminal offence, and neighbours quickly begin to look like threats. Entire neighbourhoods (one thinks of increasingly normalized gated communities) might effectively become fortresses.

In Strangers as Enemies: Walls All over the World, and How to Tear Them Down (FrancoAngeli Edizioni, 2012), French philosopher Étienne Balibar explains that the figure of the alienated stranger transforms, with the insertion of a defensible wall, into the figure of a universal enemy or criminal. The injustice is that the ‘enemy’ characterization is placed on precisely those being subjugated by the wall – the ones who are in actuality being suppressed, enclosed or excluded through a wall they never asked for. The barbed walls encircling Manus Island’s detention facilities, for example, created an image of asylum-seekers as dangerous or untrustworthy figures trying to unlawfully enter Australia, even when asylum-seekers were, paradoxically, fleeing from sources of danger. In fact, reality presents the very opposite: Australia’s system of mandatory offshore asylum-seeker detention was repeatedly called out for directly contravening international law and has been submitted before the International Criminal Court as a ‘crime against humanity‘. The seemingly-passive detention center walls and the political structures that produced them should, instead, be the subject of contestation.

Giorgio Agamben is an Italian philosopher whose political theory has also weighed heavily on today’s border debate vis-à-vis law and citizenship. Building upon the influential writings of Foucault and Hannah Arendt, in his book State of Exception (2005) Agamben identifies in contemporary politics a dominant paradigm of government which he terms the “state of exception”: an “ambiguous, uncertain, borderline fringe, at the intersection of the legal and political”. This condition can emerge in calls for national safety and states of emergency, where the need for immediate response prompts governments to act unilaterally by suspending the normal rule of law. Trump’s adoption of a fervent border-wall rhetoric to assert territorial sovereignty springs to mind, claiming to protect the freedoms of those on the ‘sovereign’ side. Border-walls can also be immaterial, as exemplified by Trump’s numerous executive orders for a ‘Muslim ban’, which would draw all sorts of discriminatory lines through international transit that serve to ensnare a democracy proud of its diversity. When a border is made exceptional, that is, outside the realm of normal judicial oversight, it is difficult to prove if an action is ‘right’ or ‘wrong’. This ambiguity allows the sovereign power to engage in otherwise unthinkable transgressions, such as the forcible dismantling the rights of those on the other side of the not-so-proverbial fence.

But the border wall is also a maker or breaker of financial and cultural assets. In addition to the infrastructural costs of its construction, it is easy to see how real-estate value in areas along defensible walls might plummet, or how industries such as tourism might divert in search for safer, scenic routes. Entire community networks may be made to relocate, dismantling livelihoods and national identities along the way. This is evident in the solid wall dividing Palestine from Israel in the West Bank and Gaza, whose snaking form was rerouted numerous times by political and religious motivations, pressures from wealthier suburbs and ‘land-grab’ of Israeli investors. International rights groups also fought for adjustments to the wall-line. Its resultant form separated Palestinian farmers from their farmland, bisected existing neighbourhoods with less lobbying power and cut residents from community services, amongst other troubling consequences. Subsurface resources such as aquifers, oil and minerals were also divided by wall-making, raising issues of access, ownership and survival. On a more speculative architectural scale, Rem Koolhaas’ 1972 thesis, ‘Exodus, or the Voluntary Prisoners of Architecture’, dystopically narrates a programmed metropolitan wall (alluding to the Berlin Wall) cutting through London city, within which citizens seek freedom by self-imprisonment. This is clearly a severe radical polemic to be making- yet it is described in completely banal terms, with classic Koolhaasian ambivalence. There is, of course, the question of ongoing wall maintenance and operation, themselves costly logistical endeavours; for a wall of a large scale to ‘work’, significant administrative manpower is required, along with security checkpoints, patrollers, carparks, holding centers, roadways, tunnels and other politically motivated infrastructures. When one calls for a “wall”, an entire web of unspoken conditions and effects are invoked which extend far beyond a simple line on the map.

As the night progressed with celebratory lightheartedness, I grew progressively more anxious. In a later talk, the curators and architects discussed the conceptual ideas, exhibition logistics and creative decision-making behind each model. The word “wall” was frequently used yet unburdened by all its other invisible connotations. I wondered if by entertaining the architectural problem of border walls through, we were somehow unwittingly legitimizing border-making as a form of entertainment. During the panel Q&A, someone asked what other themes were being considered for future exhibitions and was met with an offhand response, “…maybe refugee camps?”. No one else seemed to balk. I should not understate my own complicity – I too had a plastic cup of champagne in my hand provided by the event. Yet as an actor set within this network of contradictions, conflicts and distractions one might call contemporary life, we are called to directly respond to the contentions borders and walls present, yet not trivialize or fetishize conflict situations – a double-bind. What do we do now?

Sometimes walls are produced in order to bring public light to its very human implications. The State of Exception/Estado de Excepción held earlier this year at The New School, Parsons, constructed a ‘wall of backpacks’ left behind by migrants crossing the Arizona desert, alongside displays of found clothing, interviews and videography taken along the US/Mexico border, in order to articulate the fleeing migrant’s wrenching journey of danger. Artist Plastic Jesus constructed a 6-inch mini-wall around Trump’s Hollywood Walk of Fame star, stopping tourists in their tracks and taking on a second life in social media. Berlin-based ZK/U has established a transdisciplinary exchange and art residency initiative to promote international exchange on global issues, and recently hosting Chilean artist Veronica Troncoso’s project on opening borders and crossing boundaries. Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation (GSAPP) has reassessed its own academic boundaries, with a politically cognizant series titled ‘The First 100 Days’ (now in its ‘Another 100 Days’ phase) enabling faculty and students from all departments to collectively discuss, organize and plan for changes to come during the Trump administration.

Border walls are being erected around the world, others (however proverbial) are coming down. And while positive transformations feel slow and small, it is by actively critiquing these technologies of separation, challenging their implied permanence, making familiar those who were unjustly rendered strangers, and finding alliances for alternate ways forward, that we might begin to invent new technologies of resistance.

A warm thank you to Amelyn Ng for her insightful investigations into the social and political implications of border-building and her suggestions on how we might approach engaging with issues of global significance. Find out more about Amelyn’s research over at her website here.