Rethinking the High-Rise Life

I’ve spent most of my life living in apartments. Eight, to be exact.

From multi-residential towers that cover the dense island-metropolises of Singapore and Hong Kong, to the apartments emerging all across inner-city Melbourne, I have by now assembled a somewhat comprehensive taxonomy of modern leisure facilities available to those who choose the high-rise life. Swimming pools, saunas, personal gymnasiums, ornamental roof gardens, tennis courts, private movie theatres, barbeque zones, foyer seating areas, sky-decks…

The list of strata titled real-estate terminology is almost encyclopaedic. Yet, even in their myriad configurations, the activities and social interactions produced seem strangely monotonous and prosaic. It was the homogenous quality of the modern apartment typology that ultimately made my cultural transitions into each successive neighbourhood (or entire city, for that matter) virtually effortless. The comforting familiarity that came with modern planning had inadvertently masked the fact that I had effectively moved into a new vertical community full of different people, local histories, context and knowledge. Perhaps most symptomatic of this programmatic genericism was my growing obliviousness to this half-residential, half-common intermediate social realm; a nondescript spatial glue that welded apartments together in a kind of rationalised terrain vague.

The older I got, the more predictable apartment culture became. Over time, I felt less and less inclined to explore the grounds on my own terms or figure out who my neighbours were, despite my natural reserves of curiosity. After all, these facilities tended to be empty for much of the day, and anyone I chanced upon at the gym or pool kept to themselves, some even displeased that I had intruded on their personal moments of leisure. I quickly learned that many residents frequented common spaces (ironically designed for social activity) at times when there was no one else around. These were, incidentally, the same people who would smile back if I acknowledged them at the local market or on the street.

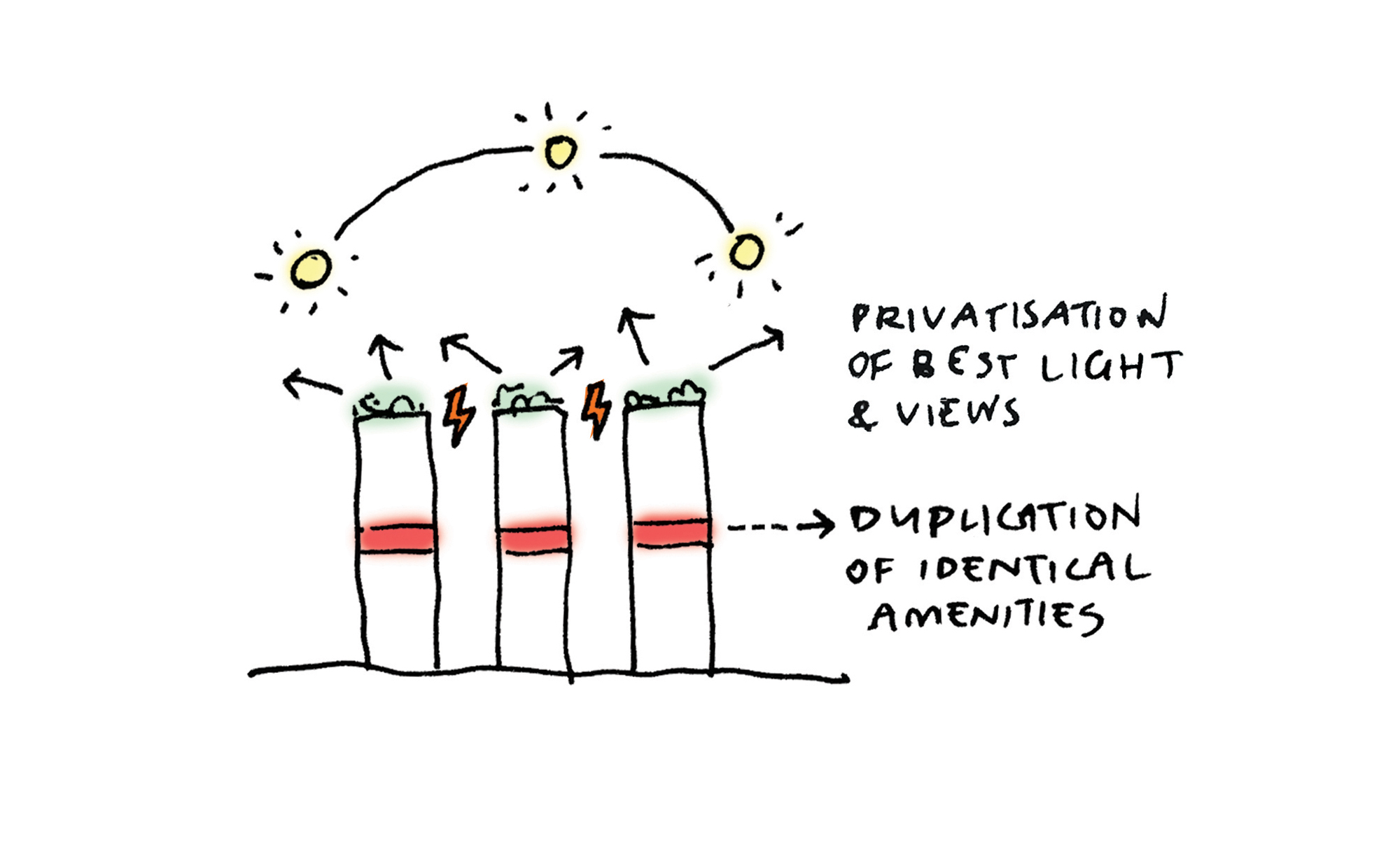

Why is this phenomenon of passive solitude found in so many apartment buildings everywhere, even to the most gregarious of residents? How did we come to believe that domestic introversion and its standard suite of well-kept leisure facilities form the aspirational benchmark for inner city living and a better quality-of-life? Some say anti-social behaviour is inevitable; that there is a critical mass for people living together in high-density environments, after which feelings of anonymity creep in and the value of privacy over social networks increases disproportionately. Others might argue that it comes down to one’s own lifestyle preference. Multi-residential homogenisation appears inconsequential at the level of the individual property, the single investor or tenant. However, at the larger scale of a rapidly growing city, when viewing the production of high-rise housing stock as a cumulative whole, cut-and-paste apartment programs begin to present discomforts and potential loss of opportunity.

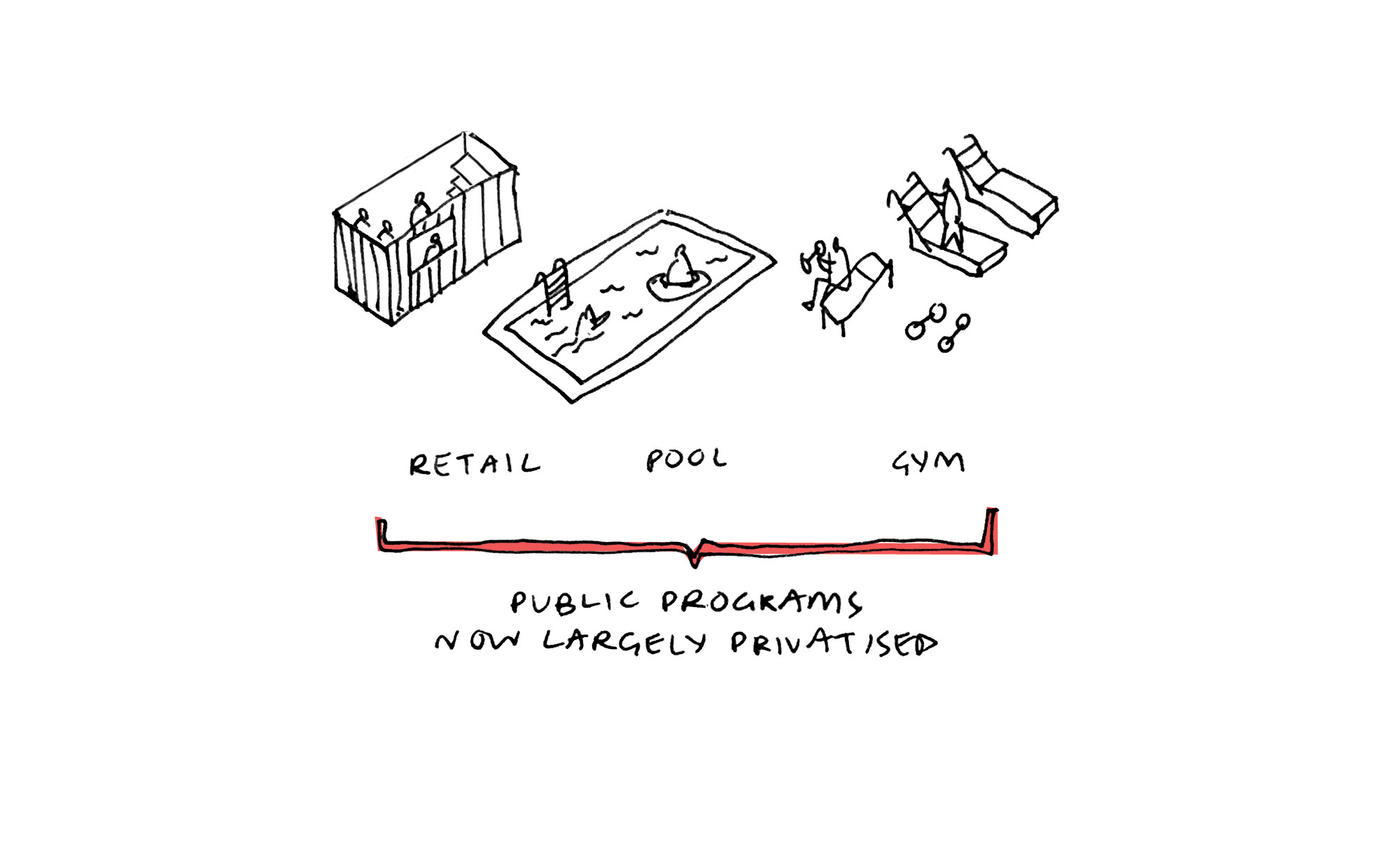

For example, take the Docklands in Melbourne, or Wood Wharf in London, in terms of the neighbourhood amenities they provide. To date, the Docklands precinct has zero primary schools, yet it has thirty-five private gyms (yes, I counted). Since when did the desire for fitness centres outweigh the need for primary education? How did we get our neighbourhoods into this situation?

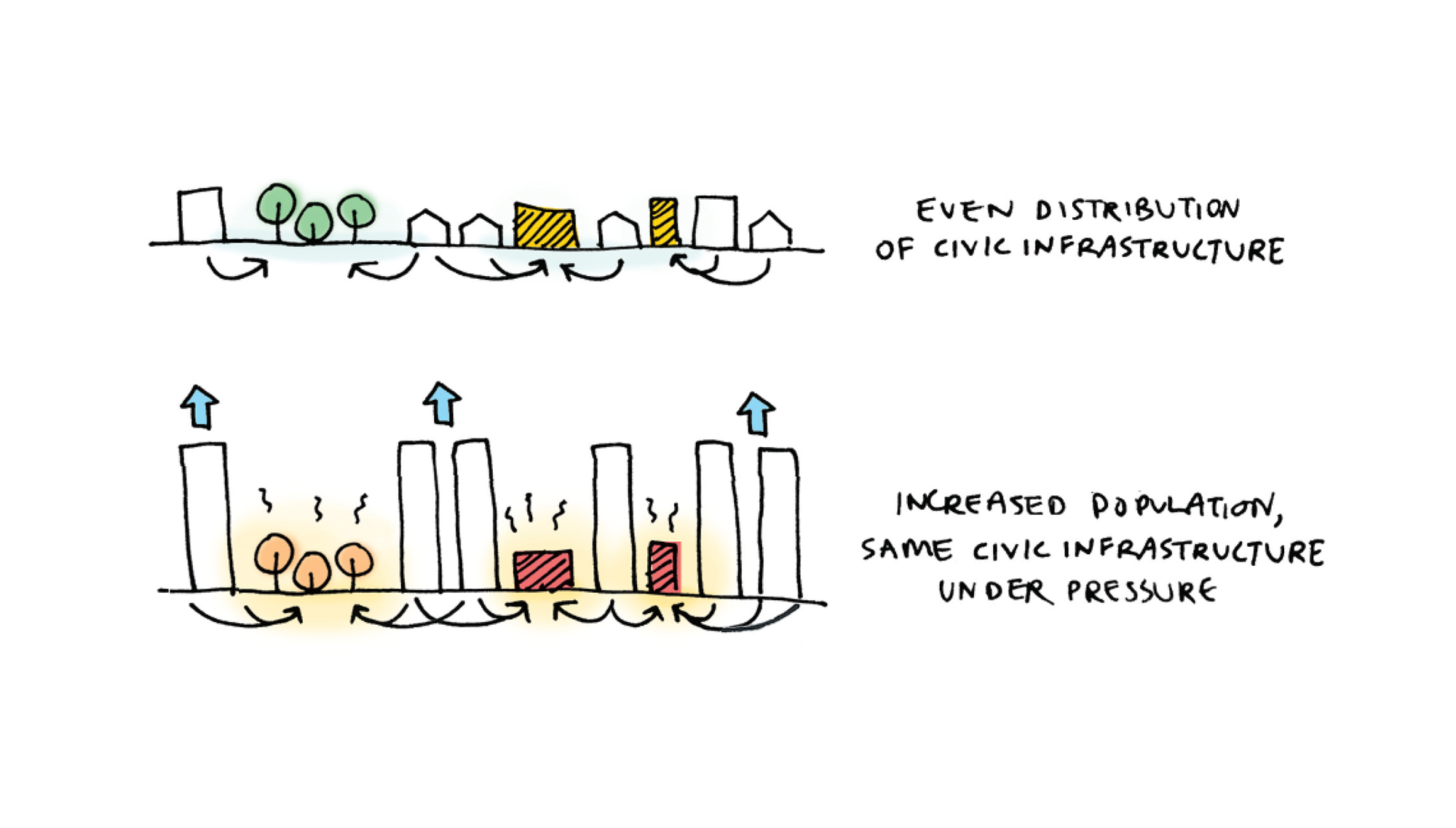

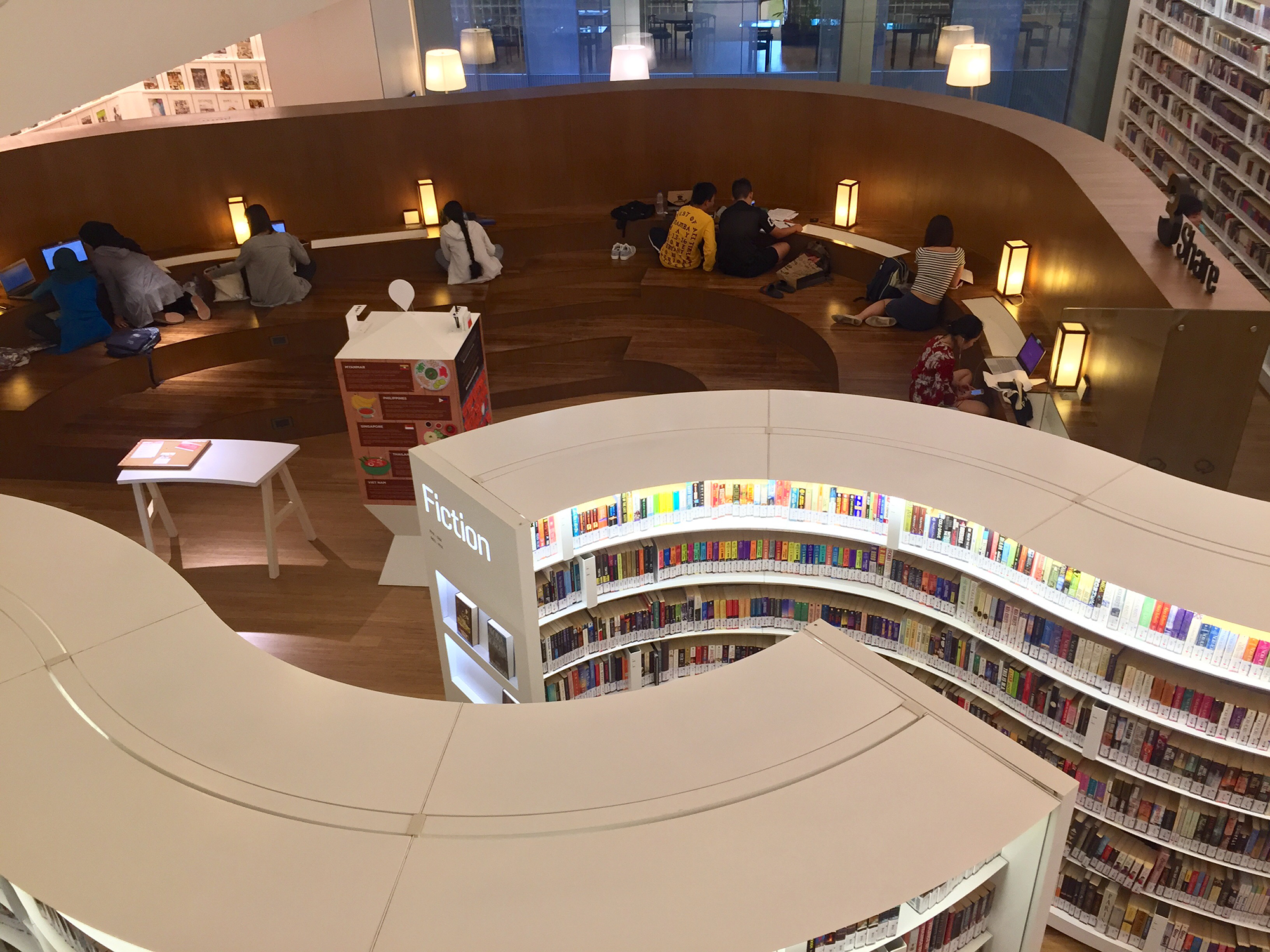

Building spaces for new citizens means more than new housing. It means decent access to new childcare, classrooms, produce markets, pet-friendly parks, libraries – not just new generic leisure. Existing public infrastructure could certainly be upgraded, but their expansion may be limited by the shrinking of available space. Meanwhile, private apartment towers spring up left, right and centre. Could some of their underutilised communal spaces somehow be appropriated for broader civic needs, perhaps even for amenities other than leisure?

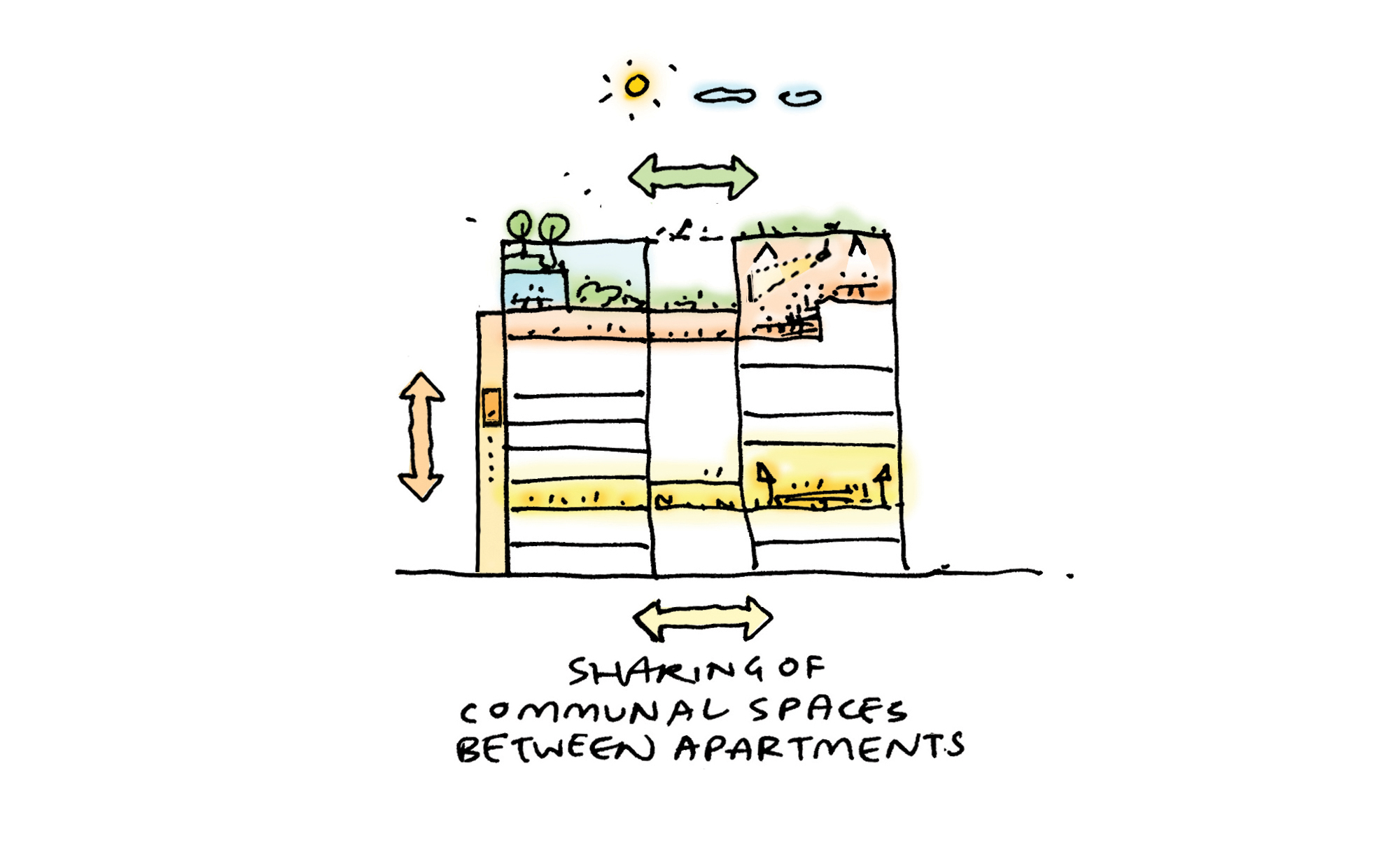

It might be a matter of rescheduling access hours to include public users – for example, allowing community organisations to book function rooms for their meetings during office hours, when working residents are largely away from home. Then, if one is allowed to dream, a public access lift might be fitted to take visitors directly up to, say, the public library level, where students (who make up a considerable percentage of the high-rise rental population) are able to study outside of their small studio units, while at non-peak hours volunteer committee members take turns organising reading groups or roof-garden excursions for their children.

If our cities of tomorrow are to be as diverse and culturally vibrant, it would be wise to consider a range of demographics when developing apartment housing, beyond the working professional and the temporary student. Families would be more encouraged to live in long-term owner-occupier apartments if there were adequate learning and playing facilities for their children, and closer proximity to school zones. If such programs were folded into the inner-city residential mix at walkable distances, alleviation of traffic congestion would follow. Generic luxury facilities tend to attract a limited and exclusive demographic, which, when applied en masse, exacerbates stratification over time.

So who currently manages these shared spaces? It is standard practice for a third-party body corporate management company to assume a caretaking role and manage, administer, repair and maintain common property for the convenience of its residents. Most facilities management companies provide standardised services for reasons of commercial efficiency: hiring a single specialised contractor to manage, say, heated pools over five buildings generally yields consistent service, and lower administrative costs than hiring several separate contractors to maintain a variety of different amenities across those five buildings. Yet from an environmental and socio-cultural perspective it seems incredibly inefficient, maybe even absurd, to agglomerate identical low-priority amenities (five heated pools in a row!) and then grow accustomed to their under-utility. Perhaps more facilities management companies should join the architectural conversation early, alongside urban planning and community consultation processes, rather than at the tail-end of the procurement process where it may be too late for any significant programmatic changes.

Here it might be worth mentioning the Pinnacle@Duxton, a large-scale housing project developed by Singapore’s Housing Development Board. Completed in 2009, it accommodates 1,848 units in seven towering blocks on prime land near the city’s business district. While expansive in plot size, it features an active and permeable ground plane, above which towers interconnect via a series of open-air bridges that also form a landscaped jogging track. A resident’s committee office, situated at ground-level next to the Tanjong Pagar Community Club, doubles as a ticketing booth for public access to observation decks at levels 26 and 50. Here, apartments co-exist quite comfortably with publicly accessible facilities such as playgrounds, a food court, basketball court, outdoor ‘foyer’ seating, an integrated kindergarten and early childhood centre at its entrance and public transport at its doorstep. My visit there, however brief, indicated that the solid block had become a field of negotiated spaces, trade-offs, exchanges and shortcuts; a high-density testing ground for future urban housing projects of comparable size and ambition.

When developers look to precedent projects abroad, it is almost too easy to adopt high-yield housing models without knowledge of that particular city’s living patterns, planning history and geopolitical conditions. Even at face value, it is evident that not all cities have the established infrastructure of New York’s 340-hectare Central Park (more than twice the size of Melbourne’s Hoddle Grid) to furnish its resident population with green inner-city open space for gathering and recreation. New neighbourhoods, such as the Docklands or Fishermans Bend, haven’t had the decades of layered cultural development for street life to thrive on its own. Blanket rules and zones look good on paper but often don’t cut it in real life; this is where interdisciplinary frameworks could come in, enough to encourage but not to stifle. Perhaps it is the initiative of the planner to review residential and public policies, or the creative invention of the architectural team working with facilities management companies to investigate potentials for cross-programming, or the broad-minded entrepreneurship of development partners who coordinate with each other, staging apartment projects in ways that collectively benefit the resultant urban block. Most likely it will take a concert of collaborative efforts across all stages of procurement, over a spectrum of disciplines in open discussion with each other and its public. In the end, good urbanism is negotiated.

The inevitable ubiquity of multi-residential dwelling comes with big civic challenges that can no longer be postponed or ignored. UN statistics continue to indicate the rapid rise of global population growth: by 2050, three in five people worldwide will live in urban settlements. To bring this closer to home: by 2050, Melbourne’s 485-hectare urban renewal project at Fishermans Bend is projected to vertically house 80,000 inhabitants. And this isn’t a distant speculation on the horizon – the wheels of policies and masterplans are already in motion; planning permits for residential towers up to 40 storeys are being approved as we speak. We are in an era where neighbours and commons should matter more than ever; where diverse demographics and flexible programs should not be nice-to-haves, but be seen as integral to the metropolitan neighbourhood’s long-term success. Be it at ground level or up above on the nth floor, when we start to redefine social infrastructures surrounding our high-rise life, we take the ‘apart’ out of ‘apartments’, in doing so making room for genuine public life to prosper.