What’s in a map? Greening Bourj Al Shamali

There’s a passage in Tanzanian novelist Abdulrazak Gurnah’s By the Sea (2001) in which the character Saleh Omar, an elderly Zanzibari man seeking asylum in Britain, considers the power inherent in maps. “Before maps, the world was limitless,” he reflects from the small British seaside town where he awaits the outcome of his case. “It was maps that gave it shape and made it seem like territory, like something that could be possessed . . . Maps made places on the edges of the imagination seem graspable and placable.” It’s a telling rumination on the political nature of the map – an age-old tool that’s practical and supposedly authoritative, yet also deeply precarious (the term ‘cartographic anxiety’ is sometimes used to describe the dissonance between geographical representations of the world and the cultural and socioeconomic realities of how we actually experience it).

At Bourj Al Shamali, a Palestinian refugee camp situated in southern Lebanon, the settlement’s 23,000 current inhabitants have never enjoyed the privilege of owning a detailed map of their 135,000m2 grounds. This isn’t to say maps of the area don’t exist – they do, only they’re classified documents protected by local authorities and international organisations who view them as potential security threats. (Public maps of Lebanon, whether on paper or on Google Earth, often depict refugee camps as grey splotches.) Originally built in the mid-1950s as a temporary refuge, over the past seven decades Bourj Al Shamali has transformed from a tent settlement to its current state, where the distinction between ‘permanent’ and ‘impermanent’ is increasingly obscured. Today, homes in the camp are made of concrete, asphalt, brick and stone, with some covered in political graffiti and street art evoking an erstwhile Palestine long left behind.

In recent years, Bourj Al Shamali has become home to large numbers of Palestinian refugees from Syria, placing added pressure on the already overcrowded living conditions in the camp. A map would open up multiple doors for the Bourj Al Shamali community to address some of its more pressing planning issues: not only could the area be organised into different neighbourhoods (currently there are informal zones named after agricultural villages in Palestine’s Safed and Tiberias regions, though no street or alleyway is adequately signposted), but a map could also assist in visualising priorities for each of these areas, such as the unreliable electricity supply in many parts of the camp. A map would also aid in maintaining this infrastructure over time.

Enter Greening Bourj Al Shamali: a pilot urban agriculture program aimed at improving living conditions in the camp through the creation of its first public space. Almost anywhere else this would be a feasible objective – but in the overcrowded, haphazardly planned Bourj Al Shamali, this seemingly straightforward task becomes a delicate political challenge. The first step? Figure out the best way to obtain a map of the grounds.

Humanitarian worker and ex-UN staffer Claudia Martinez Mansell is the co-founder of Greening Bourj Al Shamali, alongside Mahmoud Al Joumma ‘Abu Wassim’, who runs the Beit Atfal Assumoud vocational centre in the camp. “Our intent here is not malicious, and security is a legitimate concern, but such policies [that render current maps of the camp unavailable to residents] perpetuate the notion of the camp as a dependent and passive beneficiary. It perpetuates their dispossession, depriving camp residents of control over their geospatial reality,” says Claudia, who first connected with the camp in 1998 as a volunteer at the vocational centre.

“Bourj Al Shamali is currently going through quite a particular and inspiring political moment. There are several factors: the stalled negotiations between Israel and Palestine; the increasingly remote prospect of a negotiated agreement on the situation of refugees; the defunding of the UNRWA [the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East]; and local frustrations with the wrangling of Fatah and Hamas, which has led to political paralysis within the Popular Committee in the camp.”

In a different environment, the area could be easily mapped by drone, but to employ such a “symbolically threatening” device, as Claudia puts it, poses more complications than solutions. For this reason Claudia, together with a new, politically neutral camp committee, and a group of students living in the camp (none trained geographers or mappers) engaged an organisation called Public Lab to assist.

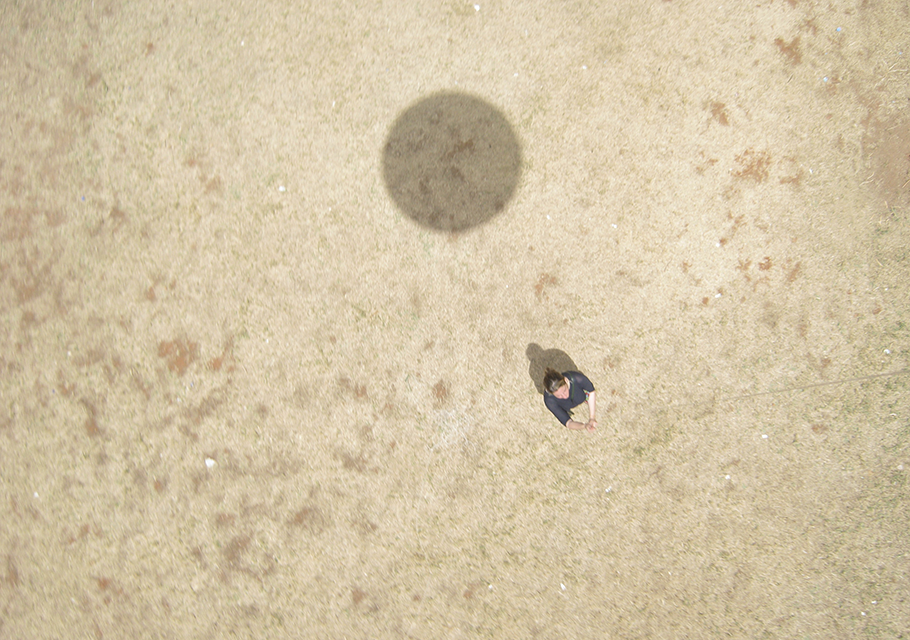

Public Lab, founded in 2010, is a network of organisers, educators, technologists and researchers that connects people to open-source DIY techniques for data-gathering and research to allow participation in important decisions affecting their communities. Among Public Lab’s various toolkits for data collection is ‘balloon mapping’ aerial photography – a cheap digital camera attached to a large balloon on a rig fashioned out of an everyday plastic drink bottle. [We held a balloon mapping workshop at MPavilion in December 2016 – Ed.] In 2010, balloon mapping was employed by a group of MIT students to document the extent of the damage caused in the Gulf Coast by the Deepwater Horizon/BP oil spill that same year, demonstrating the colossal potential of this easy and relatively low-cost ‘citizen science’ method. It has also been used to document protests and other social events.

In the populous Bourj Al Shamali, balloon mapping has proved an effective way for the Greening Bourj Al Shamali team to connect with community members throughout the mapping process – a giant red balloon being flown anywhere up to 200 metres in the air is nothing if not a conversation starter (especially when navigating the narrow streets of the camp, cloaked with overlapping wires and cables). “The string tying us to the balloon meant that we had to be present when we were mapping, climbing on people’s roofs and interacting with passers-by who asked questions,” says Claudia. “The visibility inherent in this kind of ‘umbilical cord’ was a way of winning trust – the mapper is in the map. If you look closely at our finished product, you can see the mappers in various locations.”

Firas Ismail, a 19-year-old nursing student and lifelong resident of Bourj Al Shamali, has been leading the mapping activities at the camp alongside fellow student Mustapha Dakhloul, also 19, since the project’s inception. We’re speaking over Skype. “Most people are surprised when they see it. Children love balloons, so of course they always want to touch it. Other people always want to take pictures with it,” says Firas.

Not everyone is so obliging, however, and the team is occasionally met with resistance. Mustapha recounts a time when they ventured just behind the camp: “We had some problems with political forces like Hezbollah, who took the memory card for the camera, returning it after one month. Two or three times, the balloon was also shot down.”

Claudia also speaks about a time when a mischievous group of kids from the camp thought it would be funny to attack the balloon with a pellet gun. “But [the residents] who dislike it are very small compared to those who like it,” Firas is quick to add.

In By the Sea, Saleh Omar recalls his first encounter with a map – in the classroom when his teacher drew on the blackboard a line travelling westward from India all the way back around to China, depicting “half the known world in one continuous line with his piece of chalk”. Such is the nature of the multifaceted map: its fluidity an essential aspect of violent colonial projects, and the cause of unease for both victims and enforcers of territorial sovereignty. How can a map – a concept so inherently frail, like chalk on a blackboard – hold so much power?

At Bourj Al Shamali, Claudia says the supervision of the local committee and the support of Mahmoud Al Joumma was instrumental in earning the trust of the residents, as well as outside forces. “A major effort was mounted by key members of the local committee to inform the community, both by speaking to the various factions within the camp, as well as the Lebanese Army. This took time – the actual mapping only took a few days, but the preparatory work took over a month and a half.”

With the data collection process now complete, the next stage in the project is to stitch together the photographs and work on producing a final map through a series of a community workshops. And, Claudia explains, though foreigners need a permit to enter the camp, Mustapha and some of the local boy scouts are also planning to build a noticeboard with the map at the entrance to the camp “to make people feel welcome in the community when they arrive”.

Ultimately, Greening Bourj Al Shamali is an exercise in empowerment for its residents, enabling them to bypass bureaucracy in the development and improvement of the camp – their supposedly ‘temporary’ home. But for the likes of Firas and Mustapha, it’s the only one they’ve ever known. “We hope other people outside the camp will have some ideas they can share after seeing the map,” says Firas, who hopes the map will function as an advocacy tool for the camp and for the world outside to engage with it. “We just want everyone to know what’s inside Bourj Al Shamali, and the problems of the Palestinian refugees inside.”

Many thanks to Claudia Martinez Mansell for sharing her knowledge about Bourj Al Shamali over email and Skype, and for facilitating our interview with Firas Ismail and Mustapha Dakhloul. For further reading about Bourj Al Shamali, we recommend Claudia’s verbal sketch of the camp in Places Journal (April 2016) entitled ‘Camp Code’, from which some of the information about the camp’s layout was additionally sourced for this article. You can also visit the Greening Bourj Al Shamali website: bourjalshamali.org