The Robin Boyd Foundation’s living legacy

You’d be hard-pressed to find an architect in Australia who hasn’t studied Robin Boyd. Better still, the influential architect, known for his sensitive variation of modernism, is a household name that stretches far beyond the architectural elite. Boyd’s is a legacy that has endured in his expansive body of work, both built and written, lovingly upheld in no small part by the 2005-established Robin Boyd Foundation. Rachel Elliot-Jones visits its founder and director, Tony Lee, at the Foundation’s unmistakable headquarters in Melbourne’s South Yarra.

Tony Lee arrives on his trusty two-wheeler to let photographer Tom Ross and I in to Walsh Street, also known as Robin Boyd House II. We’ve been waiting on the timber steps that float up to the first-floor front door, nerding out about the building. It’s crisp outside but the trees are still fully leaved. The sky is grey and we’re happy about it; we know it’s the perfect light to see this place at its best.

The house is quiet inside, a change from every other time I’ve visited when it’s been heaving with film-watchers or seminar-goers. For more than a decade, Walsh Street has been a special kind of meeting place: a catalyst for discussion, busily advocating for a better understanding of design in the community through constant programming – the custodian of Boyd’s legacy.

It’s a house museum like no other; not an object to be gawked at but a place to be lived in, even if only for a moment. Shoes on, wine in hand, no finger-wagging if you sit on a chair and not a velvet rope in sight – this is Tony’s vision for Walsh Street and the Robin Boyd Foundation: to make the lived experience accessible.

In 2004, Tony was with the National Trust and charged with expanding its repertoire beyond its “collection of hand-me-downs” to acquire something that exemplified Melbourne and its architectural style. The answer in Tony’s mind was unquestionably Boyd. “Robin was a design evangelist whose whole output – whether it was architecture, writing, journalism, films or public speaking – everything Robin did was about introducing the public to a greater understanding of what design is and the benefits of design.” This awareness of good design that Boyd campaigned for, Tony thought, went hand-in-hand with the Trust’s mantle of conservation. If buildings are understood in terms of their contribution to architecture, it’s more likely the public will feel a duty to protect them.

Momentum for a Boyd acquisition grew through a dedicated open day curated by Tony and hosted by the Trust. There was an exhibition of Mark Strizic’s photography of Boyd’s work, a reunion of co-conspirators from Boyd’s office and a series of talks at Federation Square. Buoyed by the event’s success, the bones of a five-year plan to purchase a Boyd building began to take shape.

Walsh Street, the second of two homes Boyd designed for his own family to live in, was a lofty goal. Tony considered it “a kind of holy grail of architecture in Melbourne”; he knew it would demonstrate the pointiest end of Boyd’s oeuvre. “Robin said on many occasions that it is an architect’s obligation. . . to experiment, trial and initiate design on themselves . . . This house was inherently going to be an innovative building because he designed it for himself.”

The house had been out of the public eye, privately tended to by Boyd’s wife, Patricia. She had doggedly and determinedly maintained it since his untimely death in 1971, despite being left with a colossal mortgage, two children still studying to support and a reportedly hefty overdraft incurred by Boyd’s practice. (Boyd’s work was exceptional, but not lucrative.)

The Trust’s five-year plot became “not quite five days” when Tony learned that Patricia had coincidentally just put Walsh Street on the market. The Robin Boyd Foundation formed swiftly to swoop on this opportunity and purchased the house, initially under the auspices of the National Trust.

Soon after Walsh Street was welcomed into the fold, priorities shifted at the Trust and within 18 months the house was put up for sale again. The Foundation separated from the Trust and lobbied independently for alternative support. With an enormous mortgage to grapple with and a loan to pay off, architect Daryl Jackson became the Foundation’s loudest champion. His rallying cry in the ranks of the Victorian Government, the University of Melbourne and within the profession helped secure some initial funding, contingent on a strategic business plan that would demonstrate how the Foundation could achieve financial independence over time.

These unique economic factors are not the norm in house museums, usually the result of a generous bequest from the owner or architect (which often includes an allowance for maintaining the property too). The Robin Boyd Foundation’s financial circumstances necessitated rigorous activation that would fund its day-to-day operation, however the program itself, initiated by Tony, was a direct descendant of Boyd’s own work, inspired by the way he and Patricia lived at Walsh Street.

The regular talks series stemmed from the Boyds’ dinner table conversations. “When they were here in the house, [it] was a venue for discussion. While it was very sociable – and the dinner parties here were quite legendary – they weren’t just gregarious bashes. There were quite significant people sitting around the table, sharing information [with] a real concern for the betterment of our society,” says Tony. The Foundation’s DADo Film Society has provided another avenue for discussion, with recent film nights dedicated to a Brutalism love-fest, concrete love and Amare Gio Ponti (Loving Gio Ponti) (2015) – the fondness for the built form is palpable.

The Robin Boyd Foundation’s famed design open days (now coming up to their 30th edition) “are like a curated collection of artworks – there’s always a principal theme and buildings are selected to reflect that theme.” The series began with a group of Boyd and Boyd-influenced houses and has since explored influential apartments, émigré houses, architects’ own houses and so much more. Rather than being limited to Boyd’s work, the program is “a public statement of good design being ageless”.

Design education was a pillar of Boyd’s practice and Tony has sought to build on that. “Robin was very much about the urban environment, [so I thought] we could run workshops here that are [about] the role that architecture plays in creating the image of a city, or the culture of a city – and the importance of having buildings be respectful of streets and adjacent buildings.” To date, the program has largely focused on university studios developed in partnership with Melbourne School of Design and the City of Melbourne, but Tony hopes to add primary and secondary education to the bill in the coming years. “They may not go on to be architects but our agenda is to have a community that understands and expects good design.”

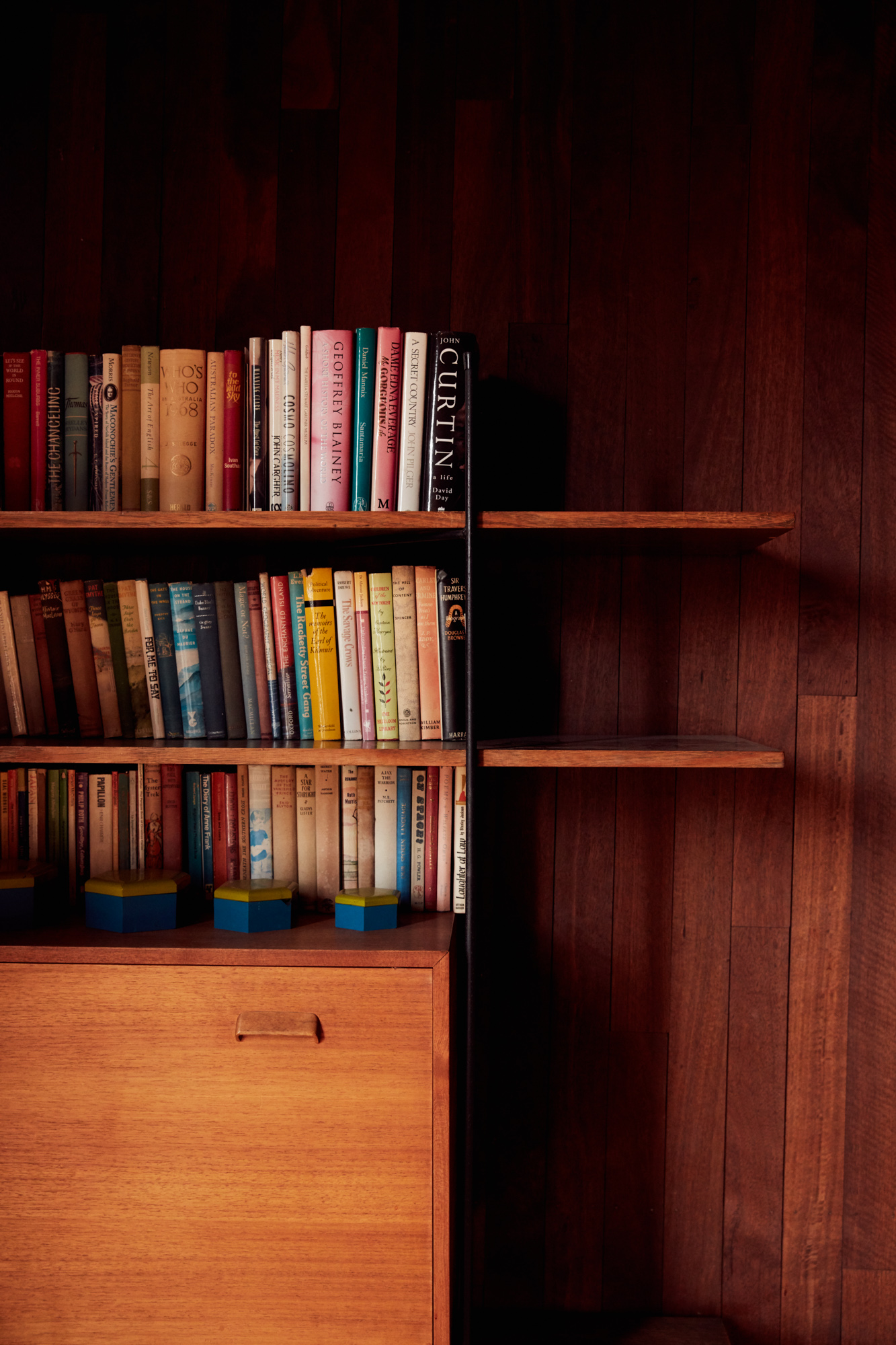

The Foundation is also working on an archive of Boyd artefacts and ephemera. Being situated at Walsh Street is a huge coup on this front. “Not only do we get the house, but we get this whole time capsule that represents Robin’s complete attitude to living. It’s an architectural biography of Robin and Patricia – everything in the house reflects their relationships, their lifestyle, their attitudes. And nothing in this house happened by accident – everything is conceivable in material, in construction, the furniture and the placement of the furniture,” Tony tells me as we perch on the red sofa, which, as we chat, I notice is in direct conversation with Tony Woods’s Man on Sofa (1967) hanging over us.

The archive function of the Foundation is not limited to the physical bounds of Walsh Street – Tony is fastidiously locating and cataloguing all the Boyd material he can find to make it publicly accessible online. There’s even talk of resurrecting the Boyd-helmed Small Homes Service (the Age and the Royal Victorian Institute of Architects’ service, established in 1947, for providing house plans by architects in the name of improving everyday home design), re-imagining it in a contemporary context to grapple with our current issues of housing affordability, urban density and the changing notions of family.

Today, Walsh Street endures not only as the living embodiment of a personal and architectural legacy, but a contemporary expression of the pivotal role architecture plays in our understanding of the world. It is, as Tony says, “a complete and absolute paradigm shift in how a house museum can be used.”

We thank Tony Lee for taking the time to share the Robin Boyd Foundation’s story with us, and Rachel Elliot-Jones for her way with words. To keep up to date with the Robin Boyd Foundation, visit robinboyd.org.au The thoughtful photo series is the work of one of our favourite photographers, Tom Ross. Find more of his work at brilliantcreek.com