Raumlabor Berlin’s spacebusting urban transformations

Berlin-based collective Raumlabor sees the city as a space for investigation, participation and endless possibilities. With much of its early work spanning the realm of temporary interventions, these days the nine-strong team of experimental architects is turning its focus towards more enduring urban transformations. After a recent visit to Melbourne, co-director Christof Mayer chats to Emily Wong about Raumlabor’s participatory approach, situated somewhere near the intersection of art and city-making.

Since its inception in the late ’90s, Berlin-based collective Raumlabor has worked on a kaleidoscopic range of projects, from urban interventions and masterplans to public art and collaborative building workshops. Driven by a shared interest in urban renewal and transformation, their site-specific and often self-initiated interventions aim to activate public space, imagining new possibilities for urban occupation.

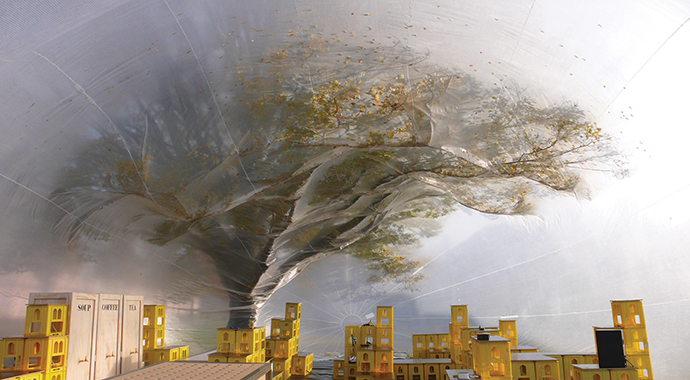

In 2005, Raumlabor constructed a mountain (Der Berg) in the defunct spaces of Berlin’s former Palace of the Republic, opening a dialogue about the city’s past, present and potential future. Kitchen Monument (2006–) – a roving, inflatable and inhabitable structure designed to accommodate everything from dinners to performances to conferences – has popped up all over the world, from Hamburg to Liverpool. (The collective took this concept to New York in 2009 with Spacebuster, a similarly pneumatic sculpture for temporary gatherings.) In 2009, Eichbaumoper saw Raumlabor undertake the temporary transformation of a metro station into a public opera house, complete with performances scored by the rumble of passing trains and the footsteps of the local commuters. “It’s always about the people in the end – the users in a city space,” says Mayer of Raumlabor’s approach. “Space is the result of social interaction. Space is not something between walls, it’s what’s going on between these walls, and you need people to bring it to life. Space is always about negotiation.”

Emily Wong: Participation often plays a central role in Raumlabor’s projects. How important is it to involve the input of local actors and users in the design of urban space?

Christof Mayer: A lot of people don’t feel important and don’t feel like they have a voice and so one aspect is to give them a different feeling about what they can do in the city – to see what’s possible and what’s not, and what public space is about. If you are going to have long-term impact on a site, it’s important to get an idea about the perspective of the user: how do they feel about their neighbourhood, what are their needs and how do they think things could be improved? Architects often have this god-like perspective in relation to plans. The shift from this top-down view to a more experience-based view is what we try to achieve.

EW: How do you integrate the often competing interests of different stakeholders?

CM: I think it’s a different role you have then – more like a moderator or a curator. I think the crucial thing is to always be open but still focused. It’s like sailing: all the wind comes from somewhere but you have to navigate – you still have to control the ship.

EW: Raumlabor’s work seems to favour more open, dynamic processes over static masterplans. What is the value of this process in the context of designing cities?

CM: It’s always about the people. We try to encourage people to experience space and we even believe that space can be the result of social interaction. This is the ‘performative’ space of urbanism – the lived space. What are people within the city context? Are they consumers, commuters or citizens? The roles we inhabit will generate quite different experiences of our neighbourhood.

EW: Your temporary interventions in public space often operate as a form of research – a way to gather information about a site. How do testing and experimentation inform your projects?

CM: Testing is always about finding out what you haven’t known before – it’s about the possibility of discovering new things. It’s also a luxury to experiment. It’s good to learn something about a space and what works best, not just economically, but also socially. We often talk about sustainability, but this isn’t only about material things – there’s social sustainability as well. Neighbourhoods are collections of people. It’s more complex than just buying a site and developing it, then selling it off for an economic benefit. There are other forms of capital – cultural, social – in addition to the economic.

It’s a tricky, difficult thing, because when you look at temporary ventures or events you ask what impact do they have? Nowadays temporary use is also an instrument of place-making for developers. It’s become a common tool, which is okay, but you have to be aware of what you do, who it’s for and what those outcomes might be. That’s why we’ve been shifting more towards long-term projects, to think about what the long-term implications of these interventions could be. That doesn’t mean we don’t still do temporary projects, but the idea is to be aware of the long-term goal.

EW: How can architecture operate as a tool as well as an outcome?

CM: Many of our small-scale projects, for example The Kitchen Monument, bring everything together – including the outcome. The Kitchen Monument works as an architectural object, it photographs well and it works as a tool because it’s flexible and you can transport it anywhere. The idea of a tool is to trigger an interaction between people or to start a discourse within a community about what kind of development might be appropriate for a site. There are different functions. By simply placing an object somewhere strange, people will look at it and through different hospitable programming, such as common cooking and eating, it triggers conversation. But to work it needs the programming; the object alone does not work.

EW: In your Generator projects, city dwellers design and build objects that are then used to inhabit urban space in new ways. Is this about residents reclaiming ownership of their city?

CM: The Generator projects are a series of workshops revolving around making. Making is something that can create community through shared experience and communication. The workshops are also empowering in that they show people they can do things themselves. For the Sydney Generator, we wanted to make an object – not something as specific as a chair, but an abstract form that could have different configurations. With it, we tested out spatial situations and inhabited urban contexts with a kind of pop-up pavilion seating. The public provided feedback and then the police came – it was like flash mob architecture!

EW: Do you think non-designers or local residents can have significant agency in the process of city-making?

CM: I think they already have agency simply by being citizens. Not everybody has to have the expertise of a trained designer – it’s about people being more open and aware of what’s going on in their neighbourhood and about taking part in what’s available around them. This is the idea of being a citizen rather than simply a consumer. Everyone is a consumer. It’s not bad, but to reduce the way you relate to your environment to this sole function . . . well, there’s more to urban life.

EW: You mentioned that Raumlabor is starting to move away from short-term, tactical interventions in favour of strategising for a longer-term future. How is this beginning to materialise?

CM: I think the time in Berlin for this sort of interim usage is over. Previously, there was space in the middle of the city centre for it, but now it’s kind of filled up.

We’re currently working on two projects in Berlin. One is called the Coop Campus, and it’s about the development of a former cemetery. We started this project in 2014 with a garden and a school for refugees; the next step is a 240m2 greenhouse that we want to use as a lab for researching the different forms of residential buildings and as a communication platform for the information process. The other is a high-rise building complex next to Alexander Platz, which used to house the central office of statistics of the GDR. At the moment, the building is owned by the state of Germany. The initiative wants the state of Berlin to buy this property and give it to the initiative in a long-term lease, to develop the 40,000m2 building. By reprogramming this existing, empty building, we can activate different layers of urbanism by bringing different programs to a spot that otherwise could have been turned into another shopping centre or office building. Instead, we’re trying to bring in artist studios and different forms of housing for students and refugees. This is what makes it really interesting.

Both these projects again have a long-term focus. For us it has become more about securing spaces in Berlin rather than just doing something temporary. These projects will last for at least 40 or 50 years into the future.

Thanks to Christof Mayer for taking the time to chat with us. This article originally appeared in Assemble Papers Issue 7, ‘In/formation’ – find out where to pick up a (free!) copy here.