From Berlin to Melbourne: the residents shaping their cities

In recent years, more and more Melburnians have realised the value of living close to work, public transport, shops, cafes and community over simply having a backyard. Smaller households and an ageing population are also responsible for a growing desire for more diverse types of housing than the typical three-bedroom suburban home, not to mention the often prohibitive cost of detached and semi-detached houses. The ‘Australian dream’ is shifting – with many embracing more compact modes of living – but is our residential development industry keeping up with this shift? With many developers producing apartments aimed primarily at investors rather than local residents, and at larger profits at the expense of quality, true innovation can be hard to find. Many new apartments lack options for personalisation; instead they are designed on preconceived ideas about ‘what the market wants’.

In reaction to this dilemma, a number of homegrown models are surfacing that support residents to be involved in the production of their own homes. Dr Andrea Sharam of Swinburne University coined the term ‘deliberative development’ to describe the rise of community-led development in contrast with the ‘speculative development’ seen in the typical housing market. There are obvious benefits: residents are able to act as their own agents of change, resulting in greater variety, higher quality and a more affordable range of apartments that contribute to the broader fabric of the city.

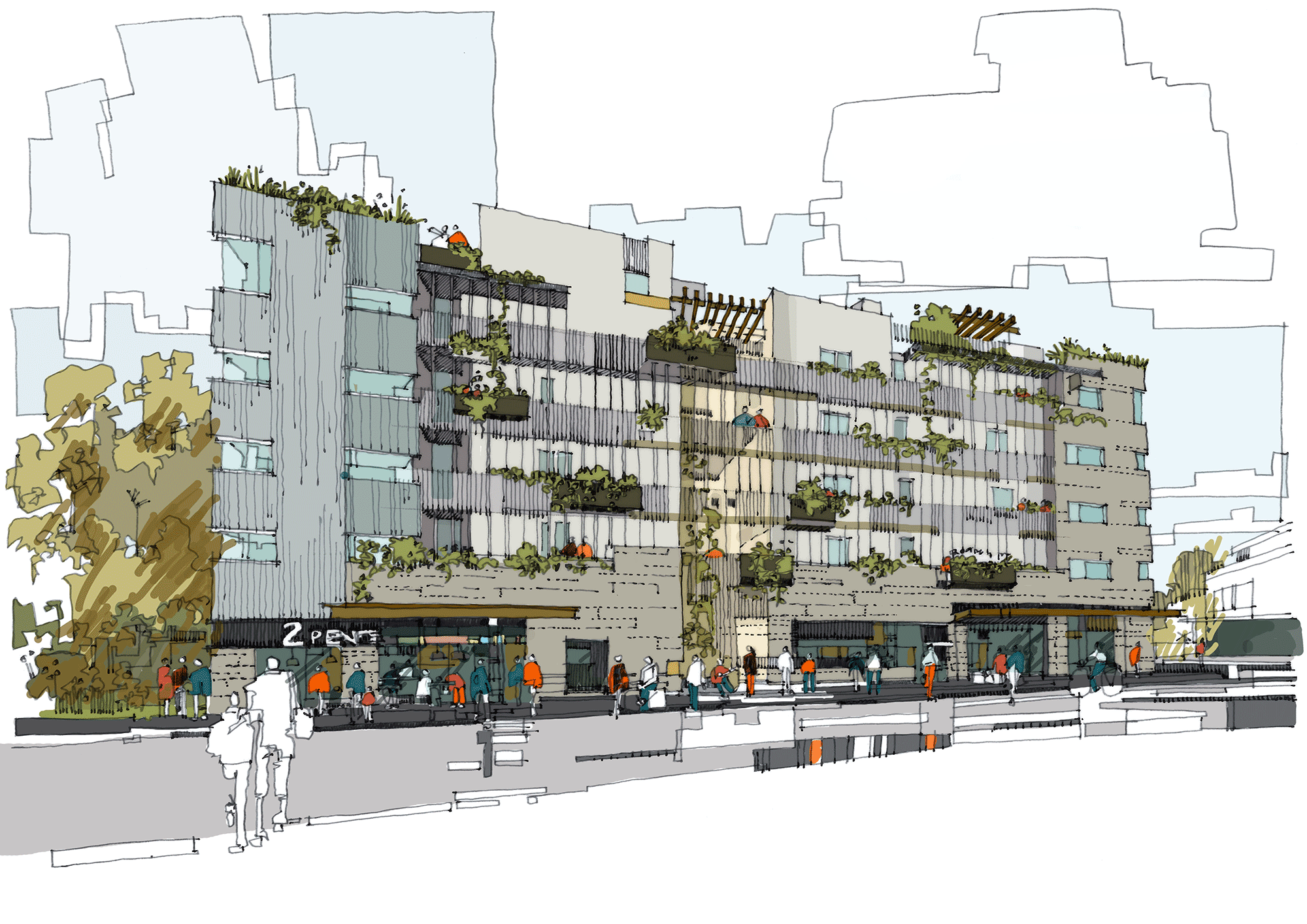

The Nightingale Model, led by Breathe Architecture founding director Jeremy McLeod, is a well-known example. Frustrated with the low-quality, expensive and unsustainable apartments the market was repeatedly delivering, McLeod decided to take on the process of developing an apartment building himself, with the help of a number of other young architecture practices. Unlike traditional development models, each Nightingale project is financed by 20 angel investors, many of them architects themselves, with each taking only the minimum profit allowed by their banks. The model ditches display suites and large-scale marketing teams, instead relying on the success of previous projects like The Commons – the award-winning, zero-car apartment building in Brunswick – to ensure the apartments sell.

In the Nightingale Model, future residents are consulted early in the development process through an online survey of their needs and preferences, such as number of bedrooms, whether they require car space and what facilities they would like to share. Money saved on typical inclusions like car parks, individual laundries and air-conditioning means apartments are more affordable and environmentally sustainable, and savings can be used for features such as natural ventilation, insulation or even rooftop gardens. Nightingale 1, designed by Breathe Architecture, is currently under construction across the road from its predecessor The Commons. Further iterations – designed by the likes of Six Degrees, Austin Maynard Architects and Clare Cousins – are planned for Fairfield and Brunswick. The early success of the model can be seen in the long waiting list of potential residents.

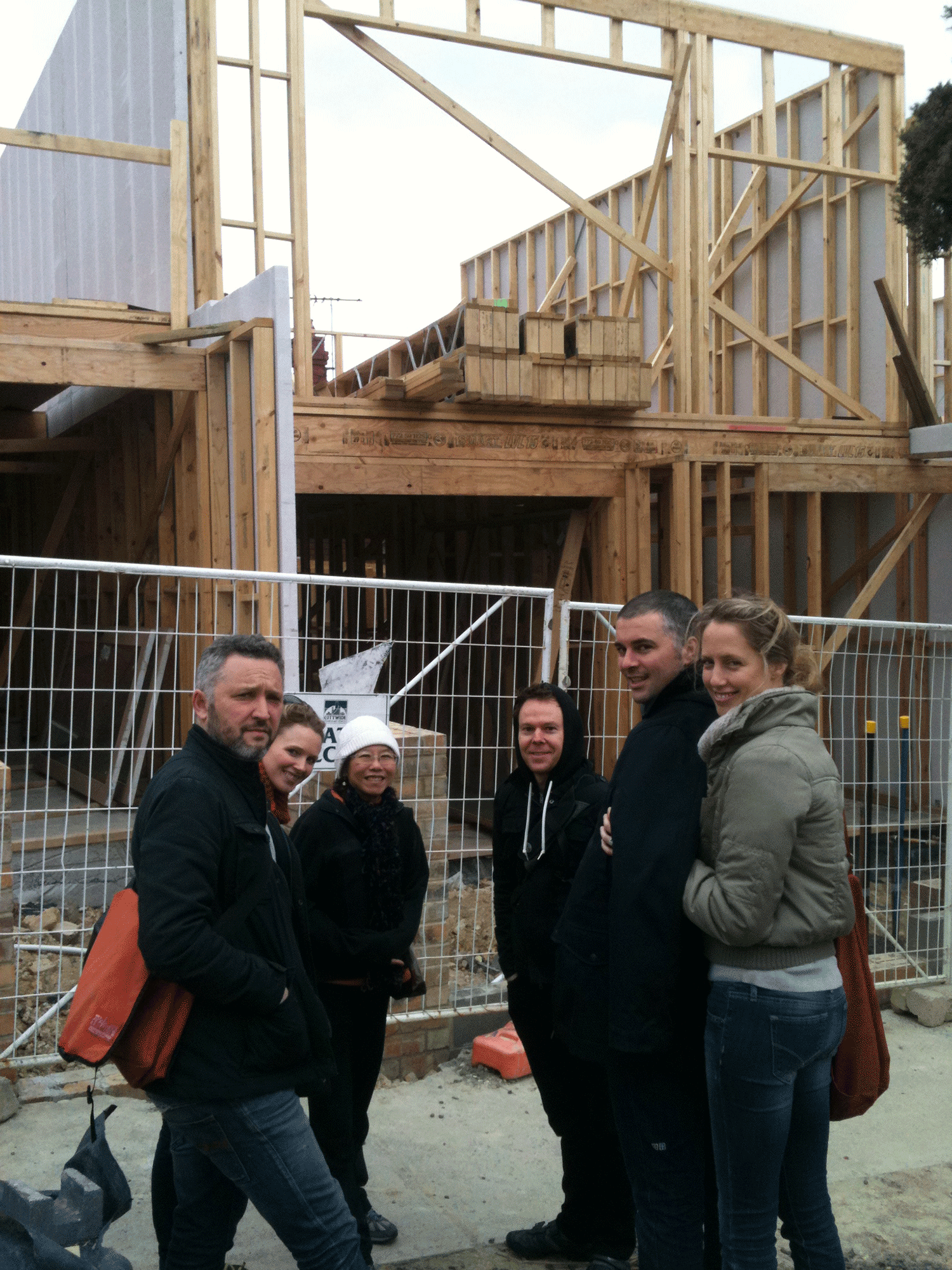

Elsewhere, Tim Riley from Melbourne co-investment initiative Property Collectives is championing another model that allows future residents even more input into the design and development of their homes. Through Property Collectives, Riley guides small groups of often first-time homeowners and investors through the process of purchasing land and jointly developing it into townhouses, in a process that sees members of the collective ultimately take on the role of the developer and become intimately involved in the design of the project. The aim is to achieve higher quality outcomes in locations where members would like to live but couldn’t afford otherwise.

This idea is not new: property syndicates have long been in existence. But purely investor-led projects can risk poor-quality results, and the complexities of finance and development can risk undermining even the most well-intentioned joint ventures. It is the mechanics of the Property Collectives model that sets it apart from others, with Riley helping to bring together groups of people with similar architectural and social values to ensure a shared goal and end result that all parties can take pride in.

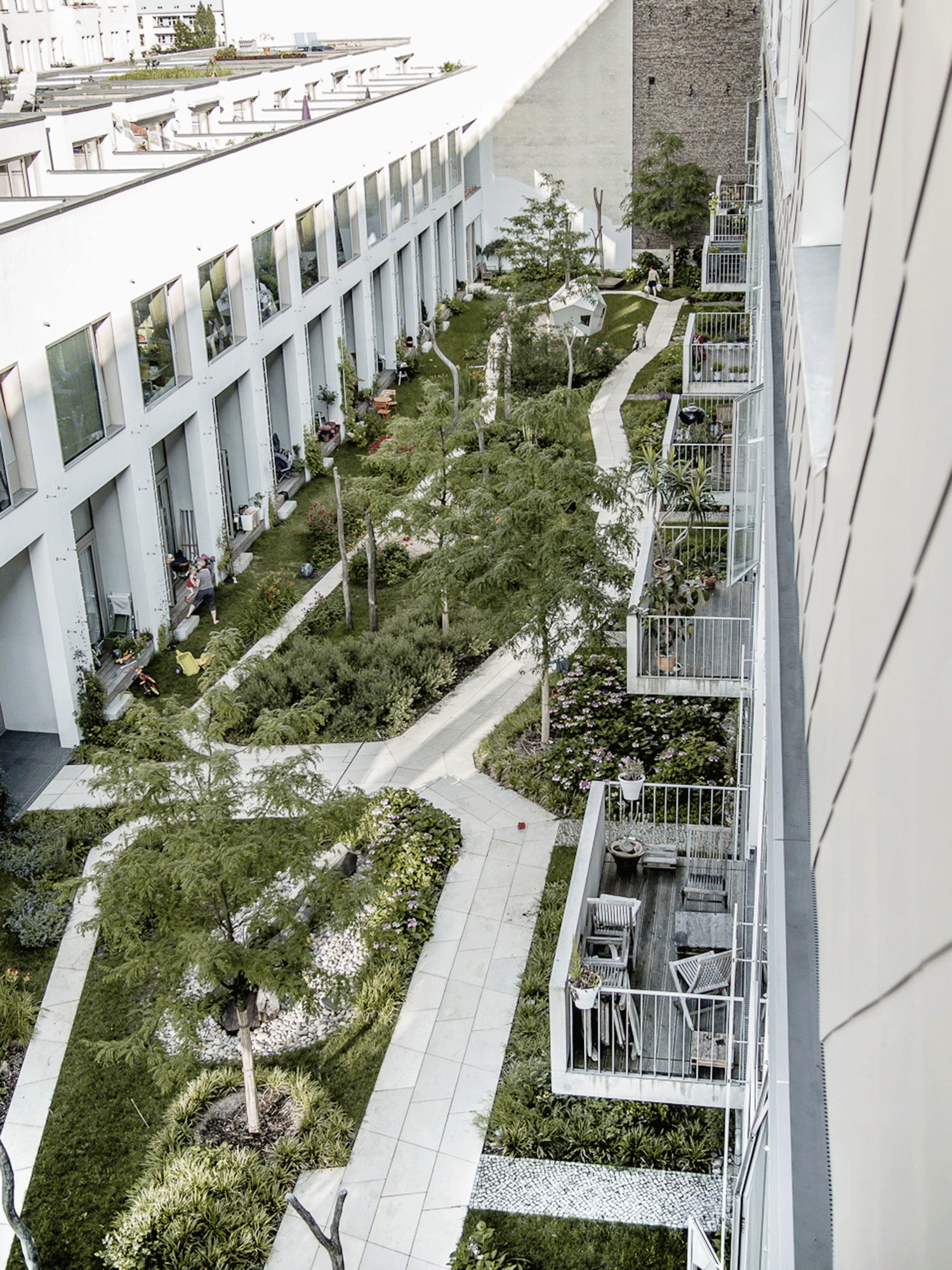

These home-grown projects share similarities with other examples of deliberative development seen elsewhere in the world, such as Baugruppen (building groups) in Germany. Based predominantly in Berlin, this model for architect-led, collectively funded and community-based living emerged in the 1990s and now contributes to a significant portion of housing in that city. Projects such as 3XGRÜN (by Atelier PK, Roedig Schop and Rozynski Sturm) and Zanderroth Architekten’s BIGyard have been able to achieve innovative design, generous spatial characteristics and shared green space that may have been difficult for a conventional developer to achieve. In looking at these examples from Australia and elsewhere, we can begin to uncover some of the benefits of this type of development:

Higher quality development

Future residents involved in the development of their own homes will preference quality design and sustainable features, unlike developers who cater primarily to profit-driven investors.

More affordable development

Outside of the traditional development framework, housing can become more affordable as future residents don’t need to make a profit on the process. (Developers generally report profits of between 15 and 30 percent on cost.) Future residents also don’t need to find buyers for the project, allowing them to skip expensive marketing costs.

Development that creates community

Collectively developed apartments open the door to a range of possibilities for shared space, like roof terraces, shared kitchens or guest apartments. Fledgling communities are fostered long before the projects are built through the social act of developing a project together based on shared values.

Development that gives back to the community

While investors aim for the highest possible space efficiency, many deliberative developments create shared green space that can even be open to the public. Residents of such developments have a greater sense of identity and belonging, which can benefit the surrounding neighbourhood.

Together with Drs Lyndall Bryant and Tom Alves, in 2015 Dr Andrea Sharam authored the paper ‘Making Apartments Affordable’, which outlined some of the ways we can further encourage these alternative models in Australia. Drawing on the ideas and processes of the sharing economy (such as Uber and Airbnb), online aggregators could encourage like-minded people to join forces in a future housing development. In having a readily accessible list of potential buyers, the risk for those initiating the development is reduced.

But developing an apartment building is a complex process that always carries innate risks. Ideally, an architect or project manager would guide residents through the process in the absence of a traditional developer. In Germany, many architects specialise in this process, providing design advice, project management and supporting collective decision-making. The next hurdle is finding finances, with banks requiring future residents to contribute 20–40 percent equity to a project – a difficult task for those on moderate incomes. With the introduction of a guarantor such as governmental or non-profit community housing organisations, these barriers could be reduced.

Deliberative development could also be encouraged through changes to current planning legislation: a cap on density in overly dense inner urban areas such as the CBD and Southbank could dampen land speculation and the saturation of investor-driven housing (the Central City Built Form review that is currently underway goes some way towards this goal). Such planning tools that restrict density would have to be introduced in tandem with new planning frameworks that encourage regeneration (and greater density) in existing neighbourhoods already well served by amenities and public transport. In allowing residents to become agents of change in their neighbourhoods – leading development instead of just opposing it – more housing could potentially be provided in areas where people would prefer to live.

Supporting forward-thinking collectives in developing their own living environment could result in quality, sustainable housing options that are accessible for a wide range of residents. In allowing participatory housing, we’re encouraging more variety and self-expression in our neighbourhoods, prioritising liveability over investment. In the book Self Made City (2013), Matthew Griffin of Berlin-based architecture studio Deadline sums it up well: “I believe the act of making the city changes your relationship to it. The more people that actively take part in creating our city, the better it will be. The city is the ultimate crowd-sourced project.”

This article first appeared in Assemble Papers Issue 6: Future Local (September 2016). Thanks to Katherine Sundermann for her expertise on and passion for deliberative development and alternative development models.

A note from our publisher: “Assemble is a residential property developer focused on small footprint projects – and the proud publisher of Assemble Papers. Our work is characterised by a people-centred design process. We engage with potential residents early on, through a series of design presentations and online surveys, and use their feedback to inform the final outcome. We support the deliberative development model, of which Property Collectives and the Nightingale model are leading examples, and advocate for a plurality of approaches to housing innovation.”

Main image: View from the top of Zanderroth Architekten’s BIGyard (2010) in Berlin, which features a variety of housing typologies, including townhouses with individual rooftop gardens. Photo: Simon Menges.