Contesting art and the right to the City with Keg de Souza and Richard Bell

“The future is already here – it’s just not evenly distributed” was the theme of the 20th Biennale of Sydney (March–June 2016). Inspired by a comment from science fiction author William Gibson, the thematic framework of the Biennale invited artists to consider the unequal power structures present in Australia and around the world, and the ways in which people are denied access to information and participation within them. The event was organised into seven distinct ‘embassies’ with an additional category of ‘in-between spaces’ in different locations around the city – it was in the latter category that some of the most memorable works were conceived. Genevieve Murray speaks to artists Keg de Souza and Richard Bell about the transformative powers of their respective ‘in-between’ artworks, both of which tackled some of Australia’s most deep-seated historic and ongoing issues of spatial and social inequality.

In Sydney’s inner-city suburb of Redfern, the area known as ‘the Block’ has long been a site of tremendous political and social significance for Sydney’s urban Aboriginal communities. With former Prime Minister Gough Whitlam providing the initial grant to the Aboriginal Housing Company (AHC) to buy homes on the land in 1973, the Block became an important site of Aboriginal self-determination and leadership.

Once a strong working-class neighbourhood, Redfern-Waterloo has increasingly found itself at the centre of aggressive redevelopment and gentrification led by the State Government. In 2004, the controversial Redfern-Waterloo Authority was established to oversee the ‘revitalisation’ of the area, before being scrapped in 2010.

The Block has also been the setting for countless acts of political resistance, from the 2004 Redfern ‘riots’ to the Redfern Aboriginal Tent Embassy (inspired by the Aboriginal Tent Embassy in Canberra in 1972), established in May 2014 by Wiradjuri elder Jenny Munro to protest the controversial commercial and residential development proposed for the site. In August 2015, Munro and the Redfern Tent Embassy lost their Supreme Court case against the AHC, though their tireless protests led to the inclusion of 62 new affordable homes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to be included in the AHC’s plans for the Block (which have their own long history of obstructions by the NSW Government). Now, the land – once dotted with campfires and clusters of people – is fenced off, awaiting the new development. When updated plans for the area were released in July 2016, Sydney Lord Mayor Clover Moore described them as “shocking”.

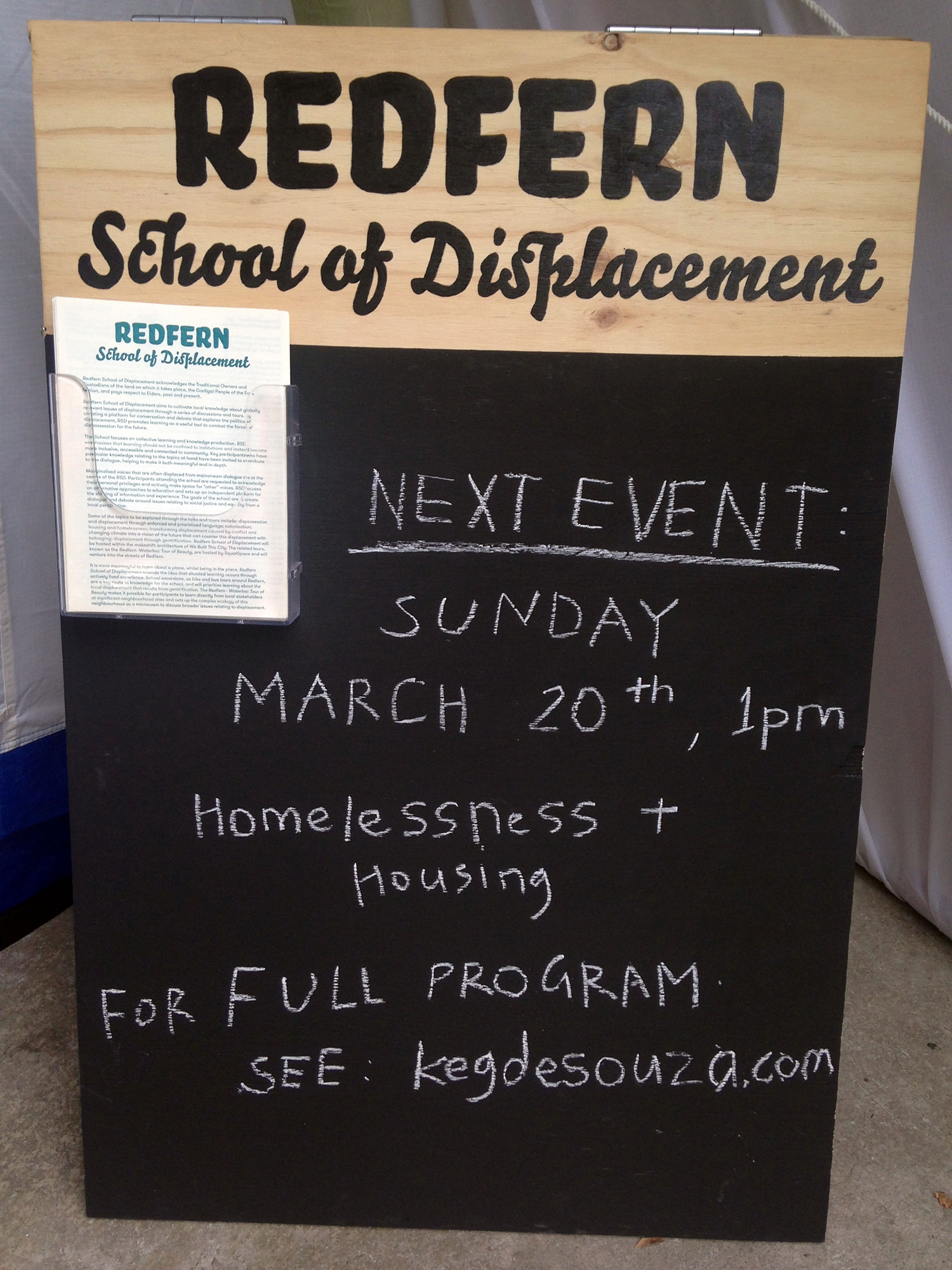

Two works in the recent 20th Biennale of Sydney used mediums of impermanence to respond to the Biennale’s theme surrounding inequality: Brisbane-based Kamilaroi artist Richard Bell’s Embassy (2013–present) – a restaging of and homage to the first Aboriginal Tent Embassy in Canberra – and Sydney artist (and longtime Redfern resident) Keg de Souza’s Redfern School of Displacement (2016). Housed inside a temporary structure made of salvaged tents (We Built This City (2016)), de Souza’s work hosted an informal ‘school’ in an attempt to cultivate space for the marginalised voices of Redfern and, like Bell’s Embassy, to create new dialogues around Australia’s ongoing history of colonisation and displacement.

I caught up with Keg at her home in Redfern – just around the corner from the park where Paul Keating made his famous Redfern speech in 1992 – and, later, with Richard over Skype. I was interested to find out how the two artists investigate the spatial politics of contested sites – Keg with her architectural background, and Richard as a passionate activist – to advocate for a more inclusive and decolonised Australia.

*

KEG DE SOUZA

Genevieve Murray: Your body of work has operated within a broad mix of social, political and cultural contexts across continents, but the Redfern School of Displacement seems personal. What does it mean to present a project of this nature in your own neighbourhood?

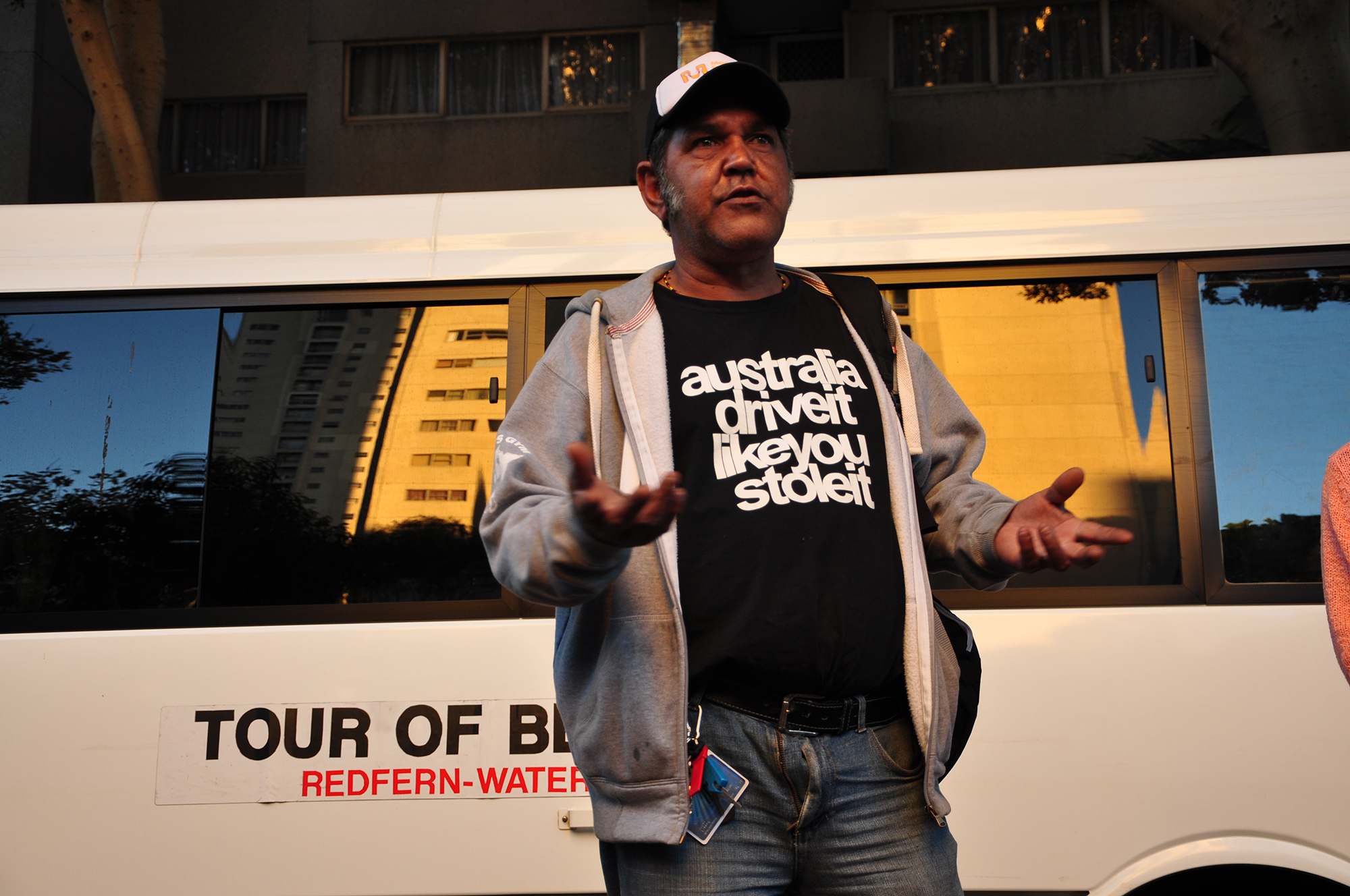

Keg de Souza: It really began over 10 years ago with another project, the Redfern-Waterloo Tour of Beauty (2005–), which we revisited with a new set of tours as part of the recent Redfern School of Displacement program. The Tour of Beauty began with a group of us working as a collective called SquatSpace. We were all living in the area and wondered about the newsletters being slipped under our door by the Redfern-Waterloo Authority. We couldn’t understand what it was. So we started meeting people around the area to try and understand the changes, such as people getting relocated out of the area and certain assets being sold off. We learned that the Redfern-Waterloo Authority was kind of a coded way of being able to gentrify the area, selling off the local hospital, the school and all these assets, which, as the area grows, are really going to be needed. So we ran these tours for five or six years, taking people on bikes and buses around Redfern to meet local stakeholders to hear their stories and it just grew. We decided the way to have the most impact would be for people to meet these residents face-to-face. Going to the different sites in the area and learning about a place while you’re inside it is so powerful: you find yourself associating the various sites you’ve visited with the people you heard telling stories about it.

Ten years on, I’m the only one left in SquatSpace who still lives in the area – everyone else has been pushed out. It’s interesting to reflect back on those years and look at what the plans are now for the area. With the Biennale project, it seemed like a good time to talk about displacement in a broader way, with the tour now able to look forward and realise that actually, these plans [for Redfern] are mega-gentrification. There’s a whole new phase about to happen and it seemed like a poignant time for this work.

GM: The Redfern School of Displacement occurs within a structure made out of recycled tent fabric, rendering an essentially simple, egalitarian material political in this context. Since the first Aboriginal Tent Embassy in Canberra in 1972, the tent has become a symbol of informality and impermanence, not to mention of refugee settlements and mass displacement in other contexts too. What is the significance of the tent in your work?

KDS: I was away from Sydney for a while and when I returned one of the first things I saw was the Tent Embassy in Redfern. It was such a powerful image seeing Indigenous people occupying their own land due to the continuous struggle to have Indigenous housing there. There were also the homeless settlements outside Central Station and the global refugee camps I was seeing everyday on the news.

The materiality of the tent is important: it’s not just about tents as protest; it’s about tents as impermanent housing that could actually become more permanent. The temporality of the structure is reconfigured into a giant communal tent where we can talk through these issues.

GM: What of your personal experience brought the issue of displacement to be a driver in the Redfern School of Displacement?

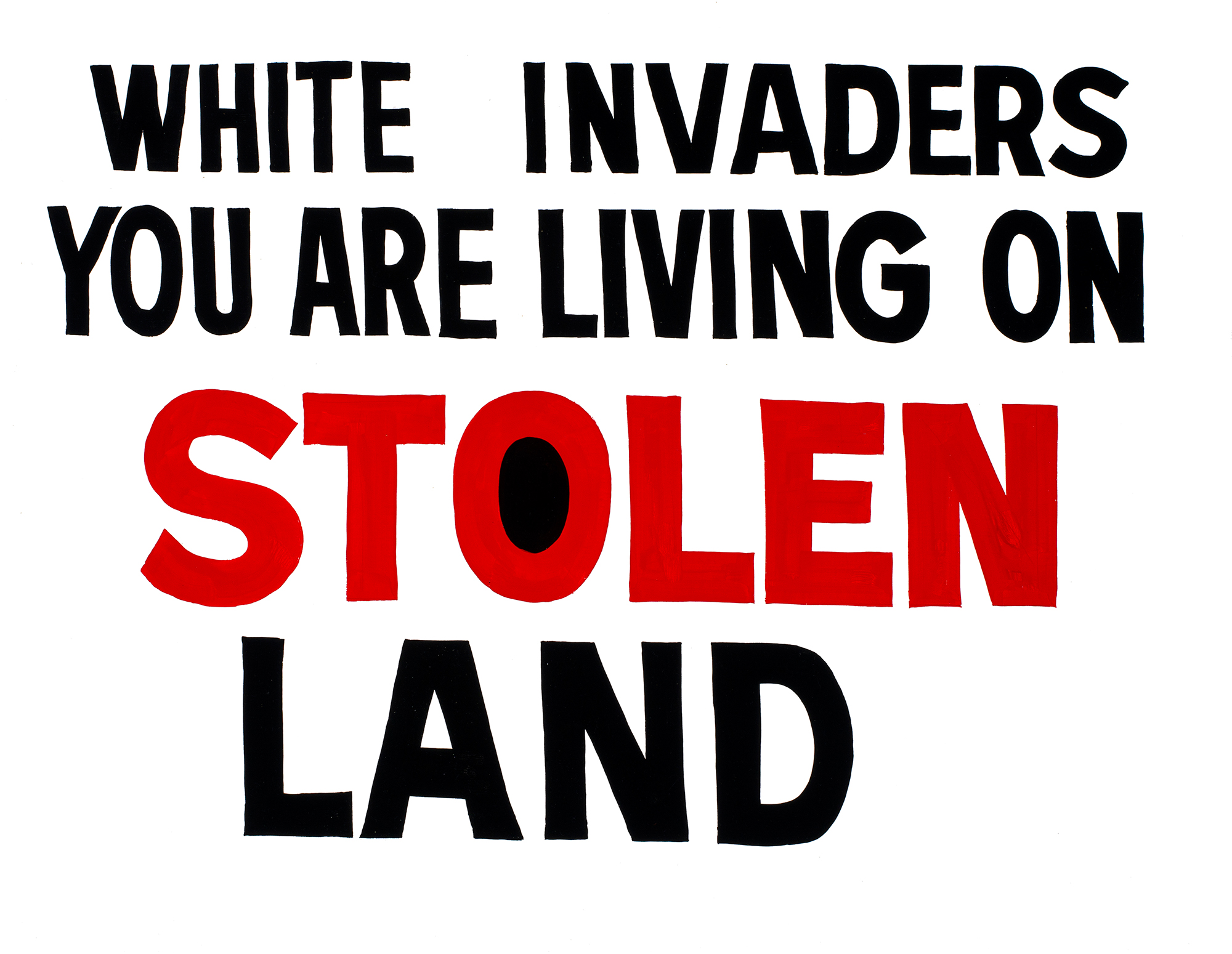

KDS: Being in Redfern, and Sydney in general, you think about being on Cadigal land. When you look at the Block, which the installation sits just behind, you’re forced to think about its significance. At the moment there’s a fence around it and it really feels like the community has been displaced, whether temporarily or more permanently. But my memories of Redfern and of the Block have always been of walking past that area [and] smelling a fire burning. It was a gathering space, and seeing that area with a fence around it makes me think about displacement and the people being shifted out.

GM: A key aspect of your work is in the making and the occupation of space. What does this bring to your work that other methods might not?

KDS: I think the temporality of the structures gives them a kind of impermanence, where it doesn’t feel like a fixed structure or that it’s going to be permanent. A lot of my past work has been inflatable, and what I’ve really found useful about creating spaces is the way they focus and transform the events and conversations happening inside them. It creates an intimate environment that’s focused on the action or the event happening inside it, rather than being about the physical structure around that temporary space.

The intimacy of the smaller, inflatable structures was useful for more intimate dialogues, but I think the larger tent structure works for bigger discussions. In the Redfern School of Displacement everyone sits on the floor or on these laundry bags – colloquially known to some as ‘refugee bags’, so quite a loaded material in itself – and everything is orientated towards the ground, so everyone is at this equal level. There’s no front or back of stage and there are no formal panels. I hoped it would help people feel more comfortable about having their voices heard in that sort of situation. These discussions look at issues of forced migration, homelessness, housing and also language as a form of displacement, and the materiality of your surroundings are so loaded that they can really shape the discussion.

GM: What do you think would give reverence to the Block and its history, and could really provide something for its community?

KDS: I don’t think it’s my place to even begin to imagine. There are so many stakeholders and so many voices, and I’m not sure there would ever be an ideal. I guess that’s something that follows throughout my practice: this idea of utopia, but failed utopias, where it’s often making these spaces but never making them ideal. I guess that’s why I didn’t follow a more architectural path – I’m interested in social space and how people shape space, and in this way the Block is so significant. This land underneath us is Cadigal land, but that particular spot has so much history. Every time I walk through it, I think about that history. It’s shameful, but it’s easy to forget these things on a daily basis. It’s so important to be reminded whose land you’re on.

*

RICHARD BELL

Genevieve Murray: What do the beach umbrella and tent structures represent for you? The genius act of utilising that informal architecture with the original Tent Embassy in 1972 as a political protest rendered an unassuming material to be potent and powerful. In ‘white Australia’ you could say the tent represents freedom, being outdoors, so I’m interested in what the tent space means to you both personally and in the context of Aboriginal rights.

Richard Bell: The reason I’ve done this project is because the idea of setting up an embassy, and a tent embassy at that, was genius! The first tent embassy was a beach umbrella, because they had no money. They arrived down in Canberra to buy a tent, they didn’t take the tent with them – they went around and tried to borrow tents from everyone they knew. One whitefella had a beach umbrella, so that became it. Both of them were loaded symbolically. I spent the first two years of my life living in a tent, so that’s significant too. There’s still people living in tents around this country.

GM: Is there something positive to be found in the tent as a domestic space? Do you find the informality and impermanence can actually provide something positive?

RB: Yes, I do. Symbolically, it’s really well thought out. Those young people who met the Black Caucus in Redfern decided they would send these young men down to Canberra and establish an embassy, and that it would be a tent embassy, which means it would be collapsible. There’s symbolism and then there’s performance art as well – there was a lot of artistic activities there to do with the banner and posters and events. You would have seen in the protests [in July 2016, against the abuse of Aboriginal children at the Don Dale Youth Detention Centre in Darwin], the women [protestors] in Melbourne constructed a cage and locked themselves in there. Performance art has always had a lot to do with Aboriginal protestors. That was another theme that I wanted to address in this work.

GM: I guess for you there’s no separation between your personal experiences and your work as an artist as an Aboriginal man within the context of the Australian art world. I think what I appreciate the most about your work is that there’s a real sense of an ‘up yours’ cheek to it.

RB: Well, we have to use the weapons and tools that we have access to, and humour and wit are a part of that. I’m lucky enough to be working in the area of art where I can say whatever the fuck I want and get away with it – but not as much as Bill Henson gets away with it. People talk about freedom of expression when they’re defending white people, but they say fuck-all when black artists get in trouble.

GM: In enacting your Embassy on the MCA forecourt, on the site of first invasion, and then inviting community from Redfern like Jenny Munro and also Gary Foley to participate – how did you find the ‘making of space’ for that conversation? What do you feel the space of the tent embassy gives to that conversation as opposed to, say, a gallery space?

RB: Obviously the position right there in Sydney Cove, where the first boats landed, is of real significance. There were these huge cruise liners parked there for 24 hours, too. They were coming and going the whole time I was there, it was really astounding. We got a lot of people from those boats dropping in to listen. Some of the tour guides were so thankful that there was this knowledge they could share that they never would have been able to elsewhere. Unfortunately, every time I do this I go in with the idea that the audience knows nothing about it. It should be getting taught in schools. There was a very famous, strange interaction between [Wiradjuri activist] Paul Coe and Gough Whitlam on the steps of Parliament [in 1972]. Whitlam came there telling the Aboriginal protestors that the Labor Party was going to deliver them from evil and all this. Coe challenged him, and said, “How can you do that? Your policy towards Aboriginal people is one of assimilation.” Whitlam asked him what he proposed, and he said, “I propose you support the policy of self-determination for the Aboriginal people,” which is quite a well-known principle in the world – the United Nations determined this [in 1960] – which generated a lot of discussion. Paul Coe convinced Gough Whitlam, one of the greatest intellects this country has produced, to support Aboriginal self-determination as policy for the Labor Party. Overnight he changed the policy of the Australian Labor Party from assimilation to self-determination. Every student in this country should know the contents of that exchange.

GM: Can you speak to the situation in Redfern-Waterloo? Keg de Souza, who you would know, did another work for the Biennale of Sydney that involved a tour of the area.

RB: Yeah, that was a really good work – great work, actually. She spoke with the local people there and got their story out, which is one of the things art can do. The tent reached into communities, and that’s what it should do. It should speak for us. There is an abomination coming there in Redfern-Waterloo. They’re going to have 70 people per square kilometre, which is three times the second-highest [population density] in Australia. The highest is over at Pyrmont, and this is going to be three times that. Not even Singapore has that kind of density – only cities like New York and Hong Kong.

GM: Do you get a sense that there’s a strong group of activists within the current young Aboriginal population? How does it compare to the 1970s, when the original tent embassy was founded?

RB: I was politicised by the Black Power movement in Redfern, and they were a small minority in the community. I don’t think there’s much difference between us and the youngsters today. I think they’re doing a fantastic job though and I’m really confident they’re making a lot of the right moves. I like the way they are leading. The Warriors of the Aboriginal Resistance have been fantastic.

Endless thanks to Keg de Souza and Richard Bell for taking the time to discuss their important works with the wonderful Genevieve Murray. For more information on the artists’ work head to the their websites, or view the 20th Biennale of Sydney 2o16 program. A special mention to the 20th Biennale of Sydney for many of the images included in this article.