Cooking Sections explores art, architecture and geopolitics through food

Daniel Fernández Pascual and Alon Schwabe’s world revolves around food – but don’t call them foodies. Hailing from Spain and Israel respectively, the pair met a few years ago at Goldsmiths, University of London’s Centre for Research Architecture (“a very peculiar place” – Daniel), where Daniel, whose background is in architecture and urban design, and Alon, who has a background in performance, went on to form Cooking Sections – a practice that enables the two spatial practitioners to use food as a tool through which to understand the world.

Defying simple categorisation, Cooking Sections’s work straddles installation, performance, mapping and video, in which the duo explores intersections between visual arts, architecture and geopolitics through the lens of food. And if that sounds like a boundless area of research, that’s because it is: Cooking Sections’s work has taken the pair to the sinkholes of the shrinking Dead Sea (Under the sea there is a hole, 2015); to the lionfish invasion of the Caribbean (Climavore, 2015); to the Spanish real estate crisis (through a paella cooking demonstration, Geopolitical Paella, 2012); and to the food network of colonial Britain in their ongoing The Empire Remains project, which all began with a politically charged historic recipe for Christmas pudding.

Recently the duo visited Sydney to take part in Fieldwork, a UTS exhibition (running until 29 April!) looking at the ways contemporary architects collect and manage information. They also stopped by Melbourne, where they presented a lecture at RMIT’s Design Hub about food, politics and space, and in particular their Empire Remains project. Sara Savage caught up with Alon and Daniel following their lecture in Melbourne.

Sara Savage: What is the motivation behind what you do?

Daniel Fernández Pascual: I guess we’ve always been interested in food in different ways, but at some point we realised it could be useful for us to use it as a tool through which to look at the world. We’re also interested in the ways in which space is constructed through different kinds of power structures, through to how people organise themselves in space, and so on. We use food as a tool to investigate.

Alon Schwabe: Food is a kind of lens for us, it’s how we approach looking at space. It’s more about how space is being constructed, and food has become a tool through which to do that. We do deviate away from it at times though.

SS: Your Empire Remains project seems to have taken you all over the world. What initially inspired that research?

DFP: It started in 2013 when we found this recipe for an ‘Empire Christmas Pudding’ from 1928 which was quite unique. It was created by the Empire Marketing Board and included ingredients from the different British colonies. That was our starting point from which to recreate the pudding, but ultimately there were more and more issues that kept coming out of it that began taking us to different places around the world.

AS: It was an interesting way to explore the postcolonial condition we live in, and the relationship London has to those places. I think also living in London and not being from the UK ourselves, it became a way for us to deal with our own presence and our roles too.

SS: You spoke a lot in your lecture about your site-specific intervention and installation Under the sea there is a hole, which saw you put on a ‘dinner’ of sorts on unstable surfaces complete (or rather, incomplete!) with holes, referencing the radical transformation of the Dead Sea and the increase in sinkholes appearing in the area. A lot of your work seems to be about fostering conversations around deeply geopolitical issues, but this particular manifestation seems like the most glaring example of that.

AS: Yes. And I think exposing knowledge is always kind of the basis of everything we do. This is done through conversation, and in Under the sea there is a hole there’s a big part where the ‘audience’ becomes the performance itself and there’s a whole layer of having to negotiate these holes in the tables, which in itself works as another way to foster this conversation.

DFP: When we did the installation and performance [at MuseumsQuartier Wien] in Vienna, people didn’t know how to deal with the ‘unstable tables’ we provided – where to sit, how to use a plate or where to put it, and even what kind of food they were eating at first glance – but lots of people told us afterwards that it created these incredible conversations with people they don’t know.

SS: I liked what you said in your lecture at RMIT about seasonality and the idea of being sensitive to the climate and environmental conditions of wherever you are in the world beyond the four seasons, like avoiding eating things like water-intensive tomatoes in California during the 2014 drought. Is this something you hope to communicate in your work, that ‘ethical consumption’ is a flexible concept and is dependent on your surroundings, as opposed to a more black-and-white concept?

AS: Yeah, we’re very much against the idea of labels like ‘fair trade’ and the conception that by buying ‘fair trade’ products you’re doing some kind of good thing for the world. I don’t think this kind of determinism really exists. Different political powers are at play that demand us to be more sophisticated in the choices we make and in the engagement we have with various products.

DFP: How do you even define ‘fair trade’? There’s no agreement in international standards; the US has one conception for ‘fair trade’ while the UN has another. When we were in Granada, we met someone who ran a farm who said that there’s a series of economic burdens for them to even apply for these sophistications. Most of the time it’s not affordable – these rules prioritise big farms over small ones – so for him it was more ‘fair’, more ‘organic’, to avoid the labels and initiate a relationship of trust with the supplier in the UK. For us these kinds of disruptions are very interesting, because it introduces a whole new logic that circumvents this kind of marketisation of ‘doing good’. We’re not saying that these labels don’t do good – some do, of course – but we’re interested in introducing this new logic.

SS: A lot of your research concerns invasive species like lionfish, which are meant to be aquarium fish but have ended up in the Atlantic Ocean, where they’ve proved to be ravenous predators that spread quickly and eat all manner of precious marine life. Can you tell me about your work surrounding invasive species?

DFP: For us it started in Cayman, with an interview with a person from the Department of Environment. He was great, kind of a mix between an activist and someone in government. Anyway, he decided because of his own interests that we need to deal with the invasion of lionfish, and he started promoting these tournaments to fish them, and also to use them in local cuisine. For us that was very revealing as an approach to ecology.

AS: I think this is really the basis of how we think about seasonality too – something that is not necessarily recurrent or cyclical but that has a different kind of timespan that can change over time.

DFP: So instead of thinking of a very fixed vegetarian diet or carnivore diet, we propose that we need to become a bit more flexible; we might need to eat lionfish for three years until the problem is solved. That constitutes for us a new approach to seasons, precisely because of all these disruptions in the environment caused by urbanisation forces. We’re actually doing another similar project that we’ll launch in Glasgow in April, this time dealing with a different kind of invasive species, the Japanese knotweed. We talked to different botanists and they say that yes, Japanese knotweed is spreading everywhere, but it has been doing so for over 100 years. All of a sudden though it’s become a threat to real estate; you may not even get a mortgage if you have this plant in your garden over there.

AS: In the UK, if you have Japanese knotweed, you’re not able to sell your house.

DFP: What we’re looking at is how this image of fear penetrates through real estate and the circulation of property value…

AS: …and we’re using ice cream parlours in Glasgow as a site! Ice cream was the thing that was imported into Glasgow at the beginning of the 20th century with the Italian migration into the city and into Scotland at large, and it sort of became an important tradition and even a part of the urban landscape. So we’re using these parlours as a place to question what is native and what is invasive, or how the invasive could be turned into native. That’s actually the title of the project, The next ‘invasive’ is ‘native’, and basically we’re making ice cream out of invasive species within cafes.

AS: I think with Climavore (2015) there’s a lot of questions about the future of these things, and how you understand and approach them as we step into an era of climate change and into a place where human actions and natural phenomena can’t be separated anymore.

DFP: With the ice cream project, we’re talking to ice cream parlours and the idea is that if people start demanding it, perhaps it will create enough of a demand to sell the ice cream in the months that follow. In that sense we hope to initiate something that continues into the future.

SS: You’re currently working on an Empire Remains shop in London. What will that entail?

DFP: We call it a ‘shop’, which is a bit of a funny name, but we like it because it connects to these Empire shops that never opened in the 1920s, and that came as part of this propaganda board. What we’re trying to do is I guess a contemporary version of that from a critical perspective of those same shops today – that’s why we call it the Empire ‘Remains’ shop. It will be more of an installation space to think about what currency means today, what is value, and how do we reimagine all these visions or landscapes after most of these overseas territories manage to become independent? So that’ll take the form of things on display but also more ephemeral interventions. It will hopefully open in the [European] summer.

Thanks to Alon and Daniel for taking the time to chat with us during their busy time in Melbourne. Thanks also to Timothy Moore and our friends at SIBLING for facilitating the Cooking Sections lecture at RMIT, and for connecting us with Alon and Daniel. To find out more about the ongoing work of Cooking Sections, visit cooking-sections.com.

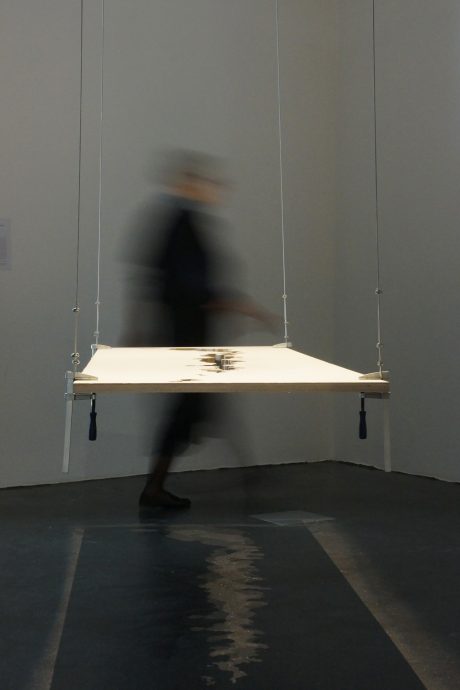

Main image: Cases of Confusion (2015), courtesy Cooking Sections.