AL_A creates otherworldly architecture

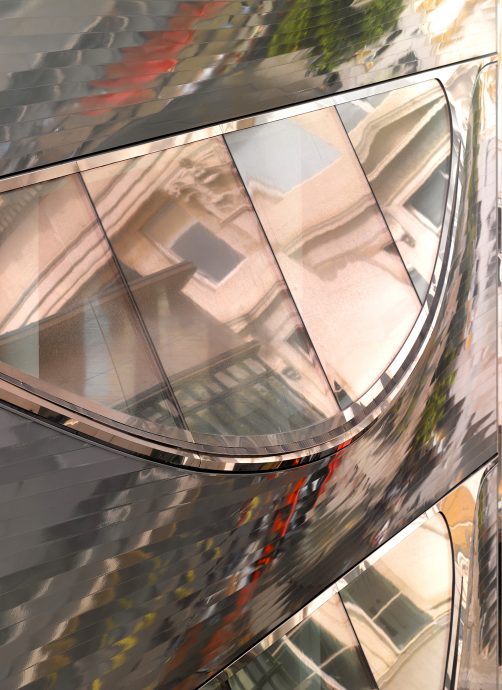

The building’s façade is liquid silver, a startling contrast to the period masonry that surrounds it in the narrow laneway just off London’s Oxford Street. Seen obliquely, something curvaceously muscular, too, appears to be pressing out against its surface. Four distinct swellings ripple the seven-storey façade, reaching up to the cold light of London’s sky. For those tottering across the laneway’s mouth, beneath bags full of the latest high street fashions, it must be a vaguely unsettling experience, this peripheral glimpse: a brief vision of a world where a building follows the laws of a kind of fleshy phototropism – part animal, part vegetable, part machine.

The 10 Hills Place office building encapsulates perfectly the ethos and obsessions of AL_A, the practice formed by Amanda Levete in 2009 after she split away from architectural avant-gardists Future Systems. As Levete said at the Australian Institute of Architects National Conference, where she presented earlier this year, AL_A’s work is always the outcome of a balance between form and function – a play on a conventional architectural sentiment, first expressed by the American architect Louis Sullivan nearly 120 years ago, but one which in AL_A’s case is tempered by a ready willingness, or even desire, to break with conventions of form and construction.

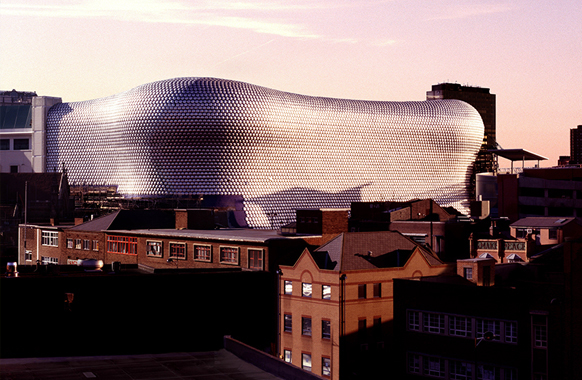

A product of intense constraint, 10 Hills Place transcends the banality of its setting and typology to become otherworldly – yet it is an outcome arrived at in part by very pragmatic considerations around daylight penetration into the building. Those bumps are an ingenious means of pinching a little airspace from the laneway to scoop in extra light from above, despite the tall buildings pressing in on all sides. AL_A achieved 10 Hills Place’s uncanny form using a tongue-and-groove system of aluminium profiles more commonly found in boat building. Since completing Hills Place, AL_A has gone on to apply its sensibility to a prestigious commission to alter and extend the V&A Museum (due for completion in 2017), one of the most significant cultural institutions in Britain, and in the 1.5 million square foot Central Embassy shopping centre and hotel in Bangkok, Thailand, among other high profile projects.

Very shortly, Melbourne will also play host to its own AL_A project: the 2015 MPavilion, the second temporary architectural structure in the Naomi Milgrom Foundation’s series to grace the Queen Victoria Gardens over the summer period. The prospect of an AL_A MPavilion is an intriguing one. The MPavilion program is modelled on London’s Serpentine Pavilion, which every northern summer sees a highly regarded architect construct a temporary structure in London’s Kensington Gardens. The temporary nature of the commission and the relatively undefined program for the building allows great leeway for experimentation. Within AL_A, the drive to experiment is innate, so this aspect of the legacy will suit it well. As what is essentially a commission for a folly, though, it’s less clear how AL_A will reconcile its adherence to the dictum of form balancing with function given such an open brief.

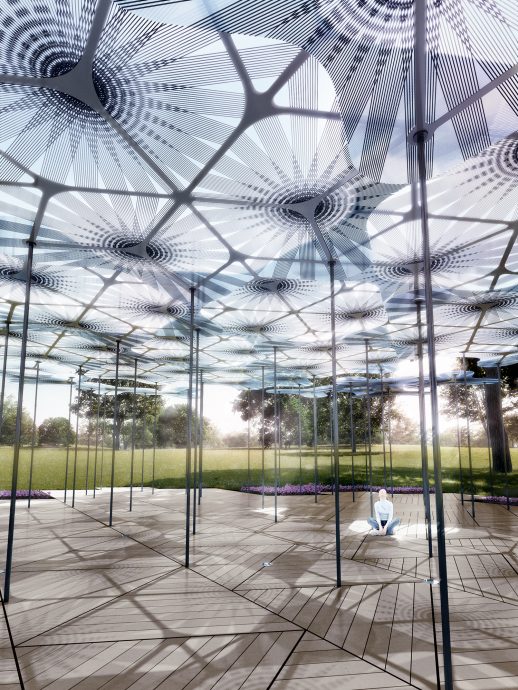

A pavilion commission of this nature is perhaps the closest architecture ever gets to sculpture, because it is so unconstrained. Over a patchy Skype connection to London, I put this to Levete. “I always resist the analogy of sculpture – I think the sensibility of an architect is completely different to that of an artist,” she says. “But when you do something in the middle of a park, which is our site, you’ve kind of hit it – as architects we need resistance, we need constraints, it’s when we’re at our best. It’s much more difficult when you have a greenfield site.” To circumvent this problem, AL_A in effect synthesised its own constraints. In keeping with the practice’s interests, these took the form of technological questions that test our assumptions about the appropriate characteristics for a building – both its material and its behaviour. “For me, the big opportunity was to do something that challenged the norm for buildings, to make a structure that in some way responded to the weather, that moved very gently in the breeze,” says Levete. “We wanted to create the sensation of a tree canopy, with beautiful dappled light where you can see the sun, you can see the sky – a dreamy atmosphere. Then the question became how to create that.”

The roof of AL_A’s pavilion will be comprised of vanishingly thin, translucent petals up to five metres in diameter but only three millimetres thick. Slender 40mm wide columns, made from carbon fibre tubes developed for camera tripods, will form the supports. At night, hidden LEDs will light the petals from within. To build this dramatically dematerialised structure, AL_A is working collaboratively with mouldCAM, a marine fabrication specialist, and the Australian office of engineering firm ARUP. Together, the team has developed a composite that combines a clear resin used for surfboards with carbon fibre strands, to achieve both translucency, and the flexibility and strength needed for the petals’ five metre spans. Much like 10 Hills Place, then, AL_A’s MPavilion will be a strange hybrid of high technology and organic form. It too, will prompt curiosity, drawing attention to both itself and an otherwise oft-overlooked part of the city, in this case Victoria Gardens.

In service of the idea of the pavilion as a tree canopy, or as a building that responds dynamically to the climate, though, AL_A has made a brave move: the pavilion will have no walls. Given Melbourne’s fickle weather, this commitment to conceptual purity is risky, as unlike the Serpentine, the MPavilion initiative is not only an architectural commission, but an extended program of cultural events, most of which are hosted within the pavilion itself. Its testament to the Naomi Milgrom Foundation’s dedication to the experimental potential of the commission that it is prepared to support this decision. It also plays directly to the inherent tension in these kinds of commissions between art practice and architecture practice. With a straitened capacity to serve its program, and even to serve as shelter, how will it function as architecture? There is an apparent tension here too, of course, with AL_A’s own ethos, where form is always bound by function. But then, we could also argue that this is latent in the practice’s output already, perhaps even what drives its most productive work.

As Levete put it in her presentation at the AIA conference, quoting the poet WH Auden: “by being merely pragmatic, by using only rational thought, desperate to know whether what we do is right, we destroy the very basis by which the good or noble things in life exist.” Rain or shine, what will it actually feel like to wander beneath the canopy of AL_A’s MPavilion? Will it bring reverie or discomfort? Will it be an unsettling beauty or a picturesque folly? For now, judgment remains deliciously resistant to rationalisation. Levete and her team are taking a small but potent step into the unknown.

MPavilion launches its 2015 commission in Queen Victoria Gardens, Melbourne, by AL_A on 5 October, with a jam-packed calendar of free cultural events every day over summer, 5 October 2015 – 7 February 2016. Visit for a talk, a sunset ritual, or a workshop – and pick up a copy of our latest print edition, themed ‘The Architecture of Wellbeing’, a special issue to mark the unveiling of AL_A’s MPavilion. Visit mpavilion.org for a full listing of events, or for more information on the work of Amanda Levete and AL_A, head to: ala.uk.com