Inkster Maken: history and prehistory

Hugh Altschwager is a designer with a deep connection to the materials of his craft. His first range of products under his brand Inkster Maken – a nod to his Nordic background, taken from his mother’s maiden name and the Dutch verb ‘to make’ – is a series of hanging pendants and wall-mounted orbs made from hand-lathed South Australian limestone and reclaimed Australian hardwoods. Though designed and made in Melbourne, where Hugh now lives, the products are artifacts of a childhood spent creating and building on his family’s farm in Tantanoola, on South Australia’s Limestone Coast.

The Limestone Coast is a newly coined term for the southeast South Australian region bordering Victoria – from the mouth of the Murray in the Cooyong National Park, all the way to the Glenelg River in the east. Mount Gambier – home of the Blue Lake – is its major civic hub, where the population is barely pushing 25K. The region is riddled with underground caves and volcanic craters, and aptly named for its deep limestone deposits – a relic of a prehistoric seabed that used to creep much further inland.

When I was 13 I moved to Mount Gambier from a much larger town in the bitter north of England. It was a stark contrast to where I’d grown up, and it took me a long time to get used to my new home – the smell of wood chips that followed you everywhere, the plumes of smoke from saw mills dotted on the horizon, a main street you could walk the length of before it began to disappear into farmland. The skyline was a mass of glistening or (gracefully) greying limestone, with many of the buildings in the area made from huge slabs of the sedimentary rock.

Hugh and I were in the same year at school and we had a few months overlap before he left to board in Adelaide. It was long enough for his name to stick in my mind, so when I came across his work nearly fifteen years later (mind blown) I immediately tracked him down for this article. We caught up for a coffee so I could learn more about the Inkster Maken chronology (while photographer Chris Von Menge visited Hugh’s Toorak workshop a little further down the track).

Hugh’s rural upbringing is an integral part of his practice, and so naturally it’s where our conversation begins. Reflecting back on his childhood, Hugh says, “I think having the freedom of growing up on a farm – being able to always make things and use your hands and just work things out for yourself – that’s where the passion came from originally. I was always building things when I was growing up – without even realising it I was developing skills and learning to work with different materials.”

To me, Mount Gambier felt like the sticks, but the Altschwager farm is far more remote. Hugh says, “it was that isolation from other influences that helped me build a sense of creativity, and I often think about how important that was. Because especially now, your mind gets so flooded with other resources and things that are always in your face, it’s hard to have an original thought. I remember when I was a kid, a lot of the time there was no precedent for what I was doing – I just did whatever came into my head.”

After finishing school, Hugh first studied winemaking, seeking a creative profession that maintained his connection to the land. After discovering it wasn’t for him, he moved into architecture, finishing the undergraduate component of the degree and then working in construction management for several years. “Looking back, I wish I’d stuck with architecture, but I don’t know if that would have necessarily changed where I am now. I still think I would have ended up working with my hands and making my own products.”

In every uni break, Hugh would come home and work on the family farm. He spent his spare time salvaging and collecting materials from around the property, and little by little (over five or six years) he used what he could find to build a small hut (or hutte) overlooking the ocean. When it came to lighting the space, Hugh started to experiment with the limestone he found lying around.

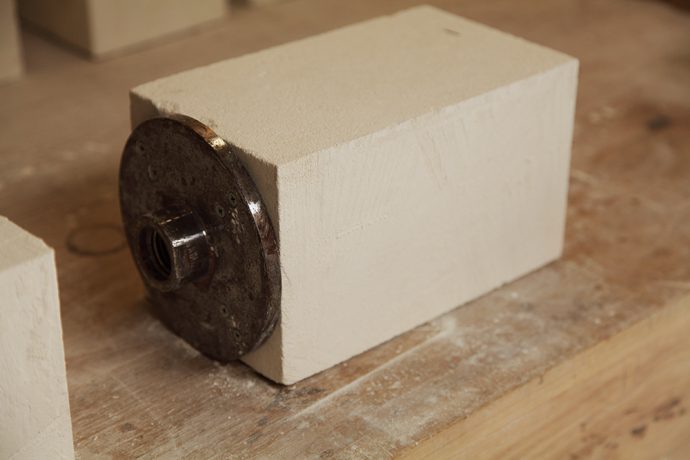

Limestone is so prolific where Hugh and I grew up, at first I thought that’s just what Australian houses were made out of – but it’s not widely used elsewhere. Hugh says, “I’d always played around with timber and limestone, but it wasn’t until I was older that I realised not many people had a connection with limestone or had even seen it used.” It’s is an incredible material to work with – surprisingly soft, with a beautiful natural grain that is the result of millions of years of sedimentary formation.

Buildings made from limestone allude to their fine craftsmanship (a dying trade), and tend to get better with age. Here in Melbourne, John and Sunday Reed used Mount Gambier limestone to construct their modernist home (and now museum) Heide II in 1964, briefing the architects McGlashan & Everist that the building “should be romantic, have a sense of mystery and weather over time to take on the appearance of a ruin in the landscape.”

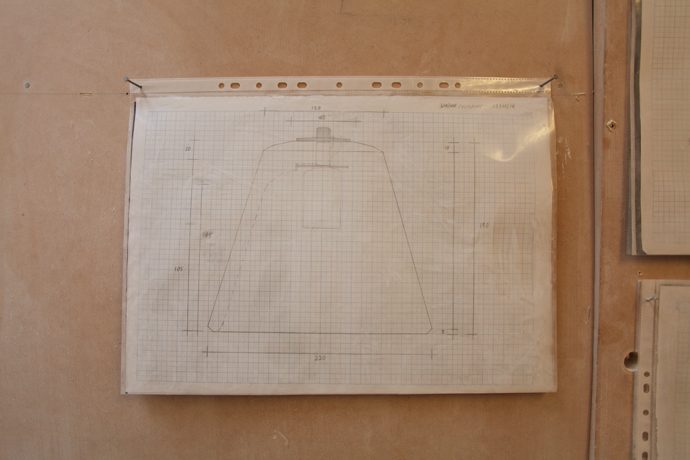

Hugh’s light for the Hutte (which the Inkster Maken pendants are descendants of) was hand-carved from a block of limestone using only a chisel and a rasp. “It was quite time-consuming. I remember being really happy with the product but thinking to myself: there’s no way you’d ever turn this into a thing because it’s so laborious.”

Hugh let the idea percolate in the back of his mind for six months and it returned to the fore after he moved to Melbourne. He’d had a breakthrough: “One day I went and bought an old woodworking lathe – I figured out a process that allows you to get the limestone onto the lathe so it turns the stone and you can actually work it.” It took another year for Hugh to get the process down, treat the stone to get the finish he wanted, and develop his first designs. Then, after all his years of tinkering, Hugh launched Inkster Maken in 2013.

Though Inkster Maken has only been in existence for the past 18 months, Hugh has already gained a lot of ground in the industry, and recently he’s been able to leave the construction management behind altogether. The current range includes four pendants (Inkster, Flashlight, Funnel and Factory) and the Eclipse Wall Light. Between them, they’ve illuminated the likes of Fonda Mexican, The Hungry Workshop and Jardin Tan here in Melbourne, as well as many other venues both locally and beyond. The Flashlight Pendant travelled to the London Design Festival in 2013 and Hugh shared his story as part the Asahi Silver Sessions held at Andrew McConnell’s Supernormal earlier this year.

I asked Hugh what he hopes for the future of his craft, and he explained, “I have found myself in the position where I am busy creating and selling my own designs which, if you asked me last year would’ve been a dream come true. However, I feel that as I begin to realise a few of my goals, it provides the inspiration to keep pushing things further and aiming higher. Ideally I want to find ways to free up my time a little so I can continue to work on new projects, products and ideas. Everything that has happened to me in my life has led me to this point. I want to keep drawing inspiration from my background and direct that energy into growing Inkster organically, slowly building on the brand and philosophy I have started.”

Huge thanks to Hugh for taking time out from the workshop to chat to us. Inkster Maken products are available for purchase on his website, and Hugh will be launching a new range there next year. All photos were taken by Chris Von Menge. In recent news, some of Chris’ work will be featured in a forthcoming book about the Bakehouse Art Project, published by Black Inc. Books.