Age of Enlightenment: cafe culture

Cafés have played an important role in the enrichment of the world’s most cosmopolitan cities since their emergence from the Ottoman Empire in the 17th century. Writer and caffeine drinker Anna Hickey explores the impact of the humble bean on the proliferation of culture, now and then. While empires have risen and fallen and societies evolved, the essence of the coffee house – a space for egalitarian social exchange – remains strong.

If you were to enter a European coffee house in the 17th century, you might have stumbled across scientists, artists and philosophers, swapping ideas while sipping Ethiopian coffee. This was a time of scientific and philosophical discovery (think Isaac Newton and Descartes), with caffeine no doubt stimulating the grey matter of great thinkers of the time. These coffee houses often catered to niche interests, such as politics and philosophy, offering libraries of books, newspapers and pamphlets on specific topics. Picture the cultural leaders of yesteryear nestling themselves into the corners of a café for a good read.

Fast forward to the coffee shops of today – people enter hailing from different places, yet seeking the same nourishment, comfort and sense of belonging from the one space. Like Europe in the 1600s, everyday and important ideas, conversations and decisions happen in coffee shops daily. While there is always vast room for improvement (safer cycling, better public transport and infrastructure), Melbourne (awarded the world’s most liveable city by The Economist Intelligence Unit Survey) is an exemplar of the impact and cultural enrichment of coffee houses on the urban fabric. Cafés play a leading role in our cityscape. According to the City of Melbourne, there are now over 2,190 cafés and restaurants and over 166,000 café seats in the central business district alone.

Coffee arrived in Australia with the First Fleet and according to Museum Victoria, the café scene in Melbourne started in the 1890s. Inspired by their European origins, the original Melbourne cafés took on names such as Vienna Café and Café Denat (where iconic Melbourne restaurant Grossi Florentino now resides). Coffee houses really started to boom in Melbourne during the Temperance movement of the 1930s, when community members were encouraged to substitute alcohol for coffee, instead visiting coffee lounges for ritualistic caffeine-fuelled social gatherings.

The inception of institutions like Marios (established in the 1980s) and Pellegrini’s Espresso Bar (set up by Italian immigrants in the 1950s) – and the introduction of espresso machines – really planted the seeds for the now booming Melbourne coffee culture. Local government even recognised the important role cafés play in bolstering community. After the recession in the early 1990s, the government included coffee houses in policy as a tactic to breathe new life into the city of Melbourne. The fact that Melbourne hosted the 2013 International Coffee Expo with over 7000 local and international visitors highlights the important cultural role that coffee and cafés continue to play.

For many urban dwellers, the coffee shop experience is embedded in ritual. During the week, office workers gather with colleagues and catch-up while ordering their take away lattes. Freelancers, entrepreneurs and uni students set-up shop for hours with their laptops over an espresso or three. Tourists find familiarity, free WiFi and the promise of a ‘third place’, home-away-from-home, in global coffee chains scattered throughout cities.

Bowen Holden is the proprietor of one of Melbourne’s most popular cafés, Patricia, which is located in the heart of the city’s legal district. On any given working day you will find the compact, standing-room only café crowded with a variety of customers eager to make Patricia part of their day. “Where we are located, we get a lot of barristers, lawyers and judges coming in for coffee. We have bankers as well and people journeying to the city especially for coffee. So it’s a really interesting mix. Our café has got a feeling of activity about it. There are lots of catch-ups and you do hear a lot of business go down. There is a general feeling that things are happening around here,” said Bowen.

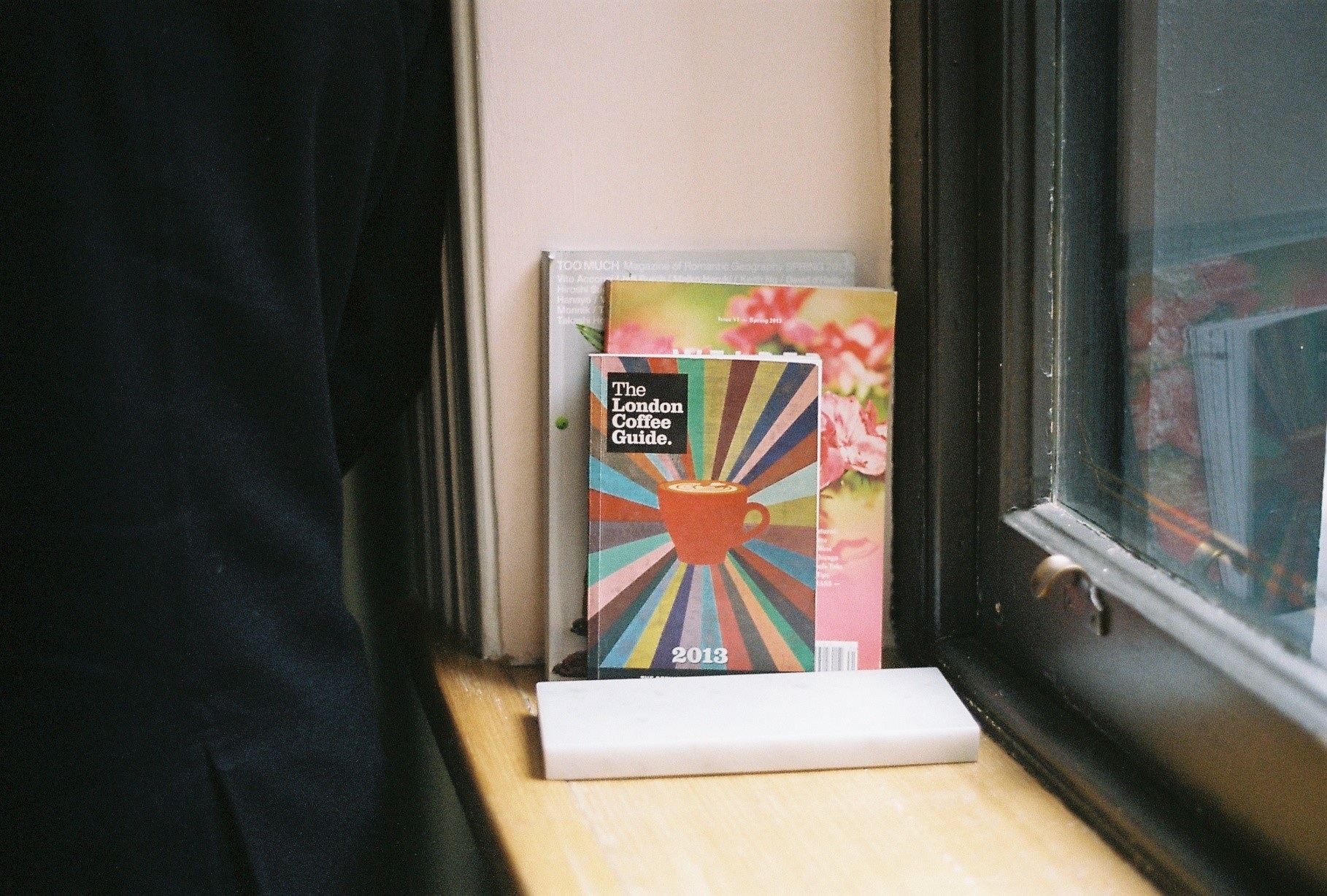

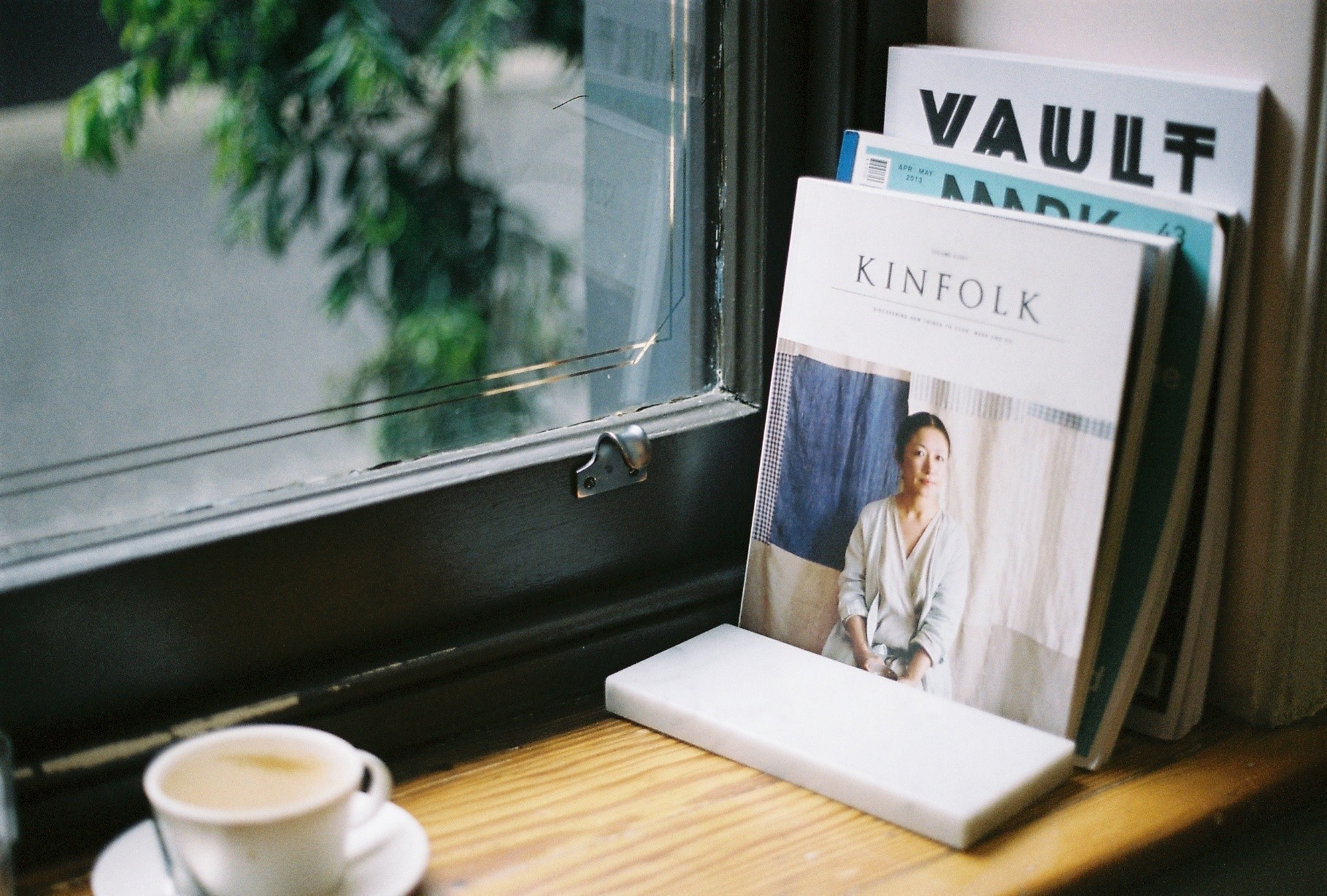

A striking element of Patricia is the aesthetic of its physical space, designed by Melbourne/Sydney-based practice Foolscap. Three large boards fill up an entire wall of the café where newspapers are pinned daily and a small library of niche magazines are displayed along the sunlit windowsill. According to Bowen, balance and inclusion are important parts of the café’s philosophy; the magazines and newspapers help to make customers feel welcome. “We are refined as far as what we offer, by only serving coffee, but we don’t want to exclude anyone by doing this. All of our magazines are hand-selected by someone who runs her own magazine and they are all very design driven and fashion orientated. We want Patricia to be about everyone. Even if they aren’t into coffee, I hope it is a space where people just want to come,” said Bowen.

Patricia is not alone in its measured decision to specialise in coffee (you won’t find tea or hot chocolate on their menu). Coffee has always played a central and critical role for cafés as their driving force. The beverage that first became popular in Islamic communities as an alternative to alcohol has become the catalyst for gatherings around the globe. Since coffee entered Europe via the Ottoman Empire in the early 17th century, and the first coffee house opened in Venice in 1683, the humble brown bean has brought people together, enlivening Western culture. While the world has evolved, the pace of life has quickened and technology has embedded itself in everyday life, people still flock to cafés to meet and discuss knowledge and ideas – to ponder what is possible.

KereKere, a leader in the current movement of social entrepreneurial cafés, opened its first coffee cart at The University of Melbourne in 2007. The concept of KereKere (which means giving without expectation in Fijian) revolves around linking the traditional café experience with social justice and sustainability issues. The staff at KereKere comprise young people who have experienced difficulty finding employment due to various life challenges. Customers are encouraged to play an active role in sustainability and social issues: with a coffee purchase, customers receive a playing card with which they can choose to donate proceeds to a cause across the arts, environment or health. As a leading Australian university, home to globally-renowned thinkers, The University of Melbourne was the ideal location for KereKere proprietor James Murphy to open his progressive café.

“I remember that I thought this is only going to work at Melbourne University – for what I want to do. We were a café, but first and foremost a vision. We have since learnt to engage a broader audience,” said James. Like the coffee house proprietors in Oxford, James’ hunch proved right, and the support of the university community enabled KereKere to develop from a coffee cart to a spacious coffee house in the Boyd Community Hub in Southbank. Like the philosophers and political thinkers of yesteryear, KereKere is utilising a shared space to create bigger social movements. “The core of what we do is that we like to be part of something bigger than us. At the Boyd, we really feel part of the community. We like to be part of a broader community – we play that role”, said James.

The progressive initiatives taking place in Melbourne cafes are as much embedded in the notion of social exchange and history as they are caffeine. A number of contemporary cafés in Melbourne pay homage to the symbolic history of caffeine. Take Seven Seeds coffee roasters in Melbourne for example. One of their most popular cafés, Brother Baba Budan, is named after an Islamic scholar who smuggled seven seeds of coffee out of Yemen during the 16th century, eventually planting them in southern India. This triggered the global expansion of the coffee industry; wresting the Ottoman Turks’ stronghold on coffee trade. Or consider the St Ali Sensory Labs. Through a distinctly scientific approach, St Ali pays homage to caffeine’s original use as a medicinal and religious aid by Islamic communities.

Historical references aside, Bowen from Patricia perfectly sums up why the café experience embodies community and cultural enrichment. “I personally get a lot out of something that is made really well and with care. That in itself gives me a pleasure reaction. It’s the ritual – the routine, of coffee. Coffee helps to develop a sense of who you are”.

Many thanks to Bowen Holden and the team at Patricia Coffee Brewers (93-495 Little Bourke St Melbourne VIC 3000) and James Murphy at KereKere (207 City Rd Southbank VIC 3006). For a serve of tradition, try Pellegrini’s (66 Bourke St Melbourne VIC 3000) and Grossi Florentino (80 Bourke St Melbourne 3000). The history of coffee is complex and fascinating – Mark Prendergast’s book Uncommon Grounds provides a thorough overview. All photos snapped by the excellent lens of Nusha Gurusinghe.