Timeless and puzzling: Enzo Mari

The design work of Enzo Mari, iconic Italian provocateur and octogenarian, is often described as elegant, minimal and functional. Grace McQuilten prefers to think of Mari’s work as puzzling, playful and human. Here she looks back at ‘autoprogettazione’, Mari’s range of DIY furniture and a beguiling body of work that defies mass production and the march of time.

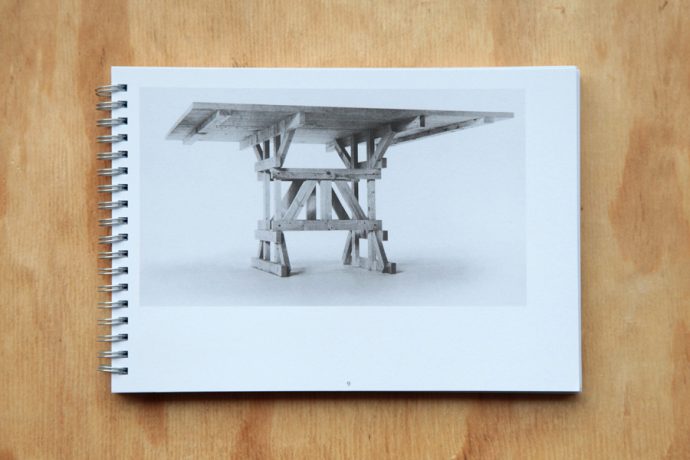

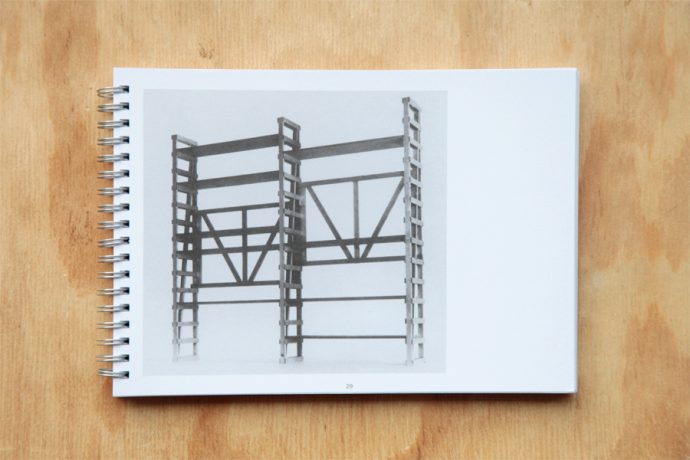

Enzo Mari’s autoprogettazione chair is constructed from pieces of pine, all of the same width and thickness, cut into various lengths and pieced together to make a simple yet very solid piece of furniture. An incredible symmetry is created through the use of only one material, which also makes the chair easy to construct with zero waste. Anything additional to its purest function has been removed. Despite this apparent minimalism and functionality, the finished product has an individual character, a hand-made craftiness and a uniqueness that speaks of Mari’s quirky design spirit. The chair is part of Mari’s larger autoprogettazione (originally published in 1974, with a recent 2002 reprint) project, which translates roughly as “self-design” and involves detailed instructions on how to build and customise items of furniture using simple materials, including readily-available timber, a hammer and nails. The project is composed of nineteen designs that include nine tables, three chairs, a bench, a bookshelf, a wardrobe, and four beds. The aforementioned chair, from this perspective, is part of a larger puzzle that talks of sustainability, creativity and experimentation in a world dominated by mass-produced and stylised design objects.

Design is often valued for being functional rather than beautiful; modern design is known for its minimalism and simplicity, foregrounding use over pleasure. Ornament and Crime, written by Adolf Loos in the early part of the twentieth century, declared that the time for decoration and frivolity in design was over. The new world of modern society would be efficient, productive and useful. And this, naturally, served the growing influence of industrial production – which relied on speedy mass-production of goods with fast labour and minimal materials, in order to maximize profit. As simplicity in design became prevalent, producers were able to produce more goods at lower cost and with greater profit margins. The ornamental, decorative side of design was expensive, time-consuming, and did not lend itself to either mass-production or profit-making. Beauty was out, function was in!

The functional design of autoprogettazione captures a dilemma in the history of modern design: functional design could speed up mass-production and discard the hand-made, human elements of design; but at the same time, functional design could enable a better quality of life, reducing the time and effort involved in making things, and creating objects that made life easier. And so, according to Mari, the best design objects are created by socialist thinkers working in a capitalist system. Mari puts this into practice by designing objects for mass production that circumvent the very principles of mass production.

-

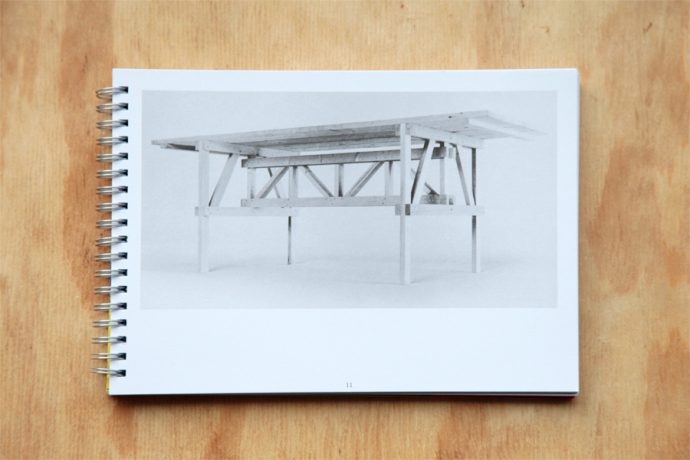

Double trouble. Long-limbed shelving from ‘autoprogettazione’. Photo by Eugenia Lim.

Mari’s socialist inclinations are evident in the autoprogettazione project. To avoid the problem of miserable factory workers slaving away at producing objects for a mass market, Mari developed DIY designs that empowered producers to create their own furniture using readily-available (and affordable!) timber and nails. The works are also customizable, so the user becomes both maker and designer. It’s tempting to see this work and think, IKEA eat your heart out! However there is an important difference between Mari’s design and the production of IKEA. While both transform the consumer into a producer, there are strict limitations involved in the IKEA iteration. We don’t get to influence the design (although we can hack it), we choose from a limited series of options, and we must go to the IKEA store to obtain the materials. Mari’s “self-design”, by contrast, enables. When we follow Mari’s guidelines, we also pick up the skills to create an infinite array of products. In this way, we become more liberated from our reliance on commercial designers and producers.

-

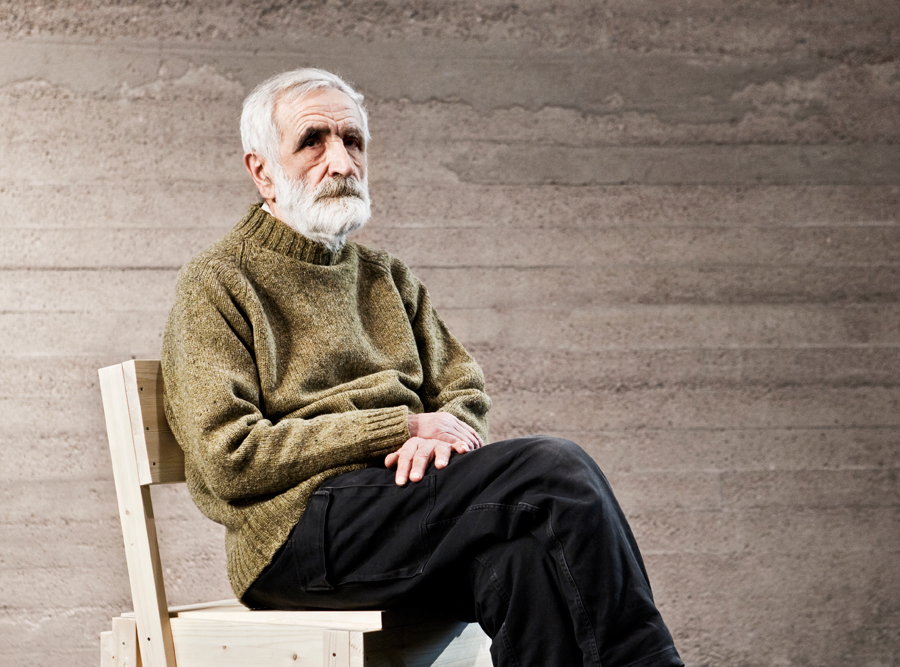

Enzo Mari constructing his famed ‘autoprogettazione’ chair. Photo courtesy twentytwentyone.com (CC-license via Flickr).

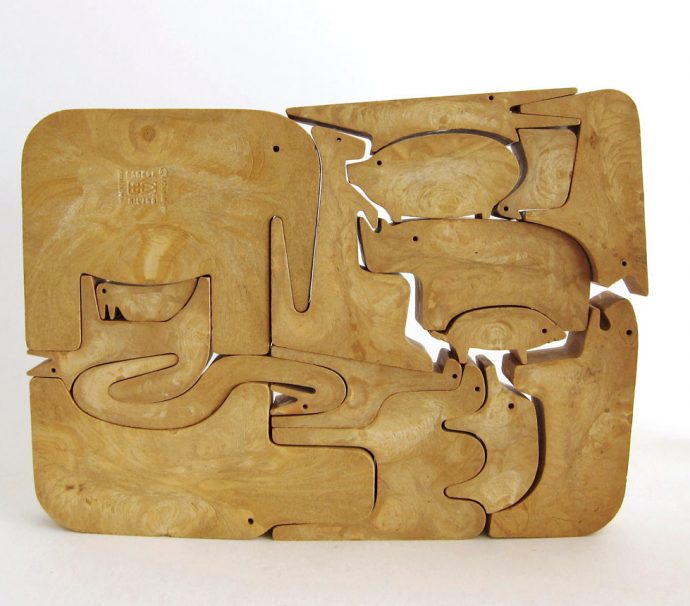

Let’s say we produce the autoprogettazione chair. We can source any materials available to us, including recycled timber or wood from our backyard – and with a nail and hammer, we build this chair. In the process, we discover we can build a different kind of chair using the same materials and steps, or indeed a table, or a bed, or a house! Mari’s design practice is puzzling because in one sense, it celebrates function and simplicity; yet at the same time, it sabotages the impetus of industrial production by privileging quality and longevity over reproduction and efficiency. It’s not surprising, following this train of thought, that some of his most celebrated work includes actual puzzles, games and children’s books – the antithesis of work and productivity. 16 Animals is a set of carved wooden animals that fit together to form a perfect rectangle and was first produced by the manufacturer Danese in the 1960s. Another minimal-waste design, the animals can be played with as individual pieces, stacked on top of each other lego-style in new constructions, or pieced together as a puzzle. Mari’s work involves pleasure and play, along with form and function; and in this sense, emphasizes the human qualities of design.

Enzo Mari’s ’16 animals’. Photo by Brett Joran (CC-license via Flickr).

-

Compact animal life. Enzo Mari’s ’16 animals’. Photo by Brett Joran (CC-license via Flickr).

Mari’s design is generous. He gifts to us the tools to create our own design environment and encourages us to experiment and play. His work is also designed to last. Not only is autoprogettazione furniture robust, practical, and sustainable – the work is also timeless in the sense that it can easily be repaired, re-built, or re-invented by the consumer. Mari has said, “I want to make objects that don’t die”. This is sustainability in its deepest sense, ideas rather than products. Mari’s design thinking has had a revival in recent years, perhaps partly due to this inherent sustainability, which has affinities with the resurgence in hand-craft and local design, especially post-GFC. Mari’s utopian aspirations, however, are deeply pragmatic; as evident in his continuing collaborations with major design brands including Danese, Driade, Zani & Zani, and Zanotta.

-

Spindly but sturdy table from ‘autoprogettazione’. Photo by Eugenia Lim.

In his collaboration with design company Alessi in 1995, Mari created a new variation of autoprogettazione, an eco-design called Ecolo that transforms household cleaning bottles into decorative vases and furniture items. Like autoprogettazione, the work includes a simple set of instructions, along with the finished product, so that customers can create their own decorative masterpieces from household detritus. In this simple idea, where an empty laundry detergent bottle transforms into an elegant table decoration, the ornamental becomes useful, and rubbish becomes beautiful. Mari confuses the relationship between function, pleasure, form and design and in this way his work is puzzling, playful and human.

You can build your own piece of autoprogettazione with the book of designs, timber, a hammer and a nail (and patience). Book stockists: Motto, the Book Depository or try ordering through World Food Books or Perimeter. As Enzo says in the book, autoprogettazione is “a project for making easy-to-assemble furniture using rough boards and nails. An elementary technique to teach anyone to look at present production with a critical eye… Anyone, apart from factories and traders, can use these designs to make them by themselves. The author hopes the idea will last into the future and asks those who build the furniture, and in particular, variations of it, to send photos to his studio at 10 piazzale Baracca, 10 – 20123 Milan”.

For more on Enzo Mari and Autoprogettazione, watch this wonderful film by Artek. Feature image (top) of Enzo Mari in his “self-design” chair is courtesy of twentytwentyone.com (CC-license via Flickr).