Alain de Botton on Living Architecture

Physical and psychological space for living, reflection and inspiration is an ongoing theme in your work. How do these interests play out in your own domestic setting – what does your own home look and feel like?

I live in a contemporary home, very uncluttered, wide, open, white. I feel I need this to counterbalance the chaos and busyness of my life. I look in architecture for values I revere but don’t have enough of in my day-to-day existence. I have always had a problem with the nostalgic side of English life, and in my house, resolutely set myself against it. It’s a house that might have been built by a Swiss architect in Zurich – it aims to suggest optimism about the future.

You published “The Architecture of Happiness” in 2006 and were named an honorary fellow by the RIBA in 2009. When did you become an architecture lover and advocate?

I grew up in Switzerland, a country with an extraordinarily high level of good, decent architecture: schools, bus stops, houses are all exemplary. It was a shock moving to the UK as a boy to see a far inferior design and construction standard – so what I’m advocating is a return to what I used to know as a child.

Overall, I believe that architecture has a huge role to play in altering our mood. When we call a chair or a house beautiful, really what we’re saying is that we like the way of life it’s suggesting to us… if it was magically turned into a person, we’d like who it was. It would be convenient if we could remain in much the same mood wherever we happened to be, in a cheap motel or a palace (think of how much money we’d save on redecorating our houses), but unfortunately we’re highly vulnerable to the coded messages that emanate from our surroundings. This helps to explain our passionate feelings towards matters of architecture and home decoration: these things help to decide who we are.

Of course, architecture can’t on its own always make us into contented people. One might say that architecture suggests a mood to us, which we may be too internally troubled to be able to take up. Its effectiveness could be compared to the weather: a fine day can substantially change our state of mind – and people may be willing to make great sacrifices to be nearer a sunny climate. Then again, under the weight of sufficient problems (romantic or professional confusions, for example), no amount of blue sky, and not even the greatest building, will be able to make us smile. Hence the difficulty of trying to raise architecture into a political priority: it has none of the unambiguous advantages of clean drinking water or a safe food supply. And yet it remains vital.

Many people view architecture either as a luxury or an ideal, something separate from their daily lives. Can you talk about the idea of accessible design and architecture in relation to your work with the Living Architecture project?

Judging from the success of interior design magazines and property shows, you might think that the UK was now as comfortable with good contemporary architecture as it is with non-native food or music. But scratch beneath the metropolitan, London-centric focus, and you quickly discover that Britain remains a country deeply in love with the old and terrified of the new. Country hotels compete to tell us how ancient they are; holiday cottages vaunt that they were already in existence when Jane Austen was a girl.

A few years ago, I wrote a book about architecture critical of British nostalgia and low expectations (The Architecture of Happiness). It got a healthy amount of attention, on the back of which I was invited to a stream of conferences about the future of architecture. But one night, returning from one such conference in Bristol, I had a dark moment of the soul. I realised that however pleasing it is to write a book about an issue one feels passionately about, the truth is that – a few exceptions aside – books don’t change anything. I realised that if I cared so much about architecture, writing was just a coward’s way out; the real challenge was to build.

So on the back of a notepad was born a project which officially launched two years ago: Living Architecture (a not-for-profit organisation that puts up houses around the UK designed by some of the world’s top architects and makes these available to the public to rent for holidays throughout the year.) We describe it as a Landmark Trust for contemporary architecture.

Our dream was to allow people to experience what it is like to live and sleep in a space designed by an outstanding architectural practice. While there are examples of great modern buildings in Britain, they tend to be in places that one passes through (airports, museums, offices), and the few modern houses that exist are almost all in private hands and cannot be visited. This seriously skews discussions of architecture. When people declare that they hate modern buildings they are on the whole speaking not from experience of homes, but from a distaste of post-war tower blocks or bland air conditioned offices.

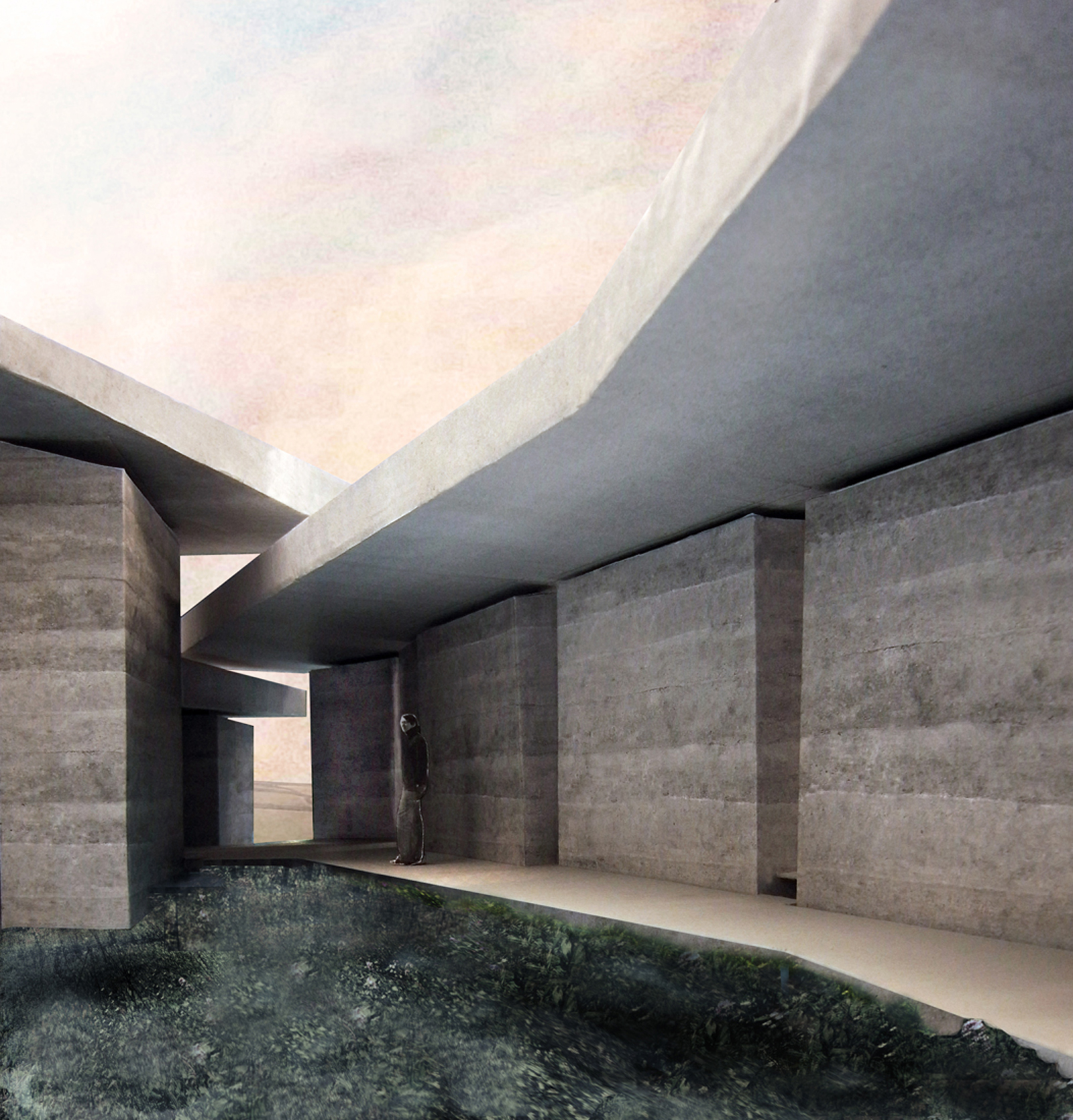

Living Architecture’s houses are deliberately varied. One of them by the Dutch firm MVRDV hangs precariously off the edge of a hill in Suffolk. Another in Thorpeness by the Norwegian architects JVA has four steel roofs, each of which houses a bedroom and a bathroom. A third, by the young Scottish practice NORD is a stark black box in the shadow of Dungeness nuclear power station. A fourth, by the legendary Swiss architect Peter Zumthor, is a secular mini-monastery which aims to bring an ecclesiastical calm and solemnity to the Devon countryside.

The idea has been to avoid the obvious and to place houses in locations one hadn’t necessarily ever thought of holidaying in and to design rooms different from those that people know from their own homes. We also want to keep things accessible. Prices start at twenty pounds per person per night and the buildings themselves, while always comfortable, are far from grand.

The organisation has an educational mission at its core, a wish to teach as well as to soothe and relax… luxurious toileteries in the bathrooms is just a way of sweetening the pill of learning. We have been criticised in some quarters for building holiday homes when there is an overall housing shortage, to which we’d simply answer that the organisation in fact hopes to lessen the demand for second homes which places such pressure on rural economies and the environment.

In the future, we hope to be able to build one new house every year – and each time, to push the boundaries of architecture a little more. We want to build a tower on the Isle of Sheppey, a house for a modern hermit in the East Anglian fenlands, a low-cost eco house outside Aberdeen and a cojoined building for a divorced family in the Yorkshire moors.

For a writer, it was undeniably something of a challenge to have to become a practical sort of person. Behind every house lies a seemingly endless procession of meetings with donors, local authorities, architects, waste disposal experts and cutlery manufacturers. The house rental business demands a keen attention to detail: you won’t get far without an in-depth knowledge of mattress protectors and the best dog policy (yes, but not in the bedrooms). Yet there’s fun in the minutiea. Whatever the pleasures of designing your own home, it’s perhaps even more satisfying imagining someone else’s holiday needs, to design their bedside library, welcome basket and closet.

I wouldn’t have driven this project forward if I didn’t believe that architecture changes our characters. We are simply not the same people in whatever room we are in. For too long in Britain, our buildings have suggested that the past is the only worthy realm, that we have to dress in the clothes of yesteryear and that technology is bad and the future terrifying. Living Architecture’s houses propose a new vision of the United Kingdom as a country that is reconciled to technology, that is no longer painfully in thrall to the past, that is democratic, tolerant, playful and optimistic.

The salvation of British housing lies in raising standards of taste. If one considers how rapidly and overwhelmingly this has been achieved in cooking, there is much to be optimistic about. Consumers have learnt to ask probing questions about salt or fat levels which it wouldn’t have occurred to a previous generation to raise. With the right guidance, a similar sensitivity could rapidly be fashioned to the worst features of domestic buildings. My hope is that a holiday in a Living Architecture house will, in a modest but determined way, help to change the debate about what sort of houses we want to live in.

What is optimism for you?

Optimism is an awareness that life is very short and therefore that the risks of trying something out are not as great as the risks of never daring.

Links

Alain de Botton: http://www.alaindebotton.com/

Living Architecture: http://www.living-architecture.co.uk/